1673 CE was not a great year for England’s King Charles. The war against the Dutch United Provinces was (a) not going well and (b) leading to increasing political turmoil at home. By year’s end he was ready to make a (separate) peace with the Dutch– and in fact I’ll take today’s bulletin through the peace that he made in February 1674. Meantime, the gains that Charles’s original French allies had made on land, in continental Europe, had been having the (probably foreseeable) effect of pushing many European powers troubled by this demonstration of French power into some very non-ideological counter-alliances.

In other news, armed French explorers were active in North America and Bengal in 1673; a beloved French playwright died a paradoxical death; and a Polish polymath launched the world’s first rocket artillery. Scroll on down for all those developments.

England’s war against the Dutch UP’s fizzles, leads to discord at home

When we left the Anglo-French war effort against the Dutch UP’s at the end of last year, France had made some notable gains in the ground war, provoking an intense political crisis in Amsterdam that even involved the cannibalizing of the UP’s long-time “Grand Pensionary” and his brother. But the Dutch had stabilized the land-war situation by activating their brilliant “Water Line” defense, and had started to do pretty well in the sea war.

This portion of the WP page on the war tells us that in 1673 this happened:

After the French failed to breach the Holland Water Line, the Anglo-French fleet was tasked with defeating the Dutch navy, allowing them to blockade the Dutch coast and threaten the Republic with starvation, or land an invasion force. However, poor co-ordination meant they failed to exploit their numerical advantage, and [Dutch admiral] De Ruyter was able to prevent his fleet being overwhelmed. Although the Battle of Texel on 21 August was inconclusive, it was a strategic Dutch victory as the damage inflicted on the English fleet forced them to return home for repairs.

Never popular to begin with, English support for the war dissolved along with hopes for a quick victory. In late 1673, the French withdrew from the [Dutch] Republic, and focused on conquering the Spanish Netherlands, a frightening prospect for most English politicians. Combined with a Dutch pamphlet campaign claiming Charles had agreed to restore Catholicism, Parliament refused to fund the war, while the level of opposition made Charles fear for his own position…

It’s worth noting that prior to the inconclusive Battle of Texel, the Dutch navy had actually beaten the Anglo-French joint navy in two sea-battles fought in June near Schooneveld, also off the coast of Holland. Plus, around then too, the Dutch had also sent off a battle fleet of 23 ships to North America, which landed there on August 7 and recaptured the city and colony of New York from the English.

The war had never been popular in England. This page on WP gives us this background:

In 1673, sustained efforts by the Royal Navy to defeat the Dutch fleet and to land an army on the Dutch coast had failed. Repairs of the English warships proved to be very costly. English mercantile shipping suffered from frequent attacks by Dutch privateers. Meanwhile, France, the English ally in the war, was forced to a gradual withdraw of its troops from most of the territory of the United Provinces. France threatened to conquer the Spanish Netherlands, which would harm English strategic interests. The war, more or less a private project of Charles and never popular among the English people, now seemed to most to have become a hopeless undertaking.

The English had also been convinced by Dutch propaganda that the war was part of a plot to make their country Roman Catholic again. [Well, actually that was true!] The commander of the Royal Navy, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a devout Protestant, had begun to lead a vociferous movement aimed at breaking the French alliance. In late October, Charles asked Parliament for a sufficient war budget for 1674. Its members were extremely critical and denied that it was still necessary to eliminate the Dutch as commercial rivals because English trade had satisfyingly grown between 1667 and 1672. The proposed marriage of the King’s brother, the Duke of York, with the Catholic Mary of Modena was lamented. Parliament demanded securities for the defence of the Anglican Church against papism, the disbanding of the standing army (commanded by York) and the removal of pro-French ministers.

Well, actually, James, the Duke of York, was forced fairly early in 1673 to give up all his official positions in the English government. This was because in its campaign against Catholicism, parliament had in February passed legislation called the Test Act, which,

enforced upon all persons filling any office, civil or military, the obligation of taking the oaths of supremacy and allegiance and subscribing to a declaration against transubstantiation and also of receiving the [Anglican] sacrament within three months after admittance to office. The oath for the Test Act of 1673 was:

“I, N, do declare that I do believe that there is not any transubstantiation in the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, or in the elements of the bread and wine, at or after the consecration thereof by any person whatsoever.”

James had been a Catholic for around 15 years by then. He refused to perform any of the requirements of the Test Act and thus gave up his position as Lord High Admiral. He retained, however, his position as President of the Royal Africa Company. (But he had lost both the naming rights and the control over New York…)

The WP page on James also tells us that King Charles II had opposed James’s conversion, ordering that James’s daughters from his first marriage, Mary and Anne, be raised in the Church of England. His first wife had died in 1671. But then in 1673, this happened:

he allowed James to marry Mary of Modena, a fifteen-year-old [Catholic] Italian princess. James and Mary were married by proxy in a Roman Catholic ceremony on 20 September 1673. On 21 November, Mary arrived in England and Nathaniel Crew, Bishop of Oxford, performed a brief Anglican service that did little more than recognise the marriage by proxy… James was noted for his devotion. He once said, “If occasion were, I hope God would give me his grace to suffer death for the true Catholic religion as well as banishment.”

More about the discord the war caused in London in 1673, from here:

When the situation threatened to escalate, Charles, on the advice of the French envoy but against the opinion of the Privy Council, prorogued Parliament. Charles made a last effort to continue the war, even without a war budget. He was promised increased subsidies by King Louis XIV of France. He made plans to capture the regular treasure fleet sailing from the Dutch East Indies. He removed his enemies from office, among them Chancellor Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, the main opponent of York’s marriage. At the same time, Charles tried to lessen fears by reaffirming anti-Catholic measures such as the suspension of the Royal Declaration of Indulgence and by publicising many of his secret treaties with France.

(But not the one in which he himself had promised to become Catholic!)

But then, this:

To his dismay, Parliament became more adversarial, now strongly incited by Shaftesbury. Some called for William III of Orange, the [very Protestant] stadtholder of Holland and grandson of Charles I of England, to become king if Charles died by excluding the Duke of York. That came as no surprise to William, who had secret dealings with Shaftesbury and many other English politicians. William had agents working for him in England, such as his secretary, Van Rhede. Spain assisted him by threatening to declare war and meanwhile bribing parliamentarians. The States-General had supported the pro-Dutch peace party of Lord Arlington in a more formal manner by making a peace proposal in October and by regularly distributing manifests and declarations in England that explained the official Dutch position and policy. In 1672, England and France had agreed never to conclude a separate peace, but the States now revealed to Charles that they had recently received a peace offer from Louis.

When in late December, General François-Henri de Montmorency, duc de Luxembourg withdrew the bulk of the French occupation army from Maastricht to Namur, Charles lost faith completely and decided to disentangle himself from the entire affair… He informed the French ambassador, Colbert de Croissy, that to his regret, he had to terminate the English war effort.

Anglo-Dutch Treaty of February 1674

There was some amusing-sounding political theater as Charles and the Dutch moved to end the war:

On 4 January 1674, the States General of the Netherlands drafted a final peace proposal. On 7 January, a Dutch trumpeter arrived in Harwich carrying with him two letters for the Spanish consul. Though the herald was promptly arrested by the town mayor, the letters were sent to Lord Arlington, who hurriedly brought them in person to [Spanish consul] del Fresno. Arlington was, in turn, on 15 January, impeached… for high treason, as the very act showed him to have had secret dealings with the enemy. On 24 January, the consul handed the letters, containing the peace proposal, to Charles, who pretended to be greatly surprised. That posing was marred somewhat by the fact that he had especially recalled Parliament, prorogued by him in November, for that occasion the very same day. While addressing both Houses, Charles first emphatically denied the existence of any secret provisions of the Treaty of Dover and then produced the peace proposal, to the great satisfaction of the members, who, in turn, had to pretend surprise although Parliament had been informed by the Dutch beforehand of its full content. After some days of debate, the treaty was approved by Parliament.

This news was met with open joy by the populace. Charles sent his own trumpeter to Holland… The Treaty of Westminster was signed in 1674 by the King on 9 February Old Style (19 February New Style).

In 1672, Charles had sent a demand to the Dutch for an “indemnity” of ten million guilders. Now, in the 1674 treaty, he got them to agree to pay two million (basically, as a substitute for the cash payments he had previously been getting from the French king.) England won the symbolically important provision that the Dutch like all other maritime powers would have to dip their flags whenever they encountered an English vessel in the North Sea. And regarding the colonial holdings, they agreed to return to the status-quo ante of before the outbreak of war. The Dutch would give up “New Amsterdam”, which would once again become New York, and the English had to give up the Caribbean islands of Tobago, Saba, St Eustatius and Tortola, which they had seized from the Dutch in 1672.

Oh, and those two million guilders? William of Orange (who was Charles’s nephew, remember) suddenly pulled from his back pocket the creditor’s note that one of his grandfathers, England’s King Charles I, had given to his other grandfather, Maurice Prince of Orange, for the help Maurice gave to Charles I at the beginning of the civil war. So Charles II ended up getting very little cash at all.

France does some global exploring

France was still far behind England and the Dutch UP’s in its ability to create an armed global raiding/trading empire. But it was trying. In 1673, someone identified only as “Du Plessis” bought 13 “Arpents” of land near today’s Chandannagar, upstream a little on West Bengal’s Hooghly River. I’m guessing Du Plessis was acting for the French East India Company. Here’s what WP tells us:

Du Plessis… bought land of 13 Arpents at Boro Kishanganj, now located at North Chandannagar for Taka 401 in the year 1673–74.

The prosperity of Chandannagar as a French colony started soon after. At this time the Company establishment consisted of 1 Director, and 5 members who formed a council, 15 merchants and shopkeepers, 2 notaries, 2 padres, 2 doctors and 1 Sutradhar. The army consisted of 130-foot soldiers, 20 among them were native Indians. The Fort d’Orleans was constructed in the year 1696-97 and was better defended than its [?Portuguese] and British counterparts. After the initial success the French trade languished due to the lax policy of its Directors.

Not terribly promising, then. But in North America, French Jesuit Jacques Marquette and explorer Louis Jolliet were able to make a more lasting mark with the results of the explorations they made in 1673.

Marquette had been doing his “missionarying” (aka colonialist propagandizing or mind control) in La Pointe on Lake Superior in today’s Wisconsin, when he met members of “Illinois” tribes who told him about the important trading route of the Mississippi River. Then, this:

They invited him to teach their people, whose settlements were mostly farther south… [H]e informed his superiors about the rumored river and requested permission to explore it.

Leave was granted, and in 1673 Marquette joined the expedition of Louis Jolliet, a French-Canadian explorer. They departed from Saint Ignace on May 17, with two canoes and five voyageurs of French-Indian ancestry. They sailed to Green Bay and up the Fox River, nearly to its headwaters. From there, they were told to portage their canoes a distance of slightly less than two miles through marsh and oak plains to the Wisconsin River. Many years later, at that point, the town of Portage, Wisconsin was built, named for the ancient path between the two rivers. They ventured forth from the portage, and on June 17, they entered the Mississippi near present-day Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

The Joliet-Marquette expedition traveled to within 435 miles (700 km) of the Gulf of Mexico but turned back at the mouth of the Arkansas River. By this point, they had encountered several natives carrying European trinkets, and they feared an encounter with explorers or colonists from Spain. They followed the Mississippi back to the mouth of the Illinois River, which they learned from local natives provided a shorter route back to the Great Lakes. They reached Lake Michigan near the site of modern-day Chicago, by way of the Chicago Portage…

Marquette and his party returned to the Illinois territory in late 1674, becoming the first Europeans to winter in what would become the city of Chicago. As welcomed guests of the Illinois Confederation, the explorers were feasted en route and fed ceremonial foods…

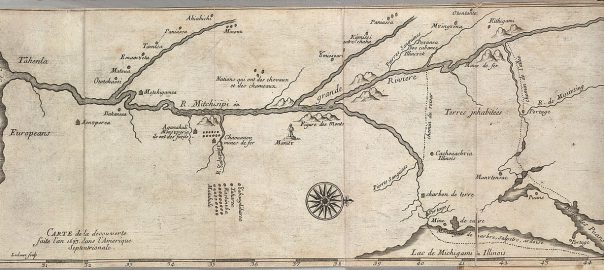

The banner image above is the map Marquette and Jolliet made of their expedition. North is to the right.

Death of a playwright

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, an actor and playwright better known by his stage name Molière was 51 years old and quite famous already in Paris, which under Louis XIV had seen an explosion of interest in the performing arts. In February 1673 he was acting in one of the early performances of his latest play Le Malade imaginaire when he collapsed on stage in a fit of coughing and haemorrhaging. He insisted on completing his performance. Then, this:

Afterwards he collapsed again with another, larger haemorrhage before being taken home, where he died a few hours later, without receiving the last rites because two priests refused to visit him while a third arrived too late…

Under French law at the time, actors were not allowed to be buried in the sacred ground of a cemetery. However, Molière’s widow, Armande, asked the King if her spouse could be granted a normal funeral at night. The King agreed and Molière’s body was buried in the part of the cemetery reserved for unbaptised infants.

If you don’t know what Le Malade imaginaire means, get it translated. Poor guy.

Kazimierz Siemienowicz invents, uses rocketry

Kazimierz Siemienowicz was a general of artillery, a gunsmith, military engineer, and pioneer of rockety who served in the armies of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and also of Frederick Henry, who had been the Prince of Orange before William. (A sort of rocketeering gun-for-hire like the much later Werner Von Braun…)

WP tells us this about him:

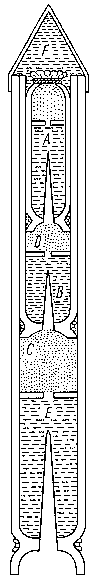

In 1650 Siemienowicz published a notable work, Artis Magnae Artilleriae pars prima (Great Art of Artillery, the First Part). Its name implies a second part, and it is rumored that he wrote its manuscript before his death. It is also rumored that he was killed by members of the metallurgy/gunsmith/pyrotechnics guilds, who were opposed to him publishing a book about their secrets, and that they hid or destroyed the manuscript of the second part…

For over two centuries this work was used in Europe as a basic artillery manual / handbook. Its pyrotechnic formulations were used for over a century. The book provided the standard designs for creating rockets, fireballs, and other pyrotechnic devices. It discussed for the first time the idea of applying a reactive technique to artillery (rocket artillery). It contains a large chapter on caliber, construction, production and properties of rockets for both military and civil purposes, including multistage rockets, batteries of rockets, and rockets with delta wing stabilisers (instead of the common guiding rods). It was the first book in the world to systematically present knowledge about the development of multistage rockets and rocket artillery.

Another page on Wikipedia told me that Siemienowicz first used rocket artillery in warfare in 1673, during the war the Poles were still fighting against the Ottomans that year.