1637 CE saw three significant developments in the history of empires, and two noteworthy but less significant ones. The significant developments were:

- The bursting of the tulip investment bubble in Amsterdam (and what it tells us about the origins of finance capitalism)

- English colonists in Connecticut genocided the indigenous Pequots at Mystic River

- A Chinese savant published an encyclopedia describing technological processes new and old.

Scroll on down to learn more about those three. The two “merely noteworthy” developments were these:

- English Captain John Weddell, who had earlier sailed for both the Muscovy Company and the EIC, had broken angrily with the EIC and was the chief captain on the EIC-challenging expedition sent to the Indian Ocean by the Courteen Association in 1636. In 1637, he had reached the shores of China and tried to start a trading venture in Canton. He took with him “38,421 pairs of eyeglasses, perhaps the first recorded European-made eyeglasses to enter China.” But that venture failed, reportedly due to “Portuguese intrigues.”

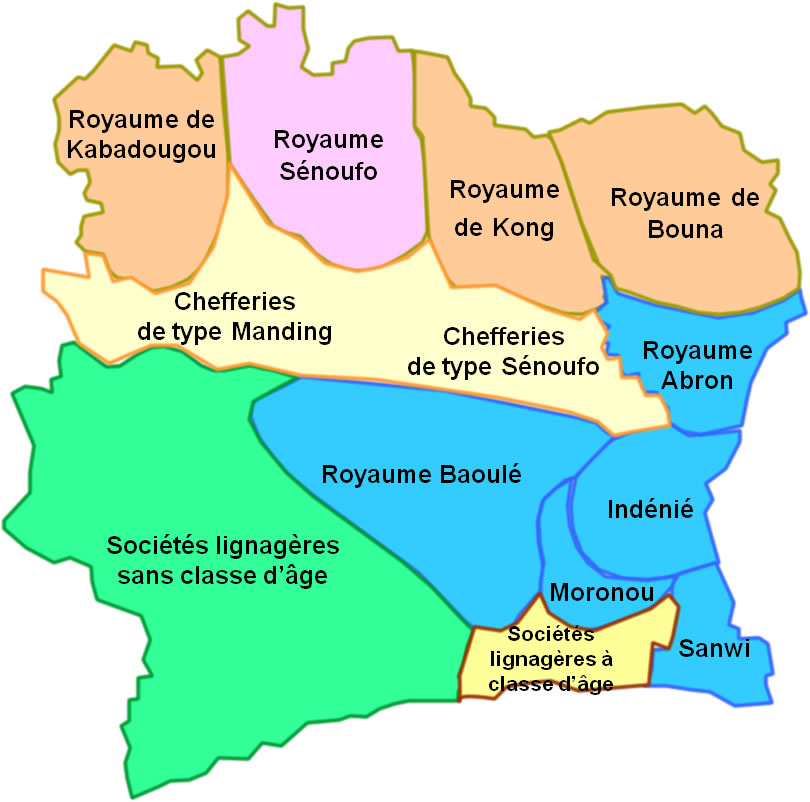

- In 1637, a French “mission” was established at Assinie in today’s Ivory Coast, but it didn’t last long. French-WP tells us: “Assinie (autrefois Issiny) fut le premier comptoir de la côte ivoirienne, bien qu’il ne reste plus aujourd’hui aucun vestige de cette époque. Dès 1637, cinq missionnaires capucins, venus de Saint-Malo pour évangéliser, s’y installent. Le climat et les maladies les font repartir rapidement, trois d’entre eux perdent la vie et les deux autres migrent au Ghan, précisément à Axim.” No French returned there until 1687, when, “des missionnaires et des commerçants français s’installent sur le site d’Assinie, à l’extrémité est du littoral, vers la Côte de l’Or, mais ils repartent en 1705 après avoir construit et occupé le Fort Saint-Louis, premier établissement français d’Asini, de 1701 à 1704. La raison : le commerce des esclaves contre les céréales ne rapportant pas assez.”

On to tulips, genocide, and an encyclopedia.

Bursting of Dutch tulip bubble tells us about link of empire and finance capitalism

Back in 1593, Dutch horticulturalist Carolus Clusius had planted the first tulip bulbs ever planted in Western Europe. Almost certainly imported from Constantinople, where they were native. (So the whole presence of tulips in Netherlands is a result of early globalization from the get-go.)

People in the newly independent Dutch UP’s loved these new flowers, which speedily became much sought after, and very valuable. Tulips are very hard to grow from seed, generally being propagated through storage and replanting of the bulbs. The most popular varieties were the variegated kind, which the Dutch horticulturalists discovered was caused by something called the “tulip breaking virus” (since it breaks down the colors), which slows down propagation via bulbs/buds.

English-WP tells us that, “tulips rapidly became a coveted luxury item, and a profusion of varieties followed.” Also, this:

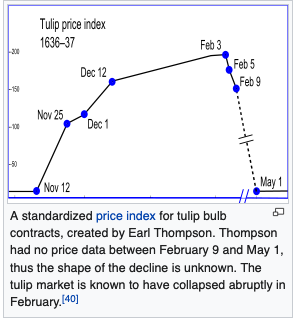

During the plant’s dormant phase from June to September, bulbs can be uprooted and moved about, so actual purchases (in the spot market) occurred during these months. During the rest of the year, florists, or tulip traders, signed contracts before a notary to buy tulips at the end of the season (effectively futures contracts). Thus the Dutch, who developed many of the techniques of modern finance, created a market for tulip bulbs, which were durable goods. Short selling was banned by an edict of 1610, which was reiterated or strengthened in 1621 and 1630, and again in 1636. Short sellers were not prosecuted under these edicts, but futures contracts were deemed unenforceable, so traders could repudiate deals if faced with a loss.

As the flowers grew in popularity, professional growers paid higher and higher prices for bulbs with the virus, and prices rose steadily. By 1634, in part as a result of demand from the French, speculators began to enter the market. The contract price of rare bulbs continued to rise throughout 1636, but by November, the price of common, “unbroken” bulbs also began to increase, so that soon any tulip bulb could fetch hundreds of guilders. That year the Dutch created a type of formal futures market where contracts to buy bulbs at the end of the season were bought and sold. Traders met in “colleges” at taverns and buyers were required to pay a 2.5% “wine money” fee, up to a maximum of three guilders per trade. Neither party paid an initial margin, nor a mark-to-market margin, and all contracts were with the individual counter-parties rather than with the Exchange. The Dutch described tulip contract trading as windhandel (literally “wind trade”), because no bulbs were actually changing hands. The entire business was accomplished on the margins of Dutch economic life, not in the Exchange itself.

By 1636, the tulip bulb became the fourth leading export product of the Netherlands, after gin, herrings, and cheese. The price of tulips skyrocketed because of speculation in tulip futures among people who never saw the bulbs. Many men made and lost fortunes overnight.

Tulip mania reached its peak during the winter of 1636–37, when some bulb contracts were reportedly changing hands ten times in a day. No deliveries were ever made to fulfill any of these contracts, because in February 1637, tulip bulb contract prices collapsed abruptly and the trade of tulips ground to a halt.

“Tulip mania” in Amsterdam, in the years leading up to 1637, was certainly a real thing, much commented upon at the time. The banner image at the top of the page is a satirical view of it painted by Jan Breughel; Hendrik Pot painted the satire shown here in 1640.

Over the centuries since then economists have argued over how widespread tulip mania was and how devastating the bursting of the bubble ended up being. What was clear, then and now, was that in the early 17th century Amsterdam was witnessing very intense interest in securing profits through share-trading and that practice had grown greatly in popularity in the city hand-in-hand with the founding and operations of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (GWC)… More on this, later.

Connecticut colonists genocide Pequots at Mystic Fort

This, from English-WP:

The Pequots were the dominant Native American tribe in the southeastern portion of Connecticut Colony, and they had long competed with the neighboring Mohegan and Narragansett tribes. The European colonists established trade with all three tribes, exchanging European goods for wampum and furs. The Pequots eventually allied with the Dutch colonists, while the Mohegans and others allied with the New England colonists.

So guess what, conflicts grew up between the English settlers and the Pequots and of course the English settlers exploited older rivalries that the other local Natives had with the Pequots. Food was also running short because in 1635 a hurricane had wiped out many of the harvests.

Then this (from WP— my emphases throughout):

The Connecticut [settler-]towns raised a militia commanded by Captain John Mason consisting of 90 men, plus 70 Mohegans under sachems Uncas and Wequash. Twenty more men under Captain John Underhill joined him from Fort Saybrook. Pequot sachem Sassacus, meanwhile, gathered a few hundred warriors and set out to make another raid on Hartford, Connecticut.

At the same time, Captain Mason recruited more than 200 Narragansett and Niantic warriors to join his force. On the night of May 26, 1637, the Colonial and Indian forces arrived outside the Pequot village near the Mystic River. The palisade surrounding the village had only two exits. The Colonial forces attempted a surprise attack but met stiff Pequot resistance. Mason gave the order to set the village on fire and block off the two exits, trapping the Pequots inside. Many who tried climbing over the palisade were shot; most who succeeded in getting over were killed by the Narragansett fighters. The colonists reported that only five Pequots had successfully escaped the massacre and seven were taken prisoner. When a Pequot fell, the Mohegans would cry out, run and fetch his head. Many scalps were taken and sent back as trophies. This was the first example of total war by the colonists in the new world.

WP describes the aftermath thus:

Estimates of Pequot deaths range from 400 to 700, including women, children, and the elderly. The colonists suffered between 22 and 26 casualties with two confirmed dead. Approximately 40 Narragansett warriors were wounded as the colonists mistook many of them for Pequots. The massacre effectively broke the Pequots, and Sassacus and many of his followers were surrounded in a swamp near a Mattabesset village called Sasqua. The battle which followed is known as the “Fairfield Swamp Fight”, in which nearly 180 warriors were killed, wounded, or captured. Sassacus escaped with about 80 of his men, but he was killed by the Mohawks, who sent his scalp to the colonists as a symbol of friendship.

The Pequot numbers were so diminished that they ceased to be a tribe in most senses. The treaty mandated that the remaining Pequots were to be absorbed into the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes, nor were they allowed to refer to themselves as Pequots. In the later 20th century, alleged Pequot descendants revived the tribe, achieving federal recognition and settlement of some land claims.

Some 500-1000 (scholars differ) women and children were shipped into slavery in Bermuda and Barbados.

The whole broader war that the colonists of Connecticut and Massachusetts waged against the Pequots ran from 1636 through 1638. This WP page on the war makes clear that the colonists, who were Puritans, attributed their victory in it to “an act of God”:

Let the whole Earth be filled with his glory! Thus the lord was pleased to smite our Enemies in the hinder Parts, and to give us their Land for an Inheritance.

Over the centuries, remnants of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation were able to regather. In 1983, they received formal recognition from the federal government of their status as a Tribal Nation– along with settlement of a longstanding land dispute. The MPTN’s website tells us this about the settlement:

It granted the Tribe federal recognition, enabling it to repurchase and place in trust the land covered in the Settlement Act. Currently, the reservation is 1,250 acres.

As the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation sought to settle its land claims, it also actively engaged in a number of economic enterprises, including the sale of cord wood, maple syrup, and garden vegetables, a swine project and the opening of a hydroponic greenhouse. Once the land claims were settled, the Tribe purchased and operated a restaurant, and established a sand and gravel business. In 1986, the Tribe opened its bingo operation, followed, in 1992, by the establishment of the first phase of Foxwoods Resort Casino.

The ceremonial groundbreaking for the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center took place on Oct. 20, 1993

Also, a statue of John Mason that was erected in 1889, triumphantly on the site of the former Pequot village, was removed from there due to popular protest in 1996 and taken to Windsor, CT; and according to this page on WP is “set to be removed” from there, as well.

Song Yingxing publishes his encyclopedia

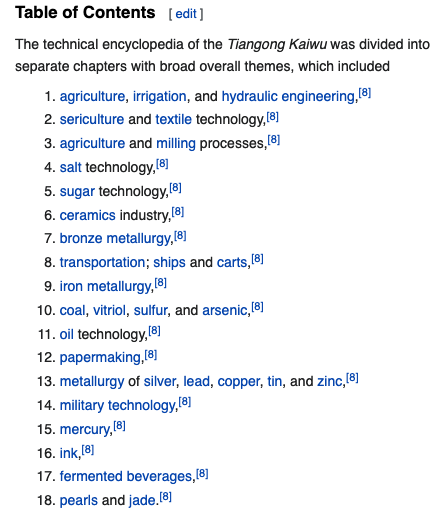

In May 1637, a Chinese polymath and minor official called Song Yingxing published an 87-page, woodblock-printed encyclopedia called the Tiangong Kaiwu (天工開物), or The Exploitation of the Works of Nature. He did so with funding privately provided by a patron, not by the (deeply withering) Ming rulers.

English-WP tells us:

It featured detailed illustrations that were valuable for historians in understanding many early Chinese production processes… As the historian Joseph Needham points out, the vast amount of accurately drawn illustrations in this encyclopedia dwarfed the amount provided in previous Chinese encyclopedias, making it a valuable written work in the history of Chinese literature. At the same time, the Tiangong Kaiwu broke from Chinese tradition by rarely referencing previous written work. It is instead written in a style strongly suggestive of first-hand experience. In the preface to the work, Song attributed this deviation from tradition to his poverty and low standing.

That WP page provides several examples of the contents of the encyclopedia. But it also notes this:

Copies of the book were very scarce in China during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) (due to the government’s establishment of monopolies over certain industries described in the book), but original copies of the book were preserved in Japan.

A fairly well-scanned version of the whole encyclopedia can be viewed or downloaded here.