In the longform essay on the birth and early decades of the Portuguese empire that I published last week, I referred to the uses the Portuguese conquistadors made of “exemplary terror” as they built their trading-forts-based global empire in the 15th and early 16th centuries CE. Any history of this empire contains numerous examples of such uses of brutality that are extremely shocking. Roger Crowley’s book, Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire focuses mainly on the efforts the Portuguese monarchs and the military/naval commanders they employed to establish strongly armed trading posts around the coats of Africa and then around the shores of the Indian Ocean. It contains many references to the use of exemplary violence. Among them, these:

1. Vasco da Gama’s incineration of the Miri, in 1502

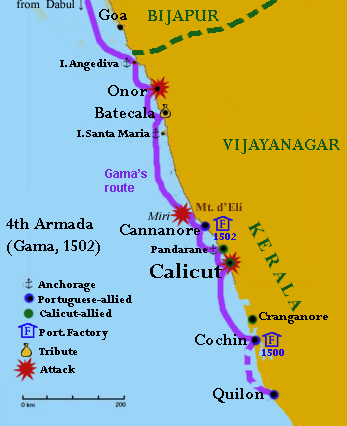

In 1502, Da Gama headed his second flotilla from Lisbon. This was also the fourth of the annual, heavily armed expeditions that Portuguese King Manuel I despatched to take the complex Atlantic Ocean route to and then around southern Africa’s tip and then into the Indian Ocean. details of this expedition are here.

Da Gama’s orders from King Manuel were to “guard the mouth of the Strait of the Red Sea, to ensure that there neither entered nor left by it the ships of the Muslims of Mecca, for it was they who had the greatest hatred for us, and who most impeded our entry into India… ” (Crowley, p.100.) As they traveled northward up the coast of East Africa, they used crude gunboat “diplomacy” to impose harsh trading terms on the Sultan of the key trading port there, Kilwa. Then, they sailed over to southwest India’s Malabar Coast where they put watchmen on top of 900-foot-high Mount Deli to look out for Muslim vessels sailing south from the Red Sea. Soon, they spied a big armed dhow coming down from the north. It was called the Miri. It was returning from the pilgrimage to Mecca and was carrying 240 men, including a number of rich merchants, as well as women and children.

Crowley tells us, p.105, that the Miri surrendered to Da Gama’s well-armed ships without a fight: “There were well-observed rules along the Malabar Coast. It had become practice to pay a toll if intercepted by pirates on certain stretches, and the merchants were well-provided, confident that they could pay their way.” The leading merchant aboard started trying to negotiate this “toll” with the new bunch of pirates who had come into this stretch of sea, and eventually agreed to extremely harsh terms, letting the Portuguese come aboard to collect. But Da Gama wanted something other than loot. Crowley, pp.106-07:

To the disbelief of the Miri‘s passengers… the ship was stripped of her rudder and tackle, then towed some distance away by longboats. Bombardiers boarded the ship, laid gunpowder, and ignited it. The Muslims were to be burned alive… For five days, the disabled Miri floated on the hot sea.

As the boat’s remaining passengers became more and more distraught, there was one final, fierce battle of hand-to-hand fighting with a Portuguese ship that was trying to board it, but eventually it sank, bearing with it all its passengers and crew except, according to some accounts, its pilot and twenty children whom Da Gama ordered to be saved and “converted” to Christianity. Crowley wrote (p.109):

The terrible, slow-motion fate of the Miri shocked and puzzled many later Portuguese commentators; by Indian historians, particularly, it has been taken as signaling the start of shipborne Western imperialism…

Along the Malabar Coast, the Miri incident was neither forgotten nor forgiven. It would be remembered for centuries: great sins cast long shadows, in the Spanish proverb. But [Da] Gama had only just started. His blood was up.

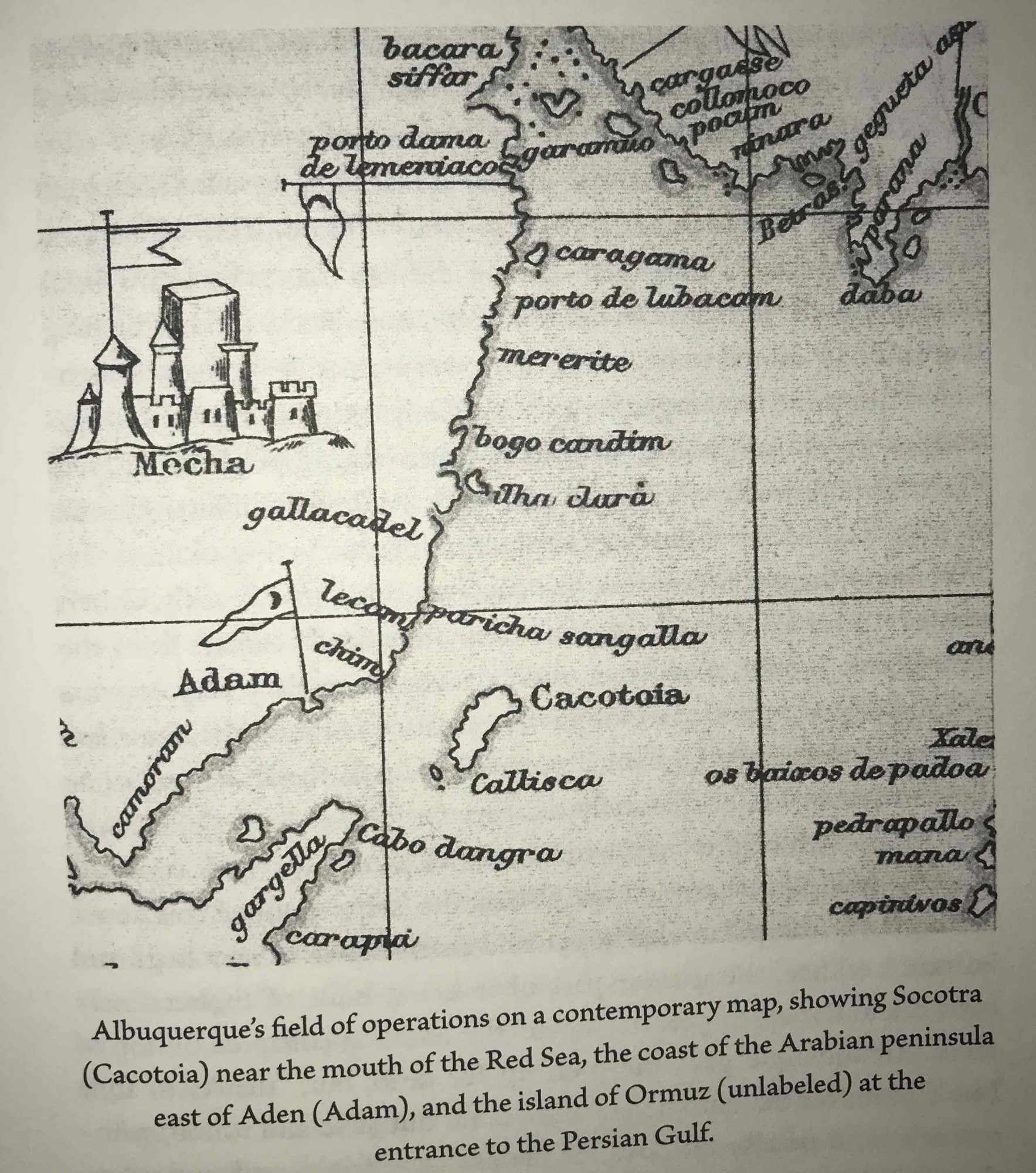

2. Albuquerque’s terror along the coasts of Yemen and Oman, in 1507

Portugal’s King Manuel was intent on continuing to try to attack the Muslim heartland in the Arabian Peninsula. But perhaps by 1506, when he sent off another armada fleet to the Indian Ocean, he had started to judge that a longer-term policy of first encircling the Muslim heartland, prior to attacking it, might be wiser. The whole notion was ambitious, to the point of foolhardiness, but he had plenty of tough, foolhardy men working for him. It took more than 10,000 miles of sailing for the fleets to get from Lisbon, around South Africa, to Arabia. It took two years for a fleet to get there and back, and thus also for reports-backs to be sent, and for new instructions to be formulated, transmitted, and received.

Anyway, Crowley tells us (p.170) that the new instructions sent with the 1506 sailing specified that this expedition should guard the mouth of the Red Sea and capture Muslim cargo ships, as before, but should also “establish treaties in places that seem useful. such as Zaila, Barbara, and Aden, also go to Ormuz, and to learn everything about these parts.”

The commander tasked with doing this was a battle-hardened old guy called Afonso de Albuquerque, who seemed clearly to exceed his instructions. Crowley tells us, p.172, how he battled his way along the Omani coast:

Some of the ports along the Omani coast submitted meekly. Others resisted and were sacked. Swarms of criminalized seamen from the Lisbon jails looted, murdered, and burned. Exemplary terror was a weapon of war, intended to soften up resistance farther down the coast. In this fashion, a strong of small ports went up in flames. In each one the mosque would be routinely destroyed; the destruction of Muscat, the trading hub of the coast… was particularly savage… Albuquerque was intent on transmitting terror ahead of him: “he ordered the ears and noses of captured Muslims to be cut off, and sent them to Ormuz as a testimony to their disgrace.”

(The banner image at the head of this post is part of a 20th-century mural of Afonso de Albuquerque by Jaime Martins Barata, located at a “Palace of Justice” in Lisbon.)

3. Albuquerque’s sack of Goa in 1510

Crowley has entire chapter, Chapter 19, titled “The Uses of Terror.” Its key focus is Albuquerque’s 1510 capture of Goa, the key West-India trading hub that would serve as Portugal’s headquarters on the subcontinent from then until 1961. At p.252, Crowley includes the following translation of the report that Albuquerque sent back to King Manuel about this:

I have burned the town and killed everyone. For four days without any pause our men have slaughtered… wherever we have been able to get into we haven’t spared the life of a single Muslim. We have herded them into mosques and set them on fire. I have ordered that neither the [Hindu] peasants nor the Brahmans should be killed. We have estimated the number of dead Muslim men and women at six thousand. It was, sire, a very fine deed.