Lots of familiar events in 1595 CE. In Constantinople, Sultan Murad III died, being succeeded by Mehmed III, one of whose first acts was to– guess what!– kill off a record number of 19 of his brothers. (Intriguingly, at one point earlier on, Murad’s sister Ismihan had been worried he was impotent and not producing enough potential heirs. A palace doctor was called in: his potions proved astoundingly effective, leading to the reported births of more than a hundred children fathered by Murad. The slaughtered 19 were the unlucky ones among them.)

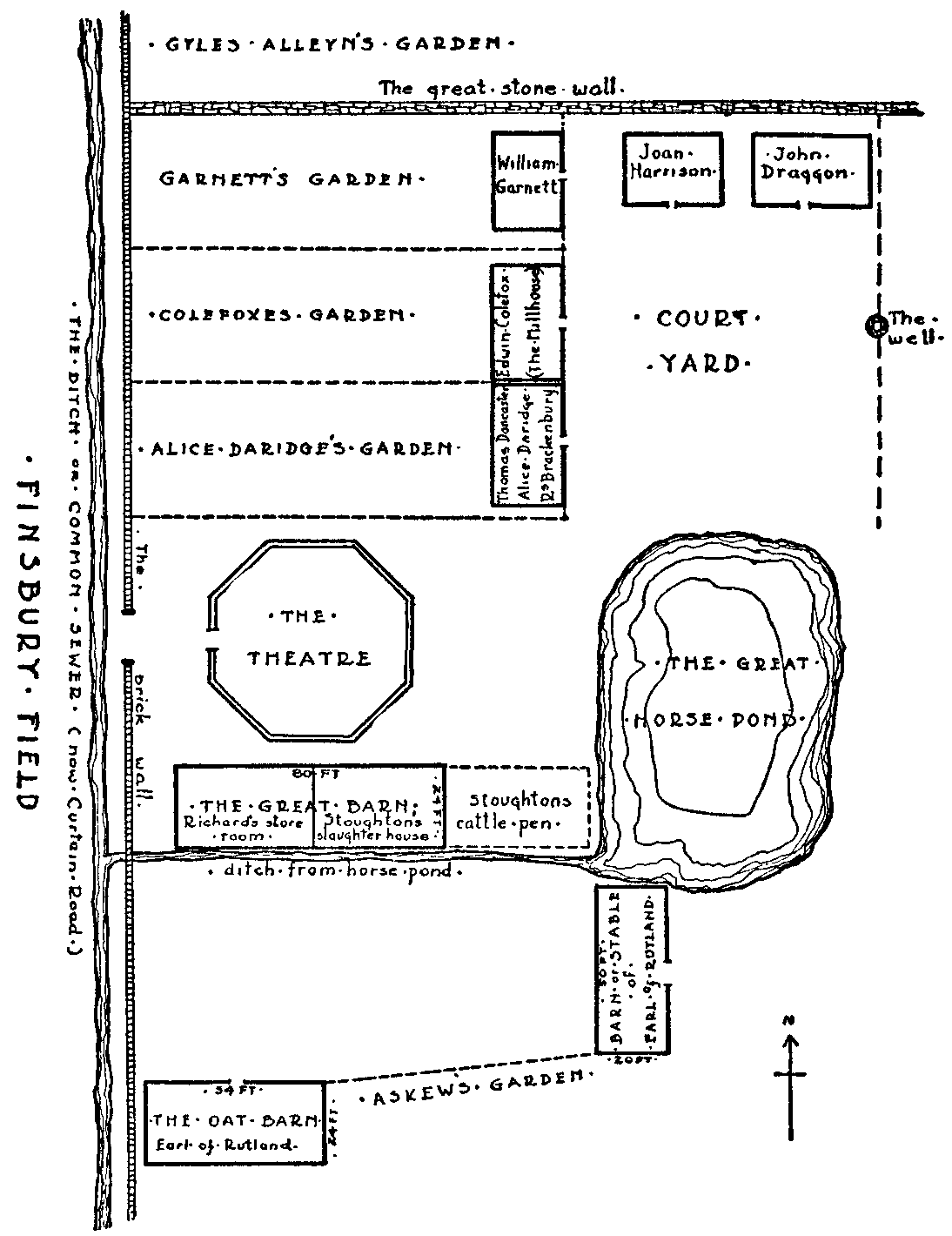

New in 1595: In London, the “Lord Chamberlain’s Men” acting troupe debuted no fewer than three plays written by 31-year-old William Shakespeare. These were Richard II, Romeo and Juliet, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. English-ness was becoming a recognizable thing– hand-in-hand with the numerous projects that London merchants and investors were pursuing, in alliance with Queen Elizabeth and her court, that aimed at building a worldwide trading empire.

But those empire-building projects still had to be pursued in competition with (and to a great degree parasitically upon) the much more fully developed colonial and trading empires that the now-united Iberians had built all around the world…

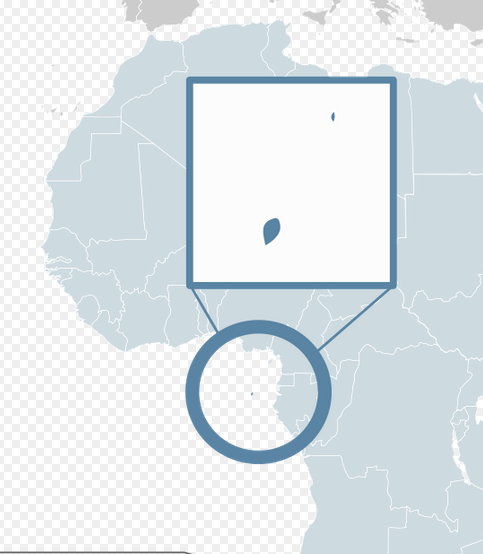

So first, we’ll look at the series of clashes 1595 saw between the English expeditions in and across the Atlantic and their Iberian competitors; and then we’ll look at the big rebellion that Africans enslaved in the Portuguese-held island of São Tomé mounted in 1595– the first of many anti-colonial uprisings the island would see over the centuries that followed.

English and Iberians clash in Americas

There are records of four significant clashes in 1595 between English naval expeditions and defenders/holders of Spanish and Portuguese colonials posts in the Americas. In addition to these battles, the land and naval forces of the two sides also fought in the continuing war in the Netherlands; and a Spanish landing party made a brief landing in July in Cornwall, in the West of England.

So, here were the clashes:

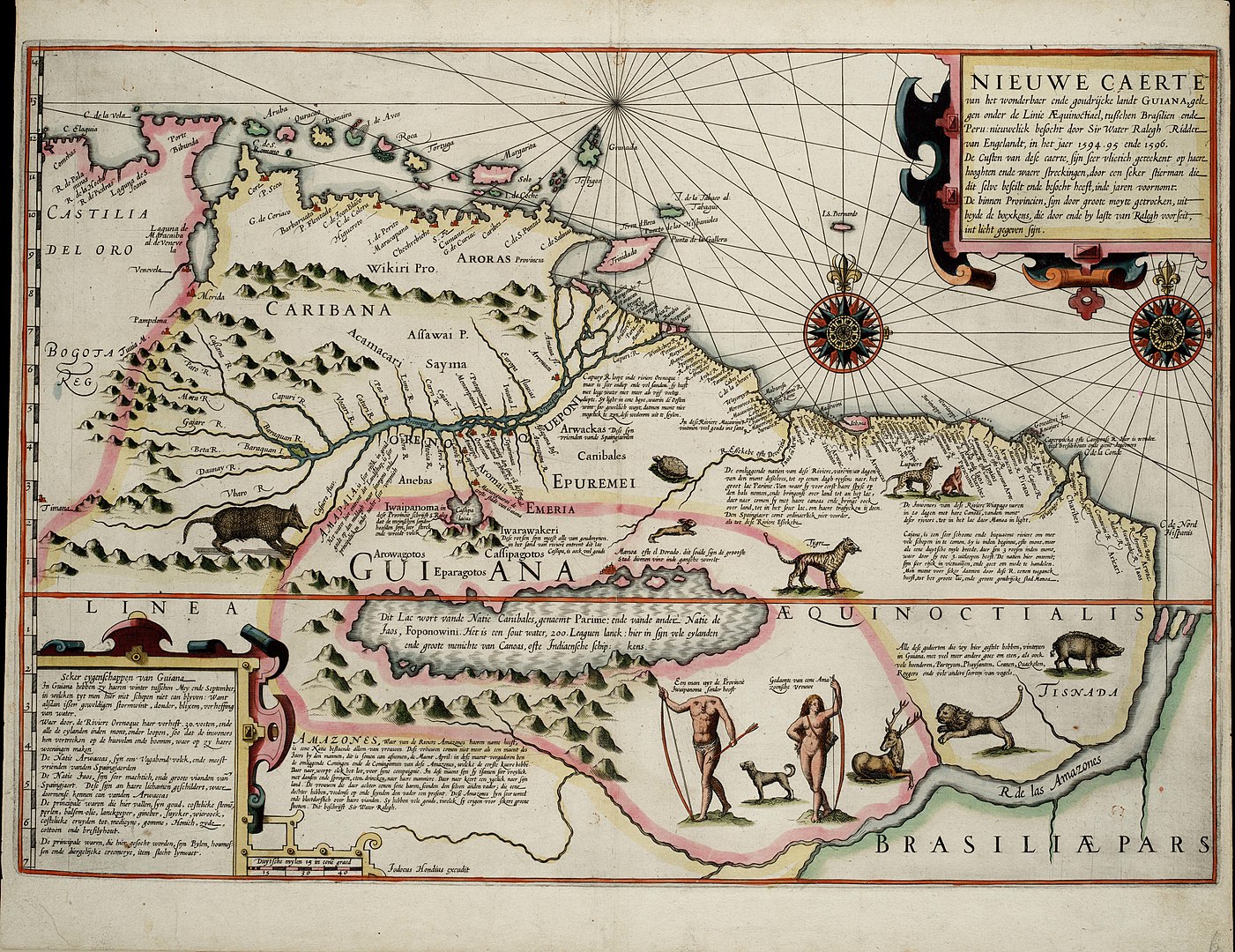

- In February, the controversial English captain Walter Raleigh, newly released from jail in London, set off with a small group of four ships with the goal of finding the fabled lost of city of “El Dorado”, which he believed to lie in the interior of today’s Venezuela– then controlled by the Spanish. En route he sailed by the Canary Islands where he captured a Spanish ship and its cargo and emptied a Flemish ship of its cargo. In April, he reached Trinidad and captured the small Spanish garrison there, fortifying it to use as a rearguard base while he proceeded to Venezuela and to a trip up its lengthy Orinoco River, penetrating some 400 miles into the Guiana Highlands. As he traveled up the Orinoco, he told people in the various Indigenous villages he encountered that he was an enemy of the Spanish, winning lots of friends that way. However, he did not discover “El Dorado” or anything else of much value and was treated with derision by his investors when he returned to London. (The banner image above depicts Raleigh taking captive the commander of Trinidad’s Spanish garrison.)

- In October 1594, English navigator James Lancaster– whom we last encountered sailing to Penang in 1591, set out from Plymouth with a small group of three armed merchant-ships with the goal of “connecting with” the high-value products of the sugar and spice plantations the Portuguese had established in Brazil. (Before the Iberian Union was formed, Lancaster had traded with the Portuguese and spoke their language. Now, because the Iberian Union had put the Portuguese in alliance with the Spanish, he was more free to plunder them!) On the outward trip, he and his man captured several Spanish and Portuguese ships as “prizes”. In March 1595, the fleet that now numbered 15 ships reached Recife in the extreme east of Brazil. They captured the town and the Portuguese fort built to guard it, and stayed for long enough to empty its warehouses in a systematic manner for the trip back home, leaving just as a Portuguese counter-attack was about to break through and re-take it. Though much of Lancaster’s fleet was scattered on the way back, they only lost one boat. His investors, who included Queen Elizabeth, were delighted with the large profits he brought them. One of the looted items of greatest value was a new collection of Portuguese rutters (detailed navigation manuals), which would prove extremely helpful to the East India Company, which Lancaster would help to form just five years later.

- In August, Francis Drake and his buddy, England’s “pioneering” slave-trader John Hawkins, set sail from Plymouth at the head of a fleet of 27 ships, with the goal of capturing the Spanish port at San Juan, Puerto Rico. Along the way there, the nine ships in the rear of the fleet got into a battle with a small force of five Spanish frigates near Guadalupe, in the Caribbean. The result was a Spanish victory. The Spanish captured one of the English ships and learned from its captain about the plan to capture San Juan– and they were able to get advance warning to San Juan of the upcoming raid.

- Partly as a result of the timely intelligence, the Spanish garrison at San Juan was much better defended than Recife had been; and after a fierce two-day battle in late November 1595 the defeated English abandoned the effort. Hawkins had died of a fever shortly before the battle. After the defeat, Drake decided to head for Panama– maybe hoping to catch the Spanish mule trains laden with silver there? Instead, he caught dysentery and died. I imagine the investors in his expedition were less than delighted with his achievements.

Large rebellion by the enslaved in São Tomé

São Tomé and and its smaller sister-island Príncipe were reportedly uninhabited when some Portuguese explorers arrived sometime around 1470 CE. The first successful settlement of São Tomé was established in 1493 by Álvaro Caminha, who received the land as a grant from the Portuguese king. Príncipe was settled in 1500 under a similar arrangement. Attracting settlers proved difficult because of the remoteness and near-equatorial heat of the islands, and most of the earliest inhabitants were “undesirables” sent from Portugal, including convicts and Jews.

The settlers found the volcanic soil of the region suitable for agriculture, especially the growing of sugar. But the cultivation of sugar required a lot of manpower, so the Portuguese began to import large numbers of enslaved Africans from the mainland– mainly from the Gold Coast, the Niger Delta and the Kingdom of Kongo.

In 1515 the introduction of a water-powered mill soon led to the mass cultivation of sugar. In 1517, a local administrator would report to the king that, “The fields are expanding and the sugar mills, too… And the [sugar] canes are the biggest I have ever seen in my life.”

In the early years, the conditions of enslavement on the island seemed relatively relaxed. For example, in 1515 a royal decree granted manumission to African wives of white settlers and their mixed-race children; in 1520, a royal charter allowed property-owning, married, free mulattoes to hold public office. But following the introduction of the big-plantation system, the conditions of enslavement were tightened. More slaves started to run away to the mountains, where they developed little communities known as macambos, many of which faced starvation. Throughout the 16th century, English-WP tells us, there were frequent clashes between the people of the macambos and the plantation owners.

Then this:

The greatest slave revolt occurred in July 1595, when the government was weakened by disputes between the bishop and the governor. A native slave named Amador recruited 5000 slaves to raid and destroy plantations, sugar mills, and settler houses. Amador’s rebellion made three raids on the town and destroyed 60 of the island’s 85 sugar mills, but were defeated by the militia after three weeks. Two hundred slaves were killed in combat, and Amador and the other rebel leaders were executed, while the rest of the slaves were granted amnesty and returned to their plantations. So ended one of the greatest slave uprisings to that time. Smaller slave rebellions followed in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Early in the 17th century, the sugar plantations of São Tomé would start to face massively increased competition from the (also slavery-reliant) sugar plantations built by English, Spanish, and other Western empire-builders in the Caribbean, so sugar cultivation in São Tomé diminished. By the mid-17th century, the island had become primarily a transit point for ships engaged in the slave trade between continental Africa and the Americas.

Depressing but important reading there…