In 1634 CE, the Dutch, English, and Spanish empires all expanded their colonial grip on distant lands to some extent. In the interior of the North American continent, a French explorer Jean Nicolet may (or may not) have been the first European to to explore the area of today’s Wisconsin, pursuing the relentless search that European explorers pursued for a passable route through or around America to “the Orient.” But still, all attempts by the French to organize a robust colony-building or raiding/trading presence anywhere in the Americas, Africa, or Asia, still remained flimsy and ill-organized.

So here are the Western colonial expansion efforts that were pushed forward in 1634:

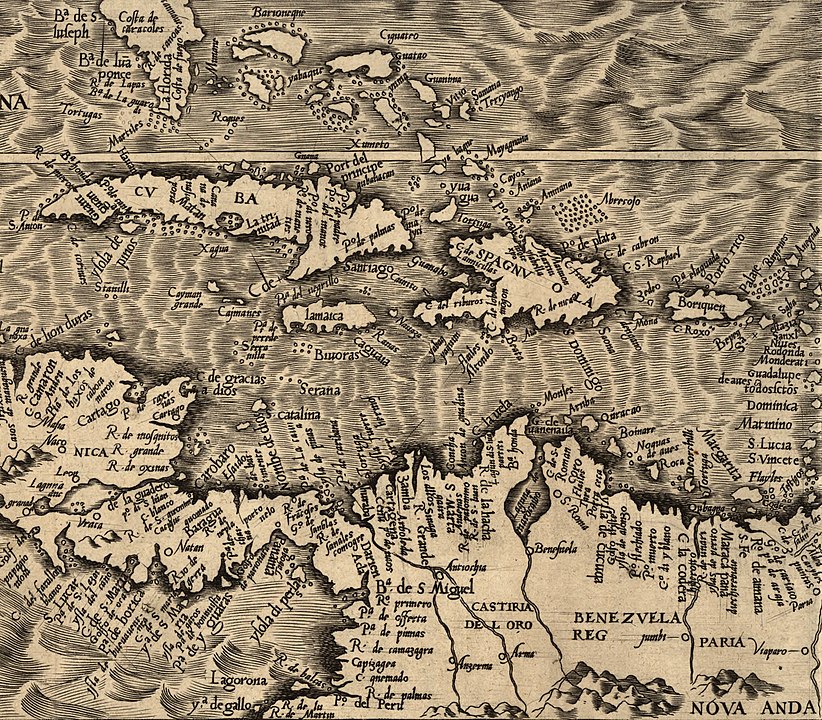

Dutch take Curaçao

Curaçao is a tiny (171 sq. miles) island lying off the north coast of today’s Venezuela. Before the arrival of the Spanish it had a population of “about 2,000” Caquetios. But this English-WP page tells us that “In 1515 almost all the Caquetios were transported [by the Spanish] to Hispaniola as slaves.”

(The banner image above is of some petroglyphs in a cave on Curaçao that seem to be the only remaining traces of the Caquetios’ heritage on the island.)

The WP page continues thus:

In 1634… the Dutch West India Company under Admiral Johann van Walbeeck invaded the island and the Spaniards there surrendered in San Juan in August. The approximately 30 Spaniards and many of the indigenous were deported to Santa Ana de Coro in Venezuela. About 30 Taíno families were allowed to live on the island. Dutch colonists started to occupy it. The WIC founded the capital of Willemstad on the banks of an inlet called the Schottegat; this natural harbour proved an ideal place for trade. Commerce and shipping—and piracy—became Curaçao’s most important economic activities. Later, salt mining became a major industry, the mineral being a lucrative export at the time. From 1662 the Dutch West India Company made Curaçao a centre for the Atlantic slave trade, often bringing slaves from West Africa there for sale elsewhere in the Caribbean and on Spanish Main.

Spain’s colonial projects in Peru, Venezuela

In 1634, the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru founded the settler-town of Borja, in the deep interior of Peru. WP tells us this:

It was named in homage to the viceroy of Peru, Francisco de Borja y Aragón. It was used as a base of support for incursions and conquests of a series of forest nations until 1640, when the Spanish presence started diminishing due to the opposition of the forest nations and systematic invasions by the Portuguese.

(I would love to know more about those “forest nations”.)

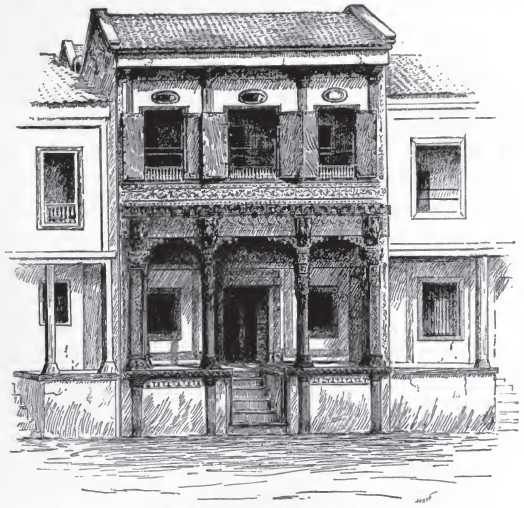

And in Coro, Venezuela, 1634 saw the completion of several decades’ worth of work on the Cathedral Basilica of St. Ann. WP tells us that it, “was among all buildings built before 1713 the most important as it will set a precedent in the architectural features for the construction of the churches of the rest of the country.”

These two Spanish colonial projects may feel to you, as they do to me, to be slightly randomly chosen. I found them from this annual Category Aggregator page on English- WP, which is all the research that I have time for now. Anyway, it is always good to remember that whatever else is going on in the world in this era, the steady drumbeat of Spanish colonial expansion and consolidation continues.

English and Portuguese colonialists do deal in India

I am always interested in the relationships between the colonial administrators “on the ground” in the non-European world and their overlords back home– whether the overlords are the monarchy, as in Spain and Portugal, or joint-stock companies or other private investors, as in England and Netherlands. (Remembering too that the the private investors back in London or Amsterdam will also have their own national-level politics to navigate with their governments– and also that in England, the monarch himself and his relatives are often themselves substantial investors in the colonial companies.)

And then, there is the matter of how inter-governmental relations “back home” in Europe affect the workings and interactions of the respective colonial administrators on the ground in the colonized world.

Regarding the Indian Ocean operations of the European empires, in particular, we also need to bear in mind the sheer chronological disconnect between what happens in European capitals and what happens in the colonies. How long might it have taken in those days take for news of a significant development in inter-governmental relations in Europe to even reach, say, Surat, Goa, or Batavia– and vice versa? In the case of the Dutch massacre of the English EIC officials in Amboyna in 1623, it seems to have taken many, many months for word to get back to London…

In 1907, when English historian William Wilson Hunter was writing his account of the EIC’s activities in the 17th century, he was very aware of the significance of that time-lag. He noted that by 1634, the English EIC had built a fairly sturdy all-India headquarters at Surat that sat astride the lines of communication the Dutch VOC needed to use to connect their all-India headquarters at Goa (south of Surat) with their outpost at Diu (north of Surat.) And similarly, the VOC’s HQ at Goa sat astride the lines of communication between the English at Surat and the English outposts on the Malabar coast– that is around the southern tip of India and on India’s eastern coast.

So, he wrote (pp.209-11),

in 1634, the [Dutch] Viceroy of Goa and the English president at Surat took the matter into their own hands and entered into direct negotiations. They signed a formal truce, which in 1635 they developed into a commercial convention on the basis of the ineffective Madrid treaty of 1630.

Two English ships were annually to obtain a cargo at Goa, two more might load at other Portuguese factories. The long promised liberum commercium between the English and Portuguese in India became an accomplished fact.

It was this talent of isolated groups of Englishmen for making their power felt in distant regions, that carried the Company through the dark days of Charles I. They turned their factory at Surat into a sea-defence of the Moghul Empire, convoyed noble and imperial devotees to the Persian Gulf on their way to Mecca, and guarded the pilgrim route. Their Dutch rivals, although much stronger in men and ships in Asiatic waters, found themselves on the Gujarat coast in the grip of the Moghul power. Nor did the Hollanders, secure of the Spice Archipelago, care so much to come to terms with the Indian Portuguese.

But while our Surat factors thus secured a strong position and earned large profits for their masters, they also, in spite of their masters, did a lucrative trade on their own account. The Company viewed with mixed emotions the rising power of its servants in the East. It had seen its president at Surat commission a squadron in 1628 to wage open war on the Portuguese. But for a local factory to make a treaty on its own account with an independent European power was a dangerous audacity. Yet, in 1636, in spite of the home directors’ alarm and half-heartedness, this convention of the Goa viceroy with the president at Surat became the basis of the settlement of the Indies.

Even Holland began to realize that, notwithstanding her Spice Island supremacy, the English understood the greater game of Indian politics better than her own servants in the East… The truth is that the Dutch governors-general at Batavia, domineering over their petty island chiefs, had the very worst training for the direction of distant factories under the irresistible Moghul emperors…