Alert readers will recall that the anti-monarchist movement in England had fallen into chaos when Cromwell died in 1658 CE. So below, I will tell you more about what this led to in 1660– Restoration of the monarchy, punishment of the regicides, establishment of the Royal African Company, etc.

But first, let’s go to Martinique, where the French had been running slave-worked plantations since they captured the island in 1635, and to Boston, Massachusetts, where the Puritan authorities exercised some extreme religious intolerance.

Genocide & ethnic cleansing in Martinique

I think the English-WP page on this event is far too forgiving of the actions of the French, but here’s what it says:

In 1635 the Carib were overwhelmed by French forces… who imposed French colonial rule on the indigenous Carib peoples. Cardinal Richelieu of France gave the island to the Saint Christophe Company, in which he was a shareholder. [!] Later the company was reorganized as the Company of the American Islands. The French colonists imposed French Law on the conquered inhabitants, and Jesuit missionaries arrived to convert them to the Roman Catholic Church.

Because the Carib people resisted working as laborers to build and maintain the sugar and cocoa plantations which the French began to develop in the Caribbean, in 1636 King Louis XIII proclaimed La Traite des Noirs. This authorized the capture or purchase of slaves from Africa, who were then transported as labor to Martinique and other parts of the French West Indies

In 1650, the Company liquidated and sold Martinique to Jacques Dyel du Parquet, who became governor until his death in 1658. His widow then took control of the island for France. As more French colonists arrived, they were attracted to the fertile area known as Cabesterre (leeward side). The French had pushed the remaining Carib people to this northeastern coast and the Caravalle Peninsula, but the colonists wanted the additional land. The Jesuits and Dominicans agreed that whichever order arrived there first, would get all future parishes in that part of the island. The Jesuits came by sea and the Dominicans by land, with the Dominicans’ ultimately prevailing.

When the Carib revolted against French rule in 1660, the Governor Charles Houel sieur de Petit Pré retaliated with war against them. Many were killed; those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island.

On Martinique, the French colonists signed a peace treaty with the few remaining Carib. Some Carib had fled to Dominica or St. Vincent, where the French agreed to leave them at peace. However, following the British conquest of these islands, the Caribs would eventually be expelled to Central America after losing the Second Carib War.

Massachusetts executes a Quaker

Mary Dyer was born in 1611 to a Puritan family. In the early 1630s, she and her spouse William went as colonists to the young Massachusetts Bay Colony. But because of religious differences they were banished from there and moved to Rhode Island. In 1651, she returned to England, where she became a follower of George Fox’s new “Quaker” sect.

English-WP tells us this happened:

Because Quakers were considered among the most heinous of heretics by the Puritans, Massachusetts enacted several laws against them. When Dyer returned to Boston from England, she was immediately imprisoned and then banished. Defying her order of banishment, she was again banished, this time upon pain of death. Deciding that she would die as a martyr if the anti-Quaker laws were not repealed, Dyer once again returned to Boston…

There, she swiftly became one of three Quaker preachers sentenced to death in October 1659. The authorities hanged each of the other two first, by hanging:

and then it was Dyer’s turn after she witnessed the execution of her two friends. Dyer’s arms and legs were bound and her face was covered with a handkerchief… She stood calmly on the ladder, prepared for her death, but as she waited, an order of a reprieve was announced. A petition from her son, William, had given the authorities an excuse to avoid her execution. It had been a pre-arranged scheme, in an attempt to unnerve and dissuade Dyer from her mission. This was made clear from the wording of the reprieve, though Dyer’s only expectation was to die as a martyr…

The courage of the martyrs led to a popular sentiment against the authorities who now felt it necessary to draft a vindication of their actions…

Mary Dyer then went to Rhode Island and Long Island to consider what to do. She finally felt led (as Quakers say) “to return to Boston to force the authorities to either change their laws or to hang a woman.” She returned to Boston in May 1660. Governor Endicott asked her if she was still a Quaker, and she replied that she was. Then this:

On 1 June 1660, at nine in the morning, Mary Dyer once again departed the jail and was escorted to the gallows. Once she was on the ladder under the elm tree she was given the opportunity to save her life. Her response was, “Nay, I cannot; for in obedience to the will of the Lord God I came, and in his will I abide faithful to the death.” The military commander, Captain John Webb, recited the charges against her and said she “was guilty of her own blood.”

… Another short exchange followed, and then, in the words of her biographer, Horatio Rogers, “she was swung off, and the crown of martyrdom descended upon her head.”

We also learn that in 1661 this happened:

the English Quaker activist Edward Burrough was able to get an appointment with the king. In a document dated 9 September 1661 and addressed to Endicott and all other governors in New England, the king directed that executions and imprisonments of Quakers cease, and that any offending Quaker be sent to England for trial under the existing English law.

While the royal response put an end to executions, the Puritans continued to find ways to harangue the Quakers who came to Massachusetts… [I]n 1665, a royal commission directed that all legal actions taken against Quakers would cease. Nevertheless, whippings and imprisonments continued into the 1670s, after which popular sentiment, coupled with the royal directives, finally put an end to the Quaker persecution.

George Monck & others orchestrate Restoration of monarchy in England

Here’s how Charles Stuart, the aspirant to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland who had been living in Netherlands, managed to get what he wanted:

After the death of Cromwell in 1658, Charles’s initial chances of regaining the Crown seemed slim; Cromwell was succeeded as Lord Protector by his son, Richard. However, the new Lord Protector had little experience of either military or civil administration. In 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled and Richard resigned. During the civil and military unrest that followed, George Monck, the Governor of Scotland, was concerned that the nation would descend into anarchy. Monck and his army marched into the City of London, and forced the Rump Parliament to re-admit members of the Long Parliament who had been excluded in December 1648, during Pride’s Purge. The Long Parliament dissolved itself and there was a general election for the first time in almost 20 years. The outgoing Parliament defined the electoral qualifications intending to bring about the return of a Presbyterian majority.

The… elections resulted in a House of Commons that was fairly evenly divided on political grounds between Royalists and Parliamentarians and on religious grounds between Anglicans and Presbyterians. The new so-called Convention Parliament assembled on 25 April 1660, and soon afterwards welcomed the Declaration of Breda, in which Charles promised lenience and tolerance. There would be liberty of conscience and Anglican church policy would not be harsh. He would not exile past enemies nor confiscate their wealth. There would be pardons for nearly all his opponents except the regicides. Above all, Charles promised to rule in cooperation with Parliament. The English Parliament resolved to proclaim Charles king and invite him to return, a message that reached Charles at Breda on 8 May 1660. In Ireland, a convention had been called earlier in the year, and had already declared for Charles. On 14 May, he was proclaimed king in Dublin.

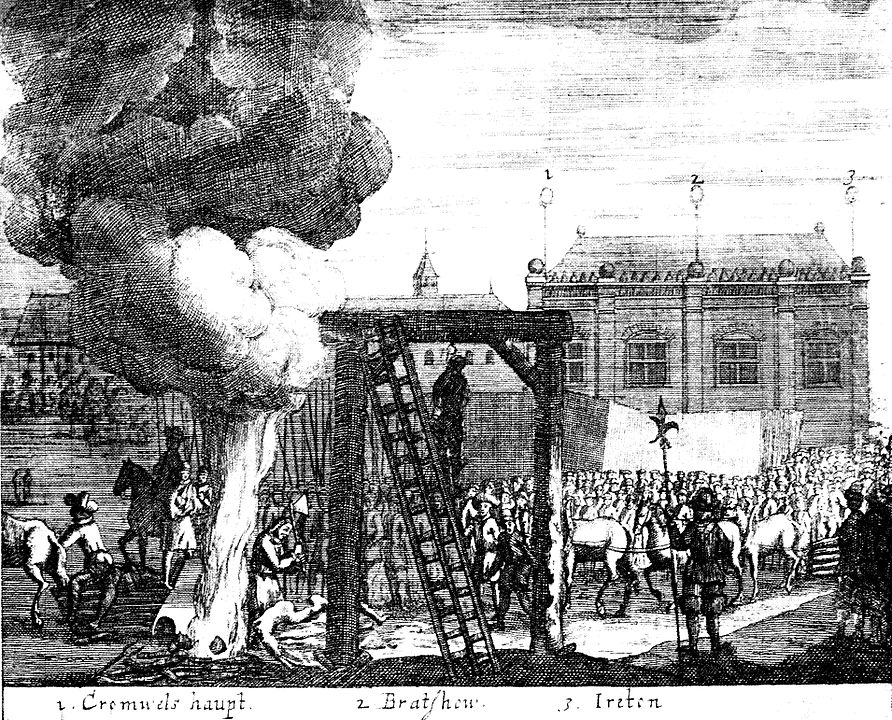

He set out for England from Scheveningen, arrived in Dover on 25 May 1660 and reached London on 29 May, his 30th birthday. Although Charles and Parliament granted amnesty to nearly all of Cromwell’s supporters in the Act of Indemnity and Oblivion, 50 people were specifically excluded. In the end nine of the regicides [judged responsible for the execution of Charles I] were executed: they were hanged, drawn and quartered; others were given life imprisonment or simply excluded from office for life. The bodies of Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw were subjected to the indignity of posthumous decapitations…

In the latter half of 1660, Charles’s joy at the Restoration was tempered by the deaths of his youngest brother, Henry, and sister, Mary, of smallpox. At around the same time, Anne Hyde, the daughter of the Lord Chancellor, Edward Hyde, revealed that she was pregnant by Charles’s brother, James, whom she had secretly married. Edward Hyde, who had not known of either the marriage or the pregnancy, was created Earl of Clarendon and his position as Charles’s favourite minister was strengthened.

The Convention Parliament was dissolved in December 1660, and, shortly after the coronation, the second English Parliament of the reign assembled. Dubbed the Cavalier Parliament, it was overwhelmingly Royalist and Anglican. It sought to discourage non-conformity to the Church of England and passed several acts to secure Anglican dominance… The Acts became known as the Clarendon Code, after Lord Clarendon, even though he was not directly responsible for them and even spoke against [one of them.]

By the way, the banner image above is a painting of Charles leaving Scheveningen on his triumphal return to London.

King Charles II hastens to found ‘Royal African Company’

The Royal African Company (RAC), originally known as the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, was an English trading company set up in 1660 by the royal Stuart family and City of London merchants to trade along the west coast of Africa. King Charles granted the company a charter that gave it a monopoly on all English trading with West Africa. His unemployed brother James, Duke of York, headed the company. (James would later take the throne as King James II.)

English-WP tells us that during the 90 years of the RAC’s existence it would ship more enslaved Africans to the Americas than any other company in the history of the Atlantic slave trade.

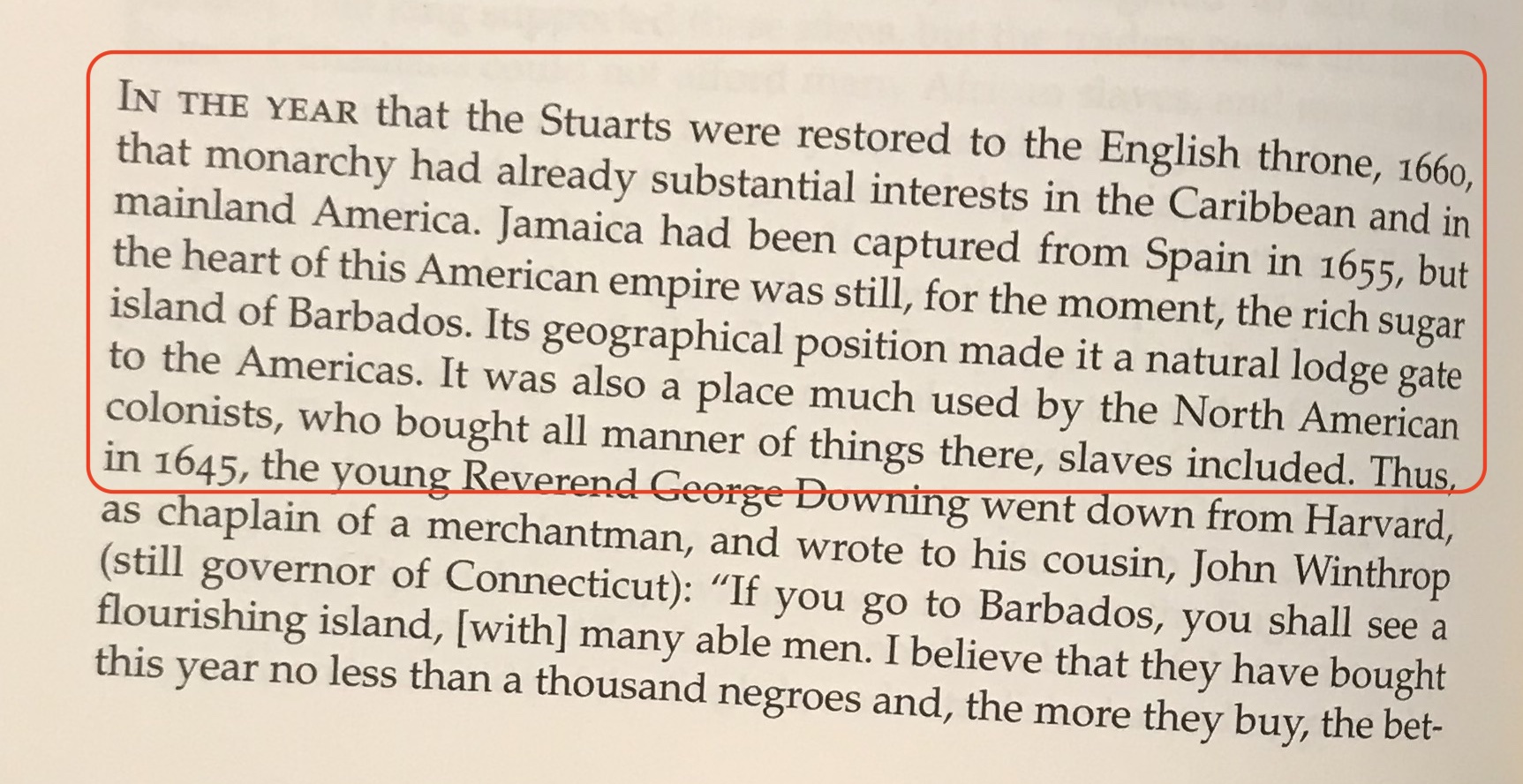

The historian Hugh Thomas tells us this in his masterly study The Slave Trade (p.196):

Thomas notes (p.198) that each of the investors in the new company had to invest £250 in it. He tells us that on the list of investors were, “four members of the royal family, two dukes, a marquis, five earls, four barons, and seven knights. Though the company was managed by a committee of six (headed by Lord Craven), it seemed more an ‘aristocratic treasure hunt than an organized business’.”

The RAC would get a new charter in 1663, and we’ll come back to it then.