In 1678 CE, the world of European imperialisms saw several developments of note. In Portuguese-controlled Brazil, the royal leader of an enclave of escaped, previously enslaved Kongolese tried to negotiate peace with the colonial authorities then faced an internal challenge. In Europe, the two empire-building powers France and the Dutch UP’s finally made peace after six years of war on land and sea. Meantime, the Dutch political/commercial authorities in distant Java launched a war that almost eliminated an Indigenous opponent, while in the Caribbean a whole French fleet ran aground on a reef due to poor navigation– but then, a French privateer picked up the pieces.

Quite a year.

Scroll on down to read all these stories!

Escaped, formerly enslaved Ganga Zumba tries to do a deal with colonial administration in Brazil

This is a continuation, 12 years later, of a story that I started tracking back in 1665, when the Portuguese in Kongo had beaten a large Indigenous force led by Kongo’s King Antonio I at the Battle of Mbwila, and several members of the Kongolese royal family had been captured, enslaved, and transported to work in a sugar-cane plantation (engenho) in northeast Brazil. And once there, as this WP page said,

They led a rebellion at the engenho, escaped, and later formed their own kingdom of Quilombo dos Palmares, a Maroon nation which controlled large areas of northeast Brazil during the Dutch-Portuguese War.

So now, let’s catch up with what happened to them in Brazil. This WP page on Ganga Zumba, aka Nganga Nzumbi, tells us this:

Ganga Zumba, his Brother Zona and his sister Sabina (mother of Zumbi dos Palmares, his nephew and successor) were made slaves at the plantation of Santa Rita in the Portuguese Captaincy of Pernambuco in what is now northeast Brazil, which at the time was controlled by the Dutch. From there they escaped to Palmares.

A quilombo or mocambo was a refuge of runaway slaves who were forcibly brought to Brazil… [who] escaped their bondage and fled into the interior of Brazil to the mountainous region of Pernambuco. As their numbers increased, they formed maroon settlements.

Gradually as many as ten separate mocambos had formed and ultimately coalesced into a confederation called the Quilombo of Palmares, or Angola Janga, under a king, Ganga Zumba or Ganazumba, who may have been elected by the leaders of the constituent mocambos. Ganga Zumba, who ruled the biggest of the villages, Cerro dos Macacos, presided the mocambo’s chief council and was considered the King of Palmares. The nine other settlements were headed by brothers, sons, or nephews of Gunga Zumba. Zumbi [a nephew] was chief of one community and his brother, Andalaquituche, headed another.

By the 1670s, Ganga Zumba had a palace, three wives, guards, ministers, and devoted subjects at his royal compound called Macaco. Macaco comes from the name of an animal (monkey) that was killed on the site. The compound consisted of 1,500 houses which housed his family, guards, and officials, all of which were considered royalty. He was given the respect of a Monarch and the honor of a Lord.

In 1678 Zumba accepted a peace treaty offered by the Portuguese Governor of Pernambuco, which required that the Palmarinos relocate to Cucaú Valley. The treaty was challenged by Zumbi, one of Ganga Zumba’s nephews, who led a revolt against him. In the confusion that followed, Ganga Zumba was poisoned, most likely by one of his own relatives for entering into a treaty with the Portuguese. And many of his followers who had moved to the Cucaú Valley were re-enslaved by the Portuguese. Resistance to the Portuguese then continued under Zumbi…

France and Dutch UP’s make peace in Europe

France and the UP’s have, since 1672, been locked into a vicious war which ensnared many other key powers in Western Europe. Finally, in August 1678, these two protagonists decide to call it quits and make peace, and over the 15 months that follow the subsidiary conflicts all get resolved as well. (Though the original bilateral peace, the Treaty of Nijmegen, doesn’t hold together completely… )

This page on Wikipedia tells us that peace negotiations had begun as early as 1676; that the bilateral Franco-Dutch treaty “placed the northern border of France very near its modern position”; and depressingly that “The treaties did not result in a lasting peace.”

And indeed, just four days after the signing of the treaty there was a big battle between the armies of the two countries at St. Denis, near Mons in today’s Belgium, in which the the French side lost 4,000 killed or wounded while the Dutch side (UP’s + Spanish Netherlands, fighting together) lost between 4,500 and 5,000 killed or wounded… and the battle was deemed to be “inconclusive”!

(The banner image above is a representation of the Battle of St. Denis.)

Well, all that fighting of the preceding six years had had pretty miserable effects for the peoples of the war-zone and the numerous belligerent parties. One political actor that was pretty happy to see it carrying on was the English, who had originally joined the war in 1672 but exited it pretty speedily thereafter. And one aspect of the matter that particularly delighted the investors, bullies, and ne’er-do-wells who ran England’s often struggling East India Company (EIC) was that it significantly diminished the ability of those other two imperial contenders to compete harshly in the race for control over Indian Ocean sea-routes.

In 1907, the very pro-EIC English historian Alfred Comyn Lyall would write this about the way the English decisionmakers (basically, King Charles II and his brother the Duke of York) had viewed the lethal, large-scale fighting that continued in continental Europe during the 1670s (pp.39-41):

In 1671, accordingly, England did join France in a war [against the UP’s] which ended, so far as we were concerned, in 1674, when the Dutch agreed to salute the English flag in the narrow seas and to refer all commercial differences to arbitration. Louis XIV, on the other hand, went on capturing town after town on the Flemish border; his great armies were overrunning Holland; and the Prince of Orange had declared that he would die in the last ditch. Finally, when the English had made a defensive treaty with Holland to save her from ruin, a general peace was ratified at Nimeguen in 1678, on terms very favourable to France, who retained many of the barrier towns in the Netherlands.

The upshot of these long continental wars was manifestly to strengthen England and to weaken Holland. In 1677, when the French invasion had thrown the Dutch into peril and distress, the commerce of England was prospering wonderfully. Moreover, the truce of 1678 was soon broken by fresh hostilities; and from that time up to the end of the century the French king was entirely engrossed in his ambitious and extravagant wars, while the Dutch were fighting desperately for their existence; so that the only two maritime powers from which England had anything to fear in the East were entangled in a great struggle on the European Continent. From these contests Holland emerged, at the Peace of Ryswick in 1697, with enfeebled strength, with her commerce severely damaged, and with her resources for distant expeditions materially reduced. But the Dutch had done much injury to the earliest French settlements planted under Colbert’s auspices in the East Indies; and France had been so much occupied on the land, particularly when the fortune of war began to turn against her, that she was now incapacitated from pursuing Colbert’s wise and far-reaching schemes of commercial and colonial expansion. Her naval development was checked and her maritime enterprise took no fresh flight until after the Peace of Utrecht in 1713. In short, the French and Dutch had mutually disabled each other, to the great advantage, for operations beyond sea, of the English, who thenceforward begin to draw slowly but continuously to the foremost place in Asiatic conquest and commerce.

From this period of great Continental wars in Europe we may date the beginning of substantial prosperity for our East Indian trade; for it was then that the English made good their footing on the Indian coasts.

But in 1678, the Dutch were still far from impotent in East Asia. Read on…

Dutch VOC leads big campaign in Java

The Dutch VOC trading company had had its “Asia region” headquarters at Batavia on the north coast of the large East Indies island of Java for many decades. Throughout the 17th century, the Mataram Sultanate had come to dominate much of Java. As this page on WP tells us:

What happened in Mataram was of a great importance to the VOC, because Batavia could not survive without food imports from central and eastern Java. The VOC also depended on timber from the Javanese north coast in order to build and repair ships for its trading fleet, and for new construction in the city.

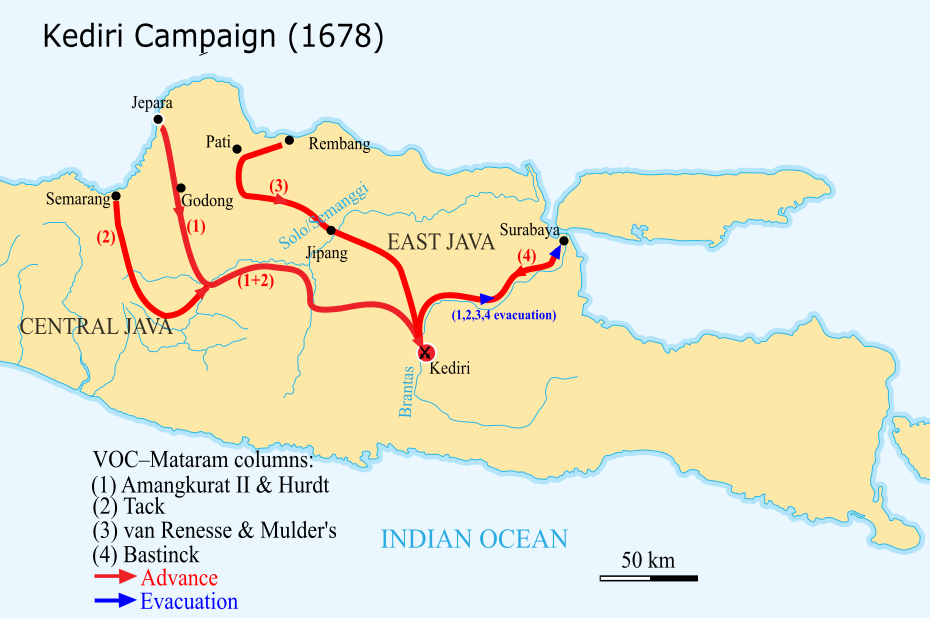

In 1674, a prince called Trunajaya had launched a rebellion against the Mataram Sultan Amangkurat I. In early 1677 Amangkurat concluded an alliance with the VOC to help him suppress the rebellion. The VOC sent a fleet from Batavia (toward the west end of Java’s north coast) along to Surabaya, some 250 miles east along the same coast, where Trunajaya had established his court. They drove him out of these and he retreated to Kediri, deep in the interior, establishing a new headquarters there– and from there he was able to sack the Mataram capital of Plered.

Obviously, this was very bad news for the VOC, whose inability to give effective help in suppressing Trunajaya might have even threatened Amangjurat’s confidence in them altogether! Also, during the Mataram retreat from Plered, Sultan Amangkurat I died.

WP picks up the story:

He was succeeded by his son, Amangkurat II, who had fled with his father. Lacking an army, a treasury, and a working government, Amangkurat II went to Jepara, the headquarters of a VOC fleet under Admiral Cornelis Speelman, and in October signed a treaty renewing their alliance. In exchange for helping Mataram against his enemies, Amangkurat promised to pay the VOC 310,000 Spanish reals and about 5,000 tonnes (5,500 short tons) of rice. This covered payments for all previous VOC campaigns on Mataram’s behalf up to October. In further agreements, he agreed to cede districts east of Batavia, as well as Semarang, Salatiga and its surrounding districts, and awarded the company a monopoly on the imports of textiles and opium into Mataram, as well as on the purchase of sugar from the Sultanate.

The Mataram-VOC joint allies advanced toward Kediri from the coast in three columns. They commanded significant strength:

When the campaign began, the Mataram forces numbered 3,000 armed men and 1,000 porters. As the march progressed, new troops were levied along the way, and some lords declared their allegiance to the Mataram King, enlarging the royal army to 13,000 men. However, desertion reduced this army again, and during the assault on Kediri, the Mataram forces had only about 1,000 armed men. The initial 3,000 men were armed with pikes, but some of the later levies had firearms.

Before the start of the campaign, the VOC had 900 soldiers on Java’s north coast, deployed as garrisons in various towns. An additional expeditionary force of 1,400 arrived at the start of the campaign. As the army marched, it was joined by the garrisons in the cities it passed. Indonesians of various ethnicities made up the majority of the VOC forces; European soldiers, marines and officers made up a minority. Desertion and disease caused the forces to dwindle—at the time of the assault on Kediri, the VOC had 1,750 men and only 1,200 joined the assault. The VOC-Mataram forces had artillery, but due to the limited ammunition, it was saved for the final assault.

That was a significant ground-combat ability the Dutch were deploying in Java.

By November 25, the different columns were converging on Kediri, which was also not a trivial place:

The city was about 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) in circumference, defended by 43 artillery batteries and by walls up to 6 metres (20 ft) high and 2 metres (6.6 ft) thick. According to [Australian historian M. C.] Ricklefs, Kediri’s fortifications “seem not to have been inferior to contemporary European fortresses”. Hurdt’s column entered the city from the east, while de Saint Martin entered from the northwest. As was common in Javanese siege warfare of the time, the assault was accompanied by cannon fire, as well as loud yelling and the playing of drums and gongs to weaken the defender’s morale. De Saint Martin arrived first in the alun-alun (city square) of Kediri, near Trunajaya’s residence. The defenders put up a fierce resistance. Four VOC companies, under the command of Tack, engaged in “courtyard-by-courtyard” fighting to conquer Trunajaya’s residential compound in the city centre. VOC troops made use of hand grenades which proved very useful in city fighting.

The loyalist [Mataram-VOC] troops were victorious. Trunajaya fled southwards into the countryside, and his side suffered heavy losses. The VOC suffered light casualties of 7 dead and 27 wounded.

Well, it turned out the war was not over. It was not till the early 1680s that Trunujaya’s forces had been completely vanquished. But after a rocky start, the VOC had proven its ability to fight well in the interior of Java.

French admiral takes a wrong turn in the Caribbean and…

Jean, Comte d’Estrées had joined France’s new navy in 1668 “at the request of his friend Colbert.” Then his naval career took off:

His first campaign was in the Caribbean. He returned four times, becoming the French naval specialist in the region.

During the Franco-Dutch War, he was put in command of the French fleet which would fight alongside the English fleet against the Dutch. He participated on board the Saint Philippe in the Battle of Solebay in 1672 and the next year on the la Reine, in the Battle of Schooneveld and the Battle of Texel.

In 1676 and 1677, he conquered Gorée [in West Africa], Cayenne and Tobago, destroying the Dutch fleet based there.

But then this:

Following his successes at Cayenne and Tobago, d’Estrées planned to attack the Dutch at Curaçao island. His fleet—12 men of war, 3 fireships, 2 transports, a hospital ship and 12 privateers—met with disaster, losing 7 of the men of war and 2 other ships when they struck reefs off the Las Aves archipelago due to a navigational error on 11 May 1678, a week after setting sail from Saint Kitts.

According to the captain of d’Estrées flagship Terrible, Nicholas Lefèvre de Méricourt, d’Estrées was solely at fault and had abandoned the ship to its fate. Navy minister Seignelay received other reports, including d’Estrées own, which told a different story and one more favourable to the unpopular admiral…

With the loss of half his fleet, d’Estrées had to return to France. He was exonerated of personal responsibility for the disaster.

However, the broken ships were not completely wasted. A French privateer (= pirate-for-hire) called Michel de Grammont was able to salvage six of them, and their men. And in June 1678 he did this:

De Grammont landed his men in Spanish-held Venezuela and captured Maracaibo, as well as several smaller towns including Gibraltar [in Venezuela], penetrating as far inland as Trujillo. For the next six months the pirates plundered the entire region. This was followed by another successful raid on the Venezuelan port of La Guaira, captured in a daring night attack, though the buccaneers only escaped with difficulty when attacked by a larger Spanish force.