Lots happening in 1690 CE! All the above-listed items, plus the founding of Barclays Bank (which merits a short notice here, for reasons that will become clear.)

First, let’s go to India.

EIC grovels to Aurangzeb, founds Calcutta

In yesterday’s post, I noted that the intervention of the local Muslim navy that Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb had hired to take on the English East India Company (EIC), had done so successfully, forcing the EIC to its knees. Well, literally so, according to this French engraving that showed EIC head Josiah Child groveling before Aurangzeb and begging his forgiveness:

That was actually more likely to have been the EIC’s chief in-country chief, John Child, no relation; and of course, the French were extremely gleeful to see the English thus humiliated…

In his 2019 book The Anarchy, William Dalrymple wrote that in the aftermath of “this fiasco”, a young regional factor (*regional rep) called Job Charnock founded a new British base in Bengal, “on the swampy ground between the villages of Kalikata and Sutanuti, adjacent to a small Armenian trading station, and with a Portuguese one just across the river.” (p.25) That later became Calcutta.

I believe that on this occasion there was no attempt to fortify or arm the base. When the EIC had tried to do that in 1686, that had provoked the whole just-ended war.

Dalrymple noted that the swampy location of the new trading station was not salubrious (pp.23-24):

Within a year of the founding of the English settlement at Calcutta, there were 1,000 living in the settlement but already… 460 names in the burial book…

Only one thing kept the settlement going: Bengal was ‘the finest and most fruitful country in the world’, according to the French traveller Francois Bernier. It was one of ‘the richest most populous and best cultivated countries’, agreed the Scot Alexander Dow. With its myriad weavers– 25,000 in Dhaka alone– and unrivalled luxury textile production of silks and woven muslins of fabulous delicacy…

The company existed to make money, and Bengal, they soon realised, was the best place to do it.

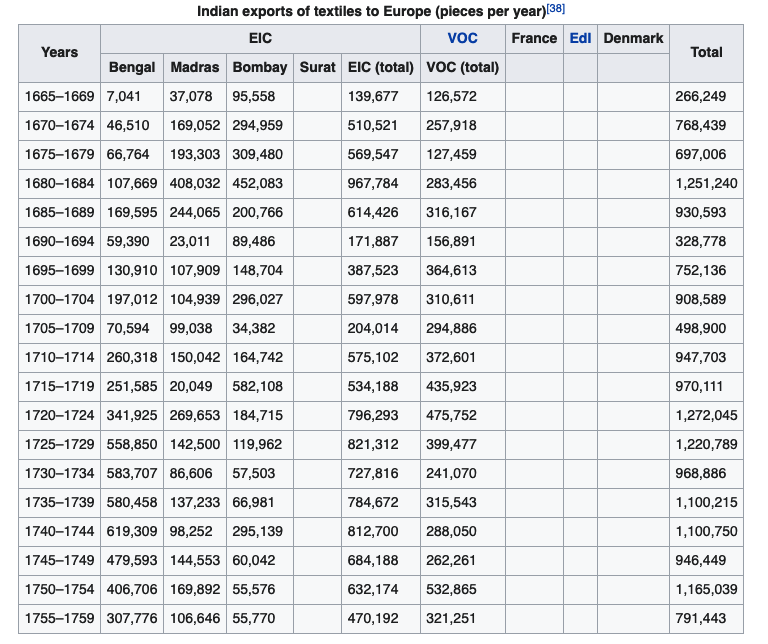

These figures, cited in the English-Wikipedia page on the EIC, give some insight into the rise of Bengal as a source for European textile imports:

French Navy wins in English Channel while William off in Ireland

I had mentioned a little yesterday about England’s deposed King James having snuck back over to Ireland to try to raise a (basically Catholic) rebellion against King William from there, and the fact that at the Battle of the Boyne in July 1690, William’s army had defeated James’s. This event certainly deserves a little more notice because during that battle each of these political leaders was actually commanding his own army. It proved to be the decisive setback for James’s hopes of staging a restoration to the English throne. And finally, the Protestant victory there proved a longlasting source of pride and community identity for Protestants in Ireland, nearly all of whom had come there as English-backed colonial settlers over the preceding decades.

This WP page on the Battle of the Boyne tells us this about the two men as commanders:

James was a seasoned officer who had proved his bravery when fighting in Europe,notably at the Battle of the Dunes. However, recent historians have suggested that he was prone to panicking under pressure and making rash decisions, which it has been suggested may have been due to poor health associated with the Stuart line.

William, although a seasoned commander, had yet to win a major battle. William’s success against the French had been reliant upon tactical manoeuvres and good diplomacy rather than force. His diplomacy had assembled the League of Augsburg, a multi-national coalition formed to resist French aggression in Europe. From William’s point of view, his taking power in England and the ensuing campaign in Ireland was just another front in the war against France in general, and Louis XIV in particular.

Anyway, long story short, William’s army won, and the casualties on each side were mercifully low by the standards of the time.

But while William was over there leading his forces in battle, back in the English Channel that separates England and France, William’s French nemesis Louis XIV was preparing a large naval force to try to seize the maritime initiative from the Anglo-Dutch force that generally prevailed in the Channel.

The English fleet there was commanded by the Earl of Torrington, a staunchly pro-William commander who was the First Lord of the Admiralty. On July 5, Torrington saw the French fleet assembling near the Isle of Wight and judging it foolish to engage with such a large force, announced his intention to retreat to the Straits of Dover.

William was off in Ireland. So WP tells us that this happened:

In William’s absence, Queen Mary and her advisors – the ‘Council of Nine’ – hastened to take measures for the defence of the country. Carmarthen thought that it was advisable to fight, as did Nottingham and Admiral Russell, who were unconvinced that the French were as strong as Torrington reported and considered that only the admiral’s pessimism, defeatism or treachery could account for his reports. As the two fleets moved slowly up the channel (with Torrington keeping carefully out of range), Russell drafted the order to fight. Countersigned by Nottingham, the orders reached the admiral on 9 July whilst he was off Beachy Head. Torrington realised that not to give battle was to be guilty of direct disobedience; to give battle was, in his judgment, to incur serious risk of defeat. Torrington called a council of war with his flag-officers, who concluded that they had no option but to obey.

So near the feature known as Beachy Head he prepared the English and Dutch ships in his fleet for the battle that ensued.

WP tells us this:

The eight-hour battle was a victory for the French but far from decisive. When the tide changed at 21:00, the Allies weighed anchor. Tourville pursued, but instead of ordering a general chase, he maintained the strict line-of-battle, reducing the speed of the fleet to that of the slower ships.Torrington burnt six more badly-damaged Dutch ships… and one English ship (the third rate 70-gun Anne) to avoid their capture before gaining the refuge of the Thames. The Wapen van Utrecht sank by herself. As soon as Torrington was in the safety of the river, he ordered all the navigation buoys removed, making any attempt to follow him too dangerous.

The defeat of Beachy Head caused panic in England. [The French commander] Tourville had temporary command of the English Channel; it seemed that the French could at the same time prevent William from returning from Ireland across the Irish Sea and land an invading army in England… To oppose the threatened invasion, 6,000 regular troops, together with the hastily organised militia, were prepared by the Earl of Marlborough for the country’s defence.

In the prevailing atmosphere of panic, no-one attributed the defeat to overwhelming odds. Nottingham accused Torrington of treachery, informing William on 13 July “In plain terms … Torrington deserted the Dutch so shamefully that the whole squadron had been lost if some of our ships had not rescued them.” Nottingham was anxious to shift blame but no one disputed his interpretation…

There was some good news for the Allies. The day after Beachy Head, 11 July, William decisively defeated Louis’ ally, King James, at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland. James fled to France but appeals to Louis for an invasion of England were not heeded. The Marquis de Seignelay, who had succeeded his father Colbert as naval minister, had not planned for an invasion and had thought no further than Beachy Head… Tourville anchored off Le Havre to refit and land his sick. The French had failed to exploit their success. To the fury of Louis and Seignelay, the sum of Tourville’s victory was the symbolic and futile burning of the English coastal town of Teignmouth in July; Tourville was relieved of command.

Fwiw, I find it surprising that Louis and his ministers had not considered an actual invasion of England (such as the English apparently feared so greatly at the time.)

Then, this happened:

The English squadrons rallied to the main fleet. By the end of August the Allies had 90 vessels cruising the Channel – temporary French control had come to an end. Torrington had been sent to the Tower of London to await a court martial at Chatham. The substance of the charge was that he had withdrawn and kept back, had not done his utmost to damage the enemy and to assist his own and the Dutch ships. Torrington blamed the defeat on the lack of naval preparations and intelligence… He also contended that the Dutch had engaged too early, before they had reached the head of the French line.

To the outrage and astonishment of William and his ministers – and the delight of the English seamen who, rightly or wrongly, regarded him as a political sacrifice to the Dutch – the court acquitted him. Torrington took up his seat in the House of Lords but William refused to see him and dismissed him from the service on 12 December (O.S).

This episode gives an interesting little window into how William was handling the strains of being both the Stadholder of Holland and the King of England…

(The banner image above is an early 19th-century engraving of the Battle of Beachy Head by De Gudin.)

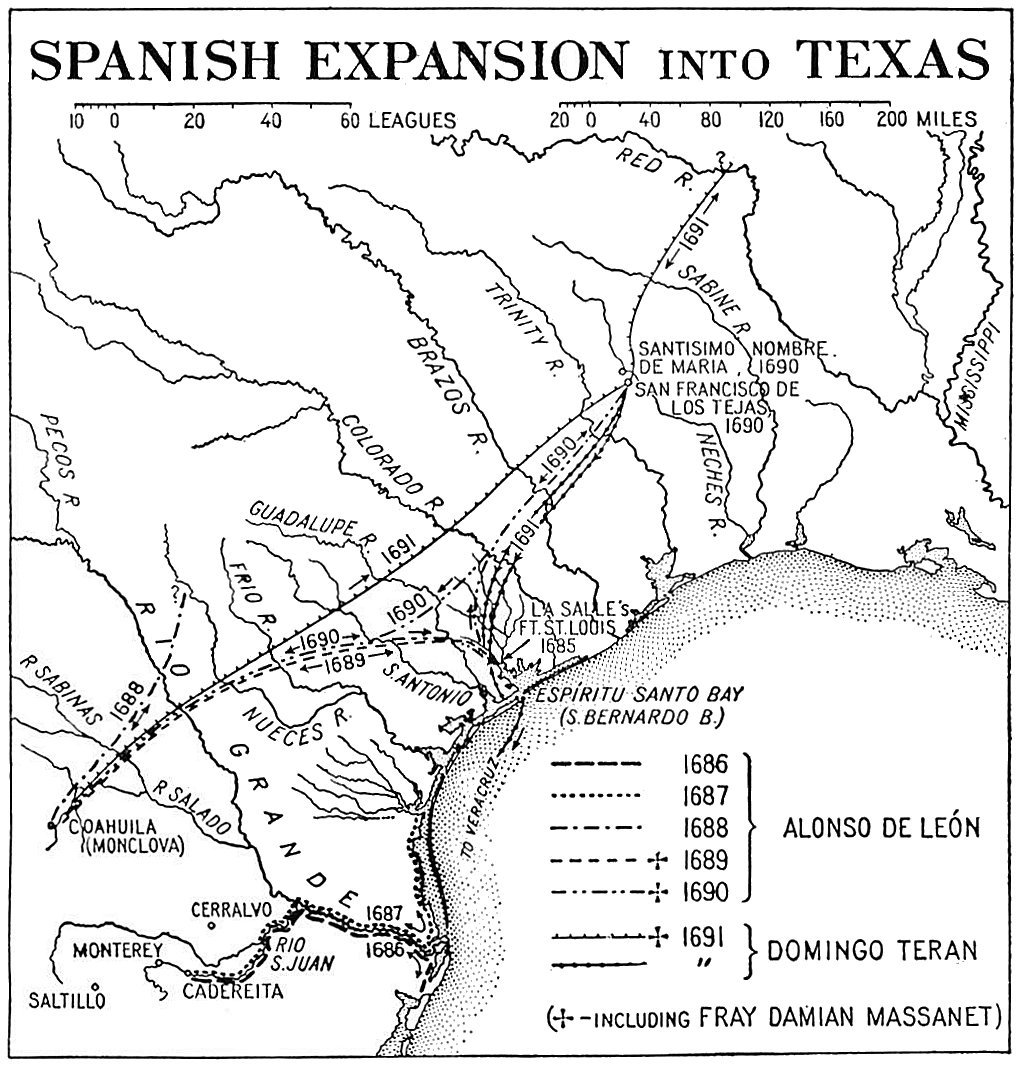

‘New Spain’ founds ‘Spanish Texas’

I am learning so much about the history of the Americas (and the West Indies) by doing this project… I guess I previously thought the Spanish had been in the area of today’s Texas for a long time by now. But no…

So you’ll recall that the French explorer Sieur de La Salle had “claimed” the whole of the Mississippi valley for France in 1682; and in 1684 he had sailed back with a large expedition through the (Spanish-controlled) Gulf of Mexico to establish a French fort at what he thought was the mouth of the Mississippi. On that occasion, WP tells us,

Due to a combination of inaccurate maps, La Salle’s previous miscalculation of the latitude of the mouth of the Mississippi River, and overcorrection for the currents, the expedition failed to find the Mississippi. Instead, they landed at Matagorda Bay in early 1685, 400 miles (640 km) west of the Mississippi.

Most of the Natives were decidedly unfriendly. What with one thing and another (including desertions) the expedition got whittled down to small numbers pretty quickly. La Salle and his remnants built a fort, later called Fort St. Louis, and started scouting the area. In April 1686, this happened:

[T]hey traveled east, hoping to locate the Mississippi and return to Canada. During their travels, the group encountered the Caddo, who gave the Frenchmen a map depicting their territory, that of their neighbors, and the location of the Mississippi River. The Caddo often made friendship pacts with neighboring peoples and extended their policy of peaceful negotiation to the French. While visiting the Caddo, the French met Jumano traders, who reported on the activities of the Spanish in New Mexico. These traders later informed Spanish officials of the Frenchmen they had seen.

Meantime, the La Salle group continued to be riven with internal dissension and incompetence. In January 1687, he decided their only hope for survival was to trek overland to the French-claimed “Illinois Country” and thence to Canada. Along the way, La Salle was killed by one of his expedition members. It’s not clear if any of them made it to “Illinois Country”. In 1868, the handful of people left at Fort St. Louis were vanquished by Karankawa-speaking Natives; and that was the end of the story…

Except that at some point there, the Spanish rulers in “New Spain” got the information– which apparently had surprised them– that there had been a French fort in Texas. So then, according to WP, this happened:

In 1690 Alonso de León escorted several Catholic missionaries to east Texas, where they established the first mission in Texas.

How long did this colonization attempt last? Not long. WP:

When native tribes resisted the Spanish invasion of their homeland, the missionaries returned to Mexico, abandoning Texas for the next two decades.

So I have to conclude that expansion into this portion of North America was not at all a high priority for New Spain. It’s worth remembering what a huge chunk of the world the New Spain capital in Mexico City was administering at that time: not just all of today’s Mexico and bit more up into today’s New Mexico and Arizona, but also the whole of Central America except today’s Panama; the whole of the Spanish-controlled Caribbean and Venezuela– and then the Philippines and a handful of other Pacific islands, as well. I guess they didn’t see anything of much value up in today’s Texas. And by the time they got to “Fort St. Louis” and saw how abandoned it was, they didn’t feel the need to stick around to combat the French there, either.

Mr. Barclay’s father-in-law founds a bank in London

The banking entity long known as Barclay’s bank was founded in November 1690, in London. English-WP tells us this about it:

Barclays traces its origins back to 17 November 1690, when John Freame, a Quaker, and Thomas Gould, started trading as goldsmith bankers in Lombard Street, London. The name “Barclays” became associated with the business in 1736, when Freame’s son-in-law James Barclay became a partner. In 1728, the bank moved to 54 Lombard Street, identified by the ‘Sign of the Black Spread Eagle’, which in subsequent years would become a core part of the bank’s visual identity.

The Barclay family were connected with slavery, both as proponents and opponents. David and Alexander Barclay were engaged in the slave trade in 1756. David Barclay of Youngsbury (1729–1809), on the other hand, was a noted abolitionist, and Verene Shepherd, the Jamaican historian of diaspora studies, singles out the case of how he chose to free his slaves in that colony.

I have to say the sourcing on that WP page is pretty poor. The item about David and Alexander Barclay being engaged in the slave trade is footnoted there to “Williams, Eric (1964), Slavery and Capitalism, p.116.” But Williams’s masterly book is titled Capitalism and Slavery, and the citation they need is not on p.116 but on p.101.

So here’s the original at p.101, in Williams’s section on the involvement of banks in the slavery business:

And here, fwiw, is an excerpt from his p.43, on the involvement of Quakers in the slave-trading “Royal African Company”: