A few weeks ago, my colleague on the board of Just World Educational Richard Falk and I launched a new initiative, an exploration of the ways the current “Covid era” has been upending the global balance balance. You can read more about our “World After Covid” project, here.

It’s been intellectually engaging to get this project up and running. I launched it by planning a series of weekly, one-on-one webinars featuring guests with a diversity of life experiences and perspectives, held every Wednesday at 1 pm ET. Richard was the first guest; then last week, we had Medea Benjamin, co-founder of CODEPINK. Tomorrow, we’ll have the veteran African-American labor+rights activist and thinker Bill Fletcher, Jr. And next week, Vijay Prashad, head of the Tricontinental Institute.

(By the way, if you missed our first two sessions, you can catch the videos of them here for Falk, and here for Medea.)

This project is, I’ll confess, starting to take over my life a bit. But it’s also been really interesting for me to get to know these amazing people who are my guests a little better, and to really engage with their views on this very momentous topic.

So now, I’m really looking forward to tomorrow’s session, with Bill Fletcher. We’ll be discussing a variety of topics, including:

- The #BlackLivesMatter movement and its significant worldwide resonance;

- Lessons the pro-justice and anti-hegemony movement in this country can learn from the collapse of both Portuguese colonialism in Southern Africa and the White settler-colonial Apartheid regime there; and

- Broader perspectives on the current shifts in the global balance, including the risks of entrenched powers here in the united States ginning up a “Cold War”– or God forbid even a “Hot War”, with China.

If you’re reading this blog post before 1pm ET on June 24, be sure to pre-register for the webinar on Zoom, which you can do here. (Or, you can catch it “live”on JWE’s Facebook page.)

Anyway, one of the things I found when I was preparing for tomorrow’s session was this blog post, “Rediscovering ‘The Souls of White Folk'”, that Bill Fletcher wrote back in November 2010.

He wrote:

“The Souls of White Folk” was an essay written in the aftermath of World War I and the despicable Versailles Treaty of 1919 which formally ended the war. Mainstream historians often focus on the mean-spirited punishment that the Allied Powers brought upon Germany, thereby laying the foundation for World War II. Little attention is given, however, to the hypocritical attitude of the Allied Powers with respect to the colonial world, the “darker races,” to borrow from the title of Vijay Prashad’s excellent book.

Representatives of the colonial world (including from Black America) gathered in Versailles to ascertain whether the Allied Powers (USA, Britain, France, Italy) would be true to their commitment to support the right of national self-determination. The future leader of the Vietnamese Revolution, Ho Chi Minh, was one such person who made the trek to Versailles, hoping that Vietnam, and the rest of Indochina, would secure self-determination.

Instead of receiving justice, the colored peoples of the world were ignored. The former colonies of Germany were either handed over outright to other colonial powers or they were placed into a League of Nations trusteeship, but in neither case were they able to secure independence…

Now, because of my background as a Middle East specialist, I’d focused a lot on the terrible role the Versailles Conference played in denying self-determination to the Arab peoples… but I hadn’t paid enough attention to the role it played in denying self-determination to nations of the “Global South”– the ‘darker nations”– more generally.

Fletcher wrote:

“The Souls of White Folk” would be a powerful document if it simply stopped there, but Dubois goes further and in doing so makes this document one that cannot be read simply as an historical piece, but one that remains critically important today.

Dubois turns to the question of race and, in fact, white privilege, and demonstrates the linkages between race and imperialism. Dubois notes, for example: “Behold little Belgium and her pitiable plight, but has the world forgotten Congo?”

For those not up on their World War I history (and no criticism is implied), much was made of the German subjugation of Belgium. Yet Dubois asks about the Congo, and this is not simply a throw-away line. Belgium, through King Leopold, controlled the Congo during which time it put to death 10 to 12 million people.

Dubois, of course, could not know what was soon to be facing European Jews and the annihilation of 6 million of them at the hands of the Nazis (who in 1920 were just getting organized), but that Holocaust received international attention, whereas the holocaust inflicted on the Congolese people was all but ignored at the time that it happened, in the aftermath of World War I, and, indeed, in the aftermath of World War II. For Dubois, imperialism was not racially blind.

Dubois situates the matter of race directly with modern imperialism. He makes the point that the degrading of this or that part of humanity has been with us for thousands of years, but that it is with the rise of modern Europe that we see the rise of what he terms “the eternal world-wide mark of meanness,–color!”

Well, upon reading Bill’s intriguing essay, I had to go back and read Dubois’s whole essay… which luckily was posted in full on Medium (by Malory Nye) in 2016: here.

It’s good to realize that Dubois almost certainly chose the title for his essay to serve as a counterpoint to the title of his seminal 1903 essay collection “The Souls of Black Folk.” Thus, in his 1920 essay, he was not only writing about the role that “White” privilege already firmly held in the organization/domination of the world. He was also (as Bill Fletcher noted) exploring the extreme distortion in the souls of white folk that had already, back in 1920, led them to maintain that globe-girdling system of “White” European racial domination for– in many cases, including here in the Americas– several centuries by then.

It’s good to realize that Dubois almost certainly chose the title for his essay to serve as a counterpoint to the title of his seminal 1903 essay collection “The Souls of Black Folk.” Thus, in his 1920 essay, he was not only writing about the role that “White” privilege already firmly held in the organization/domination of the world. He was also (as Bill Fletcher noted) exploring the extreme distortion in the souls of white folk that had already, back in 1920, led them to maintain that globe-girdling system of “White” European racial domination for– in many cases, including here in the Americas– several centuries by then.

And here we are, a further 100 years later, and we still live in a world in which the United States and its “White” European NATO allies are still hanging on to their domination of the world. (Though this domination position is now, I believe, eroding or collapsing somewhat rapidly.)

I find it extremely depressing to recall how long “White” hegemony, and its corollary here in the United States and worldwide, “White” privilege, have been allowed to continue. But now– please God!– we have a chance to change this, and to rebuild a world in which every human person is valued, nurtured, and celebrated.

Bill Fletcher has been working to build such a world for many decades. I am really looking forward to your conversation tomorrow!

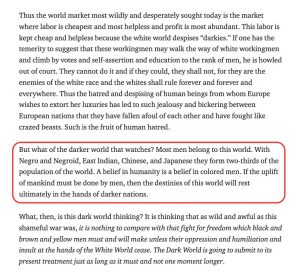

Here, meanwhile, is another excerpt from “The Souls of White Folk” (though you should absolutely head over to the text and read the whole thing):