This is another two-main-story year; and once again the two main stories are about the handful of countries bordering the North Sea and the Atlantic that have been carving out a role for themselves as bosses of the world’s sea-lanes and therefore (soon enough in the future) of the whole world.

The major “subsidiary” story of note this year is that in Ethiopia, in March, a person called Susenyos (ሱስንዮስ sūsinyōs) defeated the combined armies of the people ruling Ethiopia, which made him the Emperor of Ethiopia. He would rule until 1632. One of the interesting things about him was that he was close to Manuel de Almeida, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary who’d been living in Ethiopia for a while and in 1622, he converted to Catholicism. The Portuguese had been somewhat involved in Ethiopia since the 1540s. Anyway, Susenyos’s conversion did not go down well with most of the Ethiopian leaders and people who were members of the ancient Ethiopian Orthodox church. (Which got restored to power after Susenyos was killed in 1632.)

Now, to the two main stories. The English first this time.

English settlers plant colony in “Jamestown”

In late 1606, the first group of three small-ish ships set sail from London to establish the “London” branch of the Virginia Company’s first settlement in North America. The best description on English-WP of how that was organized and what happened there is this page, on expedition leader Edward Maria Wingfield. He was born in 1551 in the south of the English Midlands. His dad died when he was seven, and from his late teens he had a career as a soldier and Ireland and the Netherlands, and a short period as a settler in one of the English “Plantations” in Ireland. He came from a fairly well-established family, studied law, and served for a while in parliament.

He was one of the people who worked to get the “Virginia Company” formed in 1606. He was one of the supplicants for the charter who was spelled out by name in its text, and a non-trivial shareholder in the company– indeed, the only shareholder who sailed aboard the first flotilla. Also, along with his cousin he recruited around 40 of the first group of 105 settlers aboard those boats.

The flotilla left London under the command of Christopher Newport, an experienced mariner. But the Council of the Virginia Company in London specified that Newport was only in charge until they made landfall in America, at which point (April 26, 1607) Newport opened a sealed box that the Council had given him, that contained the names of the 13 people appointed to be the Governing Council of the land-based colony. Those 13 elected a “President”, and it was proibably little surprise that Wingfield was the winner.

The flotilla had sailed into the mouth of a river, known to them from maps previously made and named by them as the “James River.” It is in the south of today’s Virginia, on the western shore of the Chesapeake Bay, near the mouth of the Bay. One first decision was over where to build the first settlement which they had (probably correctly) determined should be heavily fortified– as much against the possibility of a naval assault against it by the French or Spanish as of a land or river assault against it by the Indigenes. Wingfield vetoed the first site proposed and decided on one on a marshy island on the river’s north bank that became known as “Jamestown.”

He immediately set nearly all the settlers to work building the fort, which he had designed to be triangular and proportioned thus: “(140 yards by 100 yards (91 m) by 100 yards (91 m) plus three artillery “blisters” of 20 yards (18 m) each) – involving the felling of perhaps 500–600 30 ft-trees, cutting them in half and burying one end firmly in the ground: a vast task.” The settlers repulsed one attack by the local Indigenes (whom they called “Naturals”) in late May.

In addition to building the fort, Wingfield planted some crops. But neither the settlers nor the indigenous Powhatans were having a good time with agriculture in those years, which saw “the worst seven-year dry-spell (1606-1612) in nearly 800 years.” So food was very sparse and many of the settlers resented the hard work that Wingfield was ordering them to do.

Then, this: “On 10 September 1607, amid starvation and attacks from native tribes, Wingfield was arrested and deposed from his presidency.”

Wingfield was put on the next boat back to London to face trial there on various, quite possibly trumped-up, charges. (The next “President” of the Governing Council was captured and very gruesomely killed by the Indigenes in 1609. Then, the third president was also, like Wingfield, deposed by his fellow settlers.)

In much of the telling of the origins of the Jamestown settlement, this is presented as the “birth of democracy in America”– presumably because the small group of men named by the Virginia Council in London to be form the Governing Council got to “vote” for, and then against, their “president”. Settler-colonial “democracy”– which is absolutely never based in any way on the “consent” of the people whose lands get invaded and stolen– is a very strange thing.

The banner at the head of this post is a 19th-century painting of an incident in which John Smith thought he could win the support and the vassalage of local leader Powhatan by giving him a European-style crown. But Powhatan refused to kneel before Smith to receive the crown, so that did not go well…

Here’s the famous map that John Smith made of the Chesapeake area:

Meantime, a few other pieces of relevant news about the English:

- In August 1607, a small group of colonizers from the “Plymouth” branch of the Virginia Company made landfall on the coast of Maine, not far from Kennebunkport and made plans to start building a fortified settlement. Their colony lasted only 14 months.

- June 1607 saw the “Newton Rebellion”, part of the broader “Midland Revolt”, which was mainly against landowners who were enclosing common lands for their own private profit: “In early June, over a thousand protesters, including women and children, gathered in Newton, near Kettering, Northamptonshire to protest against the enclosures by pulling out hedges and filling ditches. King James I ordered his deputy lieutenants in Northamptonshire to put down the riots.” There was some trouble finding forces willing to act against the rebels. But eventually, “the gentry and their forces charged. Forty or fifty were killed in the pitched battle and the leaders of the protest were hanged and quartered.”

- In September, the Irish Earls Hugh O’Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone, and Rory O’Donnell, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell, and about ninety followers, left Ulster in Ireland for mainland Europe. As English-WP notes: “Their permanent exile was a watershed event in Irish history, symbolizing the end of the old Gaelic order.” It would be more than 300 (often extremely difficult) years before most of Ireland could throw off the yoke of England’s settler-colonial rule.

Dutch expeditionary fleet clobbers a Spanish fleet

You will recall that in 1604, the English and Spanish kings had concluded a momentous peace agreement. The Protestant Netherlanders who had been close allies of the English until that point were notably not included. Indeed, since 1604 they had escalated the raids and assaults they launched against the ships, trading-posts, and port cities of the Spanish-Portuguese joint monarchy. Thus far, none of the raids they had launched against Spanish-Portuguese targets in waters close to the Iberian Peninsula had succeeded.

This year, in April, they scored a bull’s-eye in the Bay of Gibraltar, a broad, south-facing bay just west of the Rock of Gibraltar.

On April 25, a Dutch fleet of 26 warships surprised and engaged a Spanish fleet of 21 ships that were at anchor in the bay. With no ships’ losses of their own, the Dutch destroyed 5-10 large Spanish galleons and 9-12 smaller vessels. “The Spanish fleet was covered by a fortress, although the Dutch fleet was out of range of its guns at all times and [the guns] could not intervene in the battle.”

Also, this:

Following the destruction of the Spanish ships, the Dutch deployed boats and killed hundreds of swimming Spanish sailors. The Dutch lost 100 men including Admiral Van Heemskerk [their commander.] Sixty Dutch were wounded. Depending on the sources, most or all of the Spanish ships were lost and between 350 and 4,000 Spaniards were killed or captured. Álvarez de Ávila was amongst the dead.

The battle resulted in a 12-year truce in which the Dutch Republic achieved de facto recognition by the Spanish Crown.

Well, the 12-year truce would not actually come until 1609; and another big factor in the Spanish realizing they needed to conclude it was that in 1607, yet again, their government went bankrupt. Financial management seems to have been a very weak skill-set for the Spanish– unlike the Dutch and the English. The global trading companies established by England and Netherlands both had strong accounting and auditing departments. Maybe that’s an advantage of having a private “joint stock” company to run those ventures: the shareholders would all to some extent be looking at the books over each other’s shoulders, and certainly supervising the spending of the expedition heads fairly closely. Whereas if you’re a Spanish monarch who has gotten used to great floods of (actually, very inflationary) silver coming into your coffers every year, well, who needs to bother with checking the books??

Finally, re Spain, lest we forget: Regardless of the destruction of the fleet in the Bay of Gibraltar or financial ruin in the heartland… in “New Spain” the relentless task of building colonial settlements continued. Some examples of what happened in 1607:

- Philip III established a new “Captaincy General of Cuba” as part of larger plans to defend the Caribbean against “foreign”, that is non-Spanish, threats.

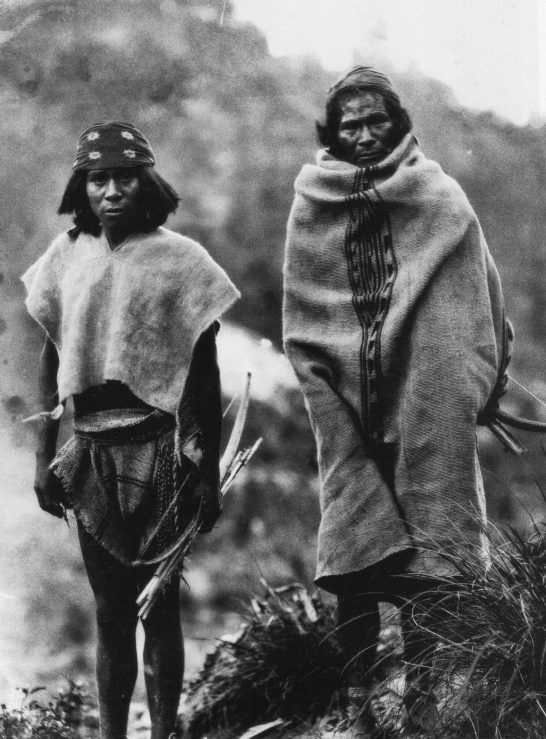

- The Jesuits established a mission to The Rarámuri or Tarahumara, a group of indigenous people living in the state of Chihuahua in Mexico.

- Settlers in Colombia established the chapel of Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de la Popa at the top of Mount Popa, in Cartagena de Indias, and the settler-town of Tena in the Tequendama Province.