On Monday, I wrote about the involvement of Quakers in William Penn’s settler-colonial project in Turtle Island in the 17th century CE. Now, I want to fast-forward to the early 19th century CE, and start looking at the involvement of Baltimore Quakers in various stages of the ongoing westward expansion of the project, which was now being carried out under the auspices of the government of the “United States of America”, whose 13 member colonies had undertaken their Ian Smith-style “Unilateral Declaration of Independence” against the metropole back in 1776.

How did communities of Quakers end up in the Baltimore region? I’ll have to leave that for another day. Important here only to note that “Baltimore Yearly Meeting” (BYM) is one of a number of big east-coast “Yearly Meetings” in the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). The local meetings that constitute it are located in Virginia, Maryland, and a portion of Pennsylvania… in general, along the watershed of the Chesapeake Bay, including the Susquehanna River which flows south into the Chesapeake.

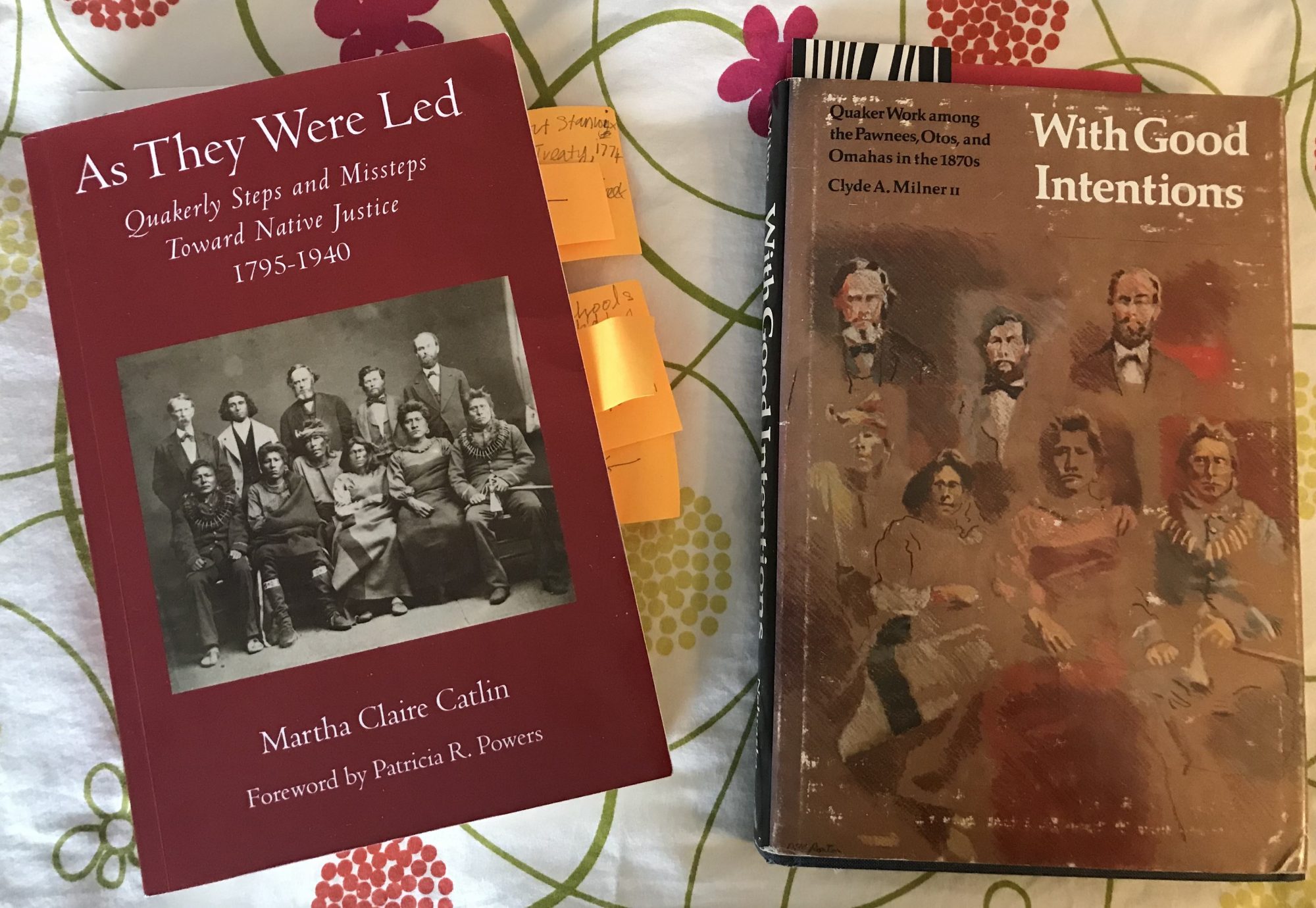

So since the Quaker meetings I’m associated with are both part of BYM, I’ve recently been reading a couple of interesting books about the work that BYM’s Indian Affairs Committee (BYM-IAC) has been doing since it was first formed in 1795. Here they are:

The book on the left, just published by a small Quaker press, is an account of the work of the BYM-IAC between its founding in 1795 (!) and 1940, written by a current member of the committee. It is based almost wholly on the committee’s own records and provides sadly little broader context regarding what the Native Americans were undergoing at that time in terms of lengthy strings of broken “treaties” with the U.S. government, assaults on them by the U.S. military, the relentless pressure of the waves of “White” settlers who were being funneled into their lands, and so on…

The book on the right, published by Nebraska University Press in 1982, looks in more detail at the records of the BYM-IAC and the IAC’s of two other Quaker YM’s in the years from 1869 through 1877 — when those committees were actually contracted by the federal government in Washington DC to run the “Indian Affairs” of the three Indigenous Nations named on the cover, on behalf of first the U.S. War Department and then the Department of the Interior. BYM’s IAC took responsibility for the Pawnee Nation and a handful other smaller groups.

Clyde Milner’s account is deeply researched, relying on US government records, the records of the BYM-IAC, local (Nebraska) news accounts, and where he can find them, any records left by the Pawnee themselves. It makes for extremely troubling reading. As Martha Catlin also admits, the idea that some (quite possibly “well-intentioned”) Quakers–who were themselves “White” colonial settlers in more easterly parts of Turtle Island–could in some way mitigate or end the harm that the massive influx of “White” settlers was inflicting on the Pawnee and their Indigenous neighbors was chimerical from the get-go.

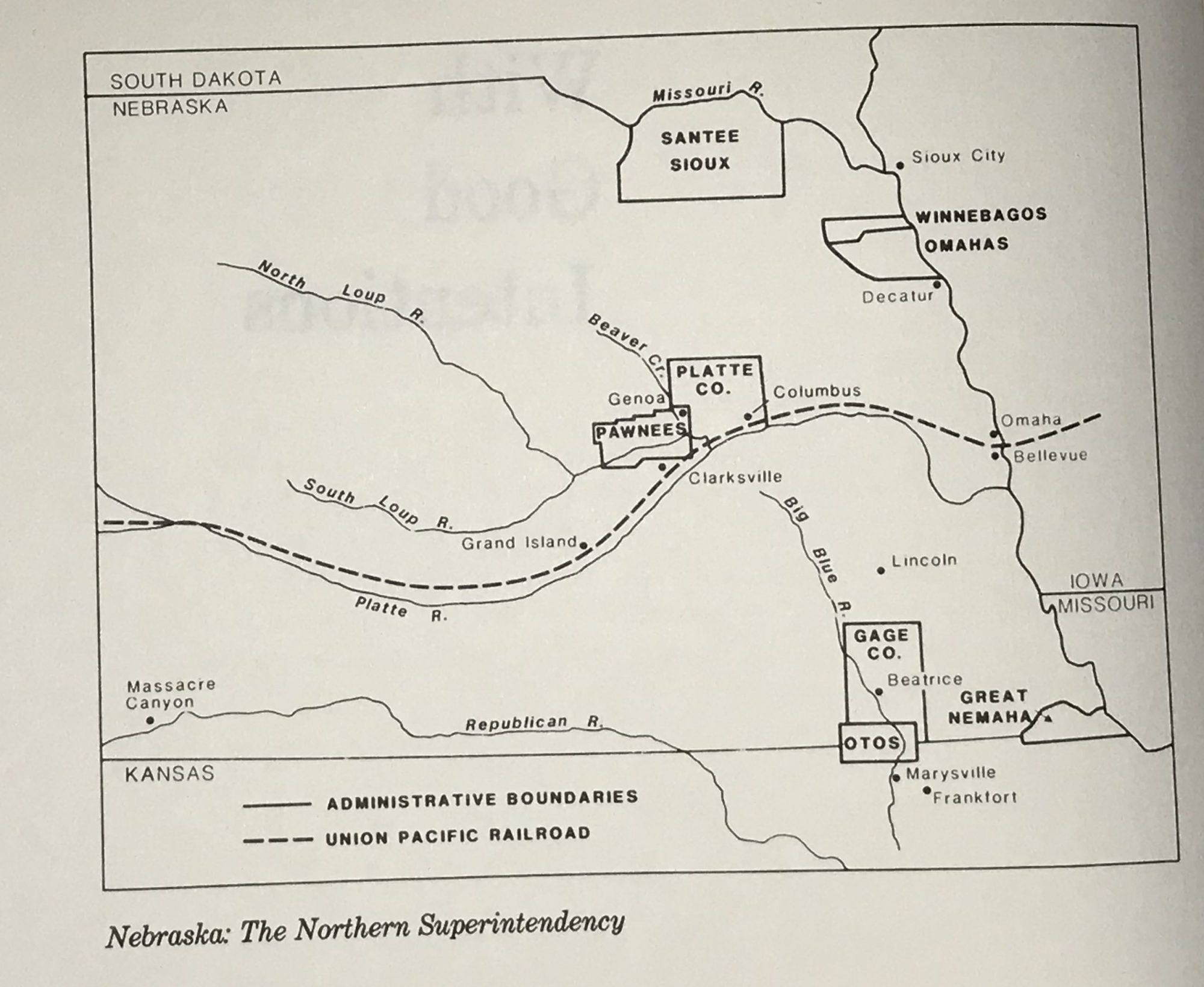

Basically, the Pawnee and their Indigenous neighbors were being corralled onto ever smaller portions of terrain as all the good land in the region was being grabbed and “settled” by the White newcomers. Milner has a map of the various tiny reservations that the BYM-run “Northern Superintendency” in Nebraska was responsible for:

I still haven’t finished reading his account. But what Martha Catlin tells us about what happened in 1873-74 is deeply, deeply troubling. In August 1873, some Sioux who had long been battling the Pawnees launched a devastating raid against a Pawnee encampment at a spot later called Massacre Canyon, that led to the killing of 20 Pawnee men, 39 women, and 10 children… also, the loss of more than 100 horses and the dried meat of 800 buffalo. (Catlin, p.231.) The Quaker Indian Agents tasked with “civilizing” the Pawnee had urged them not to arm themselves; and the local units of the U.S. military did nothing to protect them. All the Indigenous people in the area at the time were extremely hard-pressed as a result of U.S. military raids, land seizures, the U.S. forces’ mass killings of buffalo and spread of devastating European diseases; also plagues of grasshoppers, etc. And you can bet the settler colonialists and their military were generally quite happy to see the different Indian nations fighting amongst themselves….

The following year, the Pawnee survivors of the massacre took the difficult decision to remove themselves southward to Oklahoma, where they thought they could be safer. 1,400 of them set out, to join the 360 Pawnee who were already in Oklahoma, which was then called “Indian Territory”. However, by 1877, 900 of them had died there, seemingly from malnutrition. The BYM Quaker who was overseeing all the BYM-IAC’s activities in the region reported that “The movement of the Pawnees from Nebraska to the Indian Territory has been disastrous in its results.” (Quoted at Catlin, p.241.)

Clyde Milner’s choice of a title for his book, “With Good Intentions”, was evidently made with some mixture, in unknown proportions, of irony and a degree of forgiveness for the actions of those Quakers who were government “Indian Agents” in Nebraska. “With Good Intentions” is a theme that runs through much of the (still sparse) reflection that today’s Quakers here in Turtle Island engage in when they look at the actions that their (our) Quaker forerunners undertook toward the Indigenes of this land.

I have two questions about these Quakers’ use of this theme:

- Can we honestly know what the “intentions” of people of past generations actually were? We may know what they wrote in their records. But what did they leave out of, or gloss over, in those records? (And even in the records they did leave, there was much that should in any generation be considered troubling, such as their evident disdain for Native culture and their insistence that the only viable path forward for Native Americans would be through “civilizing” them…)

- If we adopt, as I believe we should, a victim/survivor-centered notion of justice, why should the moral quality of the “intentions” of those earlier perpetrators matter at all? Should we not instead focus on the effects that those perpetrators’ actions had on populations and individuals who were much more vulnerable than they and who were oftentimes at their mercy?

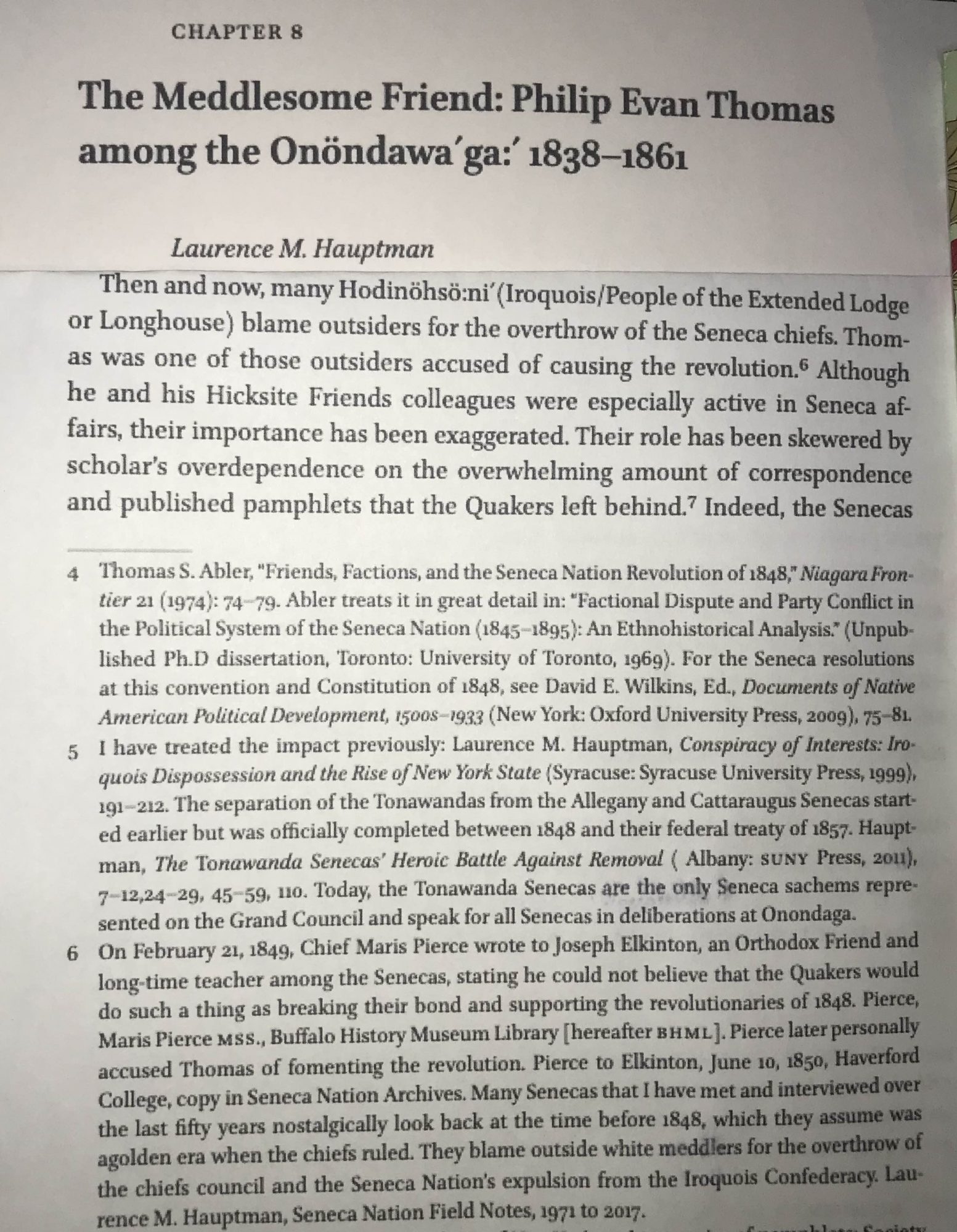

In this regard, I’d like to focus on the “intentions” of Mr. Philip E. Thomas, a Quaker from Baltimore who joined the BYM-IAC in 1803 and at some point thereafter became its clerk (chairperson.) He served for many years, perhaps decades, in that position, including during the years 1838-61 when BYM-IAC was very involved in various endeavors involving the Seneca and other Indigenous peoples of upper New York State.

Basically, according to Martha Catlin’s account, the BYM-IAC’s activities in the period she covered (1795-1940) comprised four major sets of endeavors. Their activities among the Pawnee and others in Nebraska constituted the fourth of those phases.

In the first phase, the BYM-IAC collected money from Friends Meetings in the BYM area in order to “compensate” the previous Native inhabitants of the areas in the Shenadoah Valley in which, once the colonists’ UDI crowd had managed to expel the British, numerous pro-UDI Quakers from further east in today’s Virginia had settled. (The British, it should be noted, had tried to limit the White settler-colonial project to the line of the Blue Ridge Mountains. But once they were expelled, thousands of settlers rushed west into the fertile Shenandoah Valley, displacing the area’s previous Indigenous inhabitants and sending them to the west.)

In its early years, the BYM-IAC, emulating William Penn more than a century earlier, had tried to find the heirs of those displaced and give them money, so that they (the settlers) could claim that their forceful seizure of the lands west of the Blue Ridge had been a series of “purchases”. But they could not find any heirs! It’s not clear how hard they had tried….

In the second phase in its existence, the BYM-IAC sent emissaries over the next few ridges of the Appalachian Mountains into Ohio– perhaps originally to try to find those displaced from the Shenandoah, but anyway, also very happy to scope out everything they could about the situation in the Ohio Valley. (Philip Thomas, not yet the IAC clerk, was one of those emissaries.) In that second phase of the IAC’s activities, it made some initial contacts with Indigenous leaders in the Ohio Valley, whom it invited to come to Washington DC. The capital of the U.S. government had by then been moved from Philadelphia to Washington, a town that lay in the BYM area; and the BYM-IAC took it upon itself to be a go-to address for Indigenous leaders visiting federal government officials.

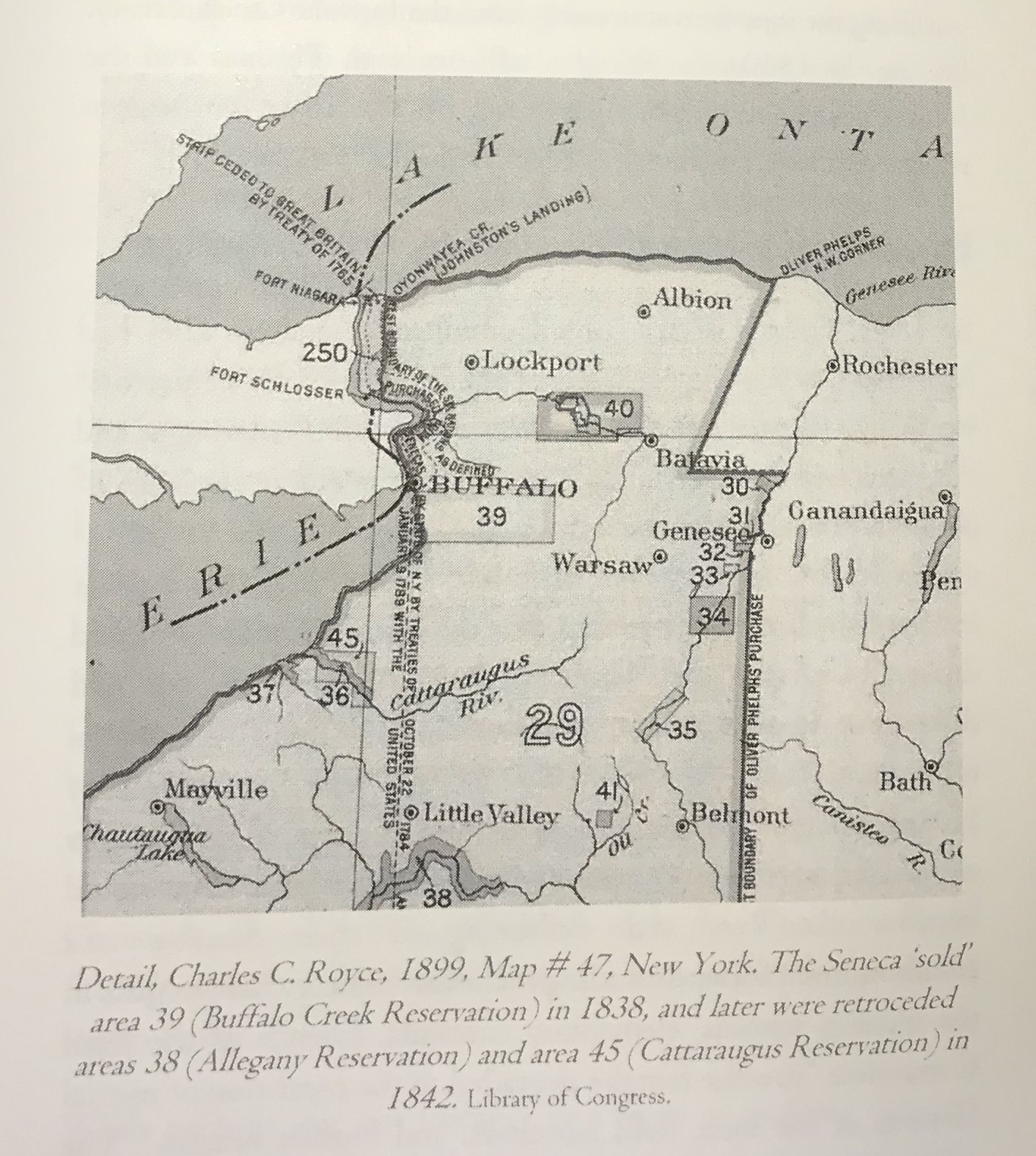

The third phase of the BYM-IAC’s activities was undertaken when Philip Thomas was its clerk. In this phase, which ran 1838-61, BYM-IAC joined the IAC’s of a number of other east-coast Yearly Meetings to try to do “good works” with the Indigenous Nations of northern New York. This phase apparently came to an end only when the intra-settler US “civil war” erupted in 1861, at which point the attention of most of the philanthropically inclined among the east coast Quakers turned to trying to support those impacted by the war, and to aiding the newly freed African Americans of the southern states.

1861 was also the year that Philip Thomas died. English-Wikipedia tells us this about him:

His efforts to help Native Americans earned him the title of “Hai-wa-nob” (the Benevolent One) from the Swan tribe of the Seneca people. Thomas was the representative to Washington for the Six Nations of Indians.

Another source, however, gives a much different and more detailed summary of Thomas’s work with the Seneca. This was Laurence M. Hauptman, writing in Ch. 8 of this outrageously over-priced volume. I could only read the first two pages of Hauptman’s chapter online there. But its title, and the judgment he expresses at the top of p.137 (as shown here), are very telling. And the nature and quality of his footnotes are impressive…

However, I don’t want to spend too much time here looking at Thomas’s record with the Seneca. Rather, I want to focus on an aspect of his life that is mentioned in passing (or in footnotes) in Catlin’s book on a couple of occasions, but that I think deserves considerably more attention than she ever gave it.

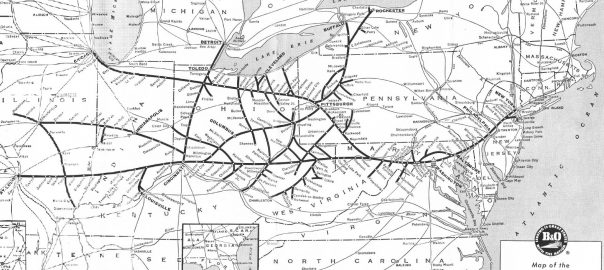

Philip Thomas, the clerk of the BYM’s Indian Affairs Committee for many years, was also, for many or all of those same years, a commissioner of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Commission (C&O) and the founding president of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company (B&O). The B&O Company won its charters from the state legislatures of Virginia and Maryland in 1827. Thomas resigned his commission with the C&O Canal the following year, betting rightly that the still-new transportation technology of railroads would be more useful to the project of supporting the settlers’ western expansion than canals could ever be.

Think about it.

The B&O Railroad, like the C&O Canal before it, was a major infrastructural project designed from the get-go to support the westward expansion of the settler-colonial entity. The B&O was planned and undertaken by the merchants and financiers of Baltimore with zero record that they undertook any consultation at all with the “Indians” whose lands would be expropriated, despoiled, and ground under the heel of the colonists brought into their lands by this large, well-funded, iron machine.

English-WP tells us this about the B&O:

The railroad did not reach the Ohio River until 1852, 24 years after the project started. Yet the Ohio was from the beginning the destination the railroad was seeking to link with Baltimore, at the time a railroad center. By crossing the Appalachian Mountains, a technical challenge, it would link the new and booming territories of what at the time was the West—including Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky—with the east coast rail and boat network, from Maryland northward…

…

The fast-growing port city of Baltimore, Maryland, faced economic stagnation unless it opened a route to the western states. On February 27, 1827, twenty-five merchants and bankers studied the best means of restoring “that portion of the Western trade which has recently been diverted from it by the introduction of steam navigation.”[1][2] Their answer was to build a railroad—one of the first commercial lines in the world.[3]

Their plans worked well, despite many political problems from canal backers and other railroads…

The railroad grew from a capital base of $3 million in 1827 to a large enterprise generating $2.7 million of annual profit on its 380 miles (610 km) of track in 1854, with 19 million passenger miles. The railroad fed tens of millions of dollars of shipments to and from Baltimore and its growing hinterland to the west, thus making the city the commercial and financial capital of the region south of Philadelphia.

Two men—Philip E. Thomas and George Brown—were the pioneers of the railroad…

Are these raw facts not more important than any quibbling about the “intentions” that Philip Thomas brought to his 23-plus years of volunteer work on the BYM-IAC? Also, how might these raw facts about his involvement in (leadership of!) a major component of the settler-colonial project in Turtle Island affect our understanding of what Philip Thomas’s “intentions” might really have been? Good questions to ponder, I think…

The map at the top of this blog post is a map of the B&O railroad in 1961. (After that, it got taken over by the CSX railroad. I have traveled on many of its lines, without until now understanding the involvement in its building of an apparently still-respected Baltimore Quaker…)