Here are the headlines of what was happening in (mainly) West-European imperialisms in 1638 CE:

1. Dutch VOC activities in Mauritius, Sri Lanka

In 1507 a Portuguese squadron made the first European contact with Mauritius, a small island group in the Indian Ocean east of today’s Sri Lanka and established a small and short-lived base there. (Arab sailors and perhaps indigenous peoples had been there before.) Later, in 1598, Dutch sailors came there and gave the island its name, in honor of Maurice of Nassau.

Now, in 1638, the Dutch established a longer-lasting settlement on the island. English-WP tells us what they did there:

they exploited ebony trees and introduced sugar cane, domestic animals and deer. It was from here that Dutch navigator Abel Tasman set out to seek the Great Southern Land, mapping parts of Tasmania, Aotearoa/New Zealand and New Guinea. The first Dutch settlement lasted 20 years. In 1639 slaves arrived in Mauritius from Madagascar. The Dutch East India Company brought them to cut down ebony trees and to work in the new tobacco and sugar cane plantations. Several attempts to establish a colony permanently were subsequently made, but the settlements never developed enough to produce dividends, causing the Dutch to abandon Mauritius in 1710.

Meantime, in near-ish Sri Lanka/ Ceylon, 1638 saw the conclusion by Kandy’s King Rajasinha II of a treaty with the VOC to “get rid of the Portuguese who ruled most of the coastal areas.” There followed a conflict between the Dutch and Portuguese in Kandy, in which the Dutch were victorious. But then, they refused to leave! Rajasinha got buyers’ remorse. This page on WP tells us, “The alliance of 1638 came to an abrupt end and Kandy launched into what was to be a hundred years of intermittent warfare with the Dutch.”

2. Dutch clergyman justifies enslavement, war

Godfried Udemans was one of the influential Calvinist theologians of the Dutch province of Zeeland. In 1638, he published theological guide called ’t Geestelyck roer van ’t coopmaans schip, which Dutch scholar Joris van Eijnatten writes (PDF download) is best translated as The spiritual helm of the merchant’s vessel. The book’s subtitle, van E adds, explains Udemans’ choice of metaphor:

that is: a faithful account of how a merchant and seafaring trader should conduct himself in his actions, in times of peace and war, with respect to both God and people, on water and on land, and especially among the heathens in the East and West Indies: for the glory of God, the foundation of His congregations, and the salvation of His souls: and also for the temporal well-being of the fatherland and his family.

I am still reading and digesting van Eijnatten’s article on Udemans, which gives an extensive digest of the contents of The Spiritual Helm. Van E notes that Udemans referred frequently to his countryman Hugo Grotius’s writings on “Just War” issues (in which Grotius had justified the taking of enslaved people as booty), but that he seemed to be more supportive than Grotius of the concept of a “war without restraint”– always on “Godly” grounds, of course.

Van E describes Udemans’s views on ius in bello issues as follows::

A war, he states, ought to be waged in a just manner, according to divine and human laws. For knowledge of the divine laws, Udemans refers his Christian soldier to Deut. 20:1 to 23:9. This notorious pericope includes passages that justify unrestrained warfare on religious grounds. The following is one of them:

“And if it will make no peace with thee, but will make war against thee, then thou shalt besiege it: And when the LORD thy God hath delivered it into thine hands, thou shalt smite every male thereof with the edge of the sword: But the women, and the little ones, and the cattle, and all that is in the city, even all the spoil thereof, shalt thou take unto thyself; and thou shalt eat the spoil of thine enemies, which the LORD thy God hath given thee. Thus shalt thou do unto all the cities which are very far off from thee, which are not of the cities of these nations. But of the cities of these people, which the LORD thy God doth give thee for an inheritance, thou shalt save alive nothing that breatheth: But thou shalt utterly destroy them (…). (Deut 20:12-17)”

At the very least, this passage legalizes the unrestrained killing of males and the unreserved taking of spoils, including women, children and cattle.

In another reference to Udemans’ book that I am trying to track down, Udemans is described as justifying bondage for “heathens”– but he “urged that they be well treated and educated in true Christian principles, with freedom possible after seven years of service.” (Gerbner, 2018, p.24)

I continue to be interested in this matter of the influence that religion had on the Netherlands’ empire-building projects in that era. As of now, I don’t think it had anywhere near as great an influence for the profit-seekers of the two great Dutch trading/raiding companies as militant Catholicism had in the building and maintenance of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, or as strongly-pursued Puritanism had on the development of English colonies in North America. But let us see…

3. News from colonial North & Central America

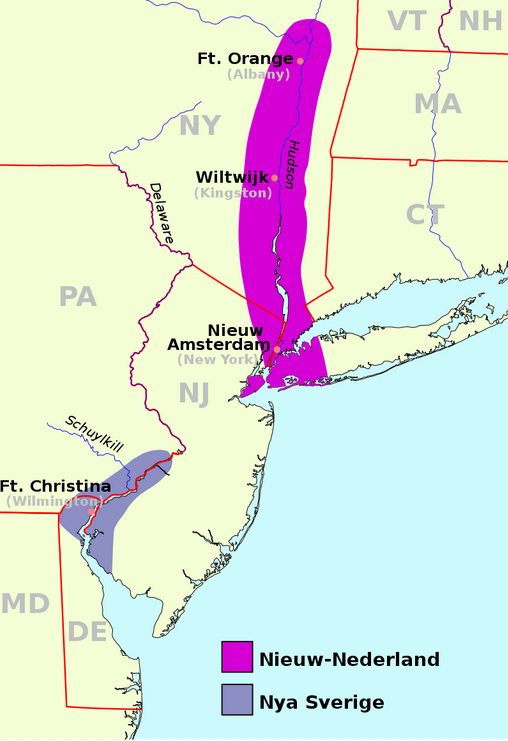

In 1626, Sweden’s ambitious and capable King Gustavus Adolphus granted a charter to a group of adventurers called the “Swedish South Company” to establish and run a Swedish colony in the Americas. Gustavus Adolphus died in 1632. In late 1637, a successor to the SSC called the “New Sweden Company” was finally able to mount its first expedition, which was to the valley of the Delaware River; and it arrived in late March 1638. The expedition leader was Peter Minuit, the disaffected former governor of New Netherland.

English-WP tells us this about what ensued:

They built a fort in Wilmington which they named Fort Christina after Queen Christina. In the following years, the area was settled by 600 Swedes and Finns, a number of Dutchmen, a few Germans, a Dane, and at least one Estonian, and Minuit became the first governor of the colony of New Sweden. He had been the third Director of New Amsterdam, and he knew that the Dutch claimed the area south to the Delaware River and its bay. The Dutch, however, had pulled back their settlers from the area after several years in order to concentrate on the settlement on Manhattan Island.

Governor Minuit landed on the west bank of the river and gathered the sachems of the Delawares and Susquehannocks. They held a conclave in Minuit’s cabin on the Kalmar Nyckel, and he persuaded them to sign deeds which he had prepared to solve any issue with the Dutch. The Swedes claimed that the purchased land included land on the west side of the South River from just below the Schuylkill River in Philadelphia, southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware, and coastal Maryland. Delaware sachem Mattahoon later claimed that the purchase only included as much land as was contained within an area marked by “six trees”, and the rest of the land occupied by the Swedes was stolen.

Willem Kieft [the Director of New Netherland] objected to the Swedes landing, but Minuit ignored him since he knew that the Dutch were militarily weak at the moment. Minuit completed Fort Christina in 1638, then sailed for Stockholm to bring the second group of settlers. He made a detour to the Caribbean to pick up a shipment of tobacco to sell in Europe in order to make the voyage profitable. However, he died on this voyage during a hurricane at St. Christopher in the Caribbean. The official duties of the governor of New Sweden were carried out by Captain Måns Nilsson Kling, until a new governor was selected and arrived from Sweden two years later.

Spoiler alert here: “New Sweden” lasted only 17 years. In 1655, the Dutch came down from New Netherland and took it over.

Meantime in Central America:

In 1638, the English (not clear which entity?) established a colony called Belize on the Caribbean coast of Central America. English-WP tells us this:

Belize City was founded as “Belize Town” in 1638 by English lumber harvesters. It had been a small Maya city called Holzuz. Belize Town was ideal for the English as a central post because it was on the sea and a natural outlet for local rivers and creeks down which the British shipped logwood and mahogany. Belize Town also became the home of the thousands of [enslaved Africans] brought in by the English… to toil in the forest industry.

Because of all the shipbuilding the large, Europe-based maritime empires were doing, sturdy lumber was already becoming an increasingly rare commodity in their home territories and was thus emerging as key “strategic” commodity for them. (See also, Mauritius, above.)

4. News from land-based empires

Well, as alert longer-time readers of P500Years will know, I decided a while back not to devote much attention to the big land-based empires in existence in the 17th century. But 1638 was definitely a bad year for the Safavids. To their northwest, they lost Baghdad to the Ottoman Empire, and to their south they lost Kandahar to the Mughals.

The Safavid Shah at the time was variously known as Sam Mirza or, his dynastic name, Shah Safi. English-WP tells us this about him:

Safi was crowned on 28 January 1629 at the age of eighteen. He ruthlessly eliminated anyone he regarded as a threat to his power, executing almost all the Safavid royal princes as well as leading courtiers and generals. He paid little attention to the business of government and had no cultural or intellectual interests (he had never learned to read or write properly), preferring to spend his time drinking wine or indulging in his addiction to opium. Supposedly, however, he abhorred tobacco smoke as much as his grandfather did, going as far as to have those caught smoking tobacco in public killed by pouring molten lead in their mouths.

The banner image above is a detail from a painting of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, which had somehow (!) ended up in the British royal family’s library. The whole of this book of miniatures can be viewed or even downloaded here.