Throughout history there have been numerous empires, none of which was built using peaceful means. All were built through the use of greater or lesser amounts of violence. During the 15th century CE, the era in which the first two great West-European transoceanic empires were first being built, there were a number of large land empires in existence on different continents: several Hindu empires in India; the Ming in China; the Ottoman and Safavid empires in West Asia; and in the Americas the Mayas, the Aztecs, the Incas, and so on. But the two European-origined transoceanic empires that emerged in the world in the 15th century CE were a new phenomenon whose creation and maintenance relied on unprecedented amounts of violence and brutality.

This was the case for a number of reasons, prime among them the following:

- Naval gunnery. The ability of the Portuguese, and soon after them the Spanish, to mount substantial cannons on ocean-going vessels and operate them with a degree of accuracy against targets on both land and sea was the fundamental game-changer in these navies’ interactions with vessels or land forces not thus equipped. Many of the naval battles fought in the early decades also included attempts to grapple, board, and take over one of the opposing ships; and in many of the early, purely naval encounters one of the main uses of cannon was to rip the opponents’ sails to shreds. Then, when the Portuguese commanders wanted to destroy the forts or settlements of Indigenes living around the African coast and then around the Indian Ocean, naval gunnery could also be used to do that. For the Spanish in and around the Caribbean, their naval cannons were not initially so vital to the success of their conquests, but their command of firearms of all sorts (including naval gunnery) certainly was.

- Hit and run capability. The ability to launch very damaging raids against land or sea targets from a distance, then execute a nearly completely safe retreat back to a friendly distant shore without being followed meant that the Catholic naval attackers could launch extremely risky (and damaging) attacks against targets on distant shores with little fear of suffering any immediate bad consequences. They could just sail away and come back another year to try again– as Afonso de Albuquerque and other Portuguese captains did on a number of occasions, against Aden and other forts around the Indian Ocean. Had commanders of land forces undertaken equally brutal and risky attacks against opposing targets, a quick and safe getaway would have been far harder to effect.

- Domination of the sea-lanes.

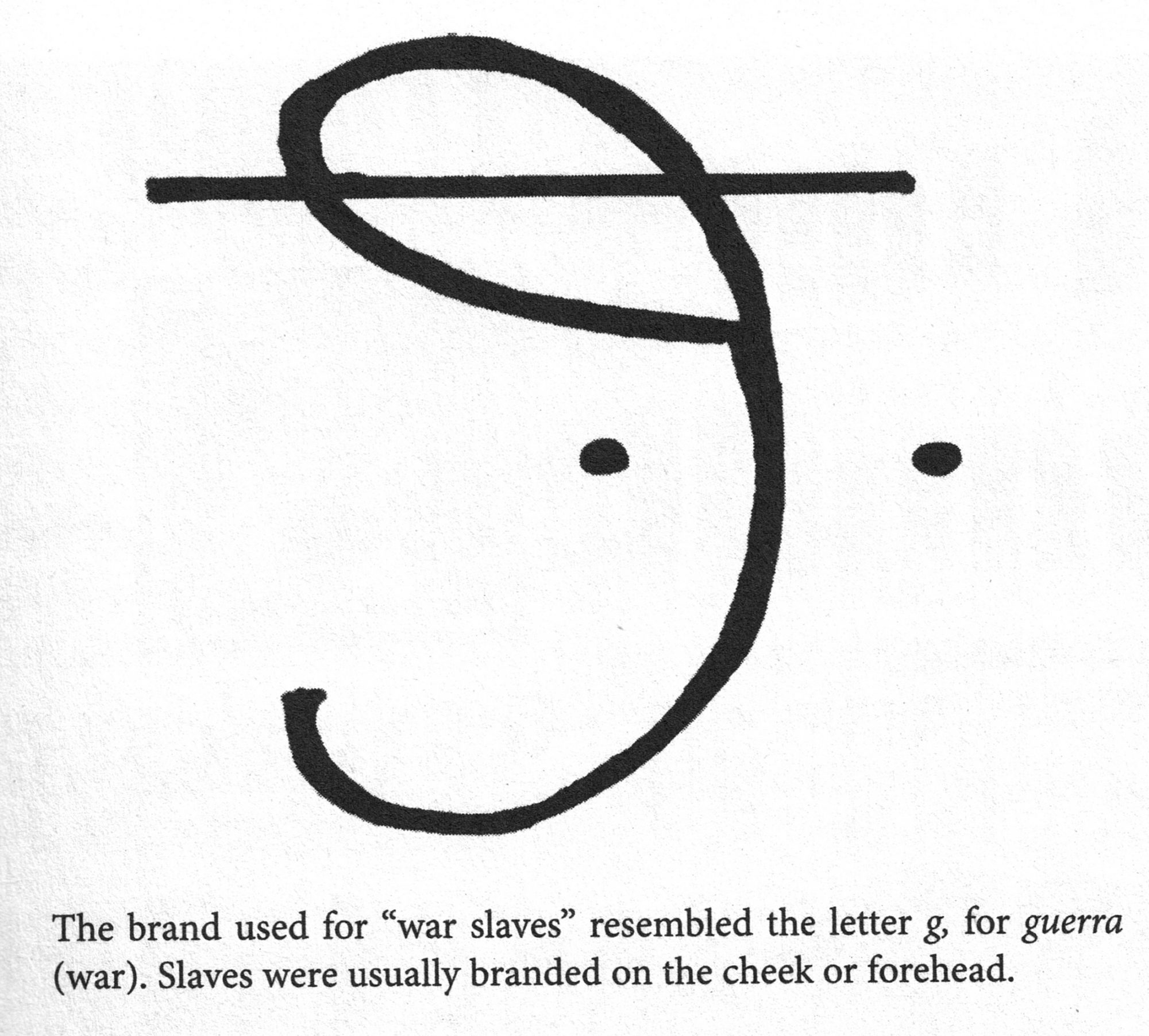

- Ability to crush any Indigenous pushback to the empire’s brutality. This phenomenon under which the West-European empire-builders could “get away with” great destruction and brutality without suffering serious consequences was of much greater applicability than “just” the context of naval attacks on the shore forts or vessels of their opponents. It also meant that, once they grabbed control of distant chunks of land, they could act there with impunity. It is no accident that the first chunks of land they grabbed were islands–whether the islands of the Atlantic grabbed by both the Portuguese and the Spanish, or the near-offshore islands of Goa and Bombay that the Portuguese grabbed in India, or the many islands the Spanish grabbed in the Caribbean. In the Atlantic islands and the Caribbean islands, the overseers of the plantations and mines the imperial powers installed there felt able to work the Indigenous populations whom they captured there literally to death; and once they had done that, they could ship in enslaved populations from very distant shores, to replace them. Or, if the local Indigenes on one island rebelled, they could be rounded up, enslaved, and shipped off to be exploited elsewhere (which happened a lot in and around the Caribbean.)

This fact of not having to face any pushback from the Indigenes–whose lands were located very far across the sea from the home ports of the empire-builders–had numerous implications for the way these new transoceanic empires could be run. In the large land empires of the time, when the empire seized control of new chunks of land, it had to find a way to integrate the residents of those lands into its governance system. Always, those means of integration would be brutal, usually involving some form of what today we would call genocide, or at the very least cultural genocide (forced conversions to the ruling religion, etc.) But the empire also “needed” to exploit the labor of these newly conquered peoples. It generally could not, as the leaders of the new transoceanic empires did, simply work them to death on a wholesale basis and then replace them with others imported to the area from a distant imperial holding.

At some level, if it wanted to be a large, stable, and growing empire, a land-based empire would have to find a way to incorporate the once-conquered people into its imperial system, using some form of indoctrination or persuasion and giving them some of their own stake in the empire’s wellbeing.

Even the rulers of the Mongol empire, which had rampaged across much of the Eurasian landmass in the 13th century CE, did this, though they are most widely remembered in the “West” for their brutality. In the end, their empire broke apart not from the actions of separatist movements of disgruntled subjects as much as from dynastic disagreements in their ruling family. So clearly, the had had some success at integrating/incorporating most of the peoples they’d conquered into their imperial project.

Another clear difference in the behavior of the new sea-based empires was that, in their distant imperial/colonial holdings, they usually did not have to worry much about the balance of power between themselves and any pre-existing, land-based empires they came up against as they grew. Their power, as exercised through the marvels of naval gunnery and their ability to effect a quick getaway allowed them to dominate, if not on their first attempt at seizing a desired shore fortification then at least on the second or third attempt.

In a subsequent stage, from the fortified outposts they built along the shorelines of Africa, the Indian Ocean, or in the Americas, on “the Spanish Main”, they could build up their ability to project power ever deeper into the interior. In some land-masses that had large, capable land-based empires like the Mughal or Ming empires in Asia, this phase could take a long time.

For the Spanish in and around the Caribbean, their possession of horses, which from early on they brought across the sea with them and which the peoples of the region had never seen before, was also a key game-changer.

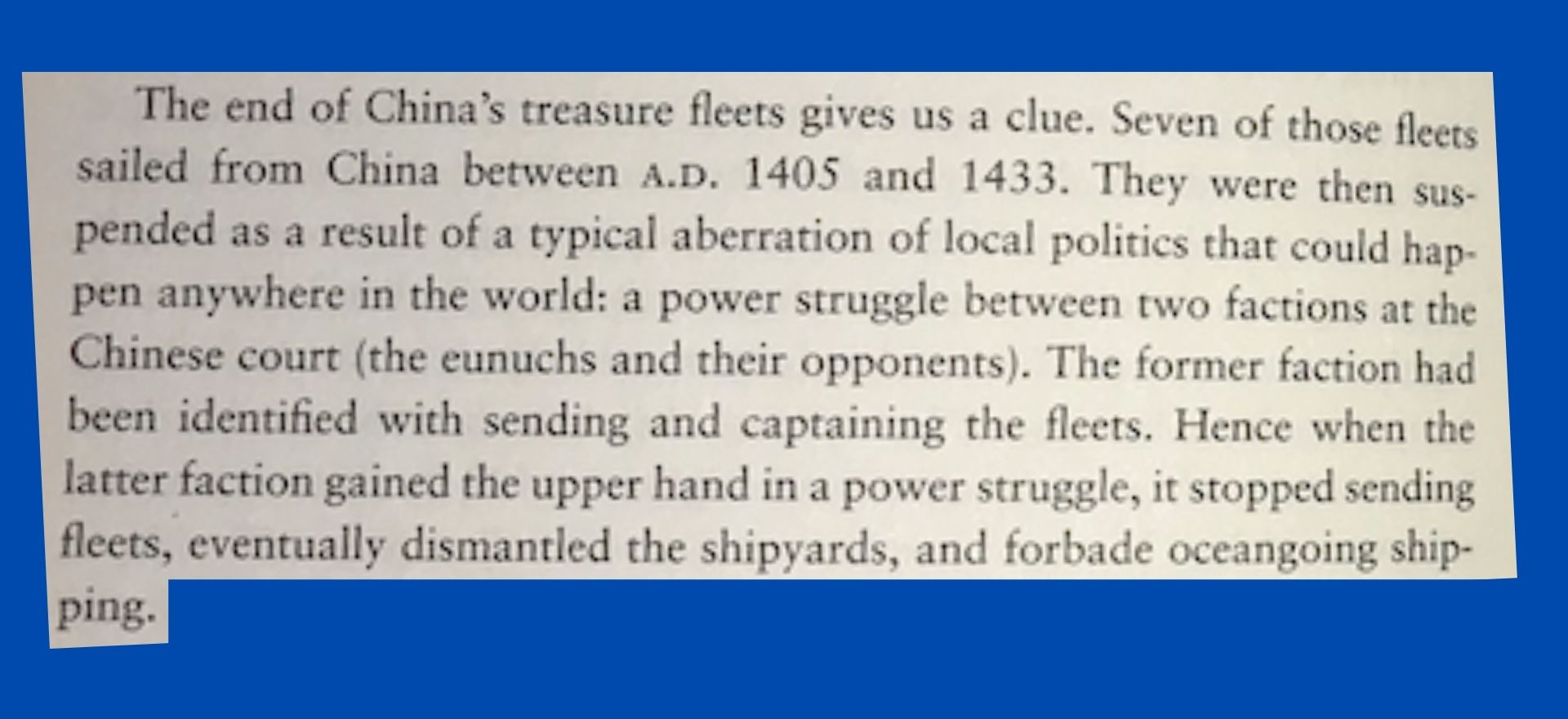

For the transoceanic conquerors, not having to worry too much about present or future pushback from the other, more Indigenous polities they came up against as they expanded made their conquests very different from those of the land-based empires. The Mongols, it is true, built their (horse-carried!) empire with amazing speed, riding roughshod over numerous pre-existing polities as they went. But as soon as their expansion paused, they found they had border issues they had to deal with. Like all the other big land-empires of that time, as throughout history, they needed always to stay attentive to the balance of power on their borders and the threat of incursions from, or alliances among, their neighbors. Indeed, for China’s Ming Empire in the 1430s, it was precisely yet another threat from the Mongols to the north that persuaded the emperor to call an abrupt end to their previous attempts to project (generally genial) sea-based power into and around the Indian Ocean while he shifted to concentrating his imperial spending on building land-forces and defenses to meet the terrestrial threat from the Mongols…

Among the “Big Five” of West European transoceanic empires that started bursting onto the world scene in the 15th century CE, Portugal, England, and Netherlands were all tiny slivers of land that–once they had launched and really committed to their (nation-unifying) imperial ventures–did not need to worry much either about control of dissidence from within their borders or about the balance of power in their home-continent. Spain and France were different. Each had large chunks of home turf they needed to worry about, and each had to stay tightly attuned to the general balance of power in their European home-continent and the threat of incursions or attacks from their neighbors.

In the case of Spain, projecting its power successfully throughout as much of Europe as possible was the primary concern of the monarchs who ruled during the 16th and 17th centuries. For them, their transoceanic empire was important nearly solely as a way of extracting enough silver and gold to be able to pay the large land armies they had in Europe. For France, the intense concerns its monarchs had with extending and maintaining power at home and dealing with their often-hostile neighbors in Europe delayed their launching of any serious venture to build a transoceanic empire by more than century. (Though the French made several half-hearted attempts to do so along the way.)

That meant that the geographically tiny polities of Portugal, England, and Netherlands had a lot more capacity for agility and focus than either Spain or France could muster, when it came to building their respective global empires. (Notable in this regard, too: Portugal, Netherlands, and England all had to overcome serious military threats from Spain as they launched their empires. All that fighting along Europe’s Atlantic coast really helped them to develop their naval gunnery…)

The Vikings and other precedents

The Portuguese and Spanish were not, as it happened, the first Europe-based polities who managed to build significant, ocean-spanning empires. From the eighth through the eleventh centuries CE, the Norse fighting seamen known generally as the Vikings burst out from their homeland in today’s Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, colonizing and raiding deep into these areas: nearly the whole Atlantic coast of Europe; most of the shores of the Baltic; deep into the Mediterranean; across the Atlantic to Iceland, Greenland and today’s Labrador; and along north-European waterways like the Volga so they could reach both the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea. (See map.)

Like the Mongols, the Vikings have also gotten a generally bad rap from the kinds of popular modern historiography that laud the supposed virtues of Western imperialism, but a little research, e.g. here, reveals that they had command of significant technologies in ship-building, navigation, metallurgy, trading, agriculture, and so on. They were also heirs to the significant corpus of Norse legends, and had developed capabilities in writing in both Latin and Runic script.

(The banner image at the top is a very much later painting of a Viking ship off the coast of Greenland.)

Like the European empires that came after them, the Vikings would often seize captives from the areas they raided, either taking those they enslaved back to their homeland or selling them to the Arab dynasties with which they did business.

I am fairly interested in the causes of the downfall of the Viking empire. (And not just because my father’s family name, which I bear, seems to have been derived from a family in the Faroe Isles named Kolbain…)

What I learned from this part of the English-WP page on the Vikings is that while various Viking hordes were doing their usual raiding-and-trading thing all around Europe and across the Atlantic, back in the homeland this was happening:

By the late 11th century, royal dynasties were legitimised by the Catholic Church (which had had little influence in Scandinavia 300 years earlier) which were asserting their power with increasing authority and ambition, with the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden taking shape. Towns appeared that functioned as secular and ecclesiastical administrative centres and market sites, and monetary economies began to emerge based on English and German models. By this time the influx of Islamic silver from the East had been absent for more than a century, and the flow of English silver had come to an end in the mid-11th century.

Christianity had taken root in Denmark and Norway with the establishment of dioceses in the 11th century, and the new religion was beginning to organise and assert itself more effectively in Sweden…

One of the primary sources of profit for the Vikings had been slave-taking from other European peoples. The medieval Church held that Christians should not own fellow Christians as slaves, so chattel slavery diminished as a practice throughout northern Europe. This took much of the economic incentive out of raiding, though sporadic slaving activity continued into the 11th century. Scandinavian predation in Christian lands around the North and Irish Seas diminished markedly.

The kings of Norway continued to assert power in parts of northern Britain and Ireland, and raids continued into the 12th century, but the military ambitions of Scandinavian rulers were now directed toward new paths. In 1107, Sigurd I of Norway sailed for the eastern Mediterranean with Norwegian crusaders to fight for the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem, and Danes and Swedes participated energetically in the Baltic Crusades of the 12th and 13th centuries…

So that is the explanation they provide there for the demise of the Vikings’ seaborne empire. Well, there were those factors, and there was also the fact that the Vikings never developed the kind of naval gunnery that would have given them a decisive advantage over the other fighting forces they encountered on land or sea… Plus, the fact that in their raiding the Vikings apparently never had the same burning kind of “God-ordained” righteousness that the later Catholic empire-builders had as their ideology, which both helped to push them to conquer distant lands “for the glory of God” and gave them far-reaching religio-ideological cover for all the brutality and sheer cruelty that the building of their empires required.

So basically, the Vikings were like the later European-origined world empires, but without the naval gunnery and without the strongly messianic sense of “Christian” justification.

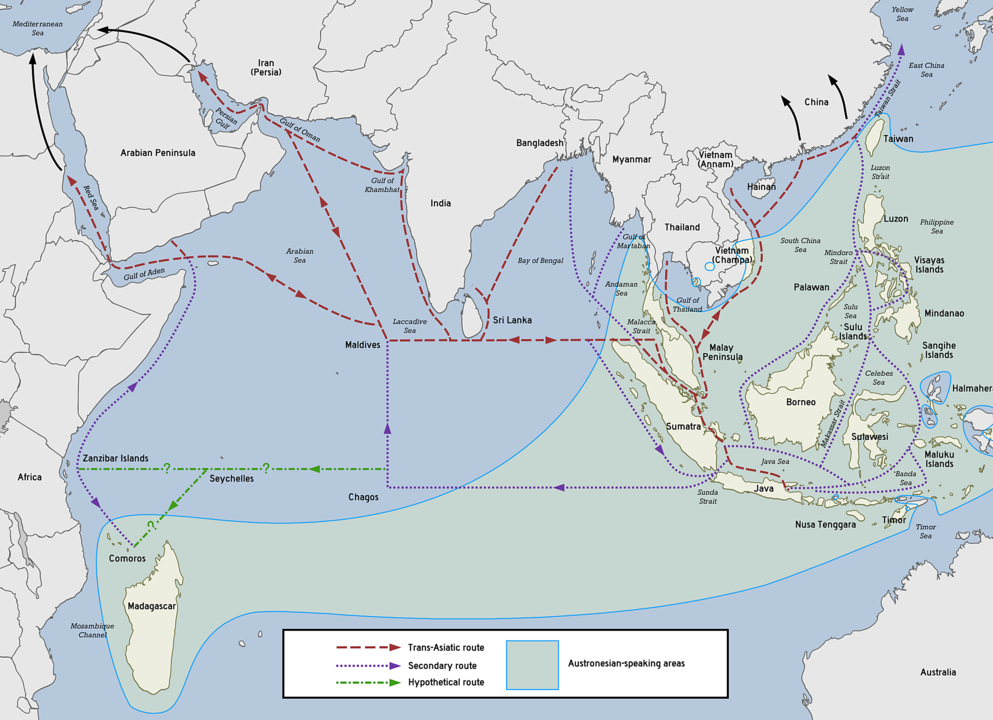

There’s another impressive sea-borne empire I’d like to note here, too. Some 2,000 years before the Portuguese reached the rich trading zones of the Indian Ocean, much of the shoreline of the ocean’s southern regions had been connected by the maritime trade networks created by the Austronesian peoples who came originally from Island Southeast Asia, sailing in catamarans and outrigger boats. The Austronesians spread their forms of language through colonization right across Southeast Asia and as far west as Madagascar.

In the map, the green areas show the spread of their language, while the various dotted and dashed lines are schematics of their trading networks.

It seems unlikely that they had any advanced forms of naval gunnery though perhaps they traveled with poisoned arrows? And did they also travel with some messianic idea that conquering other lands and the peoples in them was their destiny? I have no idea. (I have no idea, either, whether all those places that they ended up populating in the southern reaches of the Indian Ocean had previously been populated, or not. To find out… )

Jared Diamond’s silence on West-European violence and brutality

In 1997, the U.S. academic geographer Jared Diamond published a book, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies, that purported to explain how it was that West Europeans ended up creating globe-girdling empires that came to dominate all of global politics. The book, GGS, became very influential. His argument was nearly wholly based on a fairly crude form of geographical determinism. He argued that four underlying environment factors have determined the course of human history: 1) the availability of wild plants and animals for domestication, 2) the barriers to diffusion and migration within a continent, 3) the barriers to diffusion and migration between continents, and 4) population size and density.

He judged that, historically, three areas in the Eurasian land mass– but none elsewhere– enjoyed these four factors in sufficient quantity and balance for their populations to “win” in the race for global influence: the “Fertile Crescent”, Europe, and China. He then narrowed down his enquiry to ask (p.410),

Why, then, did the Fertile Crescent and China eventually lose their enormous leads of thousands of years to late-starting Europe? One can, of course, point to proximate factors behind Europe’s rise: it development of a merchant class, capitalism, and patent protection for inventions, its failure to develop absolute despots and crushing taxation, and its Greco-Judeo-Christian tradition of critical empirical inquiry. Still, for all such proximate causes one must raise the question of ultimate cause: why did these proximate factors themselves arise in Europe, rather than in China or the Fertile Crescent?

His listing of the “proximate factors” for European supremacy is notable: myopic to the point of solipsism, and more than a little ideological. The other two regions he mentioned never developed a merchant class, the conditions for continuing technological innovation or (a linked matter) for critical empirical inquiry? Really? Europe never had absolute despots or crushing taxation? Really?

He disposes of the Fertile Crescent speedily, essentially by arguing that over the centuries climate change (global warming) doomed it. I found his consideration of what happened to China’s global competitiveness more interesting. He noted (correctly) that in the medieval era, China led the world in technology (p.411). It also (p.412), “led the world in political power, navigation, and control of the seas.” He contrasted the size and heft of the fleets the Ming Dynasty sent around the Indian Ocean in the early 15th century (Zheng He’s fleets) “hundreds of ships up to 400 feet long and with total crews of up to 28,000” with the “three puny ships” with which Columbus crossed “the narrow Atlantic Ocean”. And he asked:

Why didn’t Chinese ships proceed around Africa’s southern cape westward and colonize Europe, before Vasco da Gama’s own three puny ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope eastward and launched Europe’s colonization of East Asia? Why didn’t Chinese ships cross the Pacific to colonize the Americas’ west coast? Why, in brief, did China lose its technological lead to the formerly so backward Europe?

Well, firstly, his questions there are framed in a very ideological way. Why does he assume that the Chinese would have wanted to “colonize” any distant shores that they reached, as the Europeans did, rather than just to engage in peaceful trade with the people and civilizations they encountered– which was, after all, what Zheng He’s fleet did all around the Indian Ocean?

Then, the answer he provides to his questions feels very insufficient to me:

But it was not just the “court factions” that brought Zheng He’s expeditions to an end. It was also the need to meet the Mongol threat on their northern land border.

Diamond does proceed, pp.412-16, to make some geography- and history-based arguments concerning the contrast between China and West Europe that have some merit. He notes that China has nearly always had a single predominant polity ruling over nearly all the area of the present-day PRC; it has a single system of writing, a single dominant culture, and so on. By contrast, throughout the past 500 years, West Europe has witnessed notable political disunity, with a plethora of languages and a plethora of states large and small. That environment, he argues, led to forms of intense competition among the European states that sparked innovation and a desire for exploration… and that led to the emergence of European power as dominant in a technologically changing world.

For my part, I agree that the political disunity of the West European states– especially those located on the Atlantic coast–was a very significant factor in explaining the eruption of the “Big Five” European imperialist states onto the world stage. But I think this happened not only, and not mainly, because the political fissiparity spurred innovation in many areas of technology and the humanities, as he argued, but rather, primarily, because the active and often very violent fighting amongst these five polities in Europe honed their military capabilities on land and sea and also helped push each of them into creating its own, very far-reaching transoceanic empire.

Anyway, enough of Jared Diamond. Let us just conclude that by leaving out both the essential (and often deliberately demonstrative/terrorizing) violence on which the West European were built and the strongly messianic motivations of the first two empire-building polities, he gives a very misleading account of what led to the emergence and long domination over world affairs of “the West”.

At this point, we can conclude that the first two of West European empires of the “modern” era were raiders and plunderers just like the Vikings, but with more advanced naval gunnery and a strongly messianic, Catholic-supremacist sense of motivation.

The motivation part of the next two empires to come along– the English and the Dutch–would be different. The Dutch, in particular, left evangelizing almost totally out of their imperial practices and their ideology; and both those Protestant empires helped shift the ur-justification of their imperial practices from Catholic-Christian supremacy to a broader “White” supremacy– and, as always, profit-making.

My in-depth analysis of Spain’s early decades of empire-building is in the works, and my analysis of England’s, Holland’s, and Frances will follow. (Though I already discovered and shared numerous glimpses of the emergence of these empires in the “year-per-day” blog posts covering the years 1520-1695, that I published in the first phase of Project 500 Years.) Suffice it here to note that the emergence of these five globe-girdling transoceanic empires was a new phenomenon in world history, one that the rulers of all the big land-based empires still existing in the 15th through 17th centuries had never before encountered.

Between 1520 and 1918, one by one, all those land-based empires would fall before the continued onslaught of the West-European Neo-Vikings.