This is the 50th anniversary edition of the Project 500 Years daily bulletin. I have completed 10% of my self-assigned task! To mark the occasion I shall shortly– today or tomorrow– be issuing “Communique #2” for the project. But for now, this fascinating daily grind must continue. Readers: the main developments of 1570 CE:

- Ottoman navy takes Cyprus from Venice

- Spanish conquistadores seize Manila

- Intriguing Spanish-Jesuit foray to Virginia

- Ivan the Terrible’s crazed massacre at Novgorod

- Ortelius publishes world’s first World Atlas

Ottoman navy takes Cyprus from Venice

Since 1489, the large and wealthy island of Cyprus, with its ethnic-Greek population of around 160,000, had been under the rule of the wealthy merchant republic of Venice. English-WP tells us: “Aside from its location, which allowed the control of the Levantine trade, the island possessed a profitable production of cotton and sugar. To safeguard their most distant colony, the Venetians paid an annual tribute of 8,000 ducats to the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt, and after their conquest by the Ottomans in 1517, the agreement was renewed with the Ottoman Porte.”

But the new-ish Ottoman Sultan Selim II (“the Sot”)and his Grand Vizier wanted more. They wanted complete control of the island and it riches– and they were egged on in this ambition by an intriguing character called Joseph Nasi, a Portuguese Jew who had become the Sultan’s close friend, and who “harboured resentment towards Venice and hoped for his own nomination as King of Cyprus after its conquest—he already had a crown and a royal banner made to that effect.”

(Nasi is the first of two intriguing characters we’ll meet this year. One of his earlier schemes had been to resettle Jews in the towns of Tiberias and Safed in what was then part of Southern Syria. He started doing that in 1561, getting permission to do so from then-Sultan Suleiman, and took a few first steps. But when Selim decided to invade Cyprus, he abandoned his proto-Zionist project.)

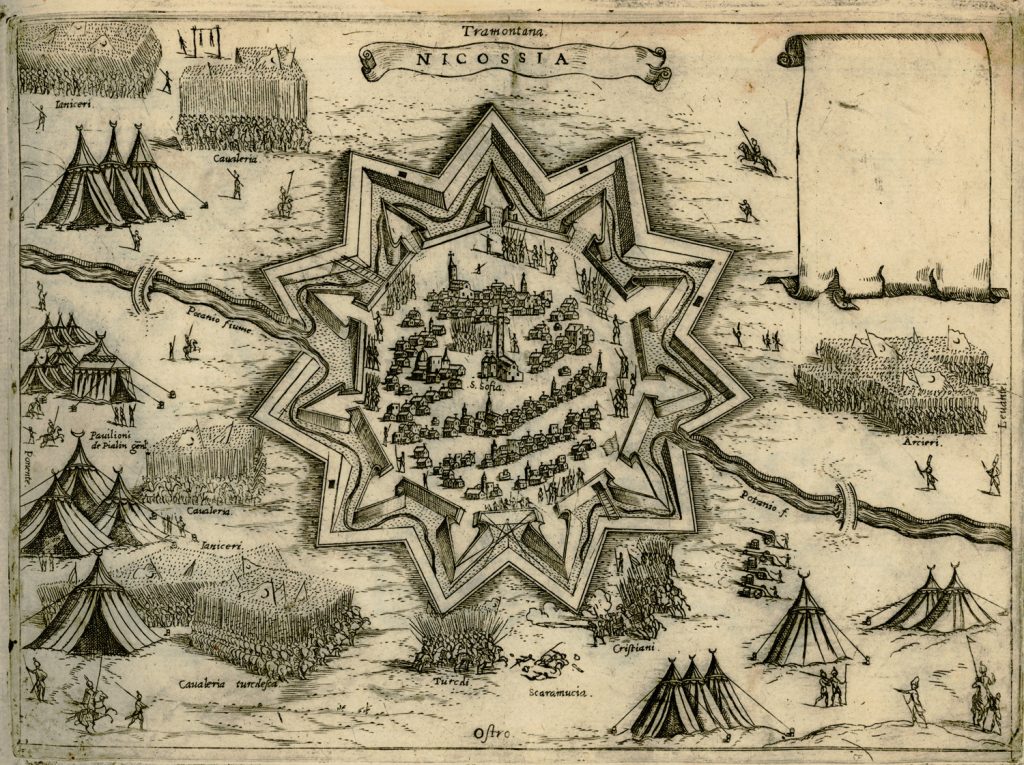

In late June 1570, the Ottoman invasion force of some 350–400 ships and 60,000–100,000 men, set sail for Cyprus. It landed unopposed at Salines, near Larnaca on the island’s southern shore on 3 July, and marched towards the capital, Nicosia, and after a short siege was able to capture it on September 9, massacring most of the city’s 20,000 inhabitants. The Ottomans were also meanwhile proceeding to the last Venetian stronghold at Famagusta where over the months that followed they dug “a huge network of criss-crossing trenches for a depth of three miles around the fortress… As the siege trenches neared the fortress and came within artillery range of the walls, ten forts of timber and packed earth and bales of cotton were erected.”

However, the Ottomans lacked the naval strength to completely blockade Famagusta from the sea as well, and the Venetians were able to resupply it and bring in reinforcements. So at the end of 1570, we’ll leave both parties dug in there so we can await the outcome in the years that follow…

Spanish conquistadores seize Manila

The conquistador who had established the first Spanish settlement in today’s Philippines (sailing over from today’s Mexico), Miguel López de Legazpi, had established it at Cebu. But he then found both Cebu and his next settlement attempt at Iloilo unworkable, because of insufficient food supplies and attacks by Portuguese pirates. English-WP tells us that, “He was in Cebu when he first heard about a well-supplied, fortified settlement to the north, and sent messages of friendship to its ruler, Rajah Matanda, whom he addressed as ‘King of Luzon.’ So he sent another conquistador, Martin de Goiti , to Manila and tasked him with negotiating the establishment of a Spanish fort there.”

Initial contacts with Matanda seemed promising but then another ruler, Rajah Sulayman, arrived and swore that the Tagalog people would never submit to Spanish rule. Then, this happened:

By May 24, negotiations had broken down, and according to the Spanish accounts, their ships fired their cannon as a signal for the expedition boats to return. Whether or not this claim was true, the rulers of Maynila perceived this to be an attack [!] and as a result, Sulayman ordered an attack on the Spanish forces still within the city. The battle was very brief. The Spanish Conquistadors together with their regiment of newly converted native warriors from the Visayas proved to be too overwhelming for the Tagalogs. The battle concluded with the settlement of Maynilad being set ablaze.

English-WP tells us that “A Kapampangan leader… later identified as Tarik Sulayman (from Arabic طارق سليمان Tāriq Sulaiman), refused to submit to the Spaniards and, after failing to gain the support of the kings of Manila (Lakandula, Matanda)… gathered a formidable force composed of Kapampangan warriors. He subsequently fought and lost the Battle of Bangkusay Channel. The Spanish solidified their control over Manila and Legazpi was able to establish a municipal government for Manila on June 24, 1571.”

Manila would later become the capital of the entire “Spanish East Indies” colony and subsequently the capital of the Philippines.

Intriguing Spanish-Jesuit foray to Virginia

The Spanish had succeeded in founding the first stable European-colonial settlement in the terrain of today’s United States– the one in “St. Augustine”, Florida– back in 1565. They later established small outposts along the east coast into Georgia and the Carolinas, some of them with Jesuit “missionaries” accompanying their military units. Along the way, in 1561, one of their expeditions had “kidnapped an Indian boy from the Chesapeake Bay region and took him to Mexico. The boy was instructed in the Catholic religion and baptized Don Luis.” They even took him, I suppose as some kind of native “trophy”, to Madrid where he had an audience with the King and received a thorough Jesuit education. Some Dominicans who were heading for Florida as missionaries took Don Luis with them, but they stopped off at Havana and abandoned their plans for Florida….

Meantime, the Jesuit “Vice Provincial of Havana”, Father Juan Bautista de Segura, decided he wanted to found a Jesuit mission on the Eastern Shore of today’s Virginia’s, at a place they called “Ajacán”– and to do so without having any protective military garrison.

WP: “His superiors expressed concerns but gave him permission to found what was to be called St. Mary’s Mission. He set out in August together with Father Luis de Quirós, former head of the Jesuit college among the Moors in Spain (!), six Jesuit brothers, and a Spanish boy named Alonso de Olmos, called Aloncito.”

“Don Luis” went with them to serve as their guide and interpreter.

More WP:

On September 10, the party landed in Ajacán on the north shore of one of the lower Chesapeake peninsulas. They constructed a small wooden hut with an adjoining room where Mass could be celebrated…

[Don Luis] soon left the Jesuits, settling with his own people at a distance of more than a day’s travel. When he failed to return, the Jesuits believed that he had abandoned them. They were frightened to be without anyone who knew the language… Around February 1571, three missionaries went toward the village where they thought that Don Luis was staying. Don Luis murdered them, then took other warriors to the main mission station where they killed the priests and the remaining six brothers, stealing their clothes and liturgical supplies. Only the young servant boy Alonso de Olmos was spared, and he was put under the care of a chief.

A Spanish supply ship went to the mission in 1572. Men came out in canoes dressed in clerical garb and tried to get them to land, then attacked. The Spaniards killed several, and captives told them about the young Spanish boy who survived. They exchanged some of their captives for Alonso, who told them about the massacre of the mission brothers.

In Augiust 1572, Florida’s Sanish governor arrived with an armed contingent to avenge the massacre of the Spanish and hoping to capture Don Luis. They never found him. But WP tells us that, the Spanish force, “baptized and hanged eight other Indians[and killed a total of 20 in their attack. The Spanish then abandoned plans for further activity in the region.”

That claim that the Florida conquistadores “baptized and hanged” some captives seemed poorly authenticated. But if true… O.M.G.

Anyway, this was all long before the English founded Jamestown.

Ivan the Terrible’s crazed massacre at Novgorod

Ivan’s expansions of his lands had generally been going pretty well for many years, but he was apparently becoming increasingly paranoid and deranged. He took it into his head that the Archbishop of the wealthy city of Novgorod and many of the city’s merchants were plotting to extricate themselves from his rule and ally instead with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Ivan’s shock troops were called the oprichniki. In late 1569 he deployed them to Novgorod; and in early January 1570 he joined them there, accompanied by his son, his court, and 1,500 musketeers. There were terrible massacres, and Novgorod never recovered.

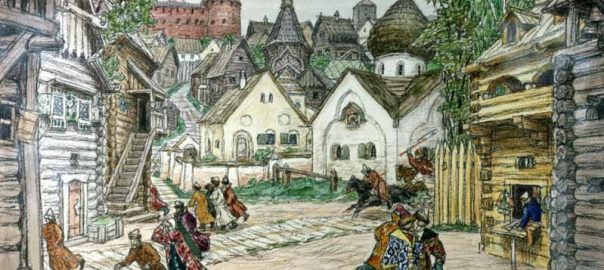

(The banner image is Apollinary Vasnetsov’s 1911 painting of people fleeing Ivan’s oprichniki.)

Ortelius publishes world’s first World Atlas

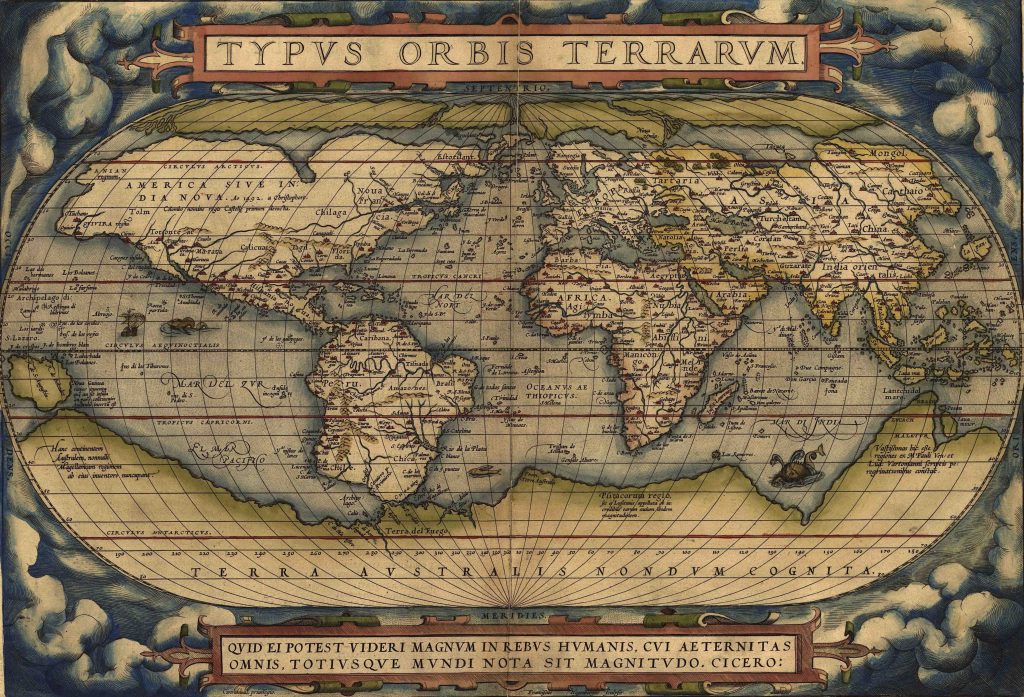

In 1569, Mercator had published his first multi-sheet map of the world using his own, innovative means of projection. Now, just a year later, his fellow Nederlander Abraham Ortelius would publish a first, bound world atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. It contained virtually no maps he had made himself, but contained 53 maps drawn and engraved by other masters in his native Antwerp, to whose work he gave due attribution.

English-WP tells us:

The moneyed middle class, which had much interest in knowledge and science, turned out to be very much interested in the convenient size and the pooling of knowledge. For buyers who were not strong in Latin, from the end of 1572, in addition to the Latin version, Dutch, German and French editions were published. This rapid success prompted the Ortelius Theatrum to constantly expand and improve. In 1573, he released 17 more additional maps under the title Additamentum Theatri Orbis Terrarum, bringing the total at 70 maps. By Ortelius’ death in 1598, there were twenty-five editions that had appeared in seven different languages.

You could perhaps describe it as a kind of geographic Wikipedia of its day– at a time when geographic knowledge was very highly valued.

Plus, by the way, Ortelius was the first person who proposed the theory of continental drift. According to U.S. geographer W. J. Kious, in the work Thesaurus Geographicus Ortelius, “suggested that the Americas were ‘torn away from Europe and Africa … by earthquakes and floods’ and went on to say: ‘The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three [continents]’.”