Without a doubt, the main development in 1644 CE was the ousting of the Ming Dynasty from Beijing and, after further turmoil there, the installation of the robust and longlasting Qing Dynasty. Other notable events in the continuing story of the rise of “the West” were the uprising that the capable but ageing Powhatan chief Opechancanough launched against the Anglo colonists in “Virginia”, and the exploration travels that Abel Tasman continued to conduct around “Australia”, on behalf of the Dutch VOC.

Two other remaining stories were:

- the continuation of the English Civil War, which saw the front-line between Royalists and Parliamentarians shifting back and forth and the creation by the Parliamentary side of a committee to coordinate anti-Royalist actions in England, Scotland, and Ireland; and

- some lingering after-effects of Portugal’s 1640 secession from Spain, including an inconclusive battle between the two armies at Montijo, Spain, and the murder in a church in Portuguese-held Macau (in China) of a Spanish officer who had sought refuge there from an angry, presumably Portuguese, mob. (The banner image above is a detail from a Portuguese tilework image of the Battle of Montijo.)

Let’s travel speedily through the Abel Tasman and Opechancanough stories and end up in China.

Abel Tasman maps northern Australia

Abel Tasman was a Dutch seafarer sailing for the very powerful Dutch East India Company (VOC) out of their Batavia headquarters. He had made one earlier exploration voyage in 1642-43, in the course of which he had circumnavigated Australia– giving it a wide berth and making some form of contact in late 1642 with Aotearoa/ New Zealand along the way. (On that occasion, he thought he might have reached land that connected with the southern tip of South America, but Hendrik Brouwer’s expedition to Valdivia in 1643 proved that not to be the case. He was also attacked by Māori in a double-hulled waka canoe who killed four of his men.)

That first trip had proved that Australia was not, as had earlier been surmised, connected to the presumed great landmass of the South Pole. So in January 1644 the VOC sent him back to find out more about the big land of Australia. On this occasion, he sailed west along the north coast of Australia, which he had named “New Holland.” He had taken with him the artist Issack Gilsemans and between them they did some documentation of the land and its people and got back to Batavia in August 1644.

English-WP tells us, however, that,

From the point of view of the Dutch East India Company, Tasman’s explorations were a disappointment: he had neither found a promising area for trade nor a useful new shipping route… [T]he company was upset to a degree that Tasman did not fully explore the lands he found, and decided that a more “persistent explorer” should be chosen for any future expeditions. For over a century, until the era of James Cook, Tasmania and New Zealand were not visited by Europeans – mainland Australia was visited, but usually only by accident.

Maybe the reception he had gotten from the Māori two years earlier had made him wary about simply landing on and expropriating somebody else’s land?

Opchancanough’s last stand

Opchancanough had been the paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy in the southeast of today’s Virginia for a long time. And for all that time his people had been under relentless pressure from the English land-stealers and exploiters of the “Jamestown” colony, who introduced into the area they occupied many strange new customs including private property (including in land and in enslaved persons), the commercial exploitation of land to produce an export crop (tobacco), the supremacy of someone called a “Christian God” (of the Anglican variety), “White” supremacy and the righteousness of expelling indigenous peoples from land they had lived on and gently used for generations, and so on…

In 1622, he had led the anti-colonial uprising that killed hundreds of colonists and forced them to regroup their settlements– and he had seen and survived the terrible mass poisoning incident that the settlers planned in revenge– at a “peace” ceremony, no less.

In April 1644, he led another attempt to expel the colonial usurpers. This time around, the uprising lasted more than two years. This page on WP tells us that around 400 colonists were killed this time around. Then, in 1646, this:

In August, Governor William Berkeley stormed the village where Opechancanough resided and captured him. All captured males in the village older than 11 were deported to Tangier Island. Opechancanough was taken to Jamestown and imprisoned. Very old and infirm, unable to even move without assistance, Opechancanough died in captivity in October of 1646, murdered by his English guard. By this time Necotowance had succeeded him as the last Mamanatowick of the Powhatan Confederacy.

In October 1646 the General Assembly of Virginia signed a peace treaty with Necotowance, King of the Indians, which brought the Third Anglo-Powhatan War to an end. In the treaty, the tribes of the Confederacy became tributaries to the King of England, paying a yearly tribute to the Virginia governor. At the same time, a racial frontier was delineated between Indian and colonial settlements, with members of each group forbidden to cross to the other side except by a special pass obtained at one of the border forts.

As we know, the negotiated and agreed “Red Line” there was completely insufficient to contain the land-greed of the colonists.

Dynastic change in China and a look back at the Ming

Over years past, I have reported on several aspects of what was going on in China: the continuing decadence (and frequent cruelty) of the Ming emperors; the notable resilience and general capability of the bureaucratic class; the serious fraying of the edges of imperial authority especially along China’s lengthy eastern coast; the raiding by pirates and traders and numerous actors who were both, and the need for the Chinese authorities to come to terms with them on some basis…

Oh, and let’s not forget the massive crumbling of imperial authority throughout the massive landmass of traditionally Chinese East Asia, which reaches a series of significant watersheds this year:

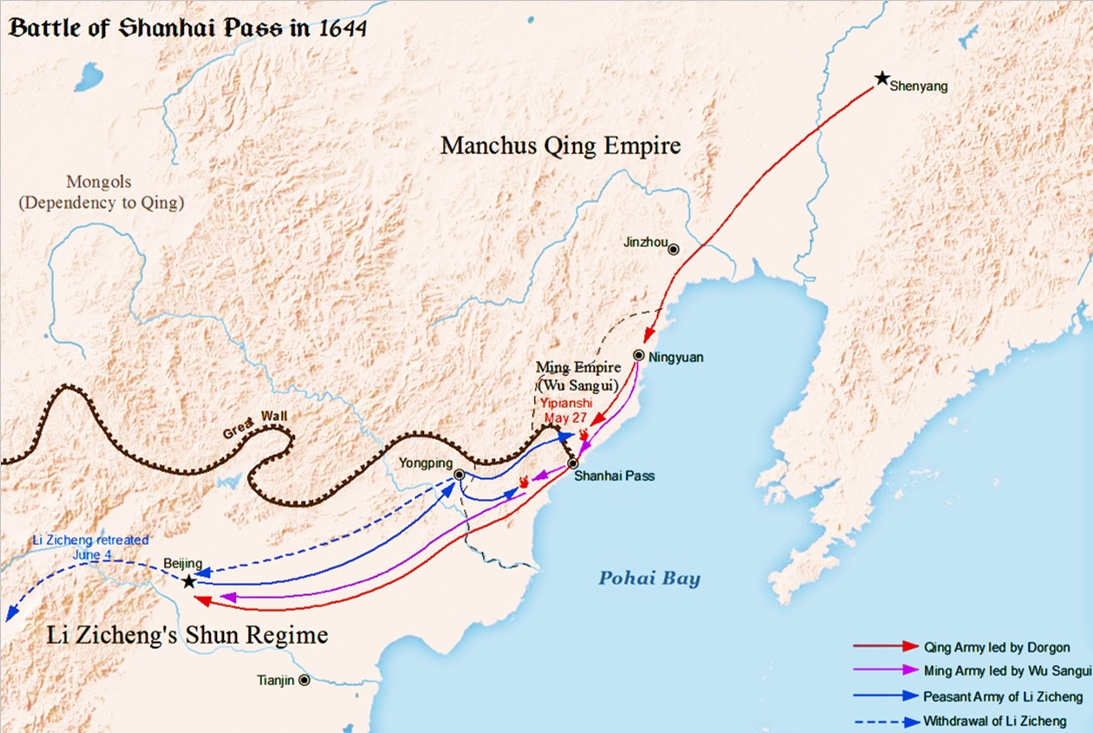

- On April 25, the peasant rebellion force led by Li Zicheng sacked Beijing, prompting the Chongzhen Emperor to kill himself, either by hanging or strangling.

- On May 25, the leading Ming general Wu Sangui formed an alliance with the leaders of the Qing (Manchu) forces, who had assembled huge power in the north over preceding decades. Wu opened the gates of the Great Wall at Shanhai Pass, letting the Manchus come through in great numbers to Beijing.

- On May 27, Wu and his Qing allies fought a battle against Li Zicheng’s forces at Shanhai Pass, beating them decisively.

- On June 3, Li declared himself Emperor of China. But to little avail, because–

- On June 6, the Qing army captured Beijing. (I guess they then had some work to do restoring order there and organizing their new administration there?)

- On November 8, the Shunzhi Emperor, now all of five years old, was enthroned as the first emperor of China’s new Qing Dynasty. For the first years of his reign there was a regency council. The dynasty would rule China until 1912.

The remnants of the Ming scattered to the south where they continued to have a presence on the mainland until 1664, at which point they decamped to Taiwan.

The Ming Dynasty had ruled China since 1368 CE, lasting just shy of 300 years. The English-WP page on the dynasty has a useful summary of its main trajectory:

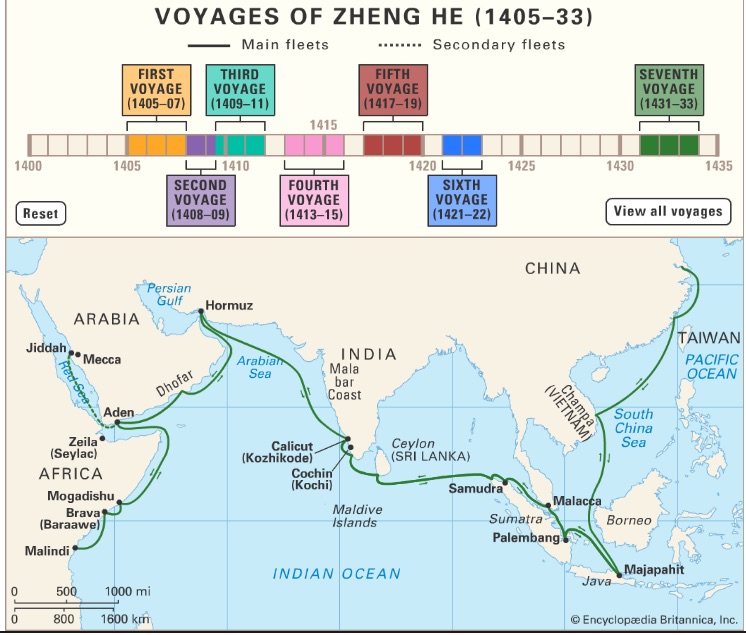

The Hongwu Emperor (r. 1368–1398) attempted to create a society of self-sufficient rural communities ordered in a rigid, immobile system that would guarantee and support a permanent class of soldiers for his dynasty: the empire’s standing army exceeded one million troops and the navy’s dockyards in Nanjing were the largest in the world. He also took great care breaking the power of the court eunuchs and unrelated magnates, enfeoffing his many sons throughout China and attempting to guide these princes through the Huang-Ming Zuxun, a set of published dynastic instructions. This failed when his teenage successor, the Jianwen Emperor, attempted to curtail his uncles’ power, prompting the Jingnan Campaign, an uprising that placed the Prince of Yan upon the throne as the Yongle Emperor in 1402. The Yongle Emperor established Yan as a secondary capital and renamed it Beijing, constructed the Forbidden City, and restored the Grand Canal and the primacy of the imperial examinations in official appointments. He rewarded his eunuch supporters and employed them as a counterweight against the Confucian scholar-bureaucrats. One [of the eunuchs], Zheng He, led seven enormous voyages of exploration into the Indian Ocean as far as Arabia and the eastern coasts of Africa.

The rise of new emperors and new factions diminished such extravagances; the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor during the 1449 Tumu Crisis [this was a military crisis with the Mongols] ended them completely. The imperial navy was allowed to fall into disrepair while forced labor constructed the Liaodong palisade and connected and fortified the Great Wall of China into its modern form. Wide-ranging censuses of the entire empire were conducted decennially, but the desire to avoid labor and taxes and the difficulty of storing and reviewing the enormous archives at Nanjing hampered accurate figures. Estimates for the late-Ming population vary from 160 to 200 million, but necessary revenues were squeezed out of smaller and smaller numbers of farmers as more disappeared from the official records or “donated” their lands to tax-exempt eunuchs or temples. Haijin laws intended to protect the coasts from “Japanese” pirates instead turned many into smugglers and pirates themselves.

By the 16th century, however, the expansion of European trade – albeit restricted to islands near Guangzhou such as Macau – spread the Columbian Exchange of crops, plants, and animals into China, introducing chili peppers to Sichuan cuisine and highly productive maize and potatoes, which diminished famines and spurred population growth. The growth of Portuguese, Spanish, and Dutch trade created new demand for Chinese products and produced a massive influx of Japanese and American silver. This abundance of specie remonetized the Ming economy, whose paper money had suffered repeated hyperinflation and was no longer trusted. While traditional Confucians opposed such a prominent role for commerce and the newly rich it created, the heterodoxy introduced by Wang Yangming permitted a more accommodating attitude. Zhang Juzheng’s initially successful reforms proved devastating when a slowdown in agriculture produced by the Little Ice Age joined changes in Japanese and Spanish policy that quickly cut off the supply of silver now necessary for farmers to be able to pay their taxes. Combined with crop failure, floods, and the Great Plague, the dynasty collapsed before the rebel leader Li Zicheng, who was himself defeated shortly afterward by the Manchu-led Eight Banner armies who founded the Qing dynasty.

I note there the reference to the long voyages of trade and exploration that Admiral Zheng He undertook in early 15th century as “extravagances”. That is notably similar to (though not exactly the same as) the kinds of criticism that, as reported by early 20th-century British William Wilson Hunter, were being lobbed against the voyages of the English East India Company in London in the 1640s. Regarding the 15th-century critics of Zheng He’s voyages, perhaps they had a strong case to argue: The Chinese emperors certainly always did have a very large hinterland they needed to control! (Though it was probably foolish of the Zhengtong Emperor to personally lead his forces into battle against the Mongols in 1449, and get captured on the battlefield there…)

The very damaging capture of the Zhengtong Emperor was not, however, the main trigger for the imperial decision to cut back on the lengthy exploration voyages undertaken by Zheng He and a handful of his contemporaries, which had been taken many years earlier. Zheng himself died in 1433, having undertaken seven amazing voyages of exploration and trade. This WP page on him tells us:

State-sponsored Ming naval efforts declined dramatically after Zheng’s voyages. Starting in the early 15th century, China experienced increasing pressure from the surviving Yuan Mongols from the north. The relocation of the capital to Beijing in the north exacerbated this threat dramatically. At considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions from Beijing to weaken the Mongolians. The expenditures necessary for the land campaigns directly competed with the funds necessary to continue naval expeditions. Further, in 1449, Mongolian cavalry ambushed a land expedition personally led by the Zhengtong Emperor at Tumu Fortress, less than a day’s march from the walls of the capital…

However, missions from Southeastern Asia [who had first been contacted by Zheng He] continued to arrive for decades. Depending on local conditions, they could reach such frequency that the court found it necessary to restrict them. The History of Ming records imperial edicts forbade Java, Champa, and Siam from sending their envoys more often than once every three years.

Throughout the 16th century, Spain was a European power whose leaders also judged they had a large terrestrial hinterland they needed to control and pacify (in continental Europe); and for King Charles and the Philips who followed him those pacifications were similarly extremely costly. The Spanish funded their land expeditions in Europe from the plunder of their colonial expeditions in the Americas, rather than seeing the two options as a kind of zero-sum game. For more than a century that strategy served them very well, though by the 17th century they had started to head into decline.

As for the English in the 1640s, safeguarding the rule at home certainly was a challenge, but not one that called for the fielding and financing of huge land armies on the scale of China vs. the Mongols, or Spain vs. its European enemies. In the end, for both the King’s side and the Parliamentary side in England, prevailing in their fight at home called much more on diplomatic skill and the ability to establish and maintain a well-functioning administration than on the need to find massive finances for a massive land army. For the leaders on both those sides in the English contest, the already existing transoceanic imperial system was probably seen neither as a burden (as in early 15th-century China) nor as a financial necessity, as for Habsburg Spain. Both sides in the English contest probably saw the transoceanic empire as an instrument of actual or potential power in their contest, but probably not a very big one. In the case of the Puritan colonies in Massachusetts, clearly they were all strong supporters of the Parliament side, and the EIC’s governors and decision-makers almost certainly felt happier with Parliament/Cromwell than they did with the King…

In 1644, the internal conflict in England was still years away from being resolved. In China, an entire new dynasty was busy installing itself. But the decision that a series of Ming emperors had taken 230 years earlier to disband the country’s long-haul naval forces, and plow resources instead into maintaining a huge land army and extensively repairing the Great Wall, was with every decade that passed in the 17th century leaving China more vulnerable to rapacity of the European powers that now had very capable long-haul navies…