These were the main developments in 1539 CE that impacted the development of the “West”‘s domination of world affairs:

- In January, the Catholic kings of Spain and France set aside the rivalry they had pursued for many years to reach agreement that neither would make further alliances with England, where King Henry VIII had now very definitively split with Catholicism. The French king continued with building his state administration.

- Protestantism continued to make new inroads in Europe (not solely in England.) In Iceland, Lutheranism was “forcibly introduced” despite the opposition of a local bishop.

- In Ming China, Henan province was visited by swarms of locusts and a major epidemic of the plague.

- In Pavia in the north of today’s Italy, Teseo Ambrogio published a print volume that presented 13 Middle Eastern languages and their ancient liturgical alphabets to the Latin-reading public in Europe. The production of empire-useful knowledge continued apace.

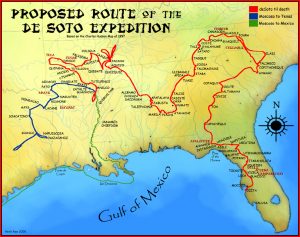

- Empire-building-wise, the main developments of the year were the exploits of Spanish conquistador Hernando De Soto. He had a fascinating history, emblematic of the lives of many of the “White”-supremacist, testosterone-driven adventurers who had driven both the Christian Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula and, later, the conquistadores‘ plundering in the Americas. Born in 1495 to a family of minor nobility of modest means De Soto traveled with an expedition to Columbia in 1514, participating in various conquistador raids around Central America till he struck it very rich by being awarded an encomienda in Nicaragua in 1524. (That was essentially the award of a parcel of land and free rein to enslave, exploit, and use all the natural and human resources within it for his own benefit.) English-WP says: “Brave leadership, unwavering loyalty, and ruthless schemes for the extortion of native villages for their captured chiefs became de Soto’s hallmarks during the conquest of Central America.” After Nicaragua, he set off for further plundering adventure by joining Pizarro’s conquest of Peru. He made a large fortune from the plunder of Cusco; then in 1536 he returned to Spain where he was awarded a prestigious order of nobility, the governorship of Cuba, and “the right to conquer Florida.” Per English-WP, he “was expected to colonize the North American continent for Spain within 4 years, for which his family would be given a sizable piece of land.” Long story short, in 1539 he set out for Florida and spent about three years leading his followers around the southeast of today’s United States before dying of fever in 1542, in either present-day Louisiana or Arkansas.

The view that (Anglo and Hispanic) U.S. Americans hold of De Soto seems to have changed significantly over time. Of course, the arrival of Anglo settlers to the current United States would not even start to happen until many decades after De Soto’s travels, and even after Anglos settled along the eastern seaboard, Spain (later joined by France) continued to control most of the areas in which De Soto had traveled, and then right across the continent to California…

In the Hispanic world, De Soto may have continued to be viewed as a heroic explorer for many years after his death–though in itself, that had been a pretty ignominious moment for him and for the large marauding band of “explorers” that he led. Also, per WP, the Spanish monarch was kind of disappointed that De Soto discovered nothing in Florida etc that came close to comparing with the massive riches he and his compadres had discovered (and looted) in Peru.

But there was a whole period in “Anglo” history in the USA when De Soto was also lionized as a great “White” explorer. For example, in 1853 CE, one of the 18 ft x 12 ft paintings commissioned to adorn the Capitol Rotunda, was a painting of his “discovery” of the Mississippi.

And right through until recently (and maybe even now), various small communities in the southeastern USA compete for recognition as being places associated with his expedition.

The banner image at the top here is a representation of the burial (in the Mississippi) of De Soto, that was used to illustrate an 1876 U.S. textbook “Pioneers in the settlement of America.”

The English-WP page on De Soto provides numerous vignettes regarding his exploits in his 1539-42 expedition. They include this one from 1540:

de Soto was led into Mauvila (or Mabila), a fortified city in southern Alabama.[37] The Mobilian tribe, under chief Tuskaloosa, ambushed de Soto’s army.[37] Other sources suggest de Soto’s men were attacked after attempting to force their way into a cabin occupied by Tuskaloosa.[38] The Spaniards fought their way out, and retaliated by burning the town to the ground. During the nine-hour encounter, about 200 Spaniards died, and 150 more were badly wounded, according to the chronicler Elvas.[39] Twenty more died during the next few weeks. They killed an estimated 2,000-6,000 warriors at Mabila, making the battle one of the bloodiest in recorded North American history.[40]

English-WP currently has this summation of the effects of De Soto’s expedition:

De Soto was instrumental in contributing to the development of a hostile relationship between many Native American tribes and Europeans. When his expedition encountered hostile natives in the new lands, more often than not it was his men who instigated the clashes.

More devastating than the battles were the chronic diseases carried by the members of the expedition. Because the indigenous people lacked the immunity which the Europeans had acquired through generations of exposure to these Eurasian diseases, the Native Americans suffered epidemics of illness after exposure to such diseases as measles, smallpox, and chicken pox. Several areas traversed by the expedition became depopulated by disease caused by contact with the Europeans. Seeing the high fatalities and devastation caused, many natives fled the populated areas for the surrounding hills and swamps. In some areas, the social structure changed because of high population losses due to epidemics.[58]

The records of the expedition contributed greatly to European knowledge about the geography, biology, and ethnology of the New World…

Of course, these latter kinds of knowledge speedily all became used to continue and intensify the process of European colonial plunder of this portion of the Americas.