1661 CE saw two developments of great world-historical impact. In Europe, the Regent to Portugal’s teenage king (Afonso VI) concluded an engagement of Afonso’s older sister Catherine of Braganza to the latest “hot catch” among Europe’s monarchy: England’s recently restored King Charles II. The dowry that Charles won with Catherine significantly expanded England’s imperial reach in several parts of the world. And off the coast of China, the well-trained amphibious forces of the pro-Ming general Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong) inflicted a defeat on the Dutch/VOC positions on Taiwan that was unexpected, massive, humiliating, and a big setback to Dutch ambitions in the East China region. It was also remarkably well documented by the defeated VOC commander.

1661 saw some continuing fallout from the big events of 1660, of course. (The posthumous execution of Oliver Cromwell, the crowning of King Charles II, etc…) And there were also three smaller developments in 1661. I’ll survey them quickly first, then get on to the year’s bigger news.

Smaller news of 1661

Death of the Chinese Emperor

China’s first Qing emperor, the Shunzhi Emperor, was still young, had only recently been able to rule free of his overbearing regent, Dorgon, and had only recently been able to gain control of the southern parts of his empire. In September 1660, his favorite consort died. English-WP tells us that this then happened:

Overwhelmed with grief, the emperor fell into dejection for months, until he contracted smallpox on 2 February 1661. On 4 February 1661, officials Wang Xi (王熙, 1628–1703; the emperor’s confidant) and Margi (a Manchu) were called to the emperor’s bedside to record his last will. On the same day, his seven-year-old third son Xuanye was chosen to be his successor, probably because he had already survived smallpox. The emperor died on 5 February 1661 in the Forbidden City at the age of twenty-two.

The Manchus feared smallpox more than any other disease because they had no immunity to it and almost always died when they contracted it. By 1622 at the latest, they had already established an agency to investigate smallpox cases and isolate sufferers to avoid contagion. During outbreaks, royal family members were routinely sent to “smallpox avoidance centers” (bidousuo 避痘所) to protect themselves from infection.

Xuanye would rule under the name the Kangxi Emperor. His rule would last 61 years.

Netherlands and Portugal conclude Treaty of The Hague

The Treaty of The Hague was signed on 6 August 1661 between representatives of the Dutch Empire and the Portuguese Empire. Based on the terms of the treaty, the Dutch Republic finally recognized Portuguese imperial sovereignty over all of former Dutch Brazil, in exchange for an indemnity equivalent to 63 tonnes of gold, to be paid over 16 years.

WP tells us that, “The treaty later led to a deal over Dutch Java and Portugal’s East Timor.” Basically, neither power would challenge the position of the other in its holdings in the East Indies.

Death of the Ottoman Grand Vizier

As we know, the wily survivor Köprülü Mehmed Pasha had been Grand Vizier in Istanbul since 1656, doing much to restore the efficiency of the Ottoman administrative regime. Now, aged 86, he dies. He had persuaded the pliant young Sultan to appoint his son Köprülüzade Fazıl Ahmed Pasha as Grand Vizier. (This guy looks just like his dad, so no need for a picture here.)

Catherine of Braganza and her generous dowry

Catherine was not yet two in 1640 when her father, the 8th Duke of Braganza, was chosen by the Portuguese Cortes to become King John IV of newly independent Portugal. WP tells us this about her marriage prospects:

With her father’s new position as one of Europe’s most important monarchs, Portugal then possessing a widespread colonial empire, Catherine became a prime choice for a wife for European royalty, and she was proposed as a bride for John of Austria, François de Vendôme, duc de Beaufort, Louis XIV and Charles II. The consideration for the final choice was due to her being seen as a useful conduit for contracting an alliance between Portugal and England, after the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659 in which Portugal was arguably abandoned by France…

Negotiations for the marriage began during the reign of King Charles I, were renewed immediately after the Restoration, and on 23 June 1661, in spite of Spanish opposition, the marriage contract was signed. England secured Tangier (in North Africa) and the Seven Islands of Bombay (in India), trading privileges in Brazil and the East Indies, religious and commercial freedom in Portugal, and two million Portuguese crowns (about £300,000). In return Portugal obtained British military and naval support (which would prove to be decisive) in her fight against Spain and liberty of worship for Catherine. She arrived at Portsmouth on the evening of 13–14 May 1662, but was not visited there by Charles until 20 May. The following day the couple were married at Portsmouth in two ceremonies – a Catholic one conducted in secret, followed by a public Anglican service.

Catherine had to put up with Charles’s continuing, constant womanizing. She got pregnant a few times but her pregnancies all ended in miscarriages. Also, this happened:

Catherine fainted when Charles’s official mistress, Barbara Palmer was presented to her. Charles insisted on making Palmer Catherine’s Lady of the Bedchamber. After this incident, Catherine withdrew from spending time with the king, declaring she would return to Portugal rather than openly accept the arrangement with Palmer. [Charles’s favorite Lord] Clarendon failed to convince her to change her mind. Charles then dismissed nearly all the members of Catherine’s Portuguese retinue, after which she stopped actively resisting, which pleased the king, however she participated very little in court life and activities.

So now, about those colonial “gifts”:

Tangier

Tangier had been held and garrisoned by the Portuguese since 1471 CE. English-WP tells us this: “As in Ceuta, they converted its chief mosque into the town’s cathedral church; it was further embellished by several restorations during the town’s occupation. In addition to the cathedral, the Portuguese raised European-style houses and Franciscan and Dominican chapels and monasteries.”

In 1661, this happened:

[An English] squadron under the admiral and ambassador Edward Montagu arrived in November. English Tangier, fully occupied in January 1662, was praised by Charles as “a jewell of immense value in the royal diadem” despite the departing Portuguese taking away everything they could, even—according to the official report—”the very fflowers, the Windowes and the Dores”. Tangier received a garrison and a charter which made it equal to other English towns [?], but the religious orders were expropriated, the Portuguese residents nearly entirely left, and the town’s Jews were driven out owing to fears concerning their loyalty. Meanwhile, the Tangier Regiment were almost constantly under attack by locals who considered themselves mujahideen fighting a holy war.

Spoiler alert: Tangier won’t stay English for very long.

Bombay

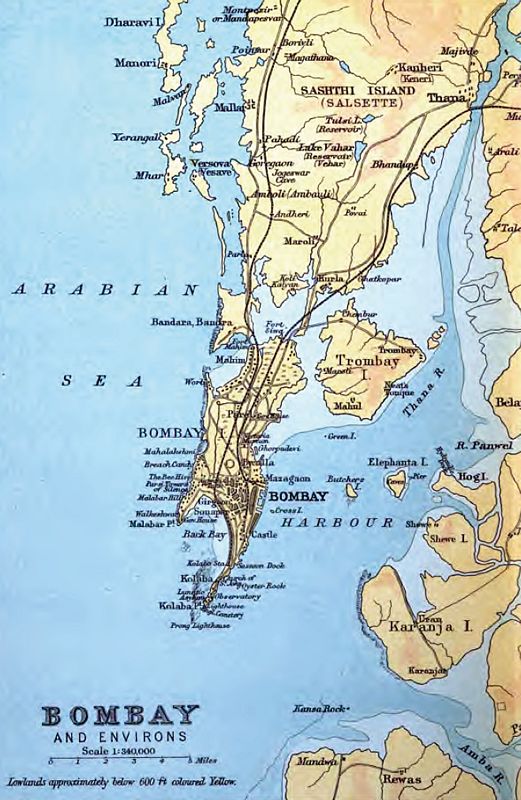

The Portuguese had been in Bombay– then a string of seven sandbank-islands off the west coast of India– since 1534. The Surat HQ of the English EIC had been trying to buy Bombay off the Portuguese for some years. Now, with the dowry arrangement signed and sealed, they didn’t have to!

However, the local Portuguese commanders did not leave easily. WP tells us this happened:

On 19 March 1662, Abraham Shipman was appointed the first [English] Governor and General of the city, and his fleet arrived in Bombay in September–October 1662. On being asked to hand over Bombay and Salsette to the English, the Portuguese Governor contended that Bombay Island alone had been ceded, and alleging irregularity in the patent, he refused to give up even Bombay Island. The Portuguese Viceroy declined to interfere and Shipman was prevented from landing in Bombay. He was forced to retire to the island of Anjediva in North Canara and died there in October 1664.

In November 1664, Shipman’s successor Humphrey Cooke agreed to accept Bombay Island without its dependencies, with the condition of granting special privileges to Portuguese citizens in Bombay, and no interference in the Roman Catholic religion. However, Salsette (including Bandra), Mazagaon, Parel, Worli, Sion, Dharavi, Wadala and Elephanta island still remained under Portuguese possession… From 1665 to 1666, Cooke managed to acquire Mahim, Sion, Dharavi, and Wadala for the English.

I will also here just speedily add some comments from the English historian Alfred Comyn Lyall (ACL), who wrote Vol. 8 of the informative series of histories of India, from Vol. 7 of which I’ve used excerpts covering earlier years.

On pp. 30-33 of his volume, ACL wrote this about what was happening in India in those years:

The beginning of [Aurangzeb’s long reign over the Mughal Empire], full of importance to Anglo-Indian history, synchronizes with the Restoration of Charles II, an event which changed the political connections of England and materially affected our commercial system. The [East India] Company wanted more extensive powers, and Charles II wanted to obliterate from their existing charter the name of Cromwell; so he gave them a new charter, authorizing them to make peace and war with any non-Christian people, although in fact their only troublesome enemies belonged to Christendom.

Portugal now sought the English alliance in the hope of recovering some of her Eastern possessions that she had lost while under the Spanish yoke, or at least of defending against the Dutch what she had been able to retain. These negotiations brought us the valuable acquisition of the island of Bombay, which was ceded to England in 1661 as the pledge of an arrangement for a kind of defensive war against the Dutch in Asia. But since the Portuguese were as jealous of the English as they were afraid of the Dutch, some years passed before the English found themselves in quiet possession of the island; nor was it until 1669 that Bombay and St. Helena were granted in full property to the London Company.

In 1661 Charles II had granted to this Company by charter the entire English traffic in the East Indies, with license to coin money, administer justice, and punish interlopers; and he confirmed their authority to make war and peace with non-Christian states in those parts. He also adopted Cromwell’s famous Navigation Law, which was devised to give British sailors and shipping a monopoly of the transport of goods interchanged with England, and was aimed chiefly at the Dutch, who were then the principal carriers of the sea-borne trade of Europe.

In this manner the commercial resources of England were formed, organized, and directed toward maintaining an equal contest against inveterate foes; nor can there be any doubt that trade monopolies were in those days essential to the existence of British commercial settlements in Asia. England then had no diplomatic representatives in non-Christian countries; the home governments paid no attention to the grievances of any single merchant or ship-master; and the Amboyna massacre is only one example of the reckless methods in use among commercial rivals in distant countries. Without large capital, an armament, and authority to use it, without some kind of rough jurisdiction over their countrymen in distant settlements, no mercantile association could preserve sufficient influence at home or security for their foreign stations and their ships at sea.

All these measures for strengthening the East India trade angered the Dutch…

Koxinga humiliates, routs the Dutch

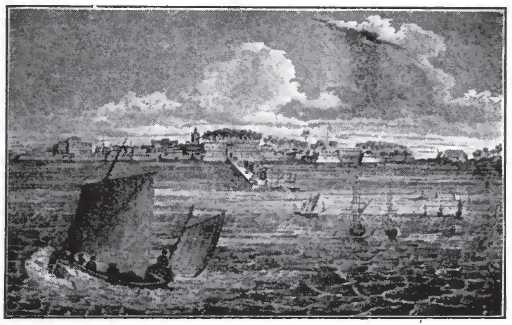

In 1659, we had seen how the Qing had been consolidating their rule over mainland China. One holdout was still the former pirate-chief Zheng Chenggong, also known as Koxinga, who had earlier allied himself with the Ming (in their last years), while his father Zheng Zhilong had allied himself with the up-and-coming Qings. At that point, Koxinga felt himself boxed into, roughly, the southeast corner of the Chinese mainland and, looking around for a way to regroup and consolidate his forces, he thought of Taiwan. Given that had significant amphibious capabilities and forces, escaping oveer there and building a refuge for himself over there must have seemed like a natural move. The main thing that was in his way was the big fort the Dutch had built at the southwest of the island, Fort Zeelandia, and its smaller dependent fort, Fort Provintia. forts.

Zeelandia at the time was commanded by VOC commander Frederick Coyett. He had 1,900 fighters at his command, and 14 warships. On March 23, 1661, this happened:

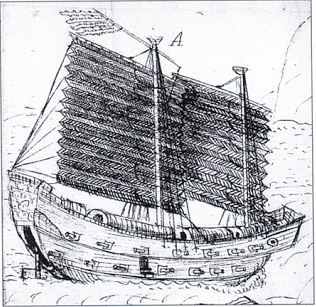

Koxinga’s fleet set sail from Kinmen (Quemoy) with hundreds of junks of various sizes, with roughly 25,000 soldiers and sailors aboard. They arrived at Penghu [a small archipelago in the Taiwan Strait] the next day. On 30 March, a small garrison was left at Penghu while the main body of the fleet left and arrived at Tayoan on April 2. On Baxemboy Island in the Bay of Taiwan, unrelated to the siege, 2,000 Chinese attacked 240 Dutch musketeers, routing them. After passing through a shallow waterway unknown to the Dutch, [Koxinga’s attack force] landed at the bay of Lakjemuyse. Four Dutch ships attacked the Chinese junks and destroyed several but one of their own squadron was burnt by fire boats. The rest [of the Dutch ships] escaped from the harbor, two to return, while the third sailed for Batavia, not reaching her destination until after some fifty days owing to the south monsoon… The remainder of Koxinga’s men were safely landed and built earthworks overlooking the plain.

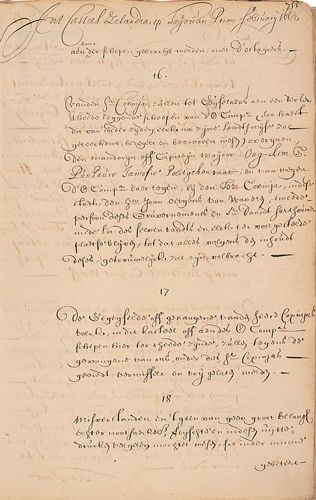

Because of the humiliation that Coyett suffered over the days ahead, he was later charged with high treason by his VOC masters and imprisoned for three years. But he justified the actions he had taken at Zeelandia by writing a detailed description of the battles he (unsuccessfully) fought against Koxinga’s surprisingly capable and well-organized forces. Much or most of his description was later translated into English and appeared in William Campbell’s 1903 book Formosa Under the Dutch, the full text of which is now available online, here.

Coyett was clearly impressed by the organization and tactics used by Koxinga’s forces, who had tight phalanxes of capable archers, fighters with sword-sticks, flexible and effective body armor– and also, cannons, ammunition, rifles, and muskets.

As Campbell’s translation tells us:

The latter courageously marched in rows of twelve men towards the enemy, and when they came near enough, they charged by firing three volleys uniformly. The enemy, not less brave, discharged so great a storm of arrows that they seemed to darken the sky. From both sides some few fell hors de combat, but still the Chinese were not going to run away, as was imagined. The Dutch troops now noticed the separated Chinese squadron which came to surprise them from the rear; and seeing that those in front stubbornly held their ground, it now became a case of sero sapiunt Phryges. They now discovered that they had been too confident of the weakness of the enemy, and had not anticipated such resistance. If they were courageous before the battle (seeking to emulate the actions of Gideon), fear now took the place of their courage, and many of them threw down their rifles without even discharging them at the enemy. Indeed, they took to their heels, with shameful haste, leaving their brave comrades and valiant Captain in the lurch…

But it was observed that the greatest part of the hostile army—which, according to one of the prisoners, amounted to twenty thousand men, Koxinga himself being present—had already landed on the Sakam shore. To all appearance they would probably resist, pursue, and defeat us, seeing that they had a large force of cavalry, and were armed with rifles, soapknives [sword-sticks], bows and arrows, and such like weapons, besides being harnessed and provided with storm-helmets.

Fort Provintia was the first to surrender. Then, per WP, this:

On April 7, Koxinga’s army surrounded Fort Zeelandia, sending the captured Dutch priest Antonius Hambroek as emissary demanding the garrison’s surrender. However, Hambroek urged the garrison to resist instead of surrender and was executed after returning to Koxinga’s camp. Koxinga ordered his artillery to advance and used 28 cannons to bombard the fort. Koxinga’s fleet then began a massive bombardment; troops on the ground attempted to storm the fort, but were repulsed with considerable losses. Koxinga then changed his tactics and laid siege to the fort.

The siege lasted many months. (Rad all about it on Wikipedia.) Along the way, the VOC headquarters at Batavia had sent along a relief force of 10 ships and 700 soldiers, but the wily tactics of Koxinga’s sailors managed to defeat them. Finally, on January 12, 1662, this happened:

Koxinga’s fleet initiated another bombardment, while the ground force prepared to assault the fort. With supplies dwindling and no sign of reinforcement, Coyett finally ordered the hoisting of the white flag and negotiated terms of surrender, a process that was finalized on February 1. On the 9th of February, the remaining Dutch East India Company personnel left Taiwan; all were allowed to take with them their personal belongings, as well as provisions sufficient for them to reach the nearest Dutch settlement.

WP tells us that:

After the loss of the post at Tayoan, the Dutch East India Company mounted several attempts at recapture—even forming an alliance with the Qing Empire to defeat Koxinga’s fleet. The alliance captured Keelung in northern Taiwan, but was forced to abandon it because of logistical difficulties and the inferiority of the Qing fleet when pitted against Koxinga’s veteran sailors.

As for what Koxinga did with Taiwan after he had ejected the Dutch, this page on him on WP tells us he:

devoted himself to transforming Taiwan into a military base for loyalists who wanted to restore the Ming dynasty.

Koxinga formulated a plan to give oxen and farming tools and teach farming techniques to the Taiwan Aboriginals, giving them Ming gowns and caps, and gifting tobacco to Aboriginals who were gathering in crowds to meet and welcome him as he visited their villages after he defeated the Dutch.

He also established his own kingdom, the Kingdom of Tungning, in Taiwan, and launchd a few raids against the Spanish Philippines.

But very soon after he had ejected the Dutch, this happened:

Koxinga died of malaria in June 1662, only a few months after defeating the Dutch in Taiwan, at the age of 37. There were speculations that he died in a sudden fit of madness when his officers refused to carry out his orders to execute his son Zheng Jing. Zheng Jing had had an affair with his wet nurse and conceived a child with her. Zheng Jing succeeded his father as the King of Tungning.

As he descended into death, Koxinga relented and agreed to let his son Zheng Jing succeed him. Koxinga died as he passed into delirium and madness and expressed his regrets to his family and father.

The banner image above is a detail from yet another engraving of Fort Zealandia.