1594 CE was a great year for the military-industrial complex both in Europe and worldwide. In East Asia, the Chinese and Koreans continued to battle Japan’s invasion of Korea. In Eastern Europe, the land war between the Habsburgs and the Ottomans continued…

Here were some other interesting things that were happening that year. I’ll start with Europe then go global.

Henry IV enters Paris, get crowned

This happened in March, and was a follow-on to his renunciation of Protestantism in 1593. France is still not particularly unified or capable of launching significant empire-building projects.

Anti-English rebellion in Ireland continues

I guess I should have put this into the 1593 listing, since that was the year that “Tyrone’s Rebellion” started in earnest in Ireland. This was a “Nine Years War” whose precise course seems complex to unravel, though the big theme was the resistance of the Irish indigenes to England’s continuing attempt to implant colonial settlements in the island. One of the leaders of the rebellion was Hugh O’Neill, who came from a powerful Irish sept (clan)– but he’d been brought up by a family inside the settlers’ “Pale” in Ireland, and the English authorities regarded him as “a reliable lord”– until they didn’t…

Of course, there was also a strong religious (Catholic-Protestant) religious component to the ongoing conflict in Ireland. Just as the English had provided a lot of help to the Protestant Netherlanders in their struggle against Spanish/Habsburg control, so the Spanish reciprocated by providing a lot of help to the Irish resistants.

West of Ireland leader Gráinne Ní Mháille plays the odds

Another super-interesting and very complex character on the Irish side was Grace O’Malley (c. 1530 – c. 1603), also known as Gráinne Ní Mháille, Gráinne O’Malley, Gráinne Mhaol, etc. She was the head of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland, described as a “Land-owner, sea-captain, and political activist.” She sounded like a tough defender of her lands and rights, who resisted the attempt by the (actually English) “Kingdom of Ireland” to impose its control over her lands. But was she?

In 1593, she had gone to see Queen Elizabeth in person. English-WP tells us how that went:

Ní Mháille refused to bow before Elizabeth because she didn’t recognise her as the “Queen of Ireland”. It’s also rumoured that she had a dagger concealed about her person, which guards found upon searching her. Elizabeth’s courtiers were said to be very upset and worried, but Ní Mháille informed the Queen that she carried it for her own safety. Elizabeth accepted this and seemed untroubled…

Their discussion was carried out in Latin, as Ní Mháille spoke no English and Queen Elizabeth I spoke no Irish. After much talk, the women came to an agreement that included that Elizabeth would remove Bingham [an English administrator who’d been bothering Ní Mháille] from his position in Ireland, and Ní Mháille would stop supporting the Irish lords’ rebellions.

Bingham was removed but several of Ní Mháille’s other demands (including the return of the cattle and land that Bingham had stolen from her) remained unmet, and soon Elizabeth sent Bingham back into Ireland. Bingham continued to plague Ní Mháille and in 1594 troops were quartered on her lands.

As the Nine Years’ War escalated, Ní Mháille sought to retrench her position with the crown. On 18 April 1595 she petitioned Lord Burghley, complaining of the activities of troops and asking to hold her estate for Elizabeth I. She added that ‘her sons, cousins, and followers will serve with a hundred men at their own charges at sea upon the coast of Ireland in Her Majesty’s wars upon all occasions…to continue dutiful unto Her Majesty, as true and faithful subjects’. Throughout the war she encouraged and supported her son Tibbot Burke to fight for the Crown against Tyrone’s confederation of Irish lords.

(The banner image above is an engraving of Gráinne Ní Mháille meeting Queen Elizabeth.)

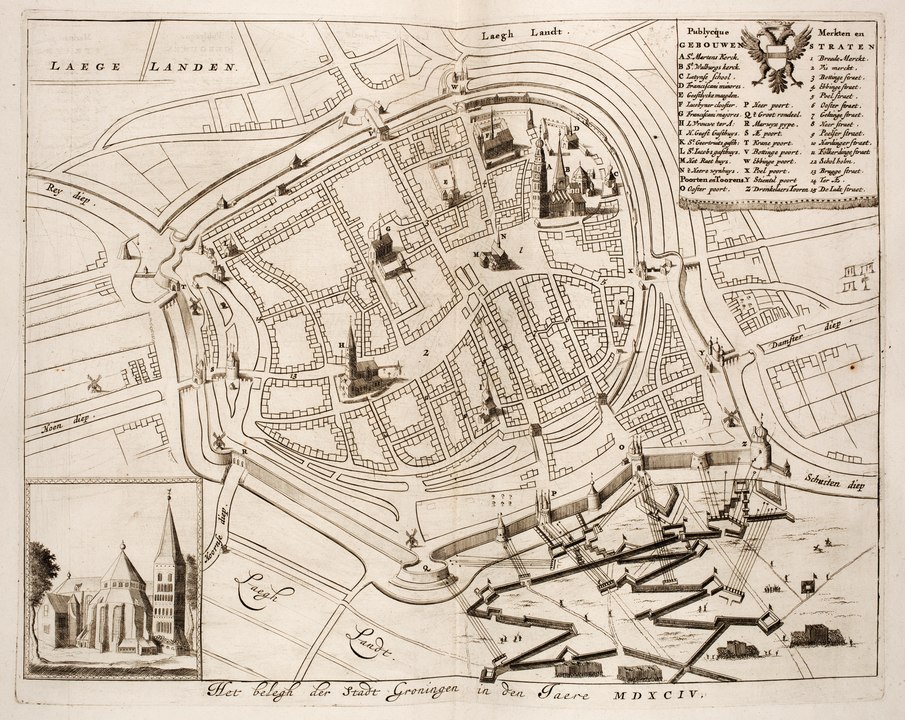

Dutch city of Groningen taken by the “United Provinces”

A joint UP-English force of 12,000 had been besieging the Spanish garrison in Groningen for two months when, on July 22, they managed to to capture it. This capture was decisive for the Dutch Republic as it pushed the last of the Spanish forces out of the Northern provinces.

The city was then merged with the surrounding district and the transition to the new Protestant regime was followed by the expulsion of all property of the Roman Catholics as well as a complete ban on Catholicism.

Dutch merchants form global trading company

Following on the (often extremely profitable) example set by their counterparts in London, in 1594 a group of nine Amsterdam merchants established a joint-stock company, the “Compagnie van Verre”, with the goal of breaking the extremely profitable monopoly Portugal had established on the import of pepper (and presumably, other spices) into Europe. The shareholders set about buying and equipping “three heavily armed ships and a pinnace” which would set sail in April 1595– following routes described by a guy called Jan Huygen van Lischoten who had lifted from the Portuguese the extremely valuable intellectual property regarding how to get most safely to, and in and out of, the key pepper-exporting ports of the East Indies.

That initial voyage would not be successful/profitable. But the merchants of Amsterdam were not deterred. In 1598 the Compagnie van Verre merged with the Nieuwe Compagnie and in 1597 with the Oude Compagnie. The resulting company then merged with the Nieuwe Brabantsche Compagnie in 1601 to form the Verenigde Amsterdamse Compagnie, which in 1602 merged with many other companies into the infamous Dutch East India Company (VOC), in whose chambers in Amsterdam it would retain its own room.

Philip applies the “encomienda” system to the Philippines

Here is, of course, a much more “mature” imperial system, Spain’s, which is now 102 years old…

As we can recall, the encomienda system was the system various Catholic monarchs had developed during the long slogging centuries of their “re-” conquista of Iberian lands from Muslim control, to enable them to both control and exploit the peasantry of the lands that they conquered. And a big part of that “control” was always mind-control, that is, the forced conversion of these to-be-exploited peasants to the Catholic faith, a task in which the Inquisition was a crucial tool.

After Ferdinand and Isabella made their first forays into the Caribbean and the Americas, extending the encomienda system there must have seemed a “natural” move, since basically the Catholic church had assured them it could– indeed should— be applied to all “Muslims or other heathens”.

The way the encomienda system worked was basically as a series of grants that the Spanish monarchs– or strictly speaking, in the case of the Americas and the Caribbean, the monarch of Castile– would give to well-favored Spanish individuals giving them the right to exploit (and convert to Catholicism, using as much force as they needed) all the peons within a given territory. Christopher Columbus established the encomienda system after his arrival and settlement on the island of Hispaniola requiring the natives to pay tributes or face brutal punishments. Tributes were required to be paid in gold… and the first great encomendero of “new Spain” (Mexico) had been Hernán Cortés.

And now, on June 11, 1594, Philip II enacted a law to extend this well-tried system to the Philippines. Here, there was a little bit of a wrinkle: these encomienda grants were made not to newly arrived Spanish conquistadors but to the local nobles (principalía).

This English-WP page tells us:

In order to implement a system of indirect rule in the Philippines, King Philip II ordered, through this law of 11 June 1594, that the honors and privileges of governing, which were previously enjoyed by the local royalty and nobility in formerly sovereign principalities who later accepted the catholic faith and became subject to him, should be retained and protected. He also ordered the Spanish governors in the Philippines to treat these native nobles well. The king further ordered that the natives should pay to these nobles the same respect that the inhabitants accorded to their local Lords before the conquest without prejudice to the things that pertain to the king himself or to the encomenderos.

The royal decree says: “It is not right that the Indian chiefs of Filipinas be in a worse condition after conversion; rather they should have such treatment that would gain their affection and keep them loyal, so that with the spiritual blessings that God has communicated to them by calling them to His true knowledge, the temporal blessings may be added, and they may live contentedly and comfortably. Therefore, we order the governors of those islands to show them good treatment and entrust them, in our name, with the government of the Indians, of whom they were formerly lords. In all else the governors shall see that the chiefs are benefited justly, and the Indians shall pay them something as a recognition, as they did during the period of their paganism, provided this is without prejudice to the tributes that are to be paid us, or to that which pertains to their encomenderos.”

Through this law, the local Filipino nobles (under the supervision of the Spanish colonial officials) became encomenderos (trustees) also of the King of Spain, who ruled the country indirectly through these nobles. Corollary to this provision, all existing doctrines and laws regarding the Indian caciques were extended to Filipino principales. Their domains became self‑ruled tributary barangays of the Spanish Empire.

The system of indirect government helped in the pacification of the rural areas, and institutionalized the rule and role of an upper class, referred to as the “principalía” or the “principales”, until the fall of the Spanish regime in the Philippines in 1898.

… By the end of the 16th century, any claim to Filipino royalty, nobility or hidalguía had disappeared into a homogenized, Hispanicized and Christianized nobility – the principalía.

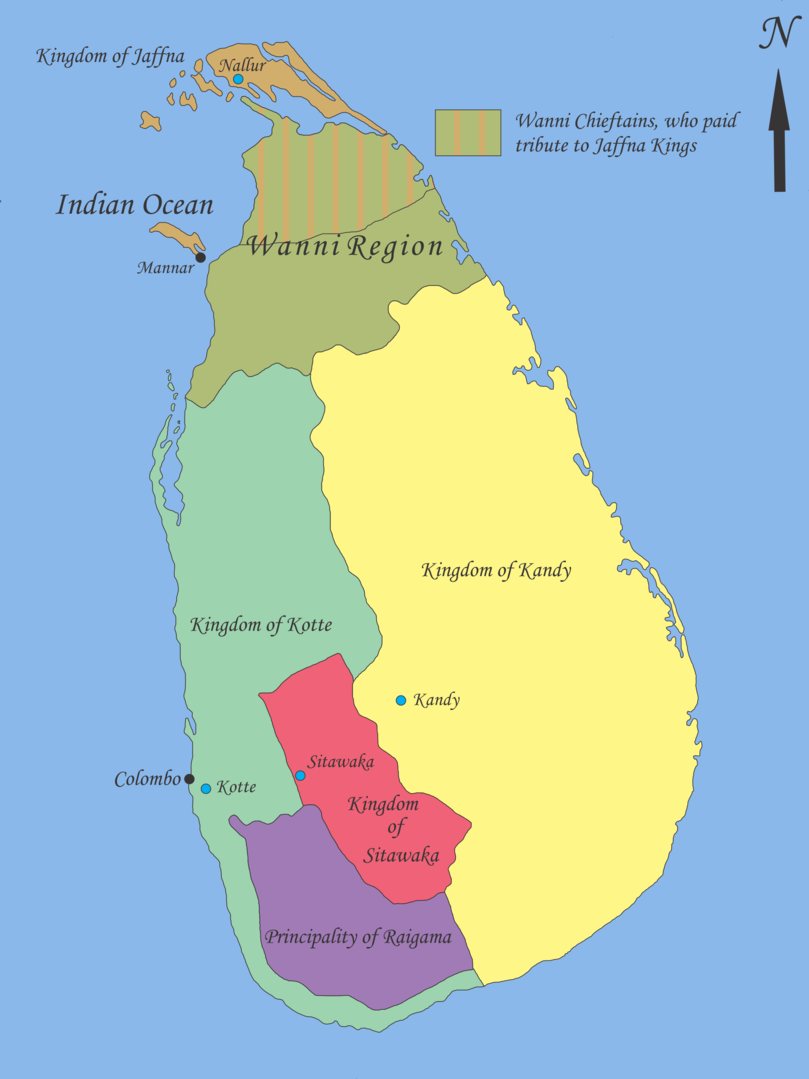

Portuguese defeated by Kandy

Three years earlier, Portuguese forces on today’s Sri Lanka had decisively defeated the Kingdom of Jaffna, in the north. Now, the only part of the island that remained unconquered by the Portuguese was Kandy, an offshoot of the previous Sitawaka Kingdom that occupied a large chunk of terrain on the east. The plan to conquer it was hatched by Francisco da Silva, captain of the fort at Colombo, and Pedro Lopes de Sousa, a guy with some experience of fighting in Sri Lanka: it centered on using a young, legitimate Kandyan princess whom the Portuguese called “Dona Catarina”, and who was under their control, to be the figurehead for their attack.

Sousa went to the Portuguese Viceregal Council in Goa and got permission to mount the campaign, which is known to Western historians as the Campaign of Danture, after the location of its final, decisive battle. Sousa apparently successfully demanded of the council that he (or a nephew of his? unclear… ) be allowed to marry Dona Catarina and that he be appointed “Captain-Major of the Field”. But the council stipulated that the marriage would be postponed until the Kingdom of Kandy was completely subjugated. “They further granted Sousa the title of General Conquistador, the first ever created in Ceylon, with the administrative title of Governor and the field rank of Captain-General.”

I guess all those titles came with budgets attached, so good for him…

On July 5, 1594, Sousa launched his invasion of Kandyan territory– from the west, across the Balana Pass. He commanded a force that included:

- ~ 1,000 Portuguese

- 15,400 Lascarins (conscripted indigenes)

- an unknown number of mercenraries and coolies, and

- 47 elephants.

They reached the stunningly located inland capital, Kandy, easily enough, bringing Dona Catarina in in a grand procession. “Captain-General Sousa, accompanied by Kandyan princes and chieftains, welcomed her at the city gates and escorted her into the Palace. Gold and silver coins were scattered in the streets for the inhabitants to gather. After three days she was crowned as Empress of Kandy in a large celebration attended by many people from the countryside, including local princes and nobles.”

The actual Kandyan King, Vimaladharmasuriya, had retreated before they got there, burning the palace as he left… and now, during he three days of festivities, his men entered the city at night disguised as beggars, setting fires all around the city. But that was not all. A chronicler called Phillipus Baldaeus wrote that: “Portugesche troops, they grew insolent and troublesome and committed various acts of depredation, such as plundering their [Kandyans’] property, ravishing their women and killing their children and those who opposed their will, and also setting fire to several of their villages …” And rumors that Dona Catarina was about to marry a Portuguese further fanned the flames of nationalist resistance.

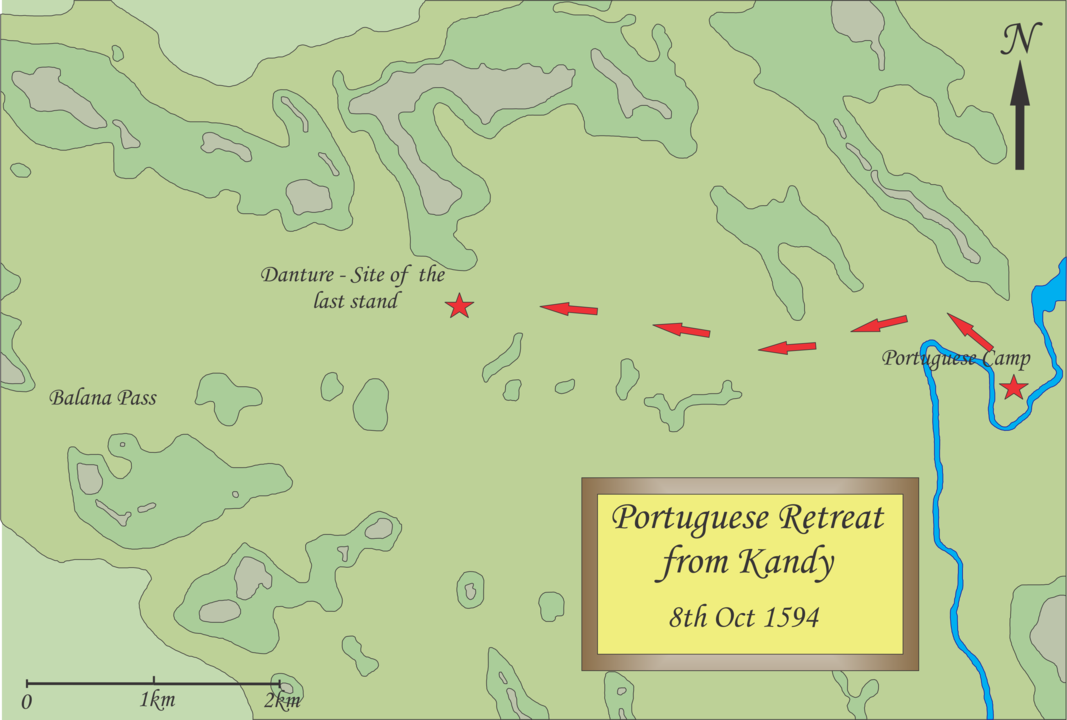

It was not going well for the Portuguese. Sousa sent out various expeditions to try to quell the resistance, but they failed. King Vimaladharmasuriya meanwhile also hatched a clever plot to sow extreme distrust between Sousa and one of his key Lascarin allies, a very well-respected guy called Jayavira. The plot succeeded brilliantly. A bunch of Sousa’s men killed Jayavira. “Soon word of Jayavira’s murder spread through the Lascarin camp. Shouts of Rajadore Jayavire marapue! (“King Jayavira is murdered!”) echoed from all directions and many Lascarins fled in panic to the Kandyans, along with the remaining Badaga mercenaries. By the morning of the following day most of the Lascarins, excepting those from Colombo and Mannar, had deserted.”

Things carried on getting worse and worse for the Portuguese. By early October it was all over.

Except for the handful that escaped or returned to Mannar with Captain Francisco, all of the 1000 Portuguese soldiers were killed or captured. In addition to the soldiers, six Franciscan priests died in the battle, including Fr. Simão de Liz and Fr. Manuel Pereira who were killed in the last stand. Only three soldiers are known to have escaped from the Battle of Danture… The exact numbers of Lascarin and Kandyan casualties are not known.

Then, this almost inevitable corollary: “Soon after the battle, King Vimaladharmasuriya married Dona Catarina with a festival that lasted for 110 days. He also granted lands, offices and titles to warriors who had distinguished themselves in the campaign. He began to reinforce the Balana pass with three new forts, which were to prove their effectiveness during the Balana Campaign in 1602.”

The political results were impressive:

Just before the Campaign of Danture, Kandy was a politically unstable state, ruled by a usurper with insignificant military power. After the battle, with his marriage to Dona Catarina, Vimaladharmasuriya’s claim to the throne was secured and marked the beginning of a new dynasty. The victory at Danture saved Kandy from subjugation by the Portuguese at a time when they had already conquered the rest of Sri Lanka; it remained an independent state till 1815, effectively resisting the Portuguese, Dutch and British.

The tactics the Kandyans used in this campaign served as a model for their future repeated successes against three major European powers. They had captured as spoils of war a large stock of Portuguese weapons and the treasure of Jayavira, further strengthening Kandy’s arsenal and its treasury.

This was the first time that a Portuguese army had been so completely defeated during their military operations in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese were determined to avenge the Kandyan victory, and in 1602, after many years of preparation, another army was to invade Kandy, under Dom Jerónimo de Azevedo. But the Kandyans would defeat them at Balana, leading to a desperate retreat across the country. After this setback, the Portuguese dropped any plans of capturing Kandy intact and Dom Jerónimo instead switched to a systematic campaign of raids, twice every year, using smaller detachments of troops, aimed at crops, cattle and villages, that ravaged Kandy in the coming years.