Here’s 1578 CE, the headlines then the stories:

- Portugal’s king dies in battle; succession chaos unfolds

- Ottomans start lengthy war against Safavids

- Explorers Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh set out from Plymouth

Portugal’s king dies in battle; succession chaos unfolds

Portugal’s King Sebastian had assumed the throne in 1557, aged three; and obviously the country had been ruled by regents: first his paternal grandmother, Catherine of Austria, and then his great-uncle, Cardinal Henry of Évora. According to English-WP he was raised by Jesuits and attained his majority at age 14. WP also tells us he,

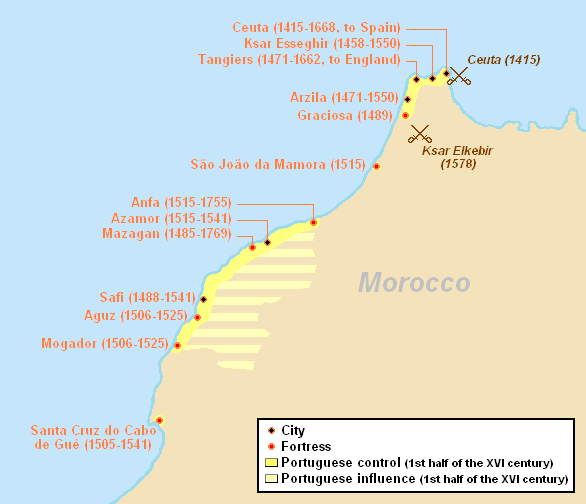

dreamed of a great crusade against the kingdom of Morocco, where over the preceding generation several Portuguese way stations on the route to India had been lost. A Moroccan succession struggle gave him the opportunity, when Abu Abdallah Mohammed II Saadi lost his throne in 1576 and fled to Portugal. After arriving, he asked for King Sebastian’s assistance in defeating his Turkish-backed uncle and rival, Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik I Saadi.

Sebastian was all in! Not so much, his uncle King Philip II of Spain who was more interested in a truce with the Ottomans.

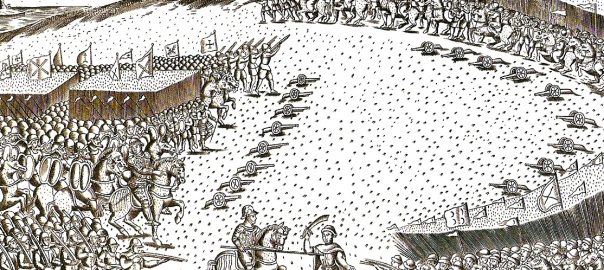

Sebastian left Lagos, Portugal with his armed fleet and Abu Abdallah in June 1578, landing in one of the Portuguese enclaves on the Moroccan coast. Sultan Abd al-Malik, who was not in good health, was awaiting them with his army, at a place called al-Qasr al-Kbir (the Big Castle.) The Portuguese side had 23,000 men and 40 cannons; the Moroccans had between 50,000 and 100,000 men and 34 cannons.

WP:

The battle ended after nearly four hours of heavy fighting and resulted in the total defeat of the Portuguese and Abu Abdallah’s army with 8,000 dead, including the slaughter of almost the whole of the [Portuguese] nobility. 15,000 were captured and sold into slavery, and around 100 survivors escaped to the coast. The body of King Sebastian, who led a charge into the midst of the enemy and was then cut off, was never found.

The Sultan Abd Al-Malik died during the battle from natural causes (the effort of riding was too much for him), but the news was concealed from his troops until total victory had been secured. Abu Abdallah attempted to flee but was drowned in the river. Because of the deaths during the fighting of Sebastian, Abu Abdallah, and Abd Al-Malik, the battle became known in Morocco as the Battle of the Three Kings.

(The banner image above is a Portuguese drawing of 1629 laying out the order of battle. Portuguese to the left.)

The battle was a disaster for the Portuguese from many points of view. Not only had Sebastian rushed headlong into a battle for which he and his troops were clearly not prepared, but he had also failed to take the essential precaution of leaving an heir or two behind him. There was more than a hint the guy was gay, though the story was that he had not married “because of his piety.” (There have been numerous gay rulers around the world who nonetheless did their bit for the dynasty by producing an heir… Him, not.)

So the succession passed to the same Great-Uncle Henry who had been his regent… And Uncle Henry being a cardinal, he had not produced any heirs either (and would only live a further 18 months anyway.) What will happen to the monarchy of Portugal? You’ll have to read on to find out…

And by the way, the political situation on the Moroccan side was quite a lot better. WP again:

Abd Al-Malik was succeeded as Sultan by his brother Ahmad al-Mansur, also known as Ahmed Addahbi, who conquered Timbuktu, Gao, and Jenne after defeating the Songhai Empire.

The Moroccan army which invaded Songhai in 1590-91 was made up mostly of European captives, including a number of Portuguese taken prisoner at the battle of Alcácer Quibir.

Strangely, though, the figure of Sebastian seems to have lived on for a long time after 1578 in some portions of Portuguese mythology:

In the long term, many myths and legends about Sebastian appeared, the principal one being that he was a great Portuguese patriot, the “sleeping king” who would return to help Portugal in its darkest hour (similar to the Britons’ King Arthur, the German Frederick Barbarossa or the Byzantine Constantine XI Palaeologus).

He came to be known by symbolic names: O Encoberto (The Hidden One) who would return on a foggy morning to save Portugal, or as O Desejado (The Desired One). Even as late as the 19th century, “Sebastianist” peasants in the town of Canudos in the Brazilian sertão believed that the king would return to help them in their rebellion against the “godless” Brazilian republic…

Ottomans start lengthy war against Safavids

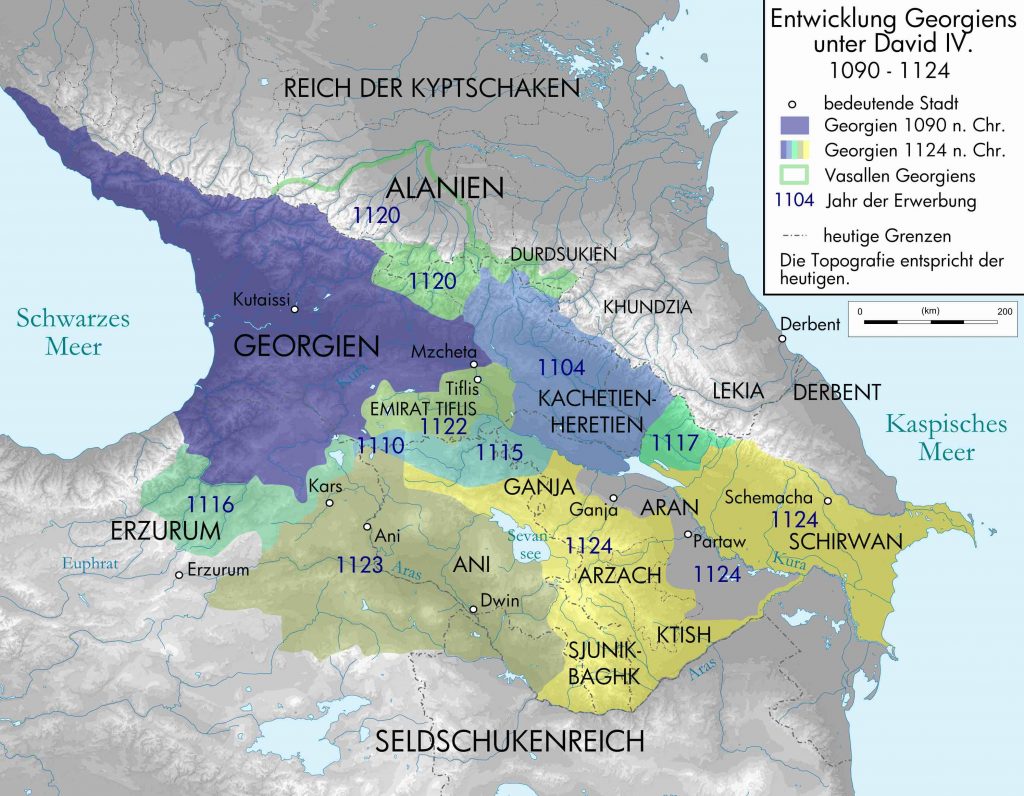

Two years ago, we left the Safavid capital Qazvin where the Shah Tahmasp had died, leaving his own untidy succession situation. And guess who was waiting at the gates of the empire waiting to pounce? The Ottomans. These two sizeable Muslim Empires had been formally at peace since the Treaty of Amasya in 1555– but actually, in the two years since 1576, the Ottomans had already been nibbling away at the far northwest edge of the Safavid Empire. And now in 1578 they took Tiflis, which was in the east of Georgia, and then Shirvan (further east.) Then the seizure of much of Georgia gave the Ottomans direct land connectivity with their allies the Crimean Tartars.

The Ottoman-Safavid war of the years that followed was protracted, especially given the extreme difficulty both sides had in imposing their will on the mountainous areas of the Caucasus. This war would last till 1790…

Explorers Humphrey Gilbert, Walter Raleigh set out from Plymouth

Whoa, here come two more of those grifters, charlatans, sadists, and renegades who made up the vanguard of England’s empire under Elizabeth!

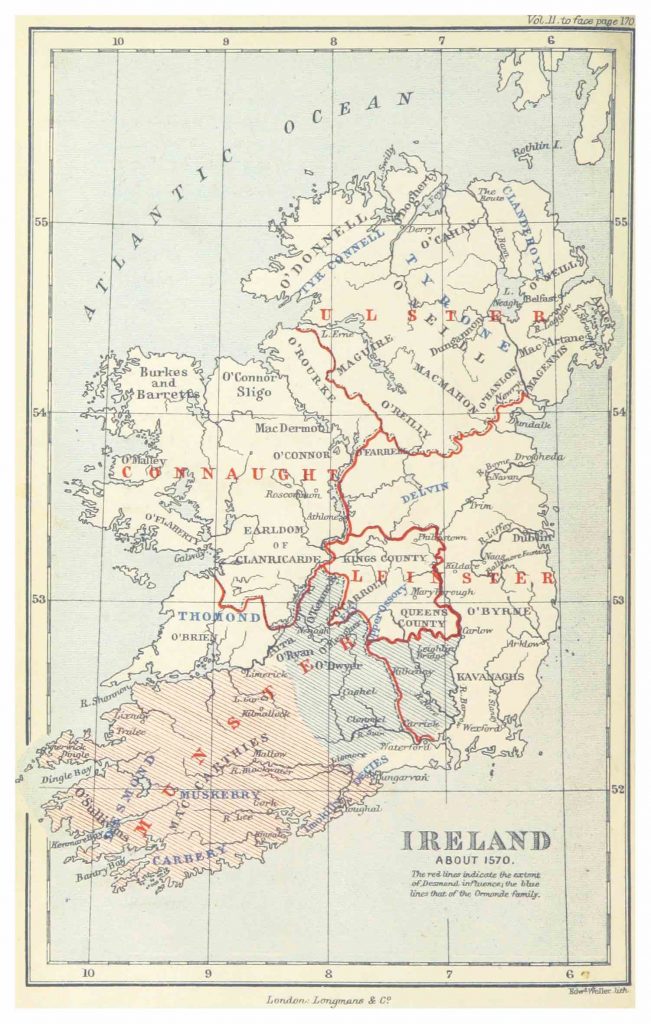

Sir Humphrey Gilbert, born 1539, is described in English-WP as “a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America and the Plantations of Ireland.” Chronologically speaking, the Plantations of Ireland came far earlier than North American colonies. But it’s certainly worth remembering the close connection between those two endeavors.

In 1567, Gilbert had been appointed Governor of Ulster and started serving as a member of the Irish Parliament. He played a big role in planning and fighting for the (Protest, English) “Plantations” (colonial settlements) in the provinces of Ulster, Munster, and Leinster and in 1569 took a big part in putting down the first “Desmond Rebellion” by Irish nationalists, in Munster.

During the three weeks of this campaign, all Irish were treated without quarter and put to the sword, including women and children. A gruesome spectacle was devised by Gilbert to cow the rebel supporters, utilising the decapitated heads of his Irish enemies:

“The heddes of all those (of who sort soever thei were) which were killed in the daie, should be cutte off from their bodies and brought to the place where he incamped at night, and should there bee laied on the ground by eche side of the waie ledying into his owne tente so that none could come into his tente for any cause but commonly he muste passe through a lane of heddes which he used ad terrorem…[It brought] greate terrour to the people when thei sawe the heddes of their dedde fathers, brothers, children, kindsfolke, and freinds…”

Gilbert explicitly advocated the killing of Irish non-combatant women and others under the following rationale;

“The men of war could not be maintained without their churls and calliackes, old women and those women who milked their Creaghts (cows) and provided their victuals and other necessaries. So that the killing of them by the sword was the way to kill the men of war by famine.”

In 1570, he returned to England, became a member of the English parliament, married, and had many sons. In 1572, he went to the Netherlands to fight with the Sea Beggars.

In 1578, he and his half-brother Walter Raleigh received “Letters Patent” from Queen Elizabeth to sail to North America and explore the idea of founding a colony there. (Throughout his life, Raleigh was as deeply engaged as Gilbert in brutally putting down anti-colonial resistance movements in Ireland.)

In November 1578, the two men set sail with a fleet of seven vessels from Plymouth in Devon, bound for North America.

That venture was not a success. The little fleet was scattered by storms and forced back to port some six months later. “The only vessel to have penetrated the Atlantic to any great distance was the Falcon under Raleigh’s command.”

They would be back…