In 1571 CE, by far the major development– from the perspective of “Western” Christian powers– was the Battle of Lepanto, in which an alliance of Christian navies dealt a big defeat to the Ottoman navy in the Mediterranean. Most of this post will be about that. Scroll on down.

But I also want to note that in May 1571 , a joint Crimean-Ottoman army (80,000 Crimean Tartars, 40,000 Ottomans, including irregulars) managed to travel up to the suburbs of Moscow. The fires they set there blew toward Moscow itself. English-WP tells us this about the 1571 Great Fire of Moscow:

People fled into stone churches to escape the flames, but the stone churches collapsed (either from the intensity of the fire or the pressure of the crowds.) People also jumped into the Moscow River to escape, where many drowned. The powder magazine of the Kremlin exploded and those hiding in the cellar there asphyxiated. The tsar ordered the dead found on the streets to be thrown into the river, which overflowed its banks and flooded parts of the town. Jerome Horsey wrote that it took more than a year to clear away all the bodies. It was one of the most severe fires in the history of the city. Historians estimate the number of casualties of the fire from 60,000 to as many over 200,000 people.

I’ll come back to further development in the Russian-Crimean War, next year.

The Battle of Lepanto

So last year, we left the Ottoman expeditionary force in Cyprus camped outside the besieged capital, Famagusta. This year, on August 1, they finally managed to take Famagusta from the city’s Venetian defenders and thus the whole of wealthy Cyprus fell under Ottoman control.

The Venetians had been running a robust and well-armed merchant empire in the East Mediterranean for a couple of centuries by then; and they did not have good relations with the Spanish regime, also like them Catholic, whose navy was powerful at the other end of the Med. (As for the French, as we know, during much of this period their navy was allied with the Ottoman navy.) So when the Venetians had started losing Cyprus in 1570, it took time for the pleas for help they sent to other Christian naval powers in the Med to have any effect. In the end, it was the Pope, Pius V, who managed to broker an alliance that involved naval units from the following powers:

- Spain (including the kingdoms of Naples, Sardinia, and Sicily)

- Venice

- Papal States (yes they had an army)

- Genoa

- Savoy

- Urbino

- Tuscany

- Malta

(Note: no France.)

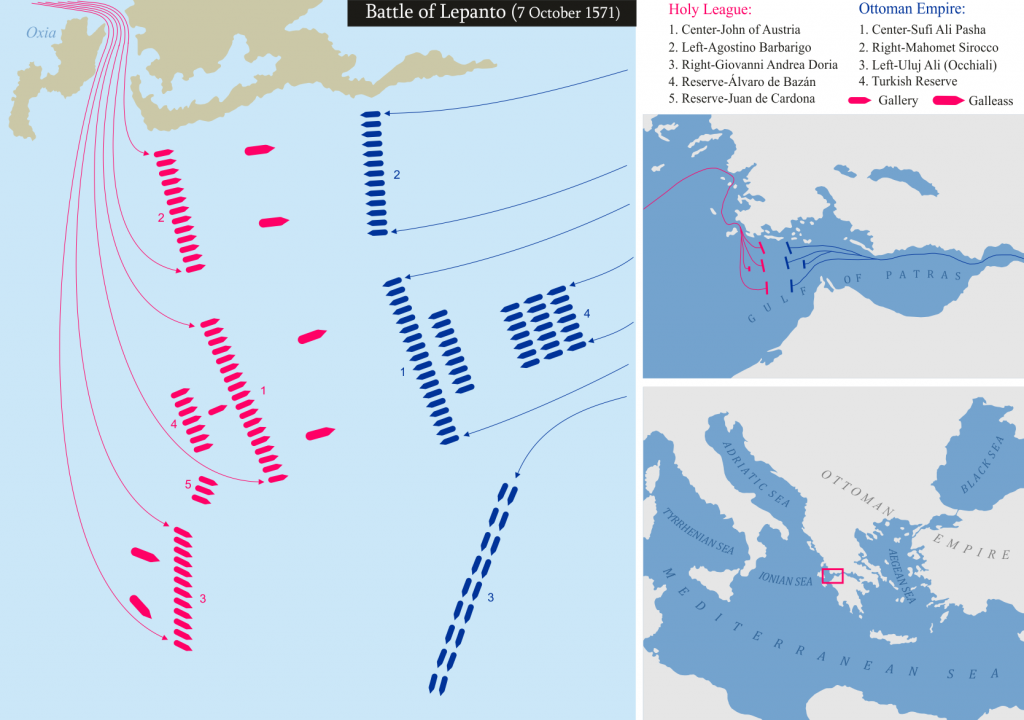

The Christian “Holy League” alliance had 60,000 men, of whom 20,000 were soldiers and 40,000 were sailors on a total of 212 ships. The Ottomans had 34,000 soldiers and 50,000 sailors on 278 ships. These ships were still overwhelmingly “galleys”, that is ships moved primarily by oars but with sails as supplements.

The Ottoman navy was lined up near Lepanto, in the Gulf of Patras off the west coast of today’s Greece; and the Christian navy assembled at Messina. English-WP tells us this:

An advantage for the Christians was the numerical superiority in guns and cannon aboard their ships, as well as the superior quality of the Spanish infantry. It is estimated that the Christians had 1,815 guns, while the Turks had only 750 with insufficient ammunition. The Christians embarked with their much improved arquebusier and musketeer forces, while the Ottomans trusted in their greatly feared composite bowmen.

The Christian fleet started from Messina on 16 September, crossing the Adriatic and creeping along the coast, arriving at the group of rocky islets lying just north of the opening of the Gulf of Corinth on 6 October. Serious conflict had broken out between Venetian and Spanish soldiers, and [Venetian commander Sebastiano] Venier enraged [Spanish and over-all commander Don Juan of Austria] by hanging a Spanish soldier for impudence. Despite bad weather, the Christian ships sailed south and, on 6 October, reached the port of Sami, Cephalonia (then also called Val d’Alessandria), where they remained for a while.

Early on 7 October, they sailed toward the Gulf of Patras, where they encountered the Ottoman fleet. While neither fleet had immediate strategic resources or objectives in the gulf, both chose to engage. The Ottoman fleet had an express order from the Sultan to fight, and John of Austria found it necessary to attack in order to maintain the integrity of the expedition in the face of personal and political disagreements within the Holy League.

On october 7, a Spanich lookout sighted the Ottoman fleet ahead. “Don Juan called a council of war and decided to offer battle. He travelled through his fleet in a swift sailing vessel, exhorting his officers and men to do their utmost. The Sacrament was administered to all, the galley slaves were freed from their chains (!), and the standard of the Holy League was raised to the truck of the flagship.”

Battle started soon after noon. Then this:

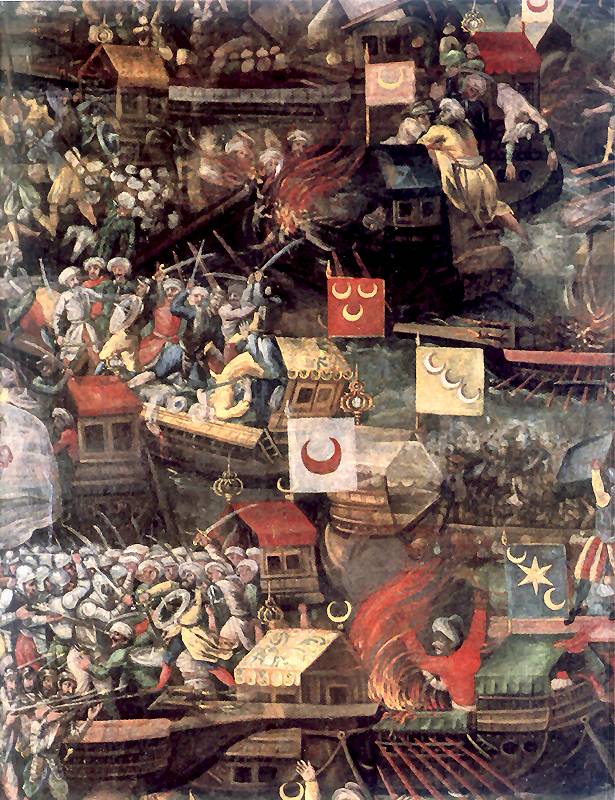

the centres clashed with such force that [Ottoman commander] Ali Pasha’s galley drove into the Real [the Spanish flagship] as far as the fourth rowing bench, and hand-to-hand fighting commenced around the two flagships, between the Spanish Tercio infantry and the Turkish janissaries. When the Real was nearly taken, Colonna came alongside, with the bow of his galley, and mounted a counter-attack. With the help of Colonna, the Turks were pushed off the Real and the Turkish flagship was boarded and swept. The entire crew of Ali Pasha’s flagship was killed, including Ali Pasha himself. The banner of the Holy League was hoisted on the captured ship, breaking the morale of the Turkish galleys nearby. After two hours of fighting, the Turks were beaten left and centre, although fighting continued for another two hours.

The right flank of the Christian side had a more complex time of it but by evening the fighting had ended, resulting in a very strong victory of the Christian side. “At the end of the battle, the Christians had taken 117 galleys and 20 galliots, and sunk or destroyed some 50 other ships. Around ten thousand Turks were taken prisoner, and many thousands of Christian slaves were rescued. The Christian side suffered around 7,500 deaths, the Turkish side about 30,000.”

The Turkish side also took some prisoners (though WP does not mention that.) Among them was Miguel Cervantes.

Throughout the centuries, the Battle of Lepanto has often been a crucial marker/symbol for the “Christian” right, identified as a prime example of how a militant Christian unity can defeat “the Turk” or whatever. In truth, though, the Holy League of 1571 did little or nothing to capitalize on its victory in that one big battle. The Ottomans got to keep Cyprus. English-WP says this:

while the Ottoman defeat has often been cited as the historical turning-point initiating the eventual stagnation of Ottoman territorial expansion, this was by no means an immediate consequence; even though the Christian victory at Lepanto confirmed the de facto division of the Mediterranean, with the eastern half under firm Ottoman control and the western under the Habsburgs and their Italian allies, halting the Ottoman encroachment on Italian territories, the Holy League did not regain any territories that had been lost to the Ottomans prior to Lepanto. Historian Paul K. Davis synopsizes the importance of Lepanto this way: “This Turkish defeat stopped Ottomans’ expansion into the Mediterranean, thus maintaining western dominance, and confidence grew in the west that Turks, previously unstoppable, could be beaten”

The Ottomans were quick to rebuild their navy. By 1572, about six months after the defeat, more than 150 galleys, 8 galleasses, and in total 250 ships had been built, including eight of the largest capital ships ever seen in the Mediterranean. With this new fleet the Ottoman Empire was able to reassert its supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean. Sultan Selim II’s Chief Minister, the Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu, even boasted to the Venetian emissary Marcantonio Barbaro that the Christian triumph at Lepanto caused no lasting harm to the Ottoman Empire, while the capture of Cyprus by the Ottomans in the same year was a significant blow, saying that: “You come to see how we bear our misfortune. But I would have you know the difference between your loss and ours. In wrestling Cyprus from you, we deprived you of an arm; in defeating our fleet, you have only shaved our beard. An arm when cut off cannot grow again; but a shorn beard will grow all the better for the razor.”

In 1572, the allied Christian fleet resumed operations and faced a renewed Ottoman navy of 200 vessels under Kılıç Ali Pasha, but the Ottoman commander actively avoided engaging the allied fleet and headed for the safety of the fortress of Modon. The arrival of the Spanish squadron of 55 ships evened the numbers on both sides and opened the opportunity for a decisive blow, but friction among the Christian leaders and the reluctance of Don Juan squandered the opportunity.

Pius V died on 1 May 1572. The diverging interests of the League members began to show, and the alliance began to unravel.