The short version of what was happening in world politics in 1596 was that, as the English and Spanish duked it out in big sea battles in the North Sea (also, in the Caribbean), and the Ottomans and Habsburgs duked it out in big land battles in Hungary– suddenly, poof!– the wily Dutch snuck around everybody else and started building their long-distance empire in the East Indies.

Well, I write there “the Dutch”, but of course Netherlands itself was still to some extent an object of contestation. But clearly, the situation around its emerging capital of Amsterdam was stable enough to allow the city’s merchants, investors, and ambitious, heavily militarized “explorers” to lay big plans to bypass (or even, replace) Portugal’s long-distance trading empire in the East Indies.

Portugal was for now hanging on to what it had in Sri Lanka, however…

I’ll gallop quickly through all those other events and then focus on what a bunch of Dutch adventurers were up to in Banten, in today’s Indonesia.

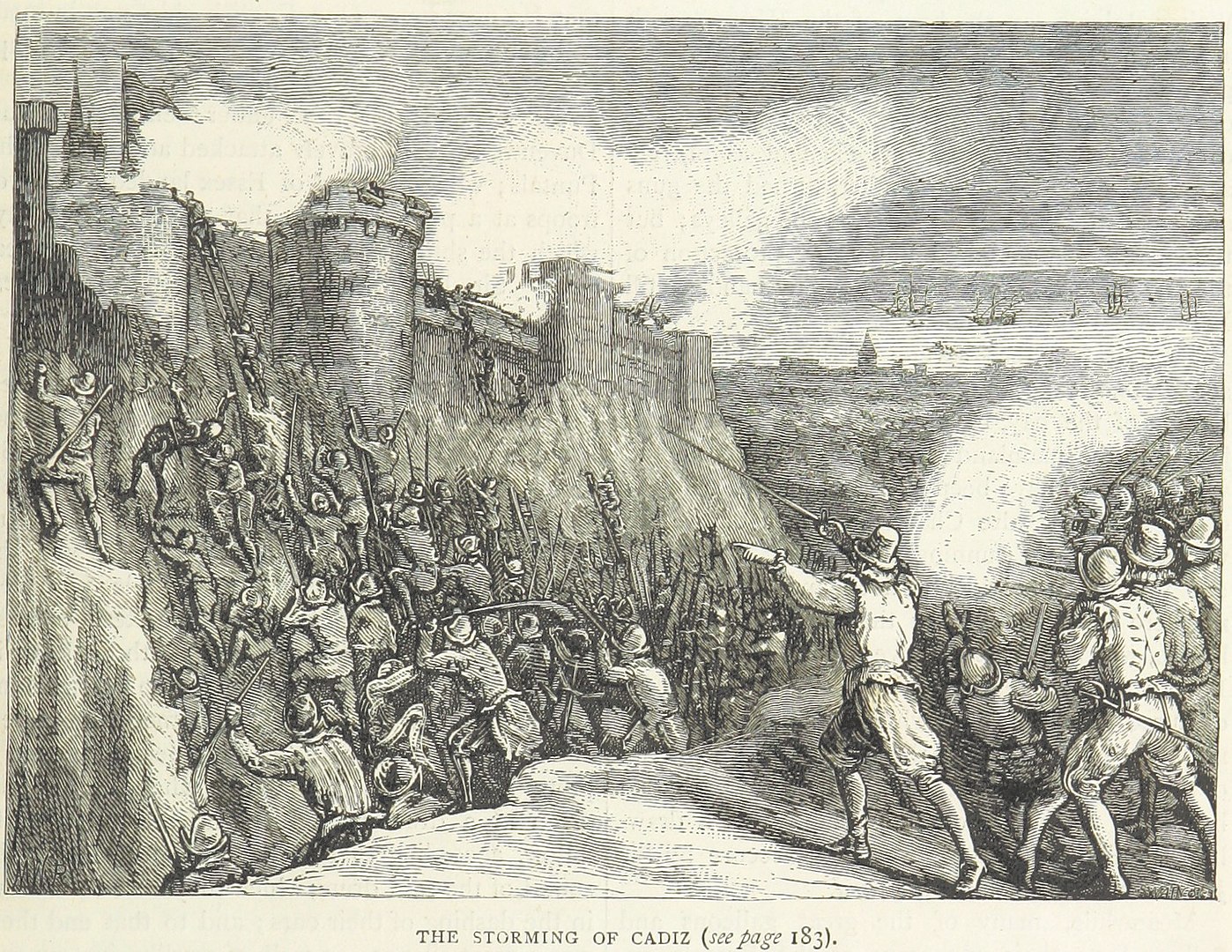

- In late June,a combined English-Dutch fleet comprising 150 ships (17 from the Royal Navy, the rest presumably privateers) set out for Cádiz, which was the home port of Spain’s annual treasure fleet. Roughly half of the 14,000 men aboard were soldiers. The admirals had planned and proceeded to execute a well-ordered plan to sack and plunder Cadiz, which had a reported 6,000 inhabitants. “Churches and people’s houses were the object of pillaging, although the troops did respect the integrity of the people themselves”– including, apparently, the women. Citizens of Cádiz were allowed to leave the city in exchange for a ransom of 120,000 ducats and the freedom of 51 English prisoners captured in past campaigns: they exited with nothing more than they could carry. Some of the officers on the invasion force wanted to stay in the city, but the commanding admiral (probably wisely) said that would be too risky. He made it a “hit and run” operation and ordered a return to England, even declining to divert to plunder yet another incoming treasure fleet. The sacking of Cádiz was a big setback to King Philip and contributed to his decision later in the year to (yet again) declare bankruptcy. But–

- In late October, 69-year-old Philip and his admirals launched yet another Armada against England, with the plan also being to support the anti-English uprising in Ireland. He dispatched a total of between 126 and 140 ships on this mission, with around 19,500 men aboard. But this Armada was clearly pulled together far too quickly: “Lack of food and money as well as potential mutiny forcibly delayed the expedition which infuriated Philip.” The weather also did not help. The ships encountered an unexpected gale-force wind as they rounded Cape Finisterre in northwest Spain. Many of the ships were battered beyond repair, and none of them made it any further. The commander of a British fleet sent to engage the Spanish found, instead of an Armada, “only floating wreckage and bodies.”

- Also in late October, the new Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed III, led a force of between 50,000 and 100,000 man in a battle against a combined, similarly sized Habsburg-Transylvanian force near the village of Keresztes (also, in Turkish, Haçova), in northern Hungary. The Ottomans routed the Habsburg-led army but Ottoman casualties were too high for them to continue further. Instead, most of them took the month-long march back to Constantinople, where they– and presumably especially Mehmed III– received a lavishly-funded victors’ welcome.

- In 1596, in today’s Sri Lanka, the king of fiercely independent Kandy had named another anti-Portuguese rebel called Edirille Bandara (also known as Edirille Rala, or Dominicus Corea) as King of neighboring Kotte and Sitawaka. King Vimala of Kandy held a lavish, large-scale investiture ceremony for the new king, involving elephants and so on…But on July 14, 1596, the Portuguese captured King Dominicus Corea and executed him.

And now….

Dutch empire-builders reach the Spice Islands

I guess I hadn’t realized until recently how important just plain old black pepper was in the development of some European-origined global empires. But for the group of Dutch merchants who had formed the Compagnie van Verre trading company in 1594, it was the key to their (always militarized) business plan.

In 1592 CE, a Dutch guy called Cornelis De Houtman had gone to Lisbon as a spy, to learn as much about the now fairly mature trading empire the Portuguese had built in the Moluccas, in today’s Indonesia. He returned to Amsterdam with his findings at about the same time that Jan Huygen van Linschoten returned there with all the commercial secrets he had picked up in Portuguese Goa. These two were among the founders of the Compagnie van Verre, which in April 1595 had sent out an armed trading party of four ships to make contact with the list of potential trading partners they had identified.

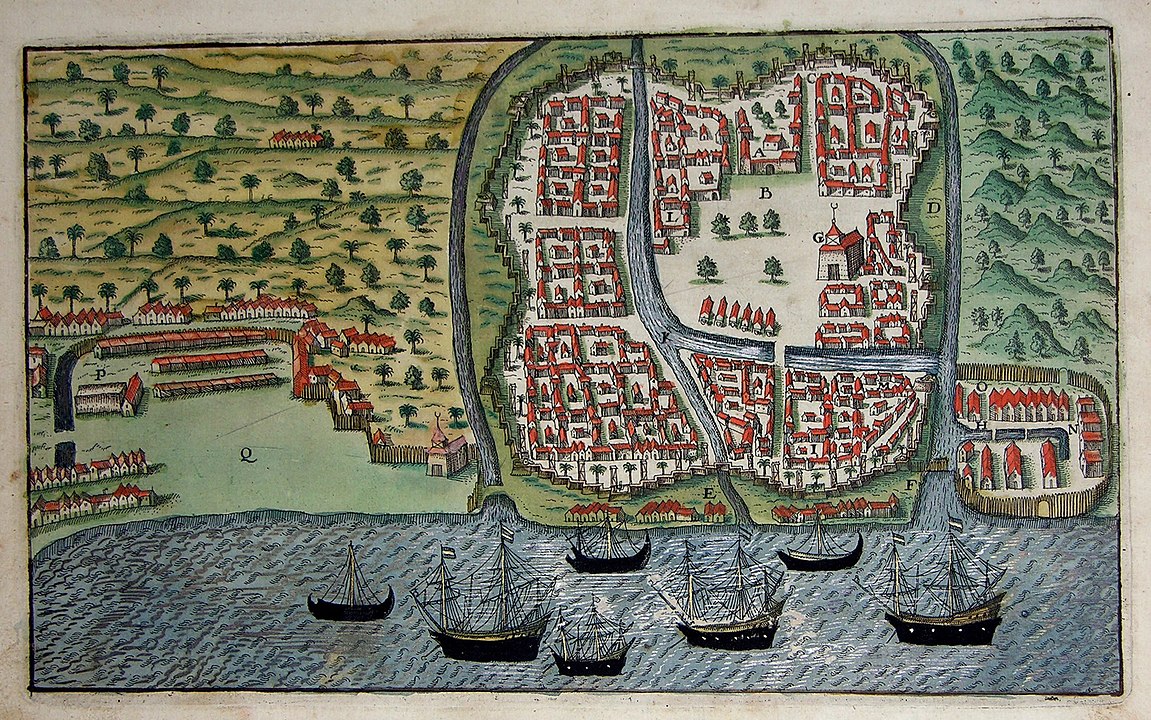

First on the list was the Sultan of Banten, a small sultanate that sat astride the Sunda Strait– a route Van Lischoten had judged would be easier for them to use than the more northern Malacca Strait, which was the favored route of the much more numerous (and also well-armed) Portuguese trading vessels.

This page on English-WP tells us:

The voyage was beset with trouble from the beginning. Scurvy broke out after only a few weeks, due to insufficient provisions. At Madagascar, where a brief stop was planned, seventy people had to be buried… After the death of one of the skippers, quarrels broke out among the captains and traders, one was imprisoned on board and locked up in his cabin. In June 1596, the ships finally arrived at Banten.

De Houtman was introduced to the Sultan of Banten, who seemed friendly, writing “We are well content to have a permanent league of alliance and friendship with His Highness the Prince Maurice of Nassau, of the Netherlands and with you, gentlemen.” But De Houtman, was “undiplomatic and insulting” to the sultan, and was turned away for “rude behaviour”, without being able to buy any spices.

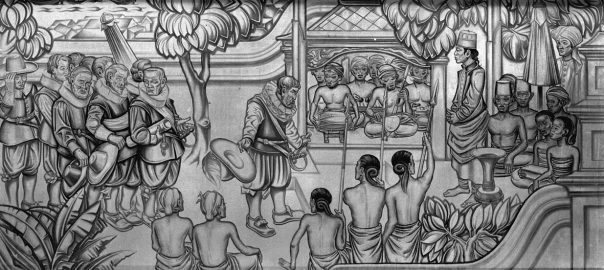

(By the way, the banner image at the top of this post is a much later Dutch artwork depiction of De Houtman meeting the Sultan of Banten.)

The ships then sailed east to Madura, but were attacked by pirates on the way. In Madura, they were received peacefully, but De Houtman “ordered his men to brutally attack and rape the civilian population in revenge for the unrelated earlier piracy.” They then went to Bali, where in February 1597 they met the island’s sultan and managed to obtain a few pots of peppercorns. Since the sailors were now quite fed up, it was decided not to go to the Moluccas but to return to Holland. That evening another one of the skippers died. “De Houtman was accused of poisoning him.”

On the trip back, when they reached Saint Helena, the Portuguese ships that controlled the port prevented them from taking on water and supplies. Of the total of 249 sailors who had left in 1595, only 87 returned, and they were “too weak to moor their ships themselves.”

Though the immediate outcome of this voyage was mediocre at best, it clearly whetted the appetite of Dutch investors for further “East Indies” expeditions: “Within five years, 65 more Dutch ships had sailed east to trade. Soon, the Dutch would fully take over the spice trade in and around the Indian Ocean.”

Move over, Portugal!

By the way, the political situation in Banten that De Houtman encountered during the 1596 voyage was also interesting. According to this good page on English-WP on the Sultanate of Banten, in 1596 the Sultan there, Muhammad, was an energetic 25-year-old who was the third generation of Muslim rulers in Banten, the Sultanate having been established by his grandfather in 1522. At some undisclosed point during 1596– before June? after June? who knows?– Muhammad,

launched a military campaign against the principality of Palembang — both by naval fleet and by land army marching through Southern Sumatra. At that time, Palembang was still a Hindu-Buddhist polity… which was regarded by Muslim Banten as a pagan state. Inspired by his illustrious grandfather Hasanuddin and his valiant father Maulana Yusuf, that conquered the pagan kingdom of Sunda, Muhammad was eager to find fame of his own by expanding his realm. By 1596 the siege of Palembang was set in place, and when the victory seems within his grasp, a sudden tragedy happened as a cannonball struck and killed the king on his ship… With the sudden death of the young monarch, Banten’s expansionist policy was shattered, as the troops retreated and sailed home

Muhammad’s son Abulmafakhir, an infant of just a few months old, succeeded him. It is not clear which of these two rulers (or, in the case of the baby, his regents) was the power with whom De Houtman had his dealings.

Anyway, that WP page continues with this:

In 1600 the Dutch set up the Dutch East Indies Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC) with the aim to bypass the spice trade. Unlike the Portuguese in Malacca which at that time quite harmoniously integrated into the Asian trade system involving various states in the region including Banten, Dutch as the newcomer had a different approach, they came to the scene hellbent to seize control of spice trade from Far East all the way to Europe. The Portuguese and Dutch fought fiercely for influence in Banten in the early 17th century, and erupted into a full-scale naval battle on Bay of Banten in 1601, in which the Portuguese fleet was crushed.

Other Europeans were soon to follow. The English, who started to sail to the East Indies from around 1600, established a permanent trading post in Banten in 1602 under James Lancaster. In 1603, the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Banten.

With the infant king and the absence of a decisive central figure, the government was taken over by the regency council. The expulsion of the Portuguese had led to both Dutch and English vying for control in the city. The court itself was divided into two competing factions, and civil war erupted in 1602. Peace was not restored until 1609 when one of the nayaka nobles, Prince Ranamanggala ascended to power as a new regent.

Ranamanggala restored the state’s authority on commercial affairs; levying taxes, imposing price and volume of trade, and exiling the ponggawa elites to the port of Jayakarta in the east, stripping the merchants’ power altogether. This new strong policy which showed disregard for the principles of free trade, did not sit well with the Dutch and the English. A few years later the Dutch and English followed suit, they went to Jayakarta to establish a new trade post.