Yesterday, the OECD dropped its twice-yearly projection of the economic performances for 2020 of its 36 pro-American and mainly capitalist members– as well as those of other major actors in the world economy, including China and Russia. It makes understandably depressing reading. The OECD’s economists worked their forecasts according to two different types of incidence of Covid-19: either a “single strike”, whose effects would last at least two years, or a W-shaped “double strike”, whose effects would last more than two years. (Remember, though, the San Francisco Fed’s recent historical report– PDF here— that found that the bad economic effects of pandemics last at least 40 years… )

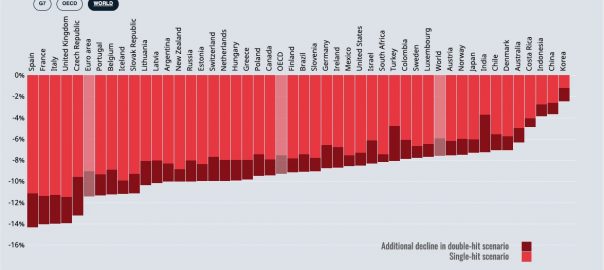

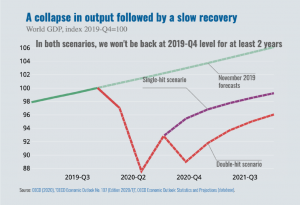

Here at right is what the OECD forecast– for the whole world’s GDP. The single-hit scenario is the purple branch, and the red is the double-hit. The details of what they projected for total GDP decreases for 2020, for each of the world’s significant countries, is as shown in the graph at the head of this blog post– again, with two levels indicated for each country: the light red bar shows the expected GDP decrease if Covid-19 inflicts only a “single” hit, while the dark red shows the addendum if there’s a double hit…

Here at right is what the OECD forecast– for the whole world’s GDP. The single-hit scenario is the purple branch, and the red is the double-hit. The details of what they projected for total GDP decreases for 2020, for each of the world’s significant countries, is as shown in the graph at the head of this blog post– again, with two levels indicated for each country: the light red bar shows the expected GDP decrease if Covid-19 inflicts only a “single” hit, while the dark red shows the addendum if there’s a double hit…

I have a problem with the OECD’s methodology here on a number of levels. First, their concept of a relatively “clean” double hit seems misleading. I realize that many infectious disease specialists believe there’s a noticeably increased risk of spread of Covid when the weather gets colder. (In which case, we should probably be seeing some of that effect in Southern-Hemisphere countries right now? I am not sure whether there’s any evidence on that yet?) But anyway, most of the world’s big economies are in the Northern Hemisphere, so the OECD’s fear of a “double hit” is centered around a recurrence of spread starting in 2020-Q3 and showing its main impact on the economy in 2020-Q4; but then, the economy bounces back pretty cleanly from 2020-Q4 on.

Really?

My strong sense of the spread of this virus and its economic effects is much murkier and more nuanced than that.

My strong sense of the spread of this virus and its economic effects is much murkier and more nuanced than that.

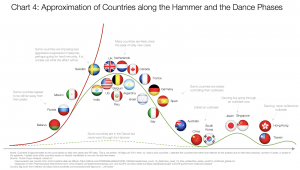

Regarding virus spread, it’s worth going back to this excellent April 20 Medium post in which Tomas Pueyo was spelling out his “hammer and dance” theory– and showing (in this graphic here) where he saw various countries as lying, at that point, on his “hammer and dance” curve.

One of the key things Pueyo was showing is that there is no simple, straightforward “W” for infection rates. The “dance” part of the virus’s spread can bounce up and down any number of times until we have — hopefully soon– full access to an effective vaccine.

That has a number of consequences. It means the economic effects also won’t display any kind of a clean “W”. Indeed, because of the general uncertainty over the virus’s behavior and effects, many people are already showing themselves reluctant to simply go back to work even after their governments assure them they can and should do so.

Plus, the ways that people will work will have to change, in many ways. It’s not just meatpackers having to put up plastic shields between their work-stations. It’s office-workers having to either stagger their arrival in transit trains and buses, and their use of elevators in buildings. It’s business people and leisure travelers being afraid to travel in airplanes… Many, many actions that have been drivers of “normal” economic activity in capitalist countries until now will be sharply reduced, changed drastically, or ended.

Just check out some of these graphs from the “Calculated Risk” blog.

The combination of the effects of lockdowns and the totally natural desire of actual people to minimize their exposure to Covid-related risks means that badly Covid-affected countries like the United States and almost all the other advanced capitalist countries (with some key exceptions) could well remain mired in Covid-sparked recessions for as long as it takes to find and distribute an effective vaccine.

The effect of this virus has already been like a gruesome case of musical chairs in which, in around mid-March, the music stopped and we all rushed for our chairs. But when will the music actually start again? For most of us living in capitalist countries, not until we have a vaccine, I think.