1608 CE was mainly just a routine year in that early-ish era of European imperial growth. Conquistadors conquistadoring, Portuguese and Dutch duking it out in the East Indies, etc. One interesting news item was that Irish resistance to English settler-colonialism was not, as I wrote yesterday, completely defeated in 1607.

Also of note: How extremely fractious-among-themselves participants in the early colonizing ventures in North America of both England and France turned out to be.. I wonder why? Maybe it was the arrogance and the toxic masculinity of all those early colonists?

Here’s a quick review of the year’s three big stories:

1. Champlain founds Quebec

Samuel Champlain, the French colonizer who had come to “Acadia” in 1603, this year came back with a new commission from big-time French fur-trader Pierre Dugua de Mons to start a new French colony and fur-trading center on the shores of the St. Lawrence River. He sailed three ships over from France, filled with sailors, colonists, and weapons and other basic supplies for members of both groups. They chose Quebec. Champlain later wrote:” I arrived there on the 3rd of July, when I searched for a place suitable for our settlement; but I could find none more convenient or better suited than the point of Quebec, so called by the savages, which was covered with nut-trees.”

He ordered his men to gather lumber by cutting down the nut-trees to use to build huts and also, presumably, fortifications. (Maybe leaving the nut-trees standing would have served the colonists better over the long haul?)

Then this:

Some days after Champlain’s arrival in Quebec, Jean du Val, a member of Champlain’s party, plotted to kill Champlain to the end of securing the settlement for the Basques or Spaniards and making a fortune for himself. Du Val’s plot was ultimately foiled when an associate of Du Val confessed his involvement in the plot to Champlain’s pilot, who informed Champlain. Champlain had a young man deliver Du Val, along with 3 co-conspirators, two bottles of wine and invite the four worthies to an event onboard a boat. Soon after the four conspirators arrived on the boat, Champlain had them arrested. Du Val was strangled and hung in Quebec and his head was displayed in the “most conspicuous place” of Champlain’s fort. The other three were sent back to France to be tried.

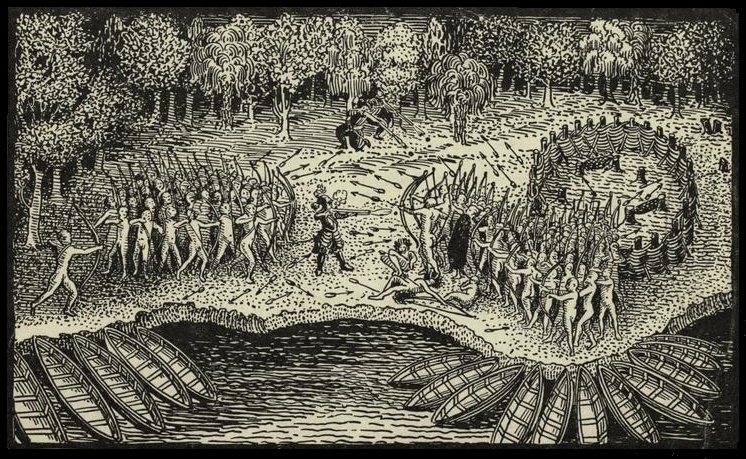

The following year, he headed off with an exploration party to “explore” the present-day Richelieu River and to entangle himself in conflicts among local Indigenous groups. In late July 1609 when he was leading a party of just two other Frenchmen and 60 “natives”, they met a group of 250 “Haudenosaunee”, apparently part of the powerful Iroquois federation.

English-WP tells us that:

In his account of the battle, Champlain recounts firing his arquebus and killing two of [the three Haudenosaunee leaders] with a single shot, after which one of his men killed the third. The Haudenosaunee turned and fled. This action set the tone for poor French-Iroquois relations for the rest of the century.

Ah, the wonders of European technology.

2. England’s Jamestown colony has a tough year (its neighbors, probably worse)

When we left Jamestown last year, the settlers had just deposed their “President”, Edward-Maria Wingfield, and sent him back to London to be tried on trumped-up charges. I failed to note that at the end of the year, a certain settler called John Smith had been seeking food along the Chickahominy River and been captured by Opechancanough, a member of the Powhatan tribe. He claimed to have had lost of adventures but those claims were later contested. Anyway, he got back to Jamestown in January.

But meantime the little settlement had suffered a bad fire, some bad winter weather, and near-starvation. WP tells us:

Two-thirds of the settlers died before ships arrived in 1608 with supplies and German and Polish craftsmen, who helped to establish the first manufactories in the colony…

The delivery of supplies in 1608 on the First and Second Supply missions of Captain [Christopher] Newport had also added to the number of hungry settlers. It seemed certain at that time that the colony at Jamestown would meet the same fate as earlier English attempts to settle in North America, specifically the Roanoke Colony (Lost Colony) and the Popham Colony, unless there was a major relief effort. The Germans who arrived with the Second Supply and a few others defected to the Powhatans, with weapons and equipment. The Germans even planned to join a rumored Spanish attack on the colony and urged the Powhatans to join it…

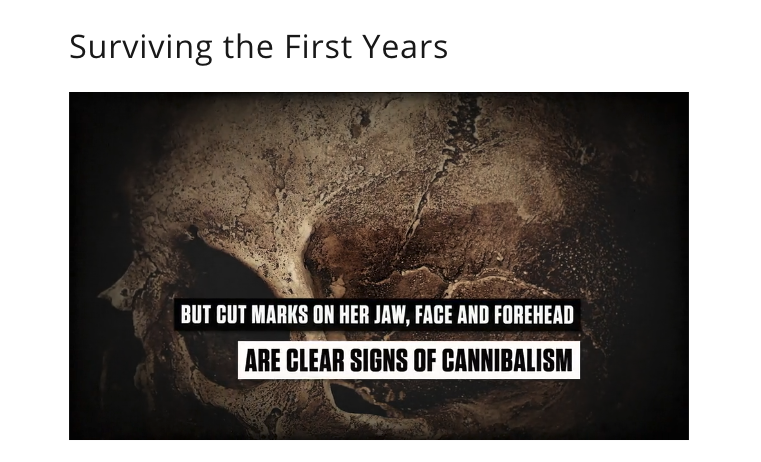

The Spanish apparently sent a reconnaissance ship to suss out how “Jamestown” was getting along. In July 1609 an English re-supply mission arrived that was large enough to indicate to the Spanish that the little English colony would not be easy to capture… But Jamestown continued to suffer from extreme hunger which led to some colonists dying of starvation and others to engaging in cannibalism during the winters that followed.

The banner image above is a still from a short “History Channel” film about the early years of Jamestown, presented on this page. Here’s another still, presenting some archeological evidence about the cannibalism of the early settlers.

3. Another surge of Irish resistance (but quelled)

In April 1608, the Irish knight Sir Cahir O’Doherty launched a rebellion with an attack on the small English garrison town of Derry in Ulster, which he was able to take thanks to the element of surprise. The town was then almost entirely destroyed by fire.

Interestingly, O’Doherty, the Gaelic Lord of Inishowen, had–like some other Irish lords–been allied with the English during the Nine Years’ War of 1594-1603. But he grew alienated from the English after (a) the English treated the rebel lords Hugh O’Neill and Rory O’Donnell relatively leniently by restoring their lands to them after they were defeated in battle; and (b) a new Governor of Derry was sent over from London who was much less friendly to O’Doherty than the previous governor.

So once they had decided to rebel, O’Doherty and his ally Phelim MacDavitt were fairly easily able to capture the strongpoints of the small, fortified English settlement-town at Derry, with about “half a dozen men … killed on each side during the brief fighting.” They then burned down all the 85 houses in the town.

Here’s what happened afterwards:

O’Doherty gathered support following his victory at Derry, and his forces ranged across Ulster burning several other settlements. O’Doherty possibly hoped that he would be offered a settlement by the government, as had happened during rebellions over previous decades, rather than risking a long and expensive war. This prospect was dashed by the quick response of Sir Arthur Chichester in Dublin who oversaw the dispatch of what reinforcements he could spare northwards and the raising of loyal Gaelic forces. They soon recaptured the burnt-out ruins of Derry. The main force of rebels were defeated at the Battle of Kilmacrennan, where O’Doherty was killed. A group of remaining rebels made a final stand at the Siege of Tory Island, but the rising had been overcome quickly.

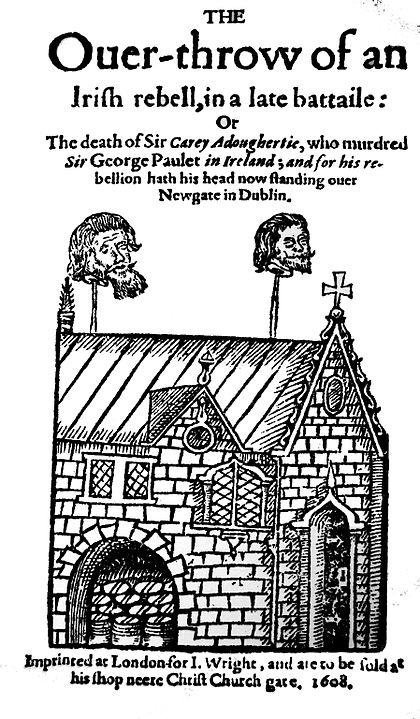

After O’Doherty was killed, “the rebellion began to fall apart. A number of those taken prisoner were tried for treason in Lifford in civil courts and executed. The most prized prisoner taken was Phelim MacDavitt, who was wounded in woodlands and forced to surrender. He was executed and his head put on display alongside O’Doherty’s at Newgate down in Dublin.”

At a broader political level, one consequence of the O’Doherty’s uprising was that,

[A]fter O’Doherty’s attack on Derry, the [English] government no longer trusted many of the Gaelic leaders, even those who had not risen in revolt, and brought in a more ambitious scheme of importing large numbers of English and Scottish settlers. Gaelic leaders therefore got a smaller share of the land division than had been earlier planned. Derry was rebuilt following its destruction and was renamed ‘Londonderry’, becoming an integral part of the new plantation and the last walled city to be built in western Europe.