Just two years earlier, in 1670 CE, France’s King Louis XIV had persuaded England’s King Charles II to conclude the “Secret Treaty of Dover”, that bound Charles to joining in an upcoming French attack against the Dutch, and in May 1672 the attack was launched. (Charles also committed to becoming a Catholic. It is unclear when that happened, but certainly before he died.)

In launching this attack, which was waged both by land and by sea, Louis and his able team of ministers were entering into that era’s “Great Game” of contests among the four West European powers that then commanded globe-circling commercial/military empires. The were directly attacking what at the time was the most vigorous and pugnacious participant in that Game. The Dutch empire was not nearly as extensive and wealthy as Spain’s; but Spain’s empire was in a longterm decline while the Dutch empire was looking very capable, especially in and around the Indian Ocean. And just recently, the Dutch had walloped England’s feisty navy in the seas between them, in the Second Anglo-Dutch War. In the 1672 attack, England’s navy would be supplemented by France’s formidable ground forces.

The war would have significant political repercussions in the Netherlands, and also in all the world’s oceans.

In the year’s other news, in August, the powerful Ottoman Grand Vizier Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed and his (nominal?) boss Sultan Mehmed IV led an army of 80,000 men into Polish Ukraine, taking the Polish-Lithuanian fortress at Kamieniec Podolski and besieging Lwów. This would be the start of a war between these two land-based central-European empires that would last four years.

And now, back to the main action…

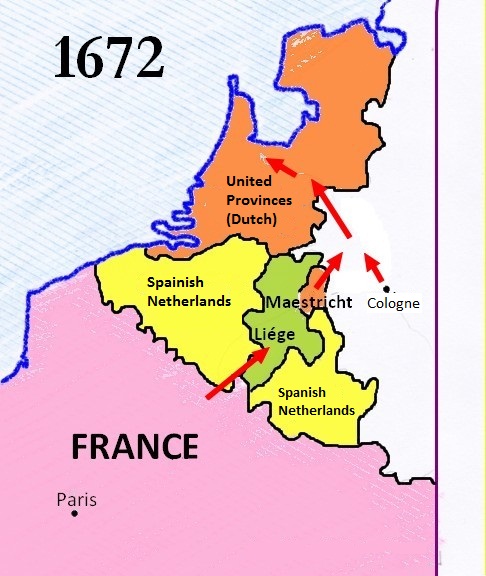

France’s diplomats and military leaders had been preparing for this attack for several years.They had strengthened their military positions in the frontier region and had pre-positioned many military supplies there. At the diplomatic level, in addition to winning the secret support of the English king, they had also concluded Agreements with the Bishopric of Münster and Electorate of Cologne that allowed French forces to bypass the Spanish Netherlands and had also bought some valuable support from Sweden, still a significant power in the area of today’s northern Germany.

English -WP tells us the French ground attack started on May 4, and over the month that followed pushed forward to seize control of significant portions of the Netherlands. By early summer the position was as shown at left. (Black was all French-controlled. Obviously, a different scale from the pink map above.)

For the Dutch, 1672 was known as the Rampjaar (disaster year.) The UPs’ most powerful member-province, Holland, had not had a Stadtholder since 1650. All power in Holland– and most of the power in the broader UP’s– been wielded by Holland’s chief civil servant, the Grand Pensionary, who since 1653 had been Johan De Witt, a pretty committed anti-monarchist, that is, an anti-Orangist. During his time in power, the UP’s had built up superb naval power and a big transoceanic empire that brought great profits to the Dutch merchant class. But clearly, he had under-invested in the UPs’ land forces and not been diplomatically smart enough to see the encirclement and attack that was coming.

The French advance of May and early June was a disaster for De Witt. He had long been under pressure from Dutch Orangists who had long wanted to have William Henry of Orange, the Prince of Orange, instated as Stadtholder of Holland and the other traditionally Orange-headed UP’s. Back in 1654, however, the States-General of Holland had promised England’s Oliver Cromwell, at the end of the First Anglo-Dutch War– which England won– that they would “exclude” the infant prince from this position. But William was now 22. He and his many domestic supporters argued vociferously that he should be allowed to take up his Stadtholdership. And in early 1672, De Witt had finally allowed him to be appointed Captain General of the Army.

But that did not prevent a large number of people in Holland from strongly blaming De Witt for the military disaster. On June 21, he was severely wounded by a knife-wielding assassin.

Throughout June, the French kept advancing. Under William Henry’s command, the Dutch fell back behind a remarkable series of defenses that his grandfather, Maurice of Nassau, had first planned back during the UPs’ 80-year war against Spain. This was the Dutch Water Line: a line of flooded land protected by fortresses that ran from the Zuiderzee (the present IJsselmeer) down to the river Waal. WP tells us this about it:

In 1629, Prince Frederick Henry [had] started the execution of the plan. Sluices were constructed in dikes, and forts and fortified towns were created at strategic points along the line with guns covering especially the dikes that traversed the water line. The water level in the flooded areas was carefully maintained at a level deep enough to make an advance on foot precarious and shallow enough to rule out effective use of boats (other than the flat bottomed gun barges used by the Dutch defenders). Under the water level additional obstacles… were hidden…

As the Dutch army fell back, William and other political leaders conducted sporadic negotiations with the French (and also, with the English; very smartly, the Dutch conducted these two sets of negotiations quite separately.) At this point, though, it seemed the French did not really know how they wanted this war to end. This page on WP tells us this about it:

The French were rather overwhelmed by their success. They had within a month captured three dozen fortresses. This strained their organisational and logistical capacities. All these strongholds had to be garrisoned and supplied. An intrusion into Holland proper seemed meaningless to them, unless Amsterdam could be besieged. This city would be a very problematic target. It had a population of 200,000 and could raise a large civil militia, reinforced by thousands of sailors… A deeper problem was that Amsterdam was the world’s main financial centre. The promissory notes with which many of the French military and the contractors had been paid, were covered by the gold and silver reserves of the Amsterdam banks. Their loss would mean the collapse of Europe’s financial system and the personal bankruptcy of large segments of the French elite.

Then, this previously unimaginable situation emerged:

In June, the Dutch seemed defeated. The Amsterdam stock market collapsed and their international credit evaporated… A single loyal ally remained: the Spanish Netherlands. They well understood that if the Dutch capitulated, they too would be lost. Though officially neutral, and forced to allow the French to transgress their territory with impunity, they openly reinforced the Dutch with thousands of troops.

Meantime, in England, Charles had been getting cold feet about the war project; and in addition, the naval part of the war, in which the English were playing the biggest part, had not been going well for them.

As soon as Johan De Witt saw how badly things were going for the UP’s on land, he had ordered Dutch admiral Michiel De Ruyter to launch a naval attack against the Anglo-French sea forces, sending his brother Cornelis de Witt to ensure these orders were carried out. The Dutch navy achieved this:

When the Allied fleet withdrew to Solebay near Southwold, Norfolk to resupply, on 7 June De Ruyter surprised it at the Battle of Solebay. The Duke of York led his squadrons against the main Dutch fleet, but his French colleague d’Estrées either misunderstood his intentions or deliberately ignored them, sailing in the opposite direction. The thirty French ships fought a separate encounter at long-range with fifteen ships from the Admiralty of Zeeland, under Adriaen Banckert. D’Estrées was later condemned by some of his own officers for failing to engage them more closely.

The Earl of Sandwich [who was Vice-Admiral of the English Navy] was killed when the Royal James was sunk by fireships, with other ships suffering heavy damage. Although ship losses were roughly equal, Solebay ensured the Dutch retained control of their coastal waters, secured their trade routes and ended hopes of an Anglo-French landing in Zeeland. Anger at the alleged lack of support from D’Estrées increased opposition to the war [in England], and Parliament was reluctant to approve funds for essential repairs. For the rest of the year, this restricted English naval operations to a failed attack on the Dutch East India Company Return Fleet.

The war continued to be very unpopular among England’s still very Protestant parliament, since he was seen as aiding the Catholic French against the solidly Protestant Dutch. (And this was true even long before anyone in Parliament knew anything about the “Secret Agreement” of 1670!) Seeing Parliament as disinclined to vote him the money he needed to fight the war, Charles now tried to re-position himself as someone able to make peace between the Dutch and the French.

On July 7, the Dutch Water Line was completely deployed. That gave the Dutch the chance to start enacting a much-needed reorganization of their land forces. On July 18, Charles sent a letter to William Henry reiterating peace terms he had already offered and claiming that Johan De Witt and his brother were the only obstacles to concluding a peace.

On August 15, this happened:

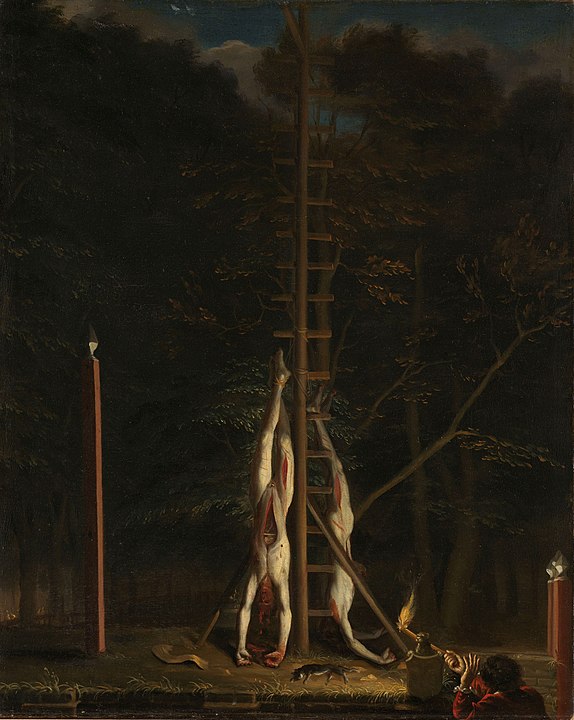

Charles’ letter blaming the De Witts was published in Holland [presumably by William or his allies]; motives are still debated but the effect was to inflame tensions and the two brothers were lynched by an Orangist civil militia on 20th.

The Johan De Witt page on Wikipedia gives more details about how this happened. Johan’s younger brother Cornelis was, it says, “particularly hated by the Orangists.” So Cornelis:

was arrested on trumped up charges of treason. He was tortured (as was usual under Roman-Dutch law, which required a confession before a conviction was possible) but refused to confess. Nevertheless, he was sentenced to exile. When his brother went over to the jail (which was only a few steps from his house) to help him get started on his journey, both were attacked by members of The Hague’s civic militia in a clearly orchestrated assassination. The brothers were shot and then left to the mob. Their naked, mutilated bodies were strung up on the nearby public gibbet, while the Orangist mob partook of their roasted livers in a cannibalistic frenzy. Throughout it all, a remarkable discipline was maintained by the mob, according to contemporary observers, making one doubt the spontaneity of the event.

I’m not sure how the reports of “remarkable discipline” can sit alongside “cannibalistic frenzy”… unless the cannibalism and other atrocities had all had a disciplined, almost ritualistic character to them? Anyway…

The Orangists hurried to install one of their own, Gaspar Fagel, as the new Grand Pensionary, and conducted a broad purge of De Witt supporters throughout the country.

Meantime, at the military level, over the months that followed William led three notable counter-attacks. This page on WP tells us two of these were,

over-ambitious and unsuccessful but [they] restored Dutch morale, while Coevorden was recaptured on 31 December. Although their position remained precarious, by the end of 1672 the Dutch had regained much of the territory lost in May and Louis found himself involved in a wider European war of attrition. Despite his French subsidies, Charles had run out of money and faced considerable domestic opposition to continuing the war. This increased when the Dutch Cape Colony dispatched an expeditionary force to the English-held island of Saint Helena, and took possession on behalf of the Dutch East India Company.

Oops. Not quite the quick and easy victory Charles had been hoping for. (To be continued in subsequent years.)

The banner image above is a painting of the Dutch recapture of Coevorden.