1689 was another big year in the (always violent) development of the 4.5 globe-circling empires whose home-countries lined the mid-Atlantic coast of Europe. The “0.5” there is France, whose aspirations to build a globe-circling empire have not yet been as well fulfilled as those of the “Big Four”, namely Portugal, Spain, England, and the Dutch United Provinces. But though France was the weakling among these powers at the global level, on the home continent of Europe it had emerged over the preceding 10-15 years as the single most powerful actor, one that controlled a relatively large chunk of real estate that was helpfully located to have both an Atlantic and a Mediterranean coast (and to be able to cut off Spain from contact with central and northern Europe.) And for some decades now, France had had a monarch with ambition and an iron nerve who had gathered around himself groups of competent advisors who shared his vision of creating an effective, unified administration for all his kingdom– and hopefully, also, some profitable colonial opportunities overseas, though their prime focus was still on amassing power in Europe.

So guess what had happened in 1688? All the other four European colonial powers ganged up together to wage war against France… That war would continue for nine years, and its effects would be felt in distant North America, as well as in Europe. In 1689, the anti-France coalition became formalized into a “Grand Alliance”, or the “League of Augsburg.” Oh, and along the way, in April 1689 the Stadholder of Holland got himself and his wife crowned as King William and Queen Mary of England.

So there’s a lot to write about today. Let me take it in this order:

- A quick intro to the Nine Years’ War in Europe

- Its extension in North America

- The Iroquois’s (separate) revenge against the French colonists

- Other news from North America

- Continuing fall-out from James’s toppling, in England and Ireland

- Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb hires himself a fleet

- Tsar Peter, aspiring to greatness, designs a road

- Figures on the numbers of enslaved persons transported and sold by England’s Royal African Corporation

A quick intro to the Nine Years’ War in Europe

English-Wikipedia tells us this:

The Nine Years’ War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg Monarchy), the Dutch Republic, England, Spain, Savoy and Portugal. It was fought in Europe and the surrounding seas, in North America, and in India. It is sometimes considered the first global war. The conflict encompassed the Williamite war in Ireland and Jacobite risings in Scotland, where William III and James II struggled for control… and a campaign in colonial North America between French and English settlers and their respective Indigenous allies.

Louis XIV of France had emerged from the Franco-Dutch War in 1678 as the most powerful monarch in Europe… Louis XIV’s decision to cross the Rhine in September 1688 was designed to extend his influence and pressure the Holy Roman Empire into accepting his territorial and dynastic claims. However, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I and German princes resolved to resist. The States General of the Netherlands and William III brought the Dutch and English into the conflict against France and were soon joined by other states, which now meant the French king faced a powerful coalition aimed at curtailing his ambitions.

The main fighting took place around France’s borders in the Spanish Netherlands, the Rhineland, the Duchy of Savoy, and Catalonia. The fighting generally favoured Louis XIV’s armies, but by 1696 his country was in the grip of an economic crisis. The Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) were also financially exhausted, and when Savoy defected from the Alliance, all parties were keen to negotiate a settlement…

Its extension in North America

You will recall that just a few years ago, French explorers had laid a claim to, essentially, the whole of the Mississippi River valley and watershed, connecting the French trading colonies around the Great Lakes with the very small and vulnerable presence they were able to establish near the Mississippi Delta, on the Gulf of Mexico. By staking that claim, they were constraining the ability of the English colonists perched on the Atlantic coast of North America to move fully westward across the continent; and already in the northern reaches of the English-French colonial territories in North America, the colonists of the two empires had been clashing quite a lot.

England’s deposed King James had fled first to France and, in Ireland, had started to receive some French military help… So it was not surprising that in N. America, the news of his deposing in 1688 had spurred the outbreak of yet another round of English-French fighting. This is what this page on WP tells us about it:

King William’s War (1688–1697, also known as the Second Indian War… was the North American theater of the Nine Years’ War (1688–1697)… For King William’s War, neither England nor France thought of weakening their position in Europe to support the war effort in North America. New France and the Wabanaki Confederacy were able to thwart New England expansion into Acadia, whose border New France defined as the Kennebec River in southern Maine…

The war was largely caused by the fact that the treaties and agreements that were reached at the end of [Metacomet’s Uprising, aka as King Philip’s War] (1675–1678) were not adhered to. In addition, the English were alarmed that the Indians were receiving French or maybe Dutch aid. The Indians preyed on the English and their fears, by making it look as though they were with the French. The French were played as well, as they thought the Indians were working with the English. These occurrences, in addition to the fact that the English perceived the Indians as their subjects, despite the Indians’ unwillingness to submit, eventually led to two conflicts, one of which was King William’s War.

(I love that wording of the Indians “preying on” the poor hapless English “by making it look as though they were with the French.” Instead of saying “preying on”, how about saying something like “The Indigenous peoples, who by now had acquired long experience of dealing with these heavily armed and violent interlopers from a distant continent, had figured out several ways of trying to play the different European tribes and bands off against each other… “)

The Iroquois’s (separate) revenge against the French colonists

This was a series of conflicts that had been going on for decades: between the French colonists and the various components of the Iroquois Confederacy… It was often called the “Beaver Wars”.

So from this page on WP I learned this about a series of developments in the BeaverLeisl Wars that occurred in the 1680s, including in 1689:

… With the renewal of hostilities, the militia of New France was strengthened after 1683 by a small force of regular French navy troops in the Compagnies Franches de la Marine… In June 1687, Governor Denonville and Pierre de Troyes set out with a well organized force to Fort Frontenac [built at the mouth of the Cataraqui River where the St. Lawrence River leaves Lake Ontario], where they met with the 50 sachems of the Iroquois Confederacy from their Onondaga council. These 50 chiefs constituted the top leaders of the Iroquois, and Denonville captured them and shipped them to Marseilles, France to be galley slaves. He then travelled down the shore of Lake Ontario and built Fort Denonville at the site where the Niagara River meets Lake Ontario…

The Iroquois retaliated by destroying farmsteads and slaughtering entire families. They burned Lachine to the ground on August 4, 1689.

Lachine was a small colonial settlement to the southwest of Montreal. This other page on WP adds a couple of other details.

First, though it said nothing about the capture, enslaving, and transportation of the Iroquois sachems, it did add this information: “Denonville’s 1687 invasion of the Seneca nation country destroyed approximately 1,200,000 bushels of corn and crippled the Iroquois economy.”

Then, these details of the anti-colonial action against Lachine:

On the rainy morning of August 5, 1689, Iroquois warriors used surprise to launch their nighttime raid against the undefended settlement of Lachine. They traveled up the Saint Lawrence River by boat, crossed Lake Saint-Louis, and landed on the south shore of the Island of Montreal. While the colonists slept, the invaders surrounded their homes and waited for their leader to signal when the attack should begin. They attacked the homes, broke down doors and windows, and dragged the colonists outside, where many were killed. When some of the colonists barricaded themselves within the village’s structures, the attackers set fire to the buildings and waited for the settlers to flee the flames.

The colonists’ casualties have been reported by different sources as ranging from 24 killed to 250 killed.

This did not look good on Gov. Denonville’s resume. He was speedily eased out, and a previous governor, the Comte de Frontenac was brought in for the next nine years. This WP page on Danonville tells us this:

Frontenac… realized the true danger the imprisonment of the sachems created. He located the 13 surviving leaders, and they returned with him to New France in October 1698.

When Denonville had returned to France, the king continued to show his confidence in [him] by appointing him a tutor to the children of the royal household.

Other news from North America

Lots going on in North America in 1689! Everything points to these still-young colonies that the French and English had there being very violent places. The colonies had been established and were maintained, after all, only by the continued use or threat of the use of force against the Indigenes; and “might makes right” pervaded many aspects of the colonists’ lives. So in 1689 there were two violent revolts in the English colonies: one in Boston and one in New York.

Here’s the short version on what happened in Boston, which still had a very strong Puritan component:

The 1689 Boston revolt was a popular uprising on April 18, 1689 against the rule of Sir Edmund Andros, the governor of the Dominion of New England. A well-organized “mob” of provincial militia and citizens formed in the town of Boston, the capital of the dominion, and arrested dominion officials. Members of the Church of England were also taken into custody if they were believed to sympathize with the administration of the dominion. Neither faction sustained casualties during the revolt. Leaders of the former Massachusetts Bay Colony then reclaimed control of the government. In other colonies, members of governments displaced by the dominion were returned to power.

Andros… had earned the enmity of the local populace by enforcing the restrictive Navigation Acts, denying the validity of existing land titles, restricting town meetings, and appointing unpopular regular officers to lead colonial militia, among other actions. Furthermore, he had infuriated Puritans in Boston by promoting the Church of England, which was rejected by many nonconformist [that is, Protestant but not C of E] New England colonists.

What happened in New York was a much more serious breakdown of law and order. That colony did not have the strong Puritan underpinning that New England had but had been established first of all by armed Dutch merchants and then handed over to the English– or more specifically, to the former King James when he was still James, Duke of York, the head of the English military. But basically, it was just an extractive, money-making kind of place. (Then and now.)

In 1688, King James had deputed an English army captain called Francis Nicholson to administer New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey as the territories’ lieutenant governor. But like all the colonies, New York already had a citizen-based militia, which was sometimes (as in London) called a “trained band”. WP tells us here what happened in 1689:

New York’s defenses were in poor condition, and Nicholson’s council voted to impose import duties to improve them. This action was met with immediate resistance, with a number of merchants refusing to pay the duty. One in particular was Jacob Leisler, a German-born Calvinist merchant and militia captain. Leisler was a vocal opponent of the dominion regime, which he saw as an attempt to impose popery on the province, and he may have played a role in subverting Nicholson’s regulars.

On May 22, Nicholson’s council was petitioned by the militia, who sought more rapid improvement to the city’s defenses and also wanted access to the powder magazine in the fort. This latter request was denied, heightening concerns that the city had inadequate powder supplies. This concern was further exacerbated when city leaders began hunting through the city for additional supplies.

Nicholson made an intemperate remark to a militia officer on May 30, 1689, and the incident flared into open rebellion. Nicholson was well known for his temper, and he told the officer, “I rather would see the Towne on fire than to be commanded by you”. Rumors flew around the town that Nicholson was prepared to burn it down. He summoned the officer and demanded that he surrender his commission. Abraham de Peyster was the officer’s commander and one of the wealthiest men in the city, and he engaged in a heated argument with Nicholson, after which de Peyster and his brother Johannis, also a militia captain, stormed out of the council chamber.

The militia was called out and descended en masse to Fort James, which they occupied. An officer was sent to the council to demand the keys to the powder magazine, which Nicholson eventually surrendered to “hinder and prevent bloodshed and further mischiefe”. The following day, a council of militia officers called on Jacob Leisler to take command of the city militia. He did so, and the rebels issued a declaration that they would hold the fort on behalf of the new monarchs until they sent a properly accredited governor…

At this point, the militia controlled the fort which gave them control over the harbor. When ships arrived in the harbor, they brought passengers and captains directly to the fort, cutting off outside communications to Nicholson and his council. On June 6, Nicholson decided to leave for England and began gathering depositions for use in proceedings there.

Leisler (who seems to have had connections with, or at least sympathies for, the French Huguenots) then set about extending and consolidating his power in the colony of New York. It wasn’t until early 1691 that the distant King William was able to send another governor for New York. Leisler’s page on WP takes up the tale:

On January 28, 1691, English Major Richard Ingoldesby, who had been commissioned lieutenant-governor of the province, landed with two companies of soldiers in Manhattan and demanded possession of Fort James. Leisler refused to surrender the fort without an order from the king or the governor. After some controversy, Ingoldesby attacked the fort on 17 March during which Leisler’s forces killed two of his soldiers and wounded several.

When Governor Sloughter finally arrived in New York the following March, he immediately demanded Leisler’s surrender. Leisler refused to surrender the fort until he was convinced of Sloughter’s identity, and the governor had sworn in his council. As soon as the latter event occurred, he wrote the governor a letter resigning his command.

Sloughter responded by arresting Leisler and nine of his colleagues, including his son-in-law Jacob Milborne. All but Milborne were released after trial. Leisler was imprisoned and charged with treason and murder. Shortly afterward, he was tried and condemned to death. His son-in-law and secretary, Milborne, was condemned on the same charges. Leisler’s son and other supporters were outraged by the trials, as they were considered unjust. The judges were the personal and political enemies of the prisoners, and their acts were described as “gross.”

Governor Sloughter was said to have hesitated to sign the death warrants but was trying to stabilize politics in the colony and did not have sufficient influence among the elite of New York City. He was said to have finally signed the warrants under the influence of wine.

On 16 May 1691, Leisler and Milborne were executed.The court had sentenced them to be hanged “by the Neck and being Alive their bodyes be Cutt downe to Earth and Their Bowells to be taken out and they being Alive, burnt before their faces….” (In fact, the real villain, Robert Livingston, later bragged in writing that the pair were spared the disemboweling and were cut down before dead and decapitated by sword. The crowd then began fighting over their heads to acquire hair as a souvenir.) By the English law of treason, their estates were forfeited to the Crown. Leisler’s son and other supporters appealed for justice from the committee of the Privy Council. It reported that although the trial was in conformity to the forms of law, they recommended the restoration of the estates to their heirs.

In 1695, by an Act of Parliament, achieved through the efforts of Leisler’s son and supporters, the names of Jacob Leisler and Milborne were cleared, and Leisler’s estate was restored to his heirs. Three years later the Earl of Bellomont, who had been one of the most influential supporters of Leisler’s son, was appointed as governor of New York. Through his influence, the assembly voted an indemnity to Leisler’s heirs.

By the way the banner image above is a detail from an engraving of people signing Jacob Leisler’s Declaration in New York.

Continuing fall-out from James’s toppling, in England and Ireland

In 1689, as they made the plans for their April coronation in London, William and Mary were also busy trying to strengthen political support for their rule. This portion on WP’s William III page summarizes some of the steps they took:

William encouraged the passage of the Toleration Act 1689, which guaranteed religious toleration to Protestant nonconformists. It did not, however, extend toleration as far as he wished, still restricting the religious liberty of Roman Catholics, non-trinitarians, and those of non-Christian faiths. In December 1689, one of the most important constitutional documents in English history, the Bill of Rights, was passed. The Act, which restated and confirmed many provisions of the earlier Declaration of Right, established restrictions on the royal prerogative. It provided, amongst other things, that the Sovereign could not suspend laws passed by Parliament, levy taxes without parliamentary consent, infringe the right to petition, raise a standing army during peacetime without parliamentary consent, deny the right to bear arms to Protestant subjects, unduly interfere with parliamentary elections, punish members of either House of Parliament for anything said during debates, require excessive bail or inflict cruel and unusual punishments. William was opposed to the imposition of such constraints, but he chose not to engage in a conflict with Parliament and agreed to abide by the statute.

The Bill of Rights also settled the question of succession to the Crown. After the death of either William or Mary, the other would continue to reign. Next in the line of succession was Mary II’s sister, Anne, and her issue, followed by any children William might have had by a subsequent marriage. Roman Catholics, as well as those who married Catholics, were excluded.

Ireland was controlled by Roman Catholics loyal to James, and Franco-Irish Jacobites [supporters of James] arrived from France with French forces in March 1689 to join the war in Ireland and contest Protestant resistance at the siege of Derry. William sent his navy to the city in July, and his army landed in August. After progress stalled, William personally intervened to lead his armies to victory over James at the Battle of the Boyne on 1 July 1690, after which James fled back to France.

Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb hires himself a fleet

You will recall that 1686 was the year the Director of the English East India Company directed his people to impose the EIC’s will on the Mughal Empire by force (and he got a fleet from the English Navy to help them do this.) 1688 and 1689 saw some notable developments in the war that ensued, which raged around virtually the whole coast of India.

WP tells us here about these:

In 1688, an English fleet was dispatched to blockade the Mughal harbours in the Arabian Sea on the western coast of India. Merchantmen containing Muslim pilgrims to Mecca (as part of the hajj) were among those captured. Upon hearing of the blockade, Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir decided to resume negotiations with the English.However, the Company sent out reinforcements commanded by Captain Heath who on his arrival disallowed the treaty then pending and proceeded to Balasore which he bombarded unsuccessfully. He then sailed to Chittagong; but finding the fortifications stronger than he had anticipated, landed at Madras.

After that Emperor Aurangzeb issued orders for the occupation of the East India Company possessions all over the subcontinent, and the confiscation of their property. As a result, possessions of East India Company were reduced to the fortified towns of Madras and Bombay.

In 1689, the strong Mughal fleet from Janjira commanded by the Sidi Yaqub and manned by Mappila from Ethiopian Empire blockaded the East India Company fort in Bombay, Fort William…

A “strong Mughal fleet”? We’ve never seen one of those before! The Mughals, remember, had come out of present-day Afghanistan and had slowly conquered almost the whole of the Indian land-mass– but they had never had any significant naval power, and that had left them very vulnerable to the heavily armed trading/raiding navies of first the Portuguese, and now the Dutch and English (and to a much lesser extent, the French.) Who was this Sidi Yakub?

This page on WP tells us more:

Qasim Yakut Khan also known as Yakut Shaikhji, Yakub Khan and Sidi Yaqub was a naval Admiral and administrator of Janjira Fort [located on an island a little way south of Bombay/Mumbai.]

He was born into a Koli family… He was jailed at a young age and later grew up in a Siddi Muslim family. There, he got his new name as Qasim Khan and after becoming admiral of the Mughal navy, he was titled Yakut Khan by Emperor Alamgir [aka Aurangzeb].

In 1689, the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb ordered Khan to attack Bombay for the third time after Indian vessels sailing to Surat were captured in 1686… In April 1689, the strong Mughal fleet from Janjira commanded by the Sidi Yaqub and manned by Mappila and Abyssinians laid siege to the British fortification to the south.

After a year of resistance, the English surrendered, and in 1690 the British governor Sir John Child [no relation to Josiah Child] appealed to Aurangzeb. In February 1690, the Mughals agreed to halt the attack in return for 150,000 rupees (over a billion USD at 2008 conversion rates) and Child’s dismissal. Child’s untimely death in 1690 however, resulted in him escaping the ignominy of being sacked.

Enraged at the agreement, he [I think this is Sidi Yaqub?] withdrew his forces on 8 June 1690 after razing the Mazagaon Fort.

I’ve never seen any other reference to the Mughals having a naval force, and it seems this one was acting principally as hired hands.

“Janjira” by the way is thought to be a version of the Arabic word “Jazeera”, meaning an island. The WP page about it is really interesting.

Tsar Peter, aspiring to greatness, designs a road

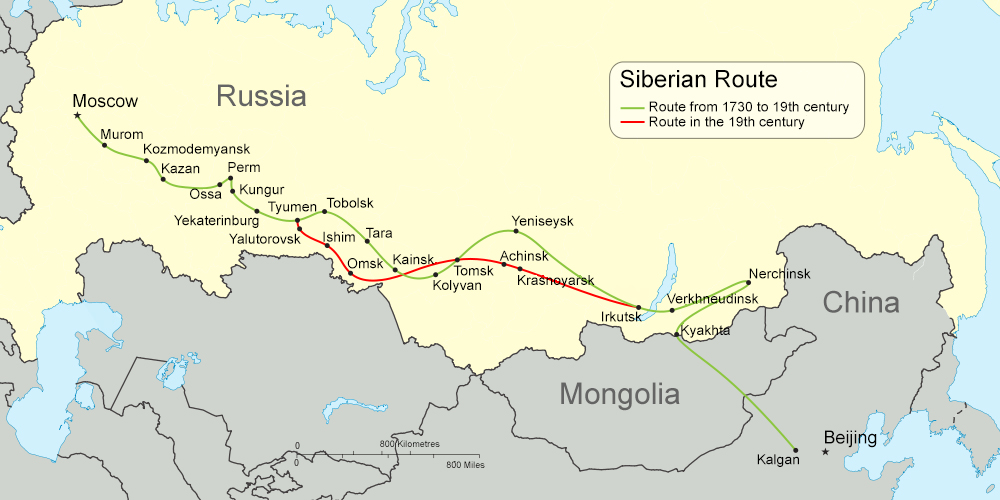

I think when we last left Russia’s Tsar Peter, he was still a boy; he was forced to rule alongside one of his sisters; and an older half-sister would hidden behind the two-seat throne and tell the boy what to say… Well, I guess he is now 17, and in 1689 he launches his very own “Belt and Road Initiative.” Well, a project for a Siberian Road, anyway. It took many decades to complete, but here’s a map of it:

And here’s a map of the web of riverine routes that had preceded it:

Figures on the numbers of enslaved persons transported and sold by England’s Royal African Corporation

And finally, lest we forget that King James II had been the president of the slavetrading Royal African Corporation along with all his other brutally exploitative, and profitable positions in England’s developing empire, we can note that 1689 saw yet another reorganization/re-capitalizing of the RAC that required that a decent set of accounts be presented to London’s investing public. In his book The Slave Trade, Hugh Thomas noted (pp.202-03) that “By the end of the seventeenth century, as much as three-fifth income of the RAC derived from the sale of slaves. (The other two-fifths being gold from Senegambia and the Gold Coast; camwood and beeswax from Sierra Leone; and gum, used for textiles, from the Senegal Valley.)

He also gave these figures (p.203):