In 1643 CE I’ll look at England’s continuing King vs. Parliament civil war, and its many repercussions including on Ireland, the Anglo colonies in North America, and the East India Company (EIC.) The other significant story is an attempt the Dutch swashbucklers made to take a chunk of Chile from Spain.

I’ll come to those stories lower down. First, four non-trivial side-eddies in the world history of 1643:

1. France’s King Louis XIII dies

Louis died of tuberculosis in May 1643.His four-year-old son Louis XIV succeeded him. Per the dad’s will, so long as the son was a minor, power was to be exercised by a regency council headed by XIII’s widow, Anne of Austria. But Anne quickly did away with the idea of a “council” and became sole regent. Then, per Wikipedia, she, “entrusted the government to the chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, who was a protégé of Cardinal Richelieu and figured among the council of the regency. Mazarin left the Hôtel Tubeuf to take up residence at the Palais Royal near Queen Anne. Before long he was believed to be her lover, and, it was hinted, even her husband.” Louis XIV, later known as “the Sun King” would have a reign of 72 years and 110 days.

(The banner image above is a painting of (l. to r.) Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Queen Anne.)

2. Portugal’s King John executes his Prime Minister

Francisco de Lucena had been a prominent and trusted official in the Spain-led Iberian Union for many years before 1640, when the Portuguese nobles seceded and declared John IV the king of independent Portugal. Francisco reportedly had ties to John’s family dynasty and was appointed by John to be his Secretary of State (that is, in modern parlance, his prime minister.) During his three years in office he pursued a fairly pro-Spanish policy and made powerful enemies in Lisbon, including the Jesuits. In 1642 he was accused of treason, removed from his office, and imprisoned. In April 1643 he was beheaded, reportedly by the same cleaver used in some of the executions he himself had earlier ordered. Would independent Portugal be able to build and keep a stable governance system? Let’s see.

3. Spain’s king also ditches his PM

We’d met King Philip IV’s key advisor and longtime prime minister Gaspar de Guzmán, the Count-Duke of Olivares, earlier. Things, obviously, had not been going well for Spain what with the Portuguese secession and the continuation of the rebellion in in Catalonia, etc. So in January 1643, this happened, per Stanley Payne’s A History of Spain and Portugal, p.315-16:

Olivares recognized the failure of state policy and resigned… leaving Felipe IV resolved to serve as his own chief minister, encouraged by his correspondence with the noted mystic Sor María de Agreda. He had a quick enough mind but was simply too self-indulgent and undisciplined, given to a lechery remarkable even among seventeenth-century kings, and by mid-1643, Olivares had been replaced with a new valido [trusted advisor], his own nephew (and enemy), the Conde de Haro…

The resignation of Olivares brought no real change in policy or problems. The financial burden continued to mount. By 1644, the crown’s income was pledged four years in advance, bringing further exactions on the shriveled Castilian economy. Still, there was no compromise in the objectives of royal policy. In 1643, an underequipped Spanish army was destroyed with great loss at Rocroi near the northern French border, the first disastrous field defeat suffered by Spanish infantry since the union of the crowns.

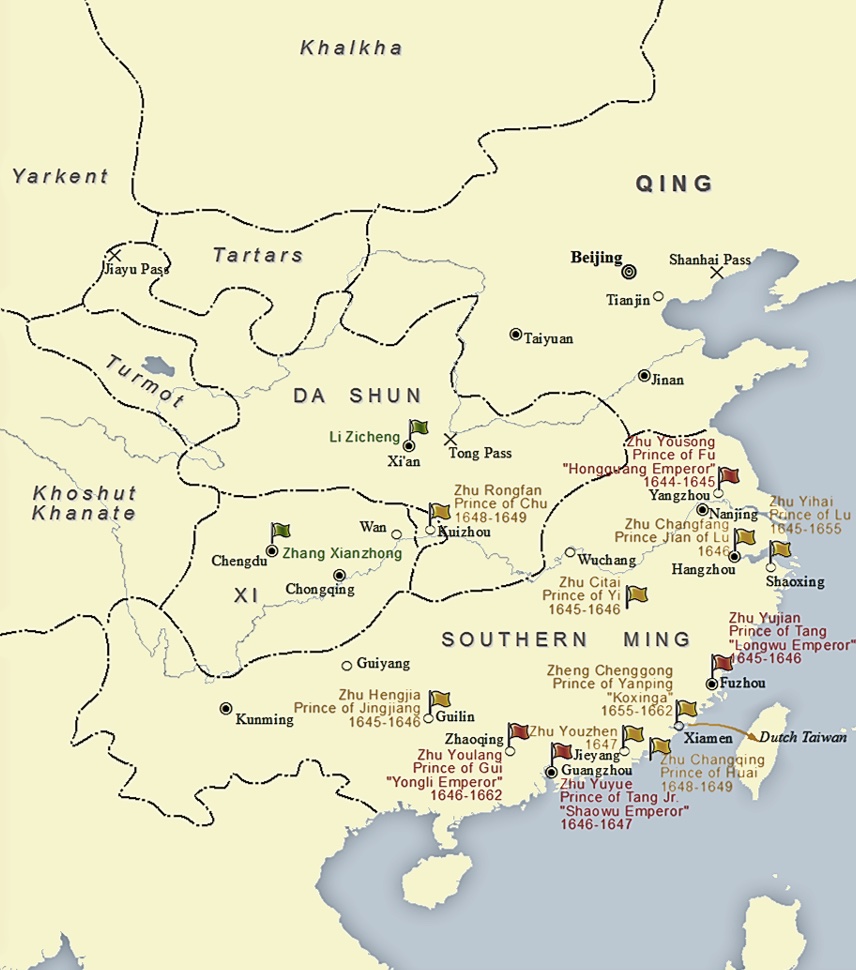

4. A momentous succession in China

This excellent map by WP contributor SY gives a late-1644 snapshot/sketch of the situation in China as the Ming dynasty crumbles ever faster. You can see areas controlled (more or less) by Li Zicheng, whom we met last year, along with two other anti-Ming forces, the Xi and the Qing.

In 1643, as the Qing continued to expand–they had not yet reached Beijing– their capable leader Hong Taiji died. Like France, the Qing would also get a preschool-age monarch. English-WP tells us how it happened:

Hong Taiji died on 21 September 1643 just as the Qing was preparing to attack Shanhai Pass, the last Ming fortification guarding access to the north China plains. Because he died without having named an heir, the Qing state now faced a succession crisis. The Deliberative Council of Princes and Ministers debated on whether to grant the throne to Hong Taiji’s half-brother Dorgon – a proven military leader – or to Hong Taiji’s eldest son Hooge. As a compromise, Hong Taiji’s five-year-old ninth son Fulin was chosen, while Dorgon – alongside Nurhaci’s nephew Jirgalang – was given the title of “prince regent”. Fulin was officially crowned emperor of the Qing dynasty on 8 October 1643 and it was decided that he would reign under the era name “Shunzhi.” A few months later, Qing armies led by Dorgon seized Beijing, and the young Shunzhi Emperor became the first Qing emperor to rule from that new capital. That the Qing state succeeded not only in conquering China but also in establishing a capable administration was due in large measure to the foresight and policies of Hong Taiji. His body was buried in Zhaoling, located in northern Shenyang.

5. Dutch capture Valdivia, Chile

A few decades earlier, Valdivia had been one of the “Seven Cities” (Spanish colonial settlements) that the Spanish had lost during an early phase of the long-roiling resistance movement of the feistily Indigenous Mapuche people. In 1642, the Dutch East India Company joined with the Dutch West Indies Company (VOC) in organising an expedition under Hendrik Brouwer to Chile to establish a (doubtless well-armed) trading base at the long-abandoned site of Valdivia. Brouwer was an experienced navigator and administrator who had been the VOC/Dutch Governor-General of the East Indies in the 1630s. My thought is that the two companies probably planned this joint mission with the aim of then being able to connect the Dutch positions in Brazil and Chile, across the Pacific, with the strong positions the VOC already had in the East Indies.

English-WP tells us this about the expedition:

The expedition was small compared to the Dutch forces that had taken over much of Portuguese Brazil, but it was anticipated that it would be supported by the fiercely anti-Spanish Mapuche-Huilliche confederation once it reached Chile. The expedition was issued formal instructions to capture the gold mines, capture Valdivia, make alliances with the indigenous peoples, the Mapuches and the Huilliches, and to explore Santa María Island. Except for Brouwer and other leaders, the true objectives were not known to the participants of the expedition; they were led to believe that it was a raiding and trading voyage.

Brouwer and a small fleet of an unknown number of vessels left the Netherlands on 6 November 1642 with 250 men.The fleet called at Mauritsstad (modern Recife) in Dutch Brazil where John Maurice of Nassau resupplied it and provided an additional 350 men. As the expedition was aimed at cold southern latitudes woolen clothes were rationed among the crew and passengers.

Well, they had lots of adventures as they rounded the southern tip of South America. Then, shortly before they got to Valdivia, Brouwer died. The expedition nonetheless proceeded:

The expedition set sail for Valdivia on 21 August [1643] and reached their destination within three days. Herckmans arrived at the mouth of Valdivia River in Corral Bay on 24 August. From there the Dutch had difficulties sailing up the Valdivia River to the site of Valdivia as they lacked experience of sailing on rivers… The ruins of Valdivia were reached by the two remaining ships four days later on 28 August. Upon arrival curious Mapuches gathered to watch them. The ships were surrounded by canoes. Reportedly some natives boarded the ships and stole iron objects, including a valuable compass.

In Valdivia the Dutch established a new settlement, which [new expedition leader Elias] Herckmans named Brouwershaven after Brouwer. On August 29 the Dutch had met with local tribal leader Manquipillan and his host. In the meeting the Dutch held a long discourse in which they highlighted what they believed was the common enmity to Spain; later gifts were given by the Dutch. At the end a friendly relationship had been established with Manquipillan. A new solemn meeting was held on September 3, with an even greater assistance. In this meeting a formal alliance was established between the Dutch and local Mapuches. Local Mapuches promised to help the Dutch with the construction of a fort and to give provisions for the nascent colony. The embalmed body of Brouwer was buried in Valdivia on September 16 there.

It did not go well. The Mapuches were far more sophisticated in their understanding of the real aims of “visiting” Europeans than had been most of the rulers the Dutch had encountered in the East Indies.

In Valdivia the Dutch begun the construction of a fort. A major setback to the Dutch was that they had also failed to find the anticipated gold mines.The Mapuches begun to realise the Dutch had no plans of leaving and their search for gold caused suspicion, leading the locals to halt their deliveries of food. The Mapuche chief Juan Manqueante, from Mariquina, who was in friendly terms with the Dutch staunchly refused them to access the gold mines of Madre de Dios in his lands. Manqueante told the Dutch of his people’s negative experiences of Spanish gold mining. Other contributing factors behind the cold attitude of local Mapuches may have been the Dutch rhetoric about war with Spain, which may have upset the Mapuches of Valdivia who had lived in peace for about forty years and the fact that local Mapuches may not have seen any significant difference between the Dutch and Spanish. Local Mapuches justified not sending provisions by claiming they had not enough food for themselves. The Dutch were demoralised by the scarcity of food and lack of comfort. A mutiny begun to smolder and some Dutch left the encampment at night for the woods with the final aim of surrendering to the Spanish in Concepción.

Desertions from the Dutch forces continued… and meantime the local Spanish had been able to regroup some. Herckmans decided to abandon the project and take his surviving people back to Brazil:

Yet before leaving Valdivia the Dutch called local Mapuches for a meeting where Herckmans made them aware that treacherous attitudes had not passed inadvertently. Nevertheless, following this the Dutch gave away some of their antique weapons and armour including chain mails and morions in exchange for provisions. Likely it was also their hope these weapons would be put into use against the Spanish.

Juan Manqueante provided relief to the hungry Dutch in the form of cattle. This relief was only temporary since Manqueante probably considered it a farewell gift. Before leaving, Manqueante was contacted by Herckmans to let him know that the Dutch intended to return with 1,000 African slaves to take care of mining and agriculture in order to leave the indigenous peoples free of forced labour. This promise was never fulfilled.

English-WP tells us that after 1643, “The Spanish resettled Valdivia and began the construction of an extensive network of fortifications in 1645 to prevent a similar intrusion. Although contemporaries considered the possibility of a new incursion, the expedition was the last one undertaken by the Dutch on the west coast of the Americas.”

(I’m still getting my head around Herckmans’s promise to return with 1,000 enslaved Africans— and the assumption he presumably harbored that his Mapuche host would think that a good idea… )

6. England’s civil war and its ramifications

China was not the only country suffering from civil war in 1643. So, on a much smaller scale, was England. King Charles I had spent the winter of 1642-43 holed up in Oxford. In February 1643 his wife Henrietta Maria was able to return to England with the weapons shipment she had procured, presumably from the Spanish. She sailed into Bridlington on the East Yorkshire coast, made her way to York, then traveled overland with an escort of 5,000 cavalry to Oxford, arriving in mid-July.

The Parliamentarian side was meanwhile headquartered in London, strong at nearly all the country’s ports and in many other parts of the country, too. Each side, King and Parliament, tried to work with allies in Scotland and Ireland to be able to increase its raw power and its political leverage. In England, the front-lines moved back and forth and it was essentially a stalemate for a couple of years.

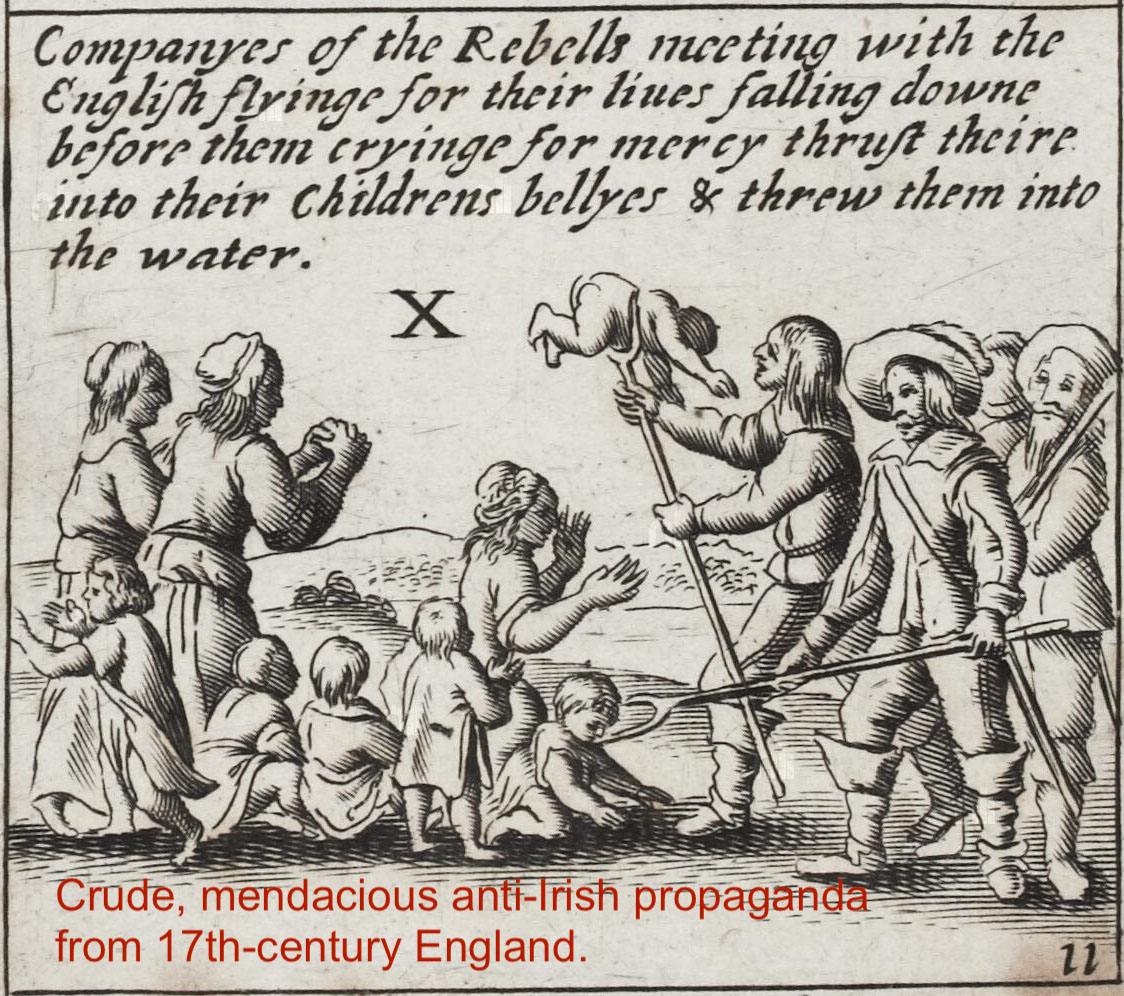

In Ireland, the mainly Catholic coalition of the Confederacy kept up its fight against the loyalist military sent by Charles. In March, the loyalists had a significant victory in a battle at Ballinvegga in the southeast. English-WP tells us this:

After the battle, it was said of the terrible damage caused by the artillery “what goodlie men and horses lay there all torn and their guttes lying on the ground – armes cast away and strewed over the fields.” It was estimated that the Confederates lost approximately 500 men in the battle compared to 20 men slain for the Royalists…

[Loyalist commander the Marquis of] Ormond returned safely to Dublin without further harassment from the Confederates. Even though Ormond had decisively defeated the Confederates at Ballinvegga, he was criticized by his rivals for not capturing New Ross and not totally destroying the Confederates’ Leinster Army.

So what was happening in London and the other Parliament-held areas of England meanwhile? Clearly, a huge amount of political, religious, and religio-political ferment. An incomplete list of the numerous Protestant sects that emerged in the ferment of those war years would have to include the Levellers, the Diggers, the Ranters, the Seekers, the Quakers– and even two groups called the Muggletonians and the Grindletonians. These new sects added to the non-Anglican Protestant groups that had anyway previously existed in England, like the Brownists and their descendants the Puritans. (And we have seen in early years how the Puritans were divided among themselves, between the Separatists and the Antinomians, or whatever.) It is all pretty head-spinning to keep track of.

6a. Roger Williams in London

In 1643 enters this scene Roger Williams, the Puritan from London via Massachusetts who had then left to form his own (Indigenous-respecting) Puritan colony in the terrain of today’s Rhode Island. Williams had traveled back to London in 1643 to get a charter for his new colony. This, from WP:

Williams arrived in London in the midst of the English Civil War. Puritans held power in London, and he was able to obtain a charter through the offices of Sir Henry Vane the Younger, despite strenuous opposition from Massachusetts’ agents. His first published book ‘A Key into the Language of America‘ proved crucial to the success of his charter, albeit indirectly. Published in 1643 in London, the book combined a phrase-book with observations about life and culture as an aid to communicate with the Native Americans of New England. In its scope, the book covered everything from salutations to death and burial. Williams also sought to correct the attitudes of superiority displayed by the colonists towards Native Americans:

Boast not proud English, of thy birth & blood;

Thy brother Indian is by birth as Good. Of one blood God made Him, and Thee and All,

As wise, as fair, as strong, as personal.

… Williams secured his charter from Parliament for Providence Plantations in July 1644, after which he published his most famous book The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience.

Tenent is an archaic spelling of “Tenet”. This book was a powerful appeal for the separation of church and state– and it did not go down well with the Puritans of London:

The publication produced a great uproar; between 1644 and 1649, at least 60 pamphlets were published addressing the work’s arguments. Parliament responded to Williams on August 9 1644, by ordering the public hangman to burn all copies. By this time, however, Williams was already en route to New England, where he arrived with his charter in September.

6b. A colonial confederation in New England

While Williams was in London, the leaders of Massachusetts and other “New England” colonies were trying to form a confederation. English-WP tells us how that went:

The United Colonies of New England, commonly known as the New England Confederation, was a short-lived military alliance of the New England colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Saybrook (Connecticut), and New Haven formed in May 1643. Its primary purpose was to unite the Puritan colonies in support of the church, and for defense against the American Indians and the Dutch colony of New Netherland… Its charter provided for the return of fugitive criminals and indentured servants, and served as a forum for resolving inter-colonial disputes. In practice, none of the goals were accomplished.

The confederation was… dissolved after numerous colonial charters were revoked in the early 1680s.

6c. The civil war and the EIC

I realize this topic deserves much more attention that than I’m giving it here but this what I have time for: I’ll present what historian William Wilson Hunter (WWH) has to say about it in Appendix I of his 1907 book The European Struggle for Indian Supremacy in the Seventeenth Century, which is basically an always sympathetic study of the EIC’s operations in those years.

WWH seemed to have been quite a fan of Oliver Cromwell! But he hasn’t really entered our main narrative yet, since in 1643 he was still rising up the somewhat disordered ranks of the Parliamentary forces’ high command…

WWH wrote (pp.253-57):

But before [Cromwell’s] strong hand could make its weight felt, a period intervened when there was no king in Israel. From the Battle of Edgehill, in October, 1642, to the last scene outside Whitehall in January, 1649, Charles, whatever may have been his faults, cannot be held accountable for the distresses of the East India Company. One Parliament, with the king, a majority of the Lords, and a minority of the Commons, sat at Oxford. Another Parliament, with a majority of the Commons and a minority of the Lords, sat at Westminster. It was with this London Parliament that the Company had to reckon. The Houses at Westminster could levy contributions in the capital, they collected the customs, and controlled the shipping in the Thames. In 1643 they put a curb on the Royalist members of the Company by demanding a forced loan of its ordnance, “for the fortifying of the bulwarks, now in preparation for the security of the City.” On its refusal, the Commons declared they would grant an order to the Committee of Fortifications to take them. So the cannon had to be given up, and the next year the Company petitioned for payment or their return.

The London Parliament was, in truth, in no mood to tolerate a king’s faction within the liberties of the City. In 1643 it cashiered the Company’s governor, sequestrated moneys due to Royalists at the India House, and forbade any dividends to be paid until the directors had had an interview with a committee of the Lords and Commons. Later in the year, the Parliamentary Government demanded a loan of £10,000, and the Company was glad to get off for half that sum. By 1644 the Royalist party in the Company was cowed, and the chief officers of its ships had taken the Solemn League and Covenant.

This coercion cost the Company dear. It had lately opened houses in Italy to dispose of its Indian goods, almost unsalable amid the troubles at home, and in 1645 one of its Royalist members, Sir Peter Rychaut, revenged his sequestrations in England by seizing three hundred bags of its pepper in Venice. Its captains, when clear of the Thames, were sometimes difficult to control. Captain Mucknell of the ship John, for example, carried his ship into Bristol and delivered it to the king’s general. He then sallied forth with three armed vessels to waylay other Indiamen, and the Company was advised to despatch two nimble pinnaces to scout among the Western Islands or Azores and warn its homeward-bound vessels of their danger.

Amid this confusion, the Company still tried to make a show of trade. With no hope from the king, by whose charter it existed, and in little favour with Parliament, it found its position almost as isolated as that of its servants in India. Like them, it evoked from the sense of desertion a resolve to rely upon itself. It entered, as we shall see, into direct negotiations with the Portuguese ambassador in London, and it almost succeeded in coming to an arrangement with the Dutch. It also began to strike out new trade methods. In 1640, with the help of royal promises, it had tried to raise fresh capital under the name of the Fourth Joint Stock. But the public had lost confidence, and with the shares selling as low as sixty per cent., the money could not be obtained.

Yet individual expeditions, if conducted without a dead outlay on factories, forts, and a permanent staff in India, yielded large profits. Laying aside for the time the project of a Fourth Joint Stock, some of its members subscribed in 1641 for a Particular Voyage, which should engage no servants in the East, but pay a commission to the Third Joint Stock for selling its goods and collecting a return cargo. Others began to take heart and got together a small nucleus for the Fourth Joint Stock. This double organization of individual voyages and a general stock led to grave difficulties, as it tried to combine the early plan of Separate Voyages with the Joint Stocks, or series of voyages, which had superseded them. Yet it enabled the Company to struggle through the civil wars without altogether losing its continuity of trade…