The biggest development of 1670 was a secret treaty that England’s King Charles II concluded with France’s King Louis XIV. This treaty had huge effects over the following years. It was a masterpiece of diplomatic ingenuity wrought by Louis’s very able First Minister Jean-Baptist Colbert and his younger brother Charles, Louis’s ambassador in London. The diplomatic prowess shown by Louis and the Colberts was matched and indeed undergirded by long-continuing improvements in (and centralization of) both France’s internal administration and its military forces… All of those capabilities together prepared France for a much larger and more significant entry into the project of transoceanic imperialism than any it had been able to sustain before.

Therefore, today’s bulletin will focus primarily on France. Before we travel there, though, a handful of other quick new items:

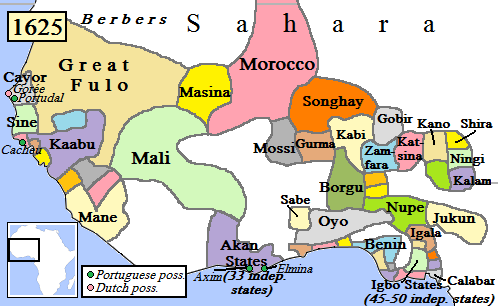

End of the Malian Empire

In its heyday in the 14th century CE, the Malian empire had stretched across a large swathe of West Africa, controlling some very profitable trans-Saharan trade-routes including for gold, sandalwood, salt, and enslaved persons, and building and sustaining several notable libraries and places of learning. (Muslim forms of slavery in those days, while always abusive, were different in important ways from the form of chattel slavery that “Christian” Europeans later introduced into West Africa– most notably because the children of enslaved mothers were not automatically considered to also be “slaves” but were frequently integrated into the enslaver’s family.)

The banner image above is one of thousands of manuscripts on scientific matters produced in Timbuktu under the empire.

Wikipedia tells us this about the Malian empire’s heyday:

Musa Keita became mansa [king] in c. 1312. He made a famous pilgrimage to Mecca from 1324 to 1326. His generous gifts to Mamluk Egypt and his expenditure of gold caused significant inflation in Egypt. Maghan I succeeded his father as mansa in 1337, but was deposed by his uncle Suleyman in 1341. It was during Suleyman’s 19-year reign that Ibn Battuta visited Mali. Suleyman’s death marked the end of Mali’s Golden Age and the beginning of a slow decline.

In 1610 CE, a mansa called Mahmud Keita IV died, and the empire was seemingly split among his three sons. Then this happened: “In 1630, the Bamana of Djenné declared their version of holy war on all Muslim powers in present-day Mali…. [T]he Bamana sacked and burned Niani in 1670.”

Niani was the last place where a traditionally Malian mansa had been ruling. When he left, that was the end of this empire.

Henry Morgan’s profitable sack of Panama City

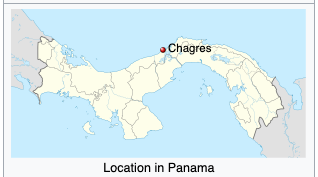

We left the story of the violent, slave-owning English-licensed pirate Henry Morgan two years ago after his punishing raid on Porto Bello, on Panama’s Caribbean coast. This year, he came back to the Panama isthmus, which was a very tempting target for his raids because it was where all the silver mined from Peru and all the takings from Spain’s positions in the Philippines had to be hauled on mule-trains from one coast to the other.

In late 1670, he and the large fleet he commanded reached Chagres, the Caribbean port from which ships were loaded with goods to transport back to Spain. WP tells us that, “Morgan took the town and occupied Fort San Lorenzo, which he garrisoned to protect his line of retreat. On 9 January 1671, with his remaining men, he ascended the Chagres River and headed for Old Panama City, on the Pacific Coast.”

When they got to Panama City there were some intriguing-sounding battles but “The battle was a rout: the Spanish lost between 400 and 500 men, against 15 privateers killed.”

Then this:

Panama’s governor had… placed barrels of gunpowder around the largely wooden buildings. These were detonated by the captain of artillery after Morgan’s victory; the resultant fires lasted until the following day. Only a few stone buildings remained standing afterwards. Much of Panama’s wealth was destroyed in the conflagration, although some had been removed by ships, before the privateers arrived. The privateers spent three weeks in Panama and plundered what they could from the ruins. Morgan’s second-in-command, Captain Edward Collier, supervised the torture of some of the city’s residents…

The value of treasure Morgan collected during his expedition is disputed. Talty writes that the figures range from 140,000 to 400,000 pesos… There were accusations, particularly in Exquemelin’s memoirs, that Morgan left away with the majority of the plunder. He arrived back in Port Royal [Jamaica] on 12 March to a positive welcome from the town’s inhabitants. The following month he made his official report to the governing Council of Jamaica, and received their formal thanks and congratulations.

An English feint to Valdivia?

In late 1669, an English Rear-Admiral called John Narborough led an expedition intended, apparently, to explore the Magellan Straits at the southern tip of South America. Setting out from near London he early on lost contact with the second ship that was supposed to accompany him; but he continued alone. At this stage, England was at peace with Spain. (So what on earth was Henry Morgan doing??)

Narborough reached the southern coast of today’s Argentina in 1670. Once there he visited Port Desire (today’s Puerto Deseado) and “claimed the territory for the Kingdom of England” (!!) He then hopscotched down the the Argentine coast and around some islands at the continent’s tip before coming up the Pacific coast and reaching Corral Bay, a spot heavily fortified by the Spanish in the mouth of the Valdivia River in late December 1670.

WP tells us this happened there:

The expedition established contact with the Spanish garrison whose commanders were highly suspicious of Narborough’s intentions despite England being at peace with Spain. The Spanish demanded and received four English hostages in exchange for allowing Narborough’s ship into the bay. Despite claiming to be in distress and in need of provisions the Spanish refused to give provisions given that the crews seemed to be in healthy condition and Narborough’s true intentions being unclear to them. Narborough then unexpectedly made the decision to leave, and his ship departed Corral Bay on 31 December. The four English hostages and a man known as Carlos Enriques were left behind and ended up in the prisons of Lima where they were subject to lengthy interrogations, as the Spanish struggled to find out the goal of Narborough’s expedition.

Valdivia was the place on the southern coast of Chile that the Dutch had tried to capture a couple of decades earlier. It was also a place where the Indigenous Mapuche had frequently threatened, and on occasion over-run, the heavily armed Spanish settlers. The Spanish being so flummoxed and concerned about Narborough’s presence there did perhaps reduce their ability to send reinforcements up to Panama, though concluding that was Narborough’s goal might be a stretch.

Louis XIV’s diplomatic coup: A secret treaty with Charles II

Louis XIV, with the help of his able First Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, had been stabilizing the large and strategically located country of France for almost a decade by now. (Strategic, because it was between Spain and Netherlands; also, between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic.) Other players in the European theater were concerned about France’s emerging strength, and in 1668, England, Sweden, and the Dutch Republic had joined in a Triple Alliance to try to check France and push it toward making peace with Spain.

All that diplomacy was very complex. What Louis did in 1670, not so much so. He secretly extracted England’s King Charles from the Triple Alliance and got him to agree to convert to Catholicism, simply by the payment of a large chunk of money. He did this in the Secret Treaty of Dover, signed in June 1670. English-WP tells us this about it:

It required that Charles II of England would convert to the Roman Catholic Church at some future date and that he would assist Louis XIV with 60 warships and 4,000 soldiers to help in France’s war of conquest against the Dutch Republic. In exchange, Charles would secretly receive a yearly pension of £230,000, as well as an extra sum of money when Charles informed the English people of his conversion, and France would send 6,000 French troops if there was ever a rebellion against Charles in England.

The same page gives these details about the background:

During 1669, friction among the members of the Triple Alliance convinced Louis that he could induce either England or the Dutch Republic to leave it. Following an unsuccessful attempt to negotiate with the Dutch, Louis was approached by Charles with the offer of an alliance, which was delivered secretly by Charles’ sister. At this stage, the only participants in the talks were Louis XIV of France, Charles II of England, and Charles’s sister Henrietta… Louis was first cousin to Charles (through their grandfather Henry IV of France); Henrietta was also Louis’s sister-in-law through her marriage to his only brother, Phillippe, duc d’Orléans.

Charles’s motives for secretly entering into negotiations with France, while England was still part of the Triple Alliance against France, have been debated among historians. Suggested motives include: a desire to gain the alliance of Europe’s strongest state; to ensure Charles’ political and financial independence from the English parliament; to put England in a position to receive a share of the Spanish Empire if it broke up (the infant Charles II of Spain had no clear heir); to gain the support of English Catholics (and possibly also Protestant dissenters) for the monarchy; or to seek revenge on the Dutch for the English defeat in the Second Anglo-Dutch War, particularly the humiliating Raid on the Medway…

Amazingly, the treaty remained a complete secret until 1771. As WP notes:

Had it been published in Charles II’s lifetime, the results might have been drastic; considering the enormous effect of Titus Oates’s highly unreliable assertions of a Popish Plot, an even greater backlash might have followed had the English public learned that the King actually obliged himself to turn Catholic and that he was willing to rely on French troops to impose that conversion on his own subjects.

Soon after the two monarchs had concluded the secret treaty, they sent representatives to negotiate and sign a “cover” treaty. Charles sent the Duke of Buckingham to do this. WP notes that the duke was amazed by how smoothly those negotiations went (!) and adds:

This treaty closely followed the secret treaty just concluded, but the clause by which King Charles was to declare himself a Roman Catholic as soon as the affairs of his kingdom permitted did not appear; neither, therefore, did the stipulation that the attack on the Netherlands would follow his declaration. This treaty was signed by all five members of the Cabal Ministry on 21 December 1670 and was made known to the public. However King Charles and the French knew it was a meaningless fake.

Meantime, the Secret Treaty fairly speedily had some real consequences. On April 6, 1672, Louis declared war on the Dutch. Charles followed suit the next day. France meanwhile paid Sweden to remain neutral and promised military support to Sweden if it should be threatened by by Brandenburg-Prussia. Louis had completed the diplomatic (and military) encirclement of the Dutch UPs.

Also, in 1672, Charles issued a “Declaration of Indulgence” that suspended the laws that limited religious activities by non-C-of-E Protestants and relaxed but did not suspend the laws limiting Catholic activities. (Those provisions were contested and speedily reversed by an angry parliament.)

It is not clear if he secretly converted to Catholicism at that time or later in his life, though his page on WP says he “was received into the Catholic church” on his deathbed, in 1685.

Anyway, the WP page on the Secret Treaty makes this concluding judgment on it:

Overall, Charles made a serious error of judgement in signing the Treaty of Dover. Firstly, he underestimated the political skill of Louis, who involved him in a war of little advantage to England but one that was greatly desired by Louis to further his objectives. Secondly, he also underestimated Dutch resilience…

Indeed.

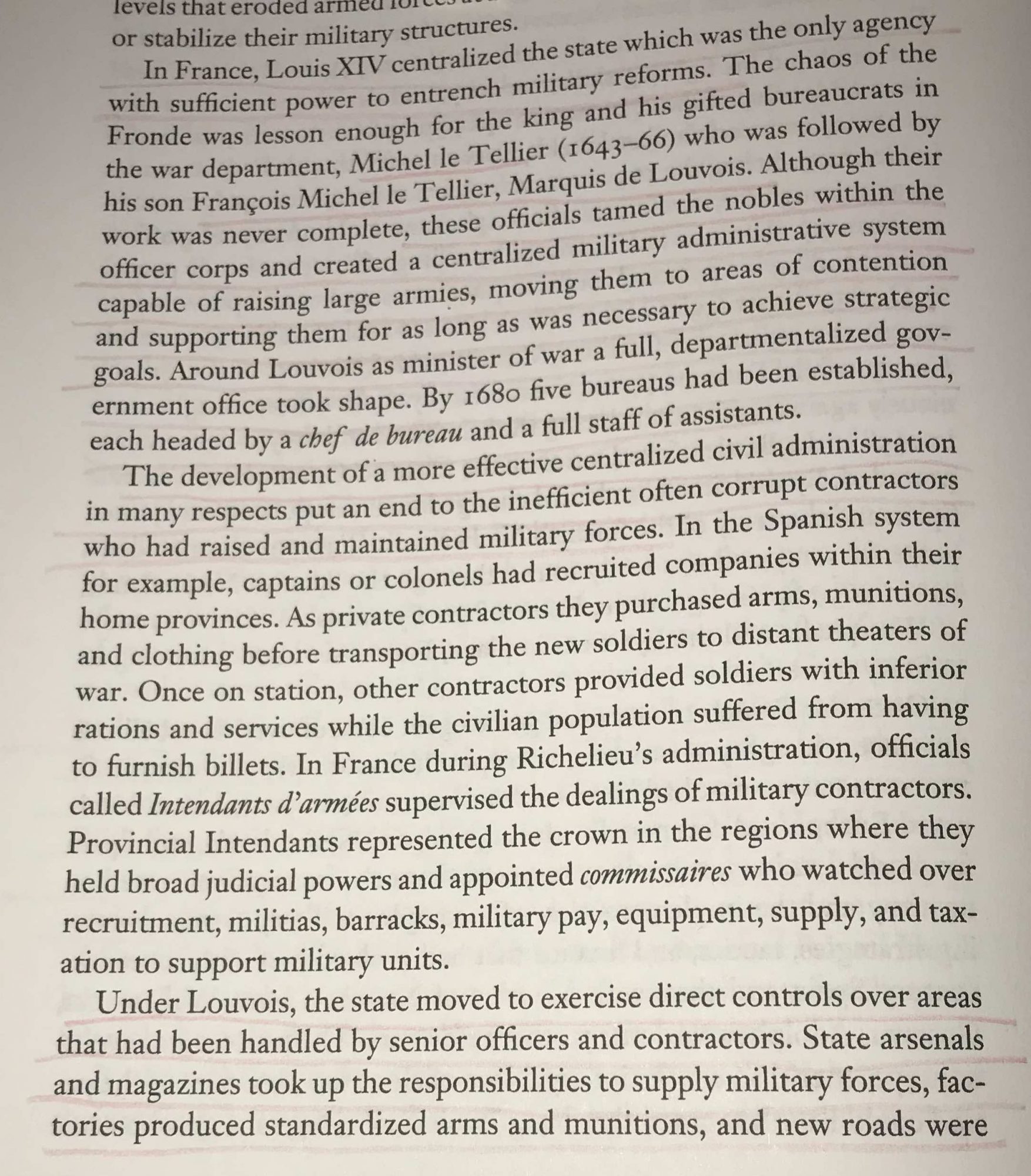

France’s military professionalizes

In their World History of Warfare, historians Christon I. Archer and his three co-authors note (p.303) that “In many respects, France’s rise to power [at the end of the 17th century] rested on its army and the implementation of a complex military system involving strategies, tactics, and finance… ” They note, too, that “With a large population of over twenty million and the economic potential to build and maintain powerful armies and fleets, France possessed all of the potential resources for military power.” (ibid.)

In the middle of the century, France had been plagued by a series of internal conflicts collectively called the Fronde. But by 1653, the still-young Louis’s regent– his mother– and her chief adviser Cardinal Mazarin had brought those to an end. In 1659, France’s conflicts with Spain in the Spanish Netherlands and the Pyrenees were ended. In 1661, Mazarin died and the 23-year-old Louis assumed full control, appointing Mazarin’s protegee Jean-Baptiste Colbert as his first minister and inheriting from Mazarin the man who had been his War Minister since 1643, Michel Le Tellier.

Archer et al. write that after Louis assumed full powers in 1661 he “would construct a military machine that rapidly became the wonder of the age.” (p.304) Much of this military modernization was led by Le Tellier’s son, the Marquis of Louvois, who succeeded him as Secretary of State for War in 1662, aged only 21.

One key to Louvois’s military modernization was the centralization of as many as possible of the functions of the French state, which was, they write, “the only agency with sufficient power to entrench military reforms.”

They continue thus:

They also note (p.305) that the reforms to the military in that era included these steps:

- Regular inspections of accounts, inventories, and manpower at all levels.

- Reform of the seniority system.

- Building of barracks and confinement of the military to them.

- Building a military-hospital and veteran-care system.

- Institution of regular drilling of infantry– under an inspector-general of infantry, Jean Martinet, whose name became eponymous for tough discipline.

- Frequent review and updating of military techniques, including introduction of the flintlock which meant the unwieldy “arquebus” stands for muskets were no longer needed.

In these decades of the late 17th century the French military could also draw on the talents of the gifted military engineer and strategic Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban who was responsible not only for designing and building a new series of innovatively-appointed forts along many parts of France’s borders but also for deciding where they should be positioned for maximum effect, how they should be supplied, and so on. He also had great insights into how to breach other countries’ forts and defined the strategy for many of France’s late-17th century wars. WP tells us that

In the course of his career, Vauban supervised or designed the building of more than 300 separate fortifications, and by his own estimate, supervised more than 40 sieges from 1653 to 1697.

In 1703, Vauban would be appointed Maréchal de France, a step that ended his active-duty military career. WP tells us what he did then:

With more leisure time, Vauban developed a broader view of his role. His fortifications were designed for mutual support, so they required connecting roads, bridges and canals; garrisons needed to be fed, so he prepared maps showing the location of forges, forests, and farms. Since these had to be paid for, he developed an interest in tax policy, and in 1707 published La Dîme royale, documenting the economic misery of the lower classes. His solution was a flat 10% tax on all agricultural and industrial output, and eliminating the exemptions which meant most of the nobility and clergy paid nothing. Although confiscated and destroyed by Royal decree, the use of statistics to support his arguments … establishes him as a founder of modern economics, and precursor of the Enlightenment’s socially concerned intellectuals.

WP’s final assessment of his legacy was this:

Vauban’s offensive tactics remained relevant for centuries; his principles were clearly identifiable in those used by the Việt Minh at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. His defensive fortifications dated far more quickly, partly due to the enormous investment required; Vauban himself estimated that in 1678, 1694 and 1705, between 40 and 45% of the French army was assigned to garrison duty.

But meanwhile, just to bring this back to the realm of empire-building and imperialism, I note that Archer et al. wrote this:

Well, I haven’t seen any evidence of effective French empire-building activity yet but I know it is shortly to come. One thing that does interest me is that, while for England and the Netherlands the creation/consolidation of a “national” identity and institutions of nationhood seemed to flow largely from those countries’ respective maritime projects overseas. And maybe for Portugal, too. But for Spain, and now for France, it is possible to conjecture that territorial consolidation at home was the precursor for empire-building overseas.