Omg, 1562 CE, the year of the first instance of officially-backed English involvement in the trans-Atlantic trade in enslaved Africans. (A few other globally significant things happened, too.)

Here goes:

- John Hawkins was a 30-year-old mariner from the southwest England port town of Plymouth, when this happened (per WP): “Hawkins received commission from Queen Elizabeth I which allowed him to privateer [Think: direct precursors of today’s military contractors… ] England was not at war with Spain, but the commission allowed Hawkins to plunder the Spanish fleet for loot. Hawkins formed a syndicate of wealthy merchants to invest in trade. In 1562, he set sail with three ships to Sierra Leone where he captured 300 slaves, and took them to the plantations in the Americas where he traded the slaves for pearls, hides, and sugar. The trade was so prosperous that on his return to England the Crown supported additional voyages and granted Hawkins a coat of arms which displays a male slave on it.” I have chosen not to display here either Hawkins’s disgusting coat of arms or his portrait. Scroll on down for more on Hawkins and his lengthy professional ties with Elizabeth. (The image above is a painting of a Liverpool ship of that era, most likely used to ship enslaved Africans.)

-

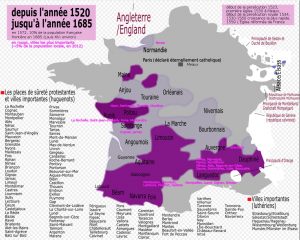

Today’s France during the Wars of Religion. Purple is Huguenot, gray Catholic, lilac, contested In early 1562, forces loyal to Catholic nobles undertook a massacre of Protestant Huguenots in the Champagne district of France that then sparked the first of seven or more “Wars of Religion” in France, which lasted until 1598. English-WP tells us: “It is estimated that three million people perished in this period from violence, famine, or disease in what is considered the second deadliest religious war in European history (surpassed only by the Thirty Years’ War [of the 17th century], which took eight million lives).” As we have already seen, England, whose governance was now solidly Protestant, and Spain (Catholic) were both deeply involved in these internal conflicts inside France. In September, Queen Elizabth signed the Treaty of Hampton Court with Huguenot leader Louis, Prince of Condé, promising to aid him; and the following month an English force was landed in Le Havre.

- During this prolonged period of intra-Christian religious turmoil inside continental Europe, one “solution” increasingly considered by many religious dissidents– often with the blessing of the powers-that-be (were)– was to emigrate overseas to become settlers in the Americas. So in 1562, we also see the first attempt by French Huguenots to establish a religion-based in North America!

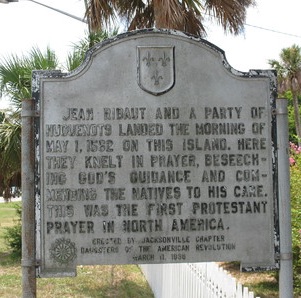

Marker commemorating Ribault’s first landfall in Florida This project was undertaken by Jean Ribault, who led an expedition of some 150 colonists that, after first landing in Florida, then headed north and founded their settlement he called Charlesfort on Parris Island in present-day South Carolina. Later in the year he sailed back home, only to discover the First War of Religion had broken out in his absence. So he went to London, got an audience with QE-1, and starting seeking funding/backing for a return voyage to Charlesfort. But he was imprisoned as a spy. The next year, he was released and allowed to return to France to continue seeking backers there. Meantime, over in Charlesfort things had not gone well: mutinies, fires, etc. (Almost certainly also some native resistance?) The remaining colonists built a makeshift boat to return home in but most of them perished on the voyage.

Whoa, and meanwhile over in the Indian Ocean Portugal’s well-armed and generally well-organized adventurers were being dealt a big setback in present-day Sri Lanka. This was in the Battle of Mulleriyawa,part of the much more protracted Sinhalese-Portuguese War of 1527-1658. The Portuguese had had a (well-armed) trading presence in Colombo since 1505. That was near-ish to the seat of the Kingdom of Kotte and not far from the Kingdom of Sitawaka, with which Kotte was in conflict. It was a long story. (and almost certainly the telling of it on the English-WP page has been highly contested!) The Portuguese were backing Kotte’s ruler, and some of the fiercely fought battles involved elephants, horses, and Portuguese fighters forced to use their muskets as clubs… English-WP tells us: “This was one of the few pitched battles between the Portuguese and the Sinhalese. The Portuguese became extremely weak within their area and the threat to Sitawaka from this direction ceased. Emboldened by this victory, [the Sitawaka leaders] conducted frequent attacks against the Portuguese and the Kotte Kingdom.By 1565 the Portuguese were unable to hold the capital city of Kotte. They abandoned Kotte and moved to Colombo (which was guarded by a powerful fort and the Portuguese navy) with their puppet King Dharmapala. “

Whoa, and meanwhile over in the Indian Ocean Portugal’s well-armed and generally well-organized adventurers were being dealt a big setback in present-day Sri Lanka. This was in the Battle of Mulleriyawa,part of the much more protracted Sinhalese-Portuguese War of 1527-1658. The Portuguese had had a (well-armed) trading presence in Colombo since 1505. That was near-ish to the seat of the Kingdom of Kotte and not far from the Kingdom of Sitawaka, with which Kotte was in conflict. It was a long story. (and almost certainly the telling of it on the English-WP page has been highly contested!) The Portuguese were backing Kotte’s ruler, and some of the fiercely fought battles involved elephants, horses, and Portuguese fighters forced to use their muskets as clubs… English-WP tells us: “This was one of the few pitched battles between the Portuguese and the Sinhalese. The Portuguese became extremely weak within their area and the threat to Sitawaka from this direction ceased. Emboldened by this victory, [the Sitawaka leaders] conducted frequent attacks against the Portuguese and the Kotte Kingdom.By 1565 the Portuguese were unable to hold the capital city of Kotte. They abandoned Kotte and moved to Colombo (which was guarded by a powerful fort and the Portuguese navy) with their puppet King Dharmapala. “- Also this year, the Spanish-born Catholic Bishop of the Yucatan Diego de Landa, pushed forward his actions under the Inquisition and burned “a disputed number of Maya codices (according to Landa, 27 books) and approximately 5000 Maya cult images… Only three pre-Columbian books of Maya hieroglyphics (also known as a codex) and, perhaps, fragments of a fourth are known to have survived.” Under Landa’s Inquisition, “Scores of Maya nobles were jailed pending interrogation, and large numbers of Maya nobles and commoners were subjected to examination under ‘hoisting.’ During hoisting, a victim’s hands were bound and looped over an extended line that was then raised until the victim’s entire body was suspended in the air. Often, stone weights were added to the ankles or lashes applied to the back during interrogation. During his later trial for his actions, Landa vehemently denied that any deaths or injuries directly resulted from these procedures.”

More on John Hawkins

English-WP tells us: “He styled himself ‘captain general’ as the general of both his own flotilla of ships and those of the English Royal Navy, and to distinguish himself from those Admirals that served only in the administrative sense and were not military in nature. ” Actually, he seems to have shifted fairly easily between being a private government contractor and being a government official– like so many in the U.S. empire today.

During the early years of his engagement in the shipping and trading of enslaved Africans, Hawkins was operating as a Crown-licensed “privateer.” His very first (1562) slaving voyage took the enslaved Africans from what was described as “Guinea” to the Spanish-controlled island of Hispaniola– today’s DR and Haiti.) The Spanish colonists there came to rely on his supplies because (a) they had already worked most of Indigenes of the island to death through their use of the encomienda system of enslavement of the locals, and (b) the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas prohibited them from sailing to anywhere in Africa. The Spanish (both sides of the Atlantic) liked to keep a monopoly on all the trade they engaged in; but Hawkins was allowed to trade with them on payment of 7.5% tax.

This interesting page about Hawkins on the website of the Royal Museums Greenwich has a very short, and not perfect, video about his early life in which the narrator says that after he explained to Queen Elizabeth how his slave-trading project would work, “she was initially appalled by the idea, wondering what would become of the Africans and what would become of their souls. When Sir John explained the profits to her, her morals went to one side“, and she provided her support for the project.

The RMG web-page has a short explanation of the role of the (Crown-backed) privateers and a little about the role Hawkins played later in his life as Treasurer of the Royal Navy. From a quick reading about him my first impression is that he started out as a sort of freewheeling government contractor, doing not just slave-trading but also some harassing and looting of the large ship convoys on which the Spanish were hauling back to the motherland the gold, silver, and other booty they were looting from Americas. Eventually, the Spanish got really riled, and 26 years later they would seek to end the English harassment once and for all by overpowering England with their Spanish Armada. But by then, guess what, Hawkins had long slipped back into his role as a government official and had built and equipped the now much more capable English Navy.

Anyway, in all the seas we’ve looked at so far, the distinction between pirates, privateers, and “legit” (and also usually well-armed) trading ships is a very slippery one…