I’m at the transition point between completing the big essay on the birth of the Portuguese empire, which I published August 30, and sitting down to plan the next essay in the “Big Western Imperialisms” series, the one on Spain. Astute readers of the Portugal essay will have found some references there to the Portuguese royals’ continuing competition with (and frequent antagonism to) the monarchs of Castile, which was the originating home polity of what would become the Spanish Empire–along with mentions of two moments in the founding of the Spanish Empire, and also of Castile/Spain’s abrupt takeover of Portugal in 1580. So clearly, the birth stories of these two empires overlap/interact in some very interesting ways…

However, this overlap of the two empires also gives me the chance to do some deeper exploration of two key aspects of this pair of “foundational” Western imperialisms, namely:

- the ways in which the establishment of each of these empires interacted with the emergence and consolidation of distinct languages for each of them; and

- the associated interaction, in each of these two cases (and also, of the three European imperialist states that will follow them), between the venture of empire and the consolidation of nation-state formation in their own respective metropoles.

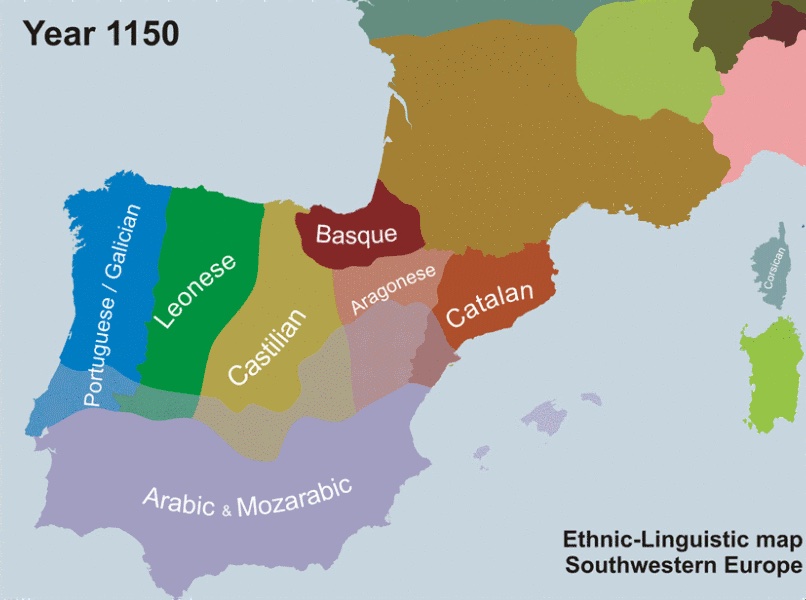

Definitely of note here: the fact that prior to Portugal and Castile/Spain launching their respective empire-building projects, their home peninsula in southwest Europe was home to seven linguistic communities, six of them communicating in a variety of post-Latin “Romance” language and the other one using the very different Basque language, as indicated in the map here. (You can see a great schematic GIF of the changes the peninsula’s language groups underwent between 1000 and 2000 CE, here.)

It was only after, or simultaneously with, the launching by Portugal and later Castile/Spain of their respective imperial projects that each of these two groups’ languages became solidified into a language of empire and of state. Much more on this, below…

Nationhood, language, and Benedict Anderson

For my part, growing up and being educated in England, I emerged with a fairly strong sense of “Englishness” as something essential and largely unchanging whose origins were shrouded in the mists of ancient time–somewhere between “King Arthur burning the cakes” and the amazing creations of William Shakespeare. And as a corollary to that, that along the way that “plucky” and pre-existing English nation had built itself an empire; but definitely, that the nation was antecedent to empire. Of course, I also read and to a certain extent internalized all the Marxist teachings about the essential human group being not nation but class, and the concept that modern-day nation-states were the creature of the national bourgeoisie.

It was, sadly, not until much later that I read Benedict Anderson’s powerful work Imagined Communities, in which he made a much stronger argument against the idea that nationhood is some “essential” aspect of human existence. “Nations”, he argued, had emerged as the product of collective acts of creativity that he dubbed “imagining”; and he posited that some of these proto-nations had become consolidated into nations–most of which had states associated with them–through the operations, mainly, of “print capitalism.”

Much of the fieldwork on which Anderson was basing his conclusions came, as I recall it, from Thailand; and his argument was fascinating and thought-provoking. (I’ve put a hold on Imagined Communities at my local library, so I can re-read it.) However, if we look at the operations of print capitalism as leading to the emergence of nations and their states–or, of states and their nations, which is the way I’m inclined to view things–then the history of nation-state formation in Europe itself really does not indicate that.

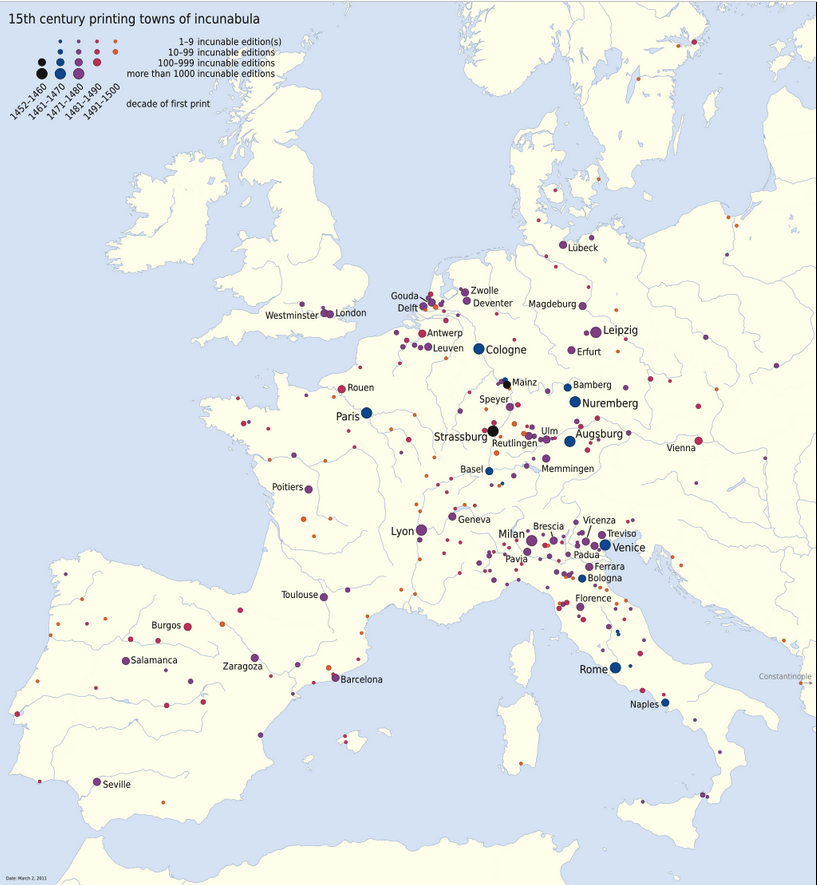

For example, look at this map (click on it to expand) that shows all the towns in Europe in which printing was done prior to 1500 CE.

(European materials printed before 1500 CE are known as “incunabula”. See a definition here. It includes books, pamphlets, and broadsheets printed either from hand-carved woodblocks or, with increasing frequency, from set-ups using movable type. Movable type was developed and first used in Europe by Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany, between 1436 and 1450 CE. It had been used in China as far back as 1040. Fwiw.)

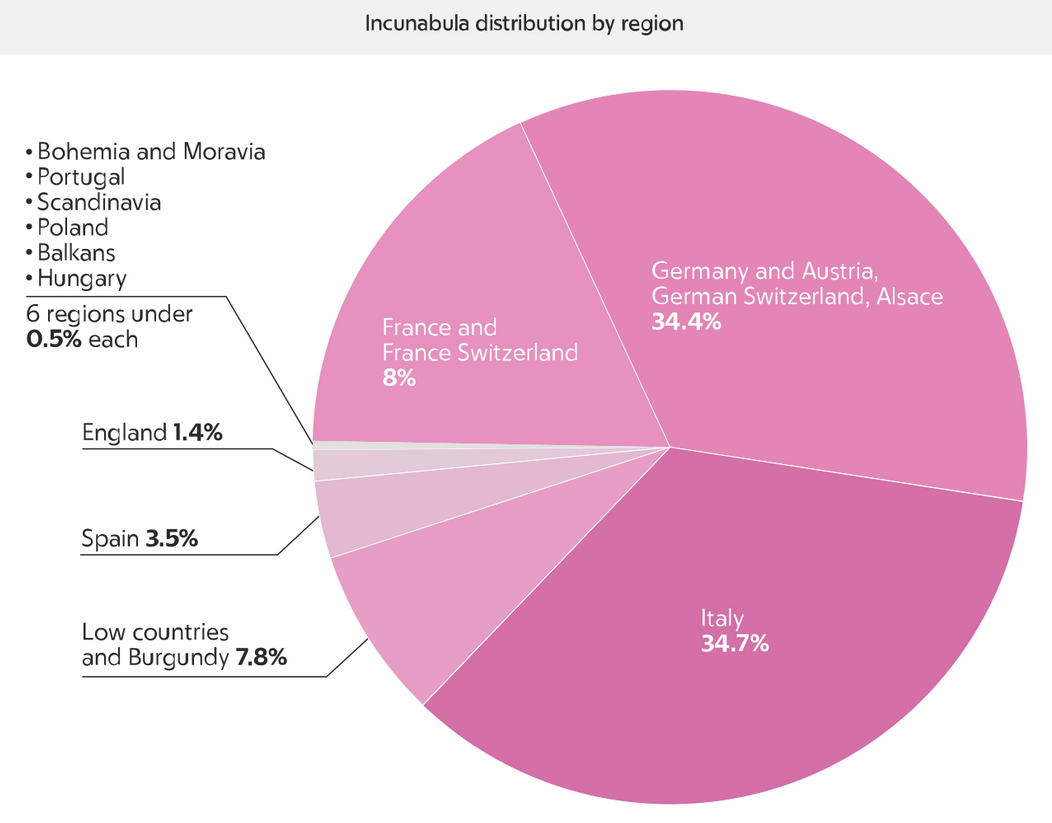

Anyway, a glance at that blue-and-yellow map shows that the greatest amount of printing in Europe prior to 1500 was done in northern Italy, Germany, and the Low Countries. (See, too, the pie-chart at right, from this WP page on Incunabula.) But Italy and Germany didn’t become nation-states until very, very much later… whereas for Portugal and Castile/Spain, you can say that by 1500 they were clearly either emerging or well-established as nation-states–and neither had any significant network of printshops, at all. The key variable in the development of those nation-states was not, it seems to me, the development of “print capitalism”, but rather, the development of transoceanic empires.

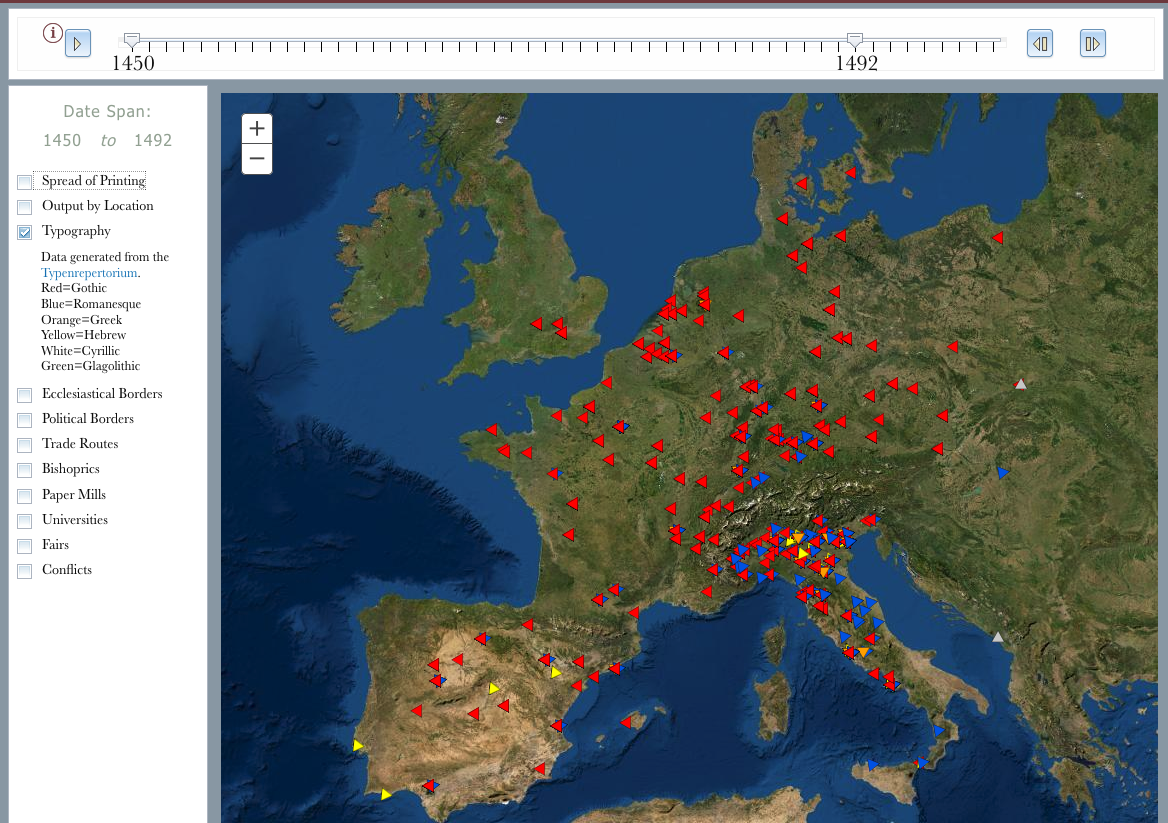

I also visited this intriguing website on the early development of printing tech in Europe, where I clicked on the tab “The Map” and learned about the typographies being used in these various European centers of printing in the 15th century. Using the slightly clunky slider at the top I got this image of all the printshops opened in Europe between 1450 and 1492:

The locations of those printing centers are the same as shown in the earlier map. But in this map, note the color-coding: a yellow triangle signifies a Hebrew-letter printshop; a red one that it used Gothic typefaces; and a blue one that it used a typeface in some Romanesque typeface. Thus in all of Portugal, in 1492, there were two Hebrew-type printshops and none in any other orthography. In Spain, there were several Gothic printshops, four “Romanesque” (in Seville, Salamanca, Burgos, Zaragoza), and a couple of Hebrew ones.

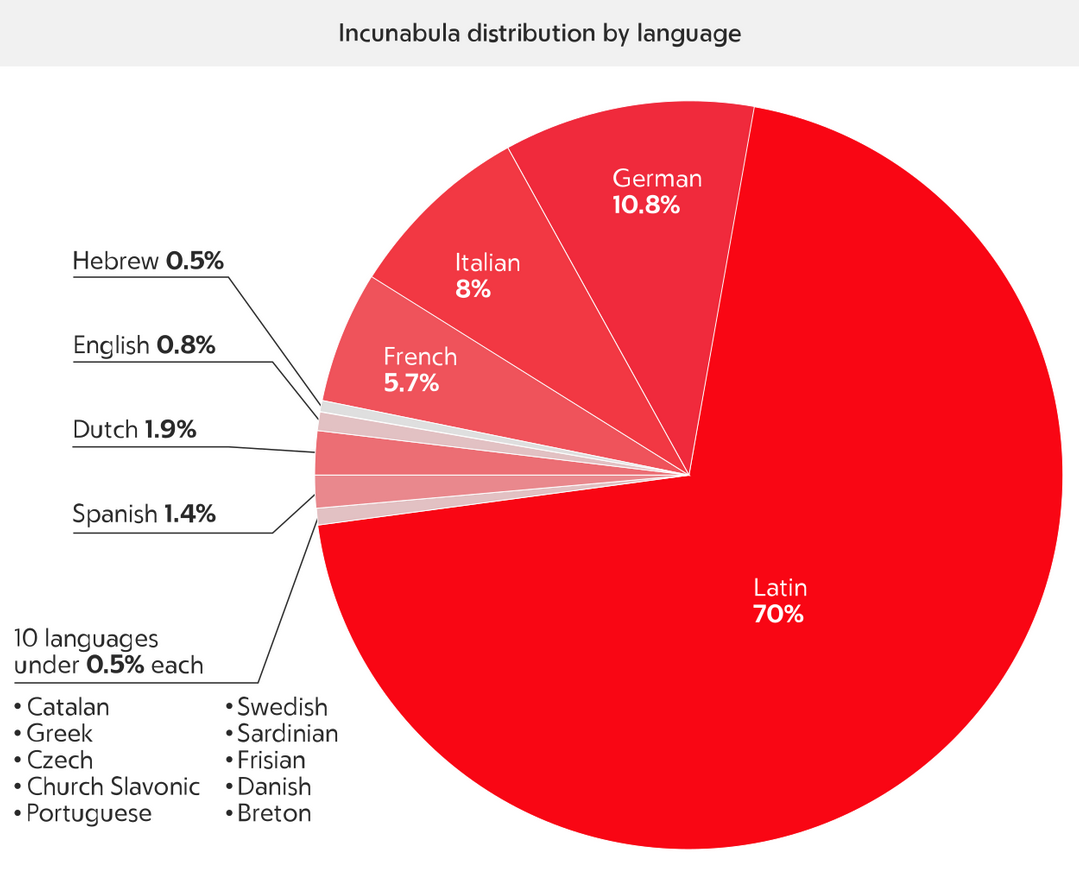

My understanding is that in that era much of the printing that the royals, the merchants, and others in Portugal wanted to have done, they commissioned from printers in Antwerp. By 1494, Portugal had acquired its first printshop that used a Romance language. But still, the vast majority of the output of the European printshops that were using a “Romance” language was still in Latin, as shown in the red pie-chart.

Language and empire-formation in Spain

1492 saw three major events in Castilian/Spanish history:

- the “Catholic Monarchs”, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, took control of Granada, ending (through a negotiated surrender) the last outpost of Muslim rule in Iberia;

- they gave the Genoese adventurer Christopher Columbus a commission to take a small fleet to find a new sailing route westward get to “the Indies”, and he encountered the land-mass that later became known as “the Americas”, instead; and

- a savant from the area of Seville called Antonio de Nebrija published the first ever book-length guide to the grammar of the Castilian language. He dedicated the book to Queen Isabella in a prologue that stated: “I have found one conclusion to be very true, that language always accompanies empire, both have commenced, grown and flourished together.”

Nebrija’s grammar book was immensely influential. It was the first systematic attempt to codify one of the post-Latin vernacular languages. (Prior to publishing it, he had already published an influential primer of Latin grammar.)

As we know, Castilian, whose structure had been so robustly codified by Nebrija, became the language of the Spanish state, leaving in the dust Ferdinand’s Aragonese and all the other dialects/languages that in 1400 had been used in the area that became modern “Spain”. Of those other languages, only Catalan retained any resilience. (I recently sold the Catalan-language rights to one of the books I’ve published– separately from the Castilian-Spanish rights.) Basque lives on in some form; and Galician long ago morphed into or was otherwise subsumed by Portuguese (see below.)

To a great extent, then, we can see that Nebrija’s publication of his Gramatica de la lengua castellana, along with his dedication of it to Queen Isabella and its printing and apparently wide distribution throughout Castile, played a crucial role in solidifying the idea and the incipient nationhood of “Castilian-ness” (which later morphed into “Spanish-ness”), including through its privileging of Castilian language and culture within that nation.

But Nebrija’s ambitions were much wider than merely the Castilian/Spanish nation. As Henry Kamen noted in his 2002 book Empire: How Spain Became a World Power, 1492-1763 (p.3), when Nebrija presented the book to Isabella, at first she didn’t understand its purpose. After all, everyone in her entourage already knew how to communicate in Castilian, so why should they need such a book? As Kamen records it, her confessor the Bishop of Avila stepped in to explain: “After your highness has subjected barbarous peoples and nations of various tongues, with conquest will come the need for them to accept the laws that the conqueror imposes on the conquered, and among them will be our language.” Kamen notes that Isabella was already familiar with that idea, since her armies had already conquered so much of Iberia from the Muslims.

Nebrija then incorporated the bishop’s argument into his prologue, as noted above.

So what Nebrija was “imagining” into existence there was not just the Spanish nation, but also the Spanish empire. That very same year, Columbus returned from his first voyage and it became clear that this empire would stretch not only far across Europe (which it soon would, through a combination of dynastic marrying and armed conquest), but also across the Atlantic Ocean to very distant shores.

The development & solidification of Portuguese

Portuguese, like Castilian, had started out as a vernacular dialect of the Latin language that Roman soldiers, settlers, and merchants had brought to the peninsula starting in around 200 BCE. Those vernaculars had more or less survived the intrusion of Visigoths and other peoples who poured in the area as Roman rule collapsed. In the 8th century CE, as I described earlier, Muslim armies came in from North Africa. For the next 700 years, most of the elites in the Muslim-ruled parts of the peninsula communicated in Arabic; the non-elite residents continued to communicate in one or more versions of vulgar Latin, which collectively became known as Mozarabic. (When Mozarabic was written down, it was generally written in Arabic script, though sometimes in Latin or Hebrew script.)

Meantime, residents of the northern portions of the peninsula continued to speak their varieties of vulgar Latin, one of which originated in the northwest area of Galicia and became known as Galician-Portuguese, or Portuguese-Galician. Here at right is the 1150 CE still from the GIF of language changes in south-west Europe.

Then, as the dukes/kings of the area of Porto, known as the Portuguese, continued to push southward against the Muslim rulers, they took their language with them. In 1249, the Portuguese finally captured the remainder of southwest Iberia (known as the Algarve) from the Muslims, completing the “Re”-conquista of the lands they claimed. In 1290, King Denis founded a center of higher learning in Lisbon, which later moved to the city of Coimbra. The language of instruction there was reportedly, from the beginning, Portuguese rather than Latin. Crucially, in that same year, Denis also decreed that Portuguese should be “the official language of legal and judicial proceedings” throughout his kingdom.

From 1415 on, as the kings of Portugal and those around them were pursuing their large empire-building project that went down the west coast of Africa and around Africa into the Indian Ocean, Portuguese was the common language used by all involved in the project.

This page on WP tells us that,

By the mid-16th century, Portuguese had become a lingua franca in Asia and Africa, used not only for colonial administration and trade but also for communication between local officials and Europeans of all nationalities. The Portuguese expanded across South America, across Africa to the Pacific Ocean, taking their language with them.

Its spread was helped by mixed marriages between Portuguese and local people and by its association with Roman Catholic missionary efforts, which led to the formation of creole languages such as that called Kristang in many parts of Asia (from the word cristão, “Christian”). The language continued to be popular in parts of Asia until the 19th century. Some Portuguese-speaking Christian communities in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Indonesia preserved their language even after they were isolated from Portugal.

Today, by the way, by far the largest group of Portuguese speakers anywhere in the world is the citizenry of Brazil, who are about 20 times as numerous as the population of Portugal. (And the spoken forms of these two dialects of the language have diverged considerably. See this helpful short video about that.)

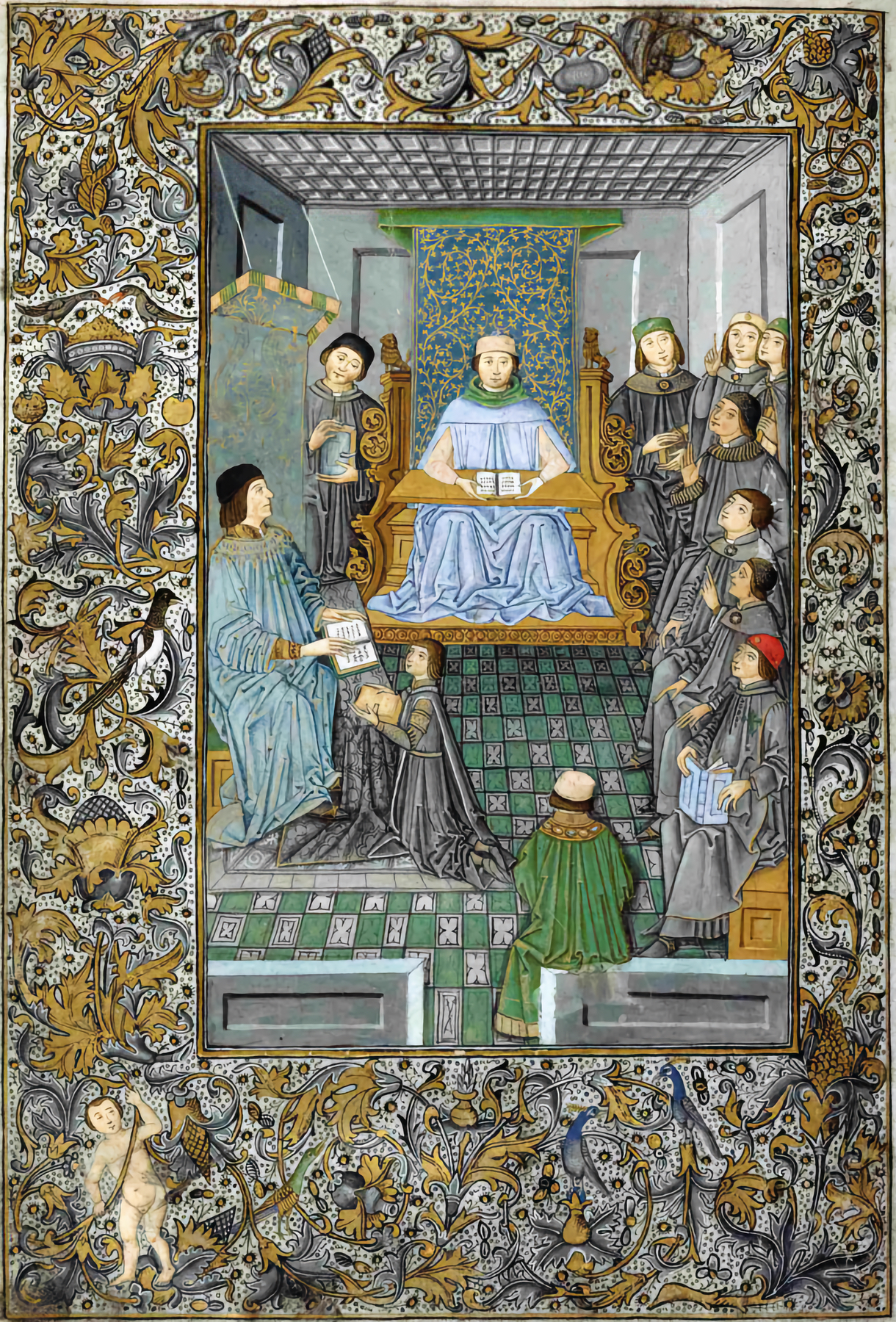

But back to language and its role in helping to form a sense of Portuguese nationhood. It seems clear that the use of Portuguese in all aspects of the venture of empire antedated the emergence of any really significant literary production in the language by many decades. In 1536, Fernão de Oliveira (1507 – c.1581), described as a “grammarian, Dominican friar, historian, cartographer, naval pilot, and theorist on naval warfare and shipbuilding,” published the first grammar of the Portuguese language, the Grammatica da lingoagem portuguesa. Four years later, João de Barros, a builder and chronicler of the Portuguese empire, followed suit, publishing a Gramática da Língua Portuguesa, which also contained some instructive moral dialogues “to help to teach young aristocrats”, and some woodcut illustrations.

De Barros’s biography was also interesting. In 1524, at age 28,he was awarded the”captaincy” of the fort at Elmina, in today’s Ghana,which was already well developed as a hub for the collection and out-shipment of enslaved Africans by Portugal’s monarchy-backed Casa de Guiné e Mina. A year later, King John III appointed him treasurer of the Casa da India. Later in the 1530s, after John had divided the land of Brazil into “captaincies” designed to boost the establishment of settler colonialism there, De Barros was given the northern captaincy of Maranhão… but the armed fleet of ten vessels that he and two partners sent out to launch their colonial venture there was shipwrecked en route.

It seems to have been right after that failure that he composed and published his Gramática. He also went on to write a multi-volume history of the Portuguese in Asia.

It thus seems clear that the codification, development, and systematic teaching of the Portuguese language was, as in Spain, intimately connected with the venture of empire-building. For Portuguese, however, this codification came at a much later stage in the empire-building process than in Spain. For Portuguese, it came many decades after the language had already been in common use as a lingua franca for traders all around Africa and the Indian Ocean, as well as in the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

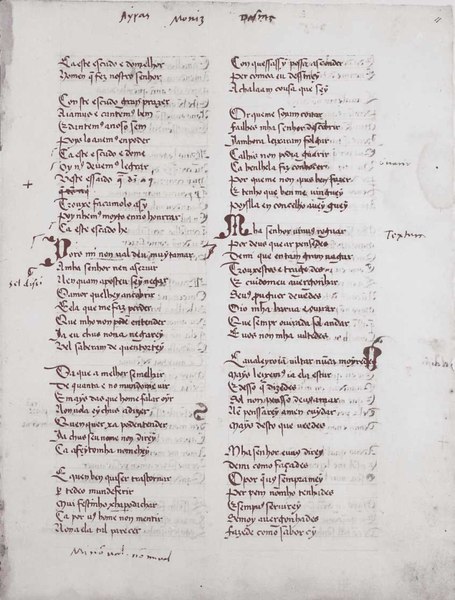

But what of literature, meanwhile? Portuguese had, it seems, often been the language used in lyric poetry throughout much of Iberia, including Castile. But it was not until 1572 that Portuguese speakers saw published a substantial work of literature in their own language. This was Os Lusíadas, usually translated as The Lusiads, an epic poem written by Luís Vaz de Camões (c. 1524/5 – 1580), which according to Wikipedia is still “widely regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature.”

In The Lusiads, Camões tells the story of Vasco da Gama’s trans-oceanic expeditions in a quasi-Homeric fashion that seems to mix up the record of Da Gama’s very well-funded voyages of plunder and imperial expansion with Ulysses’s much more desperate attempt to return to his home and hearth.

English Wikipedia tells us this:

The heroes of the epic are the Lusiads (Lusíadas), the sons of Lusus—in other words, the Portuguese. The initial strophes [stanzas] of Jupiter’s speech in the Concílio dos Deuses Olímpicos (Council of the Olympian Gods), which open the narrative part, highlight the laudatory orientation of the author.

In these strophes, Camões speaks of Viriatus and Quintus Sertorius [two historic figures who had risen up against Roman rule in Iberia], the people of Lusus, a people predestined by the Fates to accomplish great deeds. Jupiter says that their history proves it because, having emerged victorious against the Moors and Castilians, this tiny nation has gone on to discover new worlds and impose its law in the concert of the nations. At the end of the poem, on the Island of Love, the fictional finale to the glorious tour of Portuguese history, Camões writes that the fear once expressed by Bacchus has been confirmed: that the Portuguese would become gods.

Camões, by the way, had been blinded in one eye as a young man. Like the grammarians De Olivera and De Barros, he had spent substantial amounts of time in the Asian portions of the Portuguese Empire before he wrote his book. But his record there seemed much more colorful (spotty?) and less well-favored than that of De Barros. He was born to a family of minor nobles and seems to have traveled to the Indian Ocean in a spirit of adventure. He spent various amounts of time in Portuguese jails in Malacca, Goa, and Mozambique. But after many adventures he managed to return to Portugal, where he recited his epic poem to the young King Sebastian in 1570 or 1571. Sebastian ordered the work to be printed and published, which happened in 1572.

(The banner image at the top of this page is part of another portrait of Camões, painted in 1581 in Goa.)

Five years after Sebastian published Camões’s epic he was, as I wrote here, the young king who led a very ill-planned military adventure to Morocco that in 1580 brought about the end of the dynasty of which he’d been part and the takeover of all of Portugal (and its empire) by the country’s long-time competitors in Spain…

But in 1572, that “fate” still lay ahead. After he published The Lusiads, Sebastian granted Camões a pension that allowed him to live in a modicum of comfort–attended by an enslaved person he had brought with him “from the east”; and he died in 1580.

As for the fate of Portugal, its empire, and its language… clearly, many or most people in the area of Portugal retained some sense of “Portuguese-ness” as distinct from the Spanish/Castilian identity because 60 years later, the Portuguese Cortes (a sort of nobles’ parliament) convened a special meeting, anointed a new King, and proclaimed and successfully implemented the country’s independence from Spain.

This continuing sense of “Portuguese-ness” and Portuguese distinctiveness from Spain was probably fostered by at least these factors:

- Even after the Spanish takeover, Portugal continued to be ruled by its own “Council”, in the Spanish system of having separate “Councils” for Castile, Aragon, and other other sub-areas, with the Council of Portugal only loosely supervised from Madrid.

- This Council of Portugal continued to use Portuguese as its administrative language; and the language continued to flourish in the post-Lusiads era.

- Most members of the Portuguese elite continued to have pride in — and derive profits from — the imperial projects that, in the Lusiads had been portrayed as a key determinant of national meaning. But they had a strong sense of grievance that in the period of Spanish suzerainty, Madrid had not invested nearly enough to keep those Portuguese projects viable and profitable, instead favoring Spain’s own imperial projects.

The role of “print capitalism”?

As noted above, I don’t have a copy of Benedict Anderson’s book to hand right now. But my recollection of his argument is that it was “print capitalism”–that is, roughly speaking, a network of capitalism-powered institutions for the composition and curation of texts and other printed materials, the printing of those (primarily textual?) materials, and then their marketing and distribution–that helped to solidify people’s affiliation with one particular national group, defined in terms of its language and culture, and their loyalty to the state associated with that nation.

I have just found a very relevant quote of his (Ch.3):

in their origins, the fixing of print-languages and the differentiation of status between them were largely unselfconscious processes resulting from the explosive interaction between capitalism, technology and human linguistic diversity.

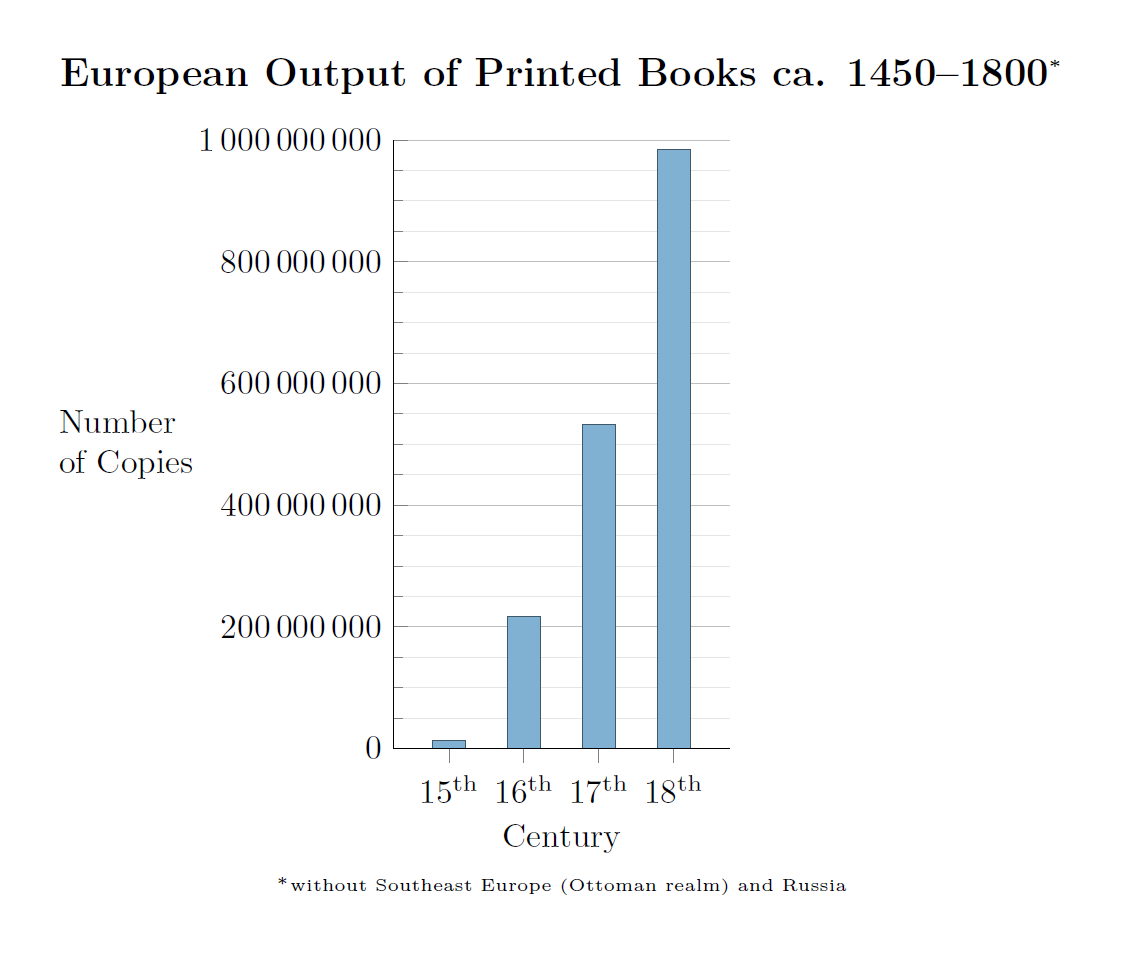

Now, it is absolutely true that, as shown in the graph at right (source, here), the era of the emergence of nation-states in Europe coincided with an explosion in the number of print books produced in the continent. But two of the earliest nation-states to emerge in Europe were Portugal and Spain; and as we saw above the development and codification of those countries’ respective (but originally, pretty similar) languages occurred under the strong influence of their monarchs and of the imperial projects originated and supported by those monarchs. Any influence that capitalist-run, free-market printing and publishing ventures may have had seems almost certainly to have been very small.

So honestly, regarding the “fixing” of the print-languages of Portuguese and Spanish, I would say that Anderson was wrong on all counts. The fixing of these two (originally very similar) languages and the differentiation between them were not “largely unselfconscious”, but were in both cases very intentional. And in neither case did the fixing of the language result from any interaction (whether explosive or not) “between capitalism, technology and human linguistic diversity.” Instead, in the case of Portuguese it resulted from (1) the early decision that King Denis took, shortly before Portugal’s completion of its Reconquista of south-western Iberia, to have the language of instruction at his inaugural university and the language of his administration both be Portuguese, rather than Latin (which presumably also required the production of many hand-copied written materials?); then (2) the growing need for one oral lingua franca through which all the far-flung participants in Portugal’s royal-backed empire-building projects could communicate; and (3) the need for a single written language in which the communications between those far-flung outposts of empire could be conducted and recorded; and finally (4) the commitment that two significant figures in that imperial project made, in 1536 and 1540, to codify their language through the composition/compilation of formal grammar books.

In the case of Castilian/Spanish, we could say that that language was fixed at the time of Nebrija’s 1492 (and royal-backed) production of his grammar of the Castilian language. But Nebrija, his backer the Bishop of Seville, and eventually Queen Isabella herself all presumably saw the value of his project in light of what they already knew about the reliance of their neighbor/competitor Portugal on a single, widely understood and widely used lingua franca as its leaders conducted the affairs of their global empire.

Of significance, too: that Isabella and the Bishop did not choose simply to adopt Portuguese as their lingua franca— though it was widely used in all the trading networks along Europe’s Atlantic coast, was widely understood in Castile at the time, and indeed admired there as the language of some much-appreciated courtly poetry. Instead, by backing the publication of Nebrija’s work, they sought to harden the differentiation between the written-and-codified language of their empire and that of the Portuguese.

In both these cases, the fixing of the language was done under the auspices of the monarchy, not under the influence of capitalism; and in both cases (though in different ways) the fixing was done under the strong influence of the respective monarchies’ crucial empire-building projects.

The Catholic church, Latin, and the post-Latin languages

I cannot end this essay on the role of language solidification/codification in these first two West European empires/states without noting the continuing role of Latin as the liturgical language of the Catholic church and the administrative language of the Vatican and the rest of the church bureaucracy. (Later, when I consider the emergence of the next two of the West European empires/states, England and Netherlands, which were specifically non- or anti-Catholic polities headquartered in areas where the existing vernaculars were not post-Latin languages, the church-related aspects of the “national language” question will be thrown into into even sharper relief.)

Until 1290, the language used for administrative purposes throughout all of western Europe was the form of the ancient-Roman language of Latin that was kept alive through the practices of the Catholic church. The decision that Portugal’s King Denis took that year to inaugurate the use of Portugal’s “vulgar” derivative from Latin as his kingdom’s administrative language marked a clear departure. According to Denis’s page on Wikipedia, this step was part of a bundle of administrative reforms that also involved:

ridding the [Catholic] military orders in the country of foreign influences. His policies encouraged economic development with the creation of numerous towns and trade fairs. He advanced the interests of the Portuguese merchants, and set up by mutual agreement a fund called the Bolsa de Comércio, the first documented form of marine insurance in Europe, approved on 10 May 1293. Always concerned with development of the country’s infrastructure, he encouraged [mining and export ventures]

Denis signed the first Portuguese commercial agreement with England in 1308, and secured a contract in 1317 for the services of the Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Portuguese form of the Italian “Pezagno”) as hereditary admiral of his fleet… thus effectively founding the Portuguese navy.

King Denis came to the throne at age 18 and ruled for 46 years. Reining in the foreign influences exerted through the military orders was not the only step he took to curb the still-huge power of the Vatican. We learn here that,

In 1284… Denis emulated the example of his grandfather and father, and launched a new series of inquiries to investigate the expropriation of royal property; this was to the detriment of the church. The next year he took further steps against ecclesiastical power when he promulgated amortisation laws. These prohibited the church and religious orders from buying lands, and required that they sell or forfeit any they had purchased since the start of his reign. Several years later he issued another decree forbidding them to inherit the estates of recruits to the orders.

In 1288, Denis managed to persuade Pope Nicholas IV to issue a papal Bull that separated the Order of Santiago in Portugal from that in Castile, to which it had been subordinate. With the extinction of the Knights Templar, he was able to transfer their assets in the country to the Order of Christ, specially created for this purpose.

(130 years later the nicely funded, and very Portuguese, “Order of Christ” would be the major vehicle through which King John I and his son Henry the Navigator would finance and organize those proto-imperial raiding/trading expeditions they sent down the coast of West Africa…)

But back to Denis: In 1289 he buried his hatchet with the Vatican by signing a far-reaching “Concordat” with it that brought to an end 23 years of sparring between Lisbon and the Vatican. It was just the following year that he decreed the use of Portuguese (rather than Latin) as his polity’s official language…

Denis, for what it’s worth, was also an author and a generous patron of the arts who reportedly ordered the translation of many literary works into Galician-Portuguese.