The biggest news of 1695 CE was the capture by a small English pirate flotilla in the Bab al-Mandeb strait of a heavily laden Mughal treasure ship returning to Surat from the Hajj. This event, which seems to have been very well documented from several points of view, including a fairly authoritative Indian one, illustrates numerous facets of the role that piratic looting played in the building of England’s global raiding/trading empire. Today’s post will mainly explore this pirate raid, which was led by a mariner called variously Henry Every, Henry Avery, Jack Avery, John Avery, Benjamin Bridgeman, or Long Ben.

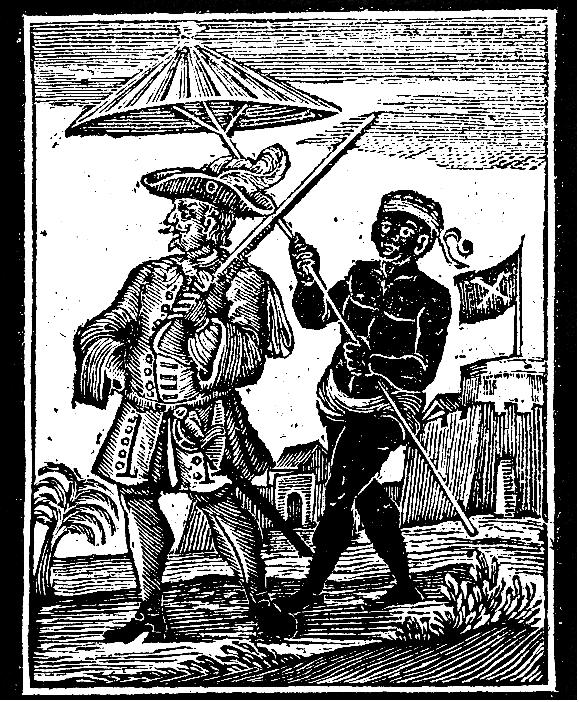

(The banner image above is a depiction of “Jack Avery” plundering the “Great Mogul” on an early 20th-century British, or American, cigarette card.)

Of course, during 1695, the “Nine Years War” that pitted France against all the other European imperial powers combined, also continued, on the continent of Europe, in the seas skirting it, and in distant regions like the Caribbean where France and several of its European opponents continued to vie for imperial influence…

One other noteworthy event that occurred in 1695 was that in February, amidst a series of Ottoman losses to the Habsburgs in Hungary, the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed II died. He was immediately succeeded by the 31-year-old Ottoman prince who became Mustafa II. It’s not clear to me whether Mustafa had, like most other Ottoman princes, had to spend most of his life until that point locked up in the “prince-cage” in Topkapi Palace. But it is pretty certain that, in the absence of any clear rules of primogeniture in the Ottoman dynasty, the succession was almost completely orchestrated by the very powerful coterie of officials under the Grand Vizier. By this point, the Ottoman princes (and the sultans that a few of them became) served more as thoroughbred, Ottoman-descended pets for the Grand Viziers than as actual rulers. Mustafa II, however, did have his portrait painted in full armor and was reported to have “led” a couple of military campaigns…

But meanwhile, back in Pirate-land (aka England)…

Career of pirate Henry Every reveals a lot about the roots of England’s empire

Every seems to have been born in 1659 in southwest England, home-region of Francis Drake and many famous English pirates. He joined the Royal Navy while still quite young, and may have served in various of its campaigns– bombarding Algiers, buccaneering in the Caribbean, the capture of a French convoy off the coast of Brest, the Battle of Beachy Head, and so on.

Englisgh-Wikipedia continues his biography thus:

After discharge from the Royal Navy, Every entered the Atlantic slave trade. Between 1660 and 1698, the Royal African Company (RAC) maintained a monopoly over all English slave trade, making it illegal to sell slaves without a license. To ensure compliance, the navy protected the company’s interests along the West African coast. Although illegal, unlicensed slaving could be a highly lucrative enterprise, as Every was certainly aware; the prospect of profits ensured that violations of the company’s monopoly by “interlopers” (unlicensed slavers) remained a fairly common crime.

In 1693, Every is identified in a journal prepared by an agent of the RAC, Captain Thomas Phillips of Hannibal, then on a slaving mission on the Guinea coast, who writes: “I have no where upon the coast met the negroes so shy as here, which makes me fancy they have had tricks play’d them by such blades as Long Ben, alias Every, who have seiz’d them and carry’d them away.”… Captain Phillips, who according to his own writings had come across Every on more than one occasion—and may have even known him personally—also alluded to Every as slave trading under a commission from Issac Richier, the unpopular Bermudian governor who was later removed from his post for his carousing behavior. However, Every’s slave trading employment is relatively undocumented.

WP tells us that in 1693 this happened:

In the spring of 1693, several London-based investors led by Sir James Houblon, a wealthy merchant hoping to reinvigorate the stagnating English economy, assembled an ambitious venture known as the Spanish Expedition Shipping. The venture consisted of four warships [one of them named Charles II]… Under a trading and salvage license from the Spanish, the venture’s mission was to sail to the Spanish West Indies, where the convoy would conduct trade, supply the Spanish with arms, and recover treasure from wrecked galleons while plundering the French possessions in the area.

So yes, that was basically one of the key ways these European nations would wage war against each other around the world: by plundering each other’s colonial “possessions”. Noteworthy here, too, is the fact that James Houblon, listed as the principal financier of the planned anti-French plundering expedition, was not just any old investor. According to his page on WP, he was,

an influential merchant and Member of Parliament for the City of London…. [who] invested heavily in the East India and Iberian trades, specialising in the import of Port wine. He held appointments in the East India Company and the Levant Company. With his younger brother John, he was instrumental in establishing the Bank of England and was a director from the founding of the bank in 1692. He was elected an Alderman of the City of London in 1692, and was knighted shortly afterwards…

So before the “Spanish Expedition” could go to the West Indies to start their plundering, they needed to go to Spain to get the “letters of marque” from the Spanish authorities that would make their venture legitimate in Spanish eyes. (Why didn’t they try to get “letters of marque” from London? They probably thought the Spanish version would give them more protection in the parts of the Caribbean they were heading for…)

They sailed first to Corunna in northern Spain, where there was some problem getting the letters of marque. As the wait dragged on into several months, the leaders of the expedition got into big fights with the sailors, who wanted to get paid. Henry Every was the first mate on one of these ships… Every emerged as a leader of the rebellious sailors, and in May 1694 they mutinied against their captains. WP tells us this:

Every was easily able to convince the men to sail to the Indian Ocean as pirates, since their original mission had greatly resembled piracy and Every was renowned for his powers of persuasion. He may have mentioned Thomas Tew’s success capturing an enormous prize in the Red Sea only a year earlier. The crew quickly settled the subject of payment by deciding that each member would get one share of the treasure, and the captain would get two. Every then renamed Charles II the Fancy… and set a course for the Cape of Good Hope.

Near Cape Verde, the pirate flotilla committed their first act of piracy:

robbing three English merchantmen from Barbados of provisions and supplies. Nine of the men from these ships were quickly persuaded to join Every’s crew, who now numbered about ninety-four men. Every then sailed to the Guinea coast, where he tricked a local chieftain into boarding Fancy under the false pretense of trade, and forcibly took his and his men’s wealth, leaving them slaves… In October 1694, Fancy captured two Danish privateers near the island of Príncipe, stripping the ships of ivory and gold and welcoming approximately seventeen defecting Danes aboard.

He stopped to do a resupply in Madagascar and again in the Comoros: “Here Every’s crew rested and took on provisions, later capturing a passing French pirate ship, looting the vessel and recruiting some forty of the crew to join their own company. Every’s total strength was now about 150 men.”

In 1695, he sailed up to the small volcanic island of Perim, at the mouth of the Bab el-Mandeb strait, which he reached in August. There, he teamed up with five other English prate captains to await the arrival of the Indian treasure fleet– of whose itinerary, he had apparently learned somewhere along the way. WP tells us this:

All of these captains were carrying privateering commissions that implicated almost the entire Eastern Seaboard of North America. [That is, they must have had letters of marque from various colonies in North America that gave them ‘license’ to attack and plunder enemy shipping.] Every was elected admiral of the new six-ship pirate flotilla… and now found himself in command of over 440 men while they lay in wait for the Indian fleet. A convoy of twenty-five Grand Mughal ships, including the enormous 1,600-ton Ganj-i-sawai with eighty cannons, and its escort, the 600-ton Fateh Muhammed, were spotted passing the straits en route to Surat [that is, heading south.] Although the convoy had managed to elude the pirate fleet during the night, the pirates gave chase…

The pirates caught up with Fateh Muhammed four or five days later. Perhaps intimidated by Fancy‘s forty-six guns or weakened by an earlier battle… Fateh Muhammed‘s crew put up little resistance; Every’s pirates then sacked the ship, which had belonged to one Abdul Ghaffar, reportedly Surat’s wealthiest merchant. While Fateh Muhammed‘s treasure of some £50,000 to £60,000 was enough to buy Fancy fifty times over, once the treasure was shared out among the pirate fleet, Every’s crew received only small shares…

Ganj-i-sawai, captained by one Muhammad Ibrahim, was a fearsome opponent, mounting eighty guns and a musket-armed guard of four hundred, as well as six hundred other passengers. But the opening volley evened the odds, as Every’s lucky broadside shot his enemy’s mainmast by the board. With Ganj-i-sawai unable to escape, Fancy drew alongside. For a moment, a volley of Indian musket fire prevented the pirates from clambering aboard, but one of Ganj-i-sawai‘s powerful cannons exploded, instantly killing many and demoralizing the Indian crew, who ran below deck or fought to put out the spreading fires. Every’s men took advantage of the confusion, quickly scaling Ganj-i-sawai‘s steep sides. The crew of Pearl, initially fearful of attacking Ganj-i-sawai, now took heart and joined Every’s crew on Indian ship’s deck. A ferocious hand-to-hand battle then ensued, lasting two to three hours.

Muhammad Hashim Khafi Khan, a contemporary Indian historian who was in Surat at the time, wrote that, as Every’s men boarded the ship, Ganj-i-sawai‘s captain ran below decks where he armed the slave girls and sent them up to fight the pirates. Khafi Khan’s account of the battle, appearing in his multivolume work The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians, places blame squarely on Captain Ibrahim for the failure, writing: “The Christians are not bold in the use of the sword, and there were so many weapons on board the royal vessel that if the captain had made any resistance, they must have been defeated.” In any case, after several hours of stubborn but leaderless resistance, the ship surrendered. In his defense, Captain Ibrahim would later report that “many of the enemy were sent to hell.” Indeed, Every’s outnumbered crew may have suffered anywhere from several to over a hundred casualties, although these figures are uncertain.

According to Khafi Khan, the victorious pirates subjected their captives to an orgy of horror that lasted several days, raping and killing their terrified prisoners deck by deck. The pirates reportedly utilized torture to extract information from their prisoners, who had hidden the treasure in the ship’s holds. Some of the Muslim women apparently committed suicide to avoid violation, while those women who did not kill themselves or die from the pirates’ brutality were taken aboard Fancy.

Although stories of brutality by the pirates have been dismissed by sympathizers as sensationalism, they are corroborated by the depositions Every’s men provided following their capture. John Sparkes testified in his “Last Dying Words and Confession” that the “inhuman treatment and merciless tortures inflicted on the poor Indians and their women still affected his soul,” and that, while apparently unremorseful for his acts of piracy, which were of “lesser concern,” he was nevertheless repentant for the “horrid barbarities he had committed, though only on the bodies of the heathen.” Philip Middleton testified that several of the Indian men were murdered, while they also “put several to the torture” and Every’s men “lay with the women aboard, and there were several that, from their jewels and habits, seemed to be of better quality than the rest.” Furthermore, on 12 October 1695, Sir John Gayer, then-governor of Bombay and president of the EIC, sent a letter to the Lords of Trade, writing:

“It is certain the Pyrates, which these People affirm were all English, did do very barbarously by the People of the Ganj-i-sawai and Abdul Gofor’s Ship, to make them confess where their Money was, and there happened to be a great Umbraws Wife (as Wee hear) related to the King, returning from her Pilgrimage to Mecha, in her old age. She they abused very much, and forced severall other Women, which Caused one person of Quality, his Wife and Nurse, to kill themselves to prevent the Husbands seing them (and their being) ravished.”

… At any rate, the survivors were left aboard their emptied ships, which the pirates set free to continue on their voyage back to India. The loot from Ganj-i-sawai, the greatest ship in the Muslim fleet, totaled somewhere between £200,000 and £600,000, including 500,000 gold and silver pieces. All told, it may have been the richest ship ever taken by pirates (see Career wealth below).

The pirate ships then split up, having also split up the loot among them. Doubtless, Every took the largest portion. He took the Fancy first of all to “Bourbon” (Réunion), which lies a little east of Madagascar, and arrived there in November 1695:

Here the crew shared out £1,000 (roughly £93,300 to £128,000 today) per man, more money than most sailors made in their lifetime. On top of this, each man received an additional share of gemstones. As Every had promised, his men now found themselves glutted with “gold enough to dazzle the eyes.” However, this enormous victory had essentially made Every and his crew marked men, and there was a great deal of dispute among the crew about the best place to sail. The French and Danes decided to leave Every’s crew, preferring to stay in Bourbon. The remaining men set course, after some dissension, for Nassau in the Bahamas, Every purchasing some ninety slaves shortly before sailing. Along the way, the slaves would be used for the ship’s most difficult labor and, being “the most consistent item of trade,” could later be traded for whatever the pirates wanted. In this way, Every’s men avoided using their foreign currency, which might reveal their identities.

They arrived in the Bahamas in spring 1696. Lying at anchor a little off the capital, Nassau, he sent a letter to,

the island’s governor, Sir Nicholas Trott. The letter explained that Fancy had just returned from the coast of Africa, and the ship’s crew of 113 self-identified interlopers [English slave-traders operating east of the Cape of Good Hope without the permission of the EIC] now needed some shore time. In return for letting Fancy enter the harbor and for keeping the men’s violation of the EIC’s trading monopoly a secret, the crew would pay Trott a combined total of £860. Their captain, a man named “Henry Bridgeman,” also promised the ship to the governor as a gift once his crew unloaded the cargo.

For Trott, this proved a tempting offer. The Nine Years’ War had been raging for eight years, and the island, which the Royal Navy had not visited in several years, was perilously underpopulated. Trott knew that the French had recently captured Exuma, 140 miles (230 km) to the southeast, and were now headed for New Providence. With only sixty or seventy men living in the town [Nassau], half of whom served guard duty at any one time, there was no practical way to keep Nassau’s twenty-eight cannons fully manned. However, if Fancy‘s crew stayed in Nassau it would more than double the island’s male population, while the very presence of the heavily-armed ship in the harbor might deter a French attack. On the other hand, turning away “Bridgeman” might spell disaster if his intentions turned violent, as his crew of 113 (plus ninety slaves) would easily defeat the island’s inhabitants. Lastly, there was also the bribe to consider, which was three times Trott’s annual salary of £300.

Trott called a meeting of Nassau’s governing council… The council agreed to allow Fancy to enter the harbor, apparently having never been told of the private bribe. Trott sent a letter to Every instructing him that his crew “were welcome to come and to go as they pleased.” Soon after, Trott met Every personally on land in what must have been a closed-door meeting. Fancy was then handed over to the governor, who found that extra bribes—fifty tons of ivory tusks, one hundred barrels of gunpowder, several chests of firearms and ammunition, and an assortment of ship anchors—had been left in the hold for him.

The wealth of foreign-minted coins could not have escaped Trott. He must have known that the ship’s crew were not merely unlicensed slavers, likely noting the patched-up battle damage on Fancy. When word eventually reached him that the Royal Navy and the EIC were hunting for Fancy and that “Captain Bridgeman” was Every himself, Trott denied ever knowing anything about the pirates’ history other than what they told him, adamant that the island’s population “saw no reason to disbelieve them”…

Meantime, the remnants of the passengers and crew of the Ganj-i-sawai had long ago reached Surat, and news of the depredations and atrocities that Every and his pirate crew had visited on them had reached an outraged Emperor Aurangzeb. WP tells us that the Emperor’s completely understandable wrath came at a bad time for the EIC “whose profits were still recovering from the disastrous Child’s War.”

WP continues:

The EIC had seen its total annual imports drop from a peak of £800,000 in 1684, to just £30,000 in 1695, and Every’s attack now threatened the very existence of English trade in India. When the damaged Ganj-i-sawai finally limped its way back to harbor in Surat, news of the pirates’ attack on the pilgrims—a sacrilegious act that, like the raping of the Muslim women, was considered an unforgivable violation of the Hajj—spread quickly. The local Indian governor, Itimad Khan, immediately arrested the English subjects in Surat and kept them under close watch, partly as a punishment for their countrymen’s depredations and partly for their own protection from the rioting locals. A livid Aurangzeb quickly closed four of the EIC’s factories in India and imprisoned the officers, nearly ordering an armed attack against the English city of Bombay with the goal of forever expelling the English from India.

To appease Aurangzeb, the EIC promised to pay all financial reparations, while [the English] Parliament declared the pirates hostis humani generis (“enemies of the human race”). In mid-1696, the government issued a £500 bounty on Every’s head and offered a free pardon to any informer who disclosed his whereabouts. When the EIC later doubled that reward (to £1000), the first worldwide manhunt in recorded history was underway. The Crown also promised to exempt Every from all of the Acts of Grace (pardons) and amnesties it would subsequently issue to other pirates. As it was by now known that Every was sheltering somewhere in the Atlantic colonies, where he would likely find safety among corrupt colonial governors, he was out of the jurisdiction of the EIC. This made him a national problem. Accordingly, the Board of Trade was tasked with coordinating the manhunt for Every and his crew.

By the time news of the manhunt, and the generous reward, reached the Bahamas, Every had disappeared. Toward the end of June 1696, “Every and about twenty other men sailed in the sloop Sea Flower… to Ireland… They aroused suspicions while unloading their treasure, and two of the men were subsequently caught. Every, however, was able to escape once again.” Sightings of him were reported for several years thereafter, but none ever proved reliable.

As for his crew, some 75 of them sailed to the English colonies on the North American mainland:

His crew members were sighted in the Carolinas, New England, and in Pennsylvania; some even bribed Pennsylvania Governor William Markham for £100 per man. This was enough to buy the governor’s allegiance, who was aware of their identity and reportedly even allowed one to marry his daughter…

Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, and other colonies published the proclamation authorizing Every’s arrest, but rarely went beyond this. Although harboring pirates became more dangerous for the colonial governors over time, only seven of Every’s crew were tried between 1697–1705, and all of these were acquitted.

Ancient coins taken from Ganj-i-Sawai were discovered in 2014 at Sweet Berry Farm in Middletown, Rhode Island. Later on, more coins were unearthed in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and North Carolina…

In England, meanwhile, this happened:

John Dann (Every’s coxswain) … was arrested on 30 July 1696 for suspected piracy at the Bull Hotel, a coaching inn on the High Street of Rochester, Kent. He had sewn £1,045 in gold sequins and ten English guineas into his waistcoat, which was discovered by his chambermaid, who subsequently reported the discovery to the town’s mayor, collecting a reward in the process. In order to avoid the possibility of execution, on 3 August Dann agreed to testify against other captured members of Every’s crew… Soon after, twenty-four of Every’s men had been rounded up, some having been reported to authorities by jewelers and goldsmiths after trying to sell their treasure. In the next several months, fifteen of the pirates were brought to trial and six were convicted. As piracy was a capital crime, and the death penalty could be handed down only if there were eyewitnesses, the testimony of Dann and Middleton was crucial.

Five of those convicted were hanged. Dann himself had–

escaped the hangman by turning King’s witness…In 1699, Dann married Eliza Noble and the following year became a partner to John Coggs, a well-established goldsmith banker, creating Coggs & Dann at the sign of the King’s Head in the Strand, London.

Very quickly, Henry Every’s name had been added to the veritable “pantheon” of famous pirates who had a huge cult following in English folk culture– from Francis Drake to Walter Raleigh, to Henry Morgan, and so on.

Personally, I think such adulation is very misguided. These were men, sometimes born to families of few means, who made lives and fortunes themselves on the high seas by exploiting “White” privilege and their command of weapons to force their usually very brutal will on people of color on several continents. Many, many of them, not just Henry Every were deeply involved in the shipping and exploitation of enslaved persons.

It is true that on some occasions, as with Henry Every, the political-mercantile elite in England cracked down on the “pirates.” But just as frequently– or probably even more frequently– the pirates were brought into use by the political-mercantile elite, just like today’s military’s contractors. That comment in the WP account of Every’s piracy that what he did as a pirate was very similar to what the original “Spanish Expedition” had set out to do was accurate, and very telling. And indeed, as I’ve noted in this project before, the whole financial basis for England’s emergence as a transoceanic power had been built by English pirates and semi-“licensed” privateers who preyed on the treasure fleets that Spain was hauling back from from the Americas. So if we’re against empire, then I think we have to be against these kinds of empire-building and empire-adjacent pirates, as well.