Here are the news items for 1645 CE:

- Mapuche-Huilliches inflict defeat on Spanish in south of today’s Chile

- Portuguese oust Dutch from Brazil

- Cromwell pivots to the Caribbean

- He also has problems with new parliament in London.

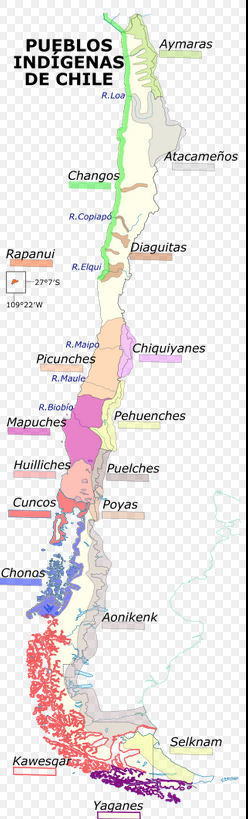

Mapuche-Huilliches inflict defeat on Spanish in south of today’s Chile

I’m afraid I can’t get any more details about this event except a short squib in Wikipedia’s annual listing for 1654:

- January 11 – A Spanish army is defeated by local Mapuche-Huilliches as it tries to cross Bueno River in Southern Chile.[1]

However, I always love hearing news of the resilience of the Mapuches, who have actually kept up their resistance to European colonialism until today. See this great little news item from Al-Jazeera about current events and possibilities in Mapuche-land.

This WP page on the Huilliche people tells us:

The Huilliche [wi.ˈʝi.tʃe], Huiliche or Huilliche-Mapuche are the southern partiality of the Mapuche macroethnic group of Chile. The Huilliche are the principal indigenous population of Chile from Toltén River to Chiloé Archipelago. According to Ricardo E. Latcham the term Huilliche started to be used in Spanish after the second founding of Valdivia in 1645, adopting the usage of the Mapuches of Araucanía for the southern Mapuche tribes. Huilliche means ‘southerners’ (Mapudungun willi ‘south’ and che ‘people’.)

… Most Huilliche speak Spanish, but some, especially older adults, speak the Huilliche language.

The Huilliche calls the territory between Bueno River and Reloncaví Sound Futahuillimapu, meaning “great land of the south.”

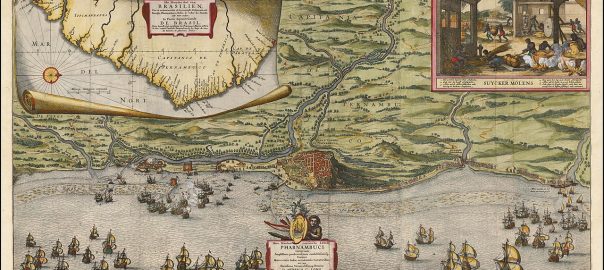

Portuguese oust Dutch from Brazil (having already ousted them from Angola)

As we already know, in 1645 the Dutch, who had held a significant portion of land around Recife in eastern Brazil since 1630, confronted a serious uprising from the many Portuguese plantation owners who had been there for many decades prior. By 1646, the Dutch West India Company (GWC) only controlled Recife itself and three other toeholds along the Brazilian coast.

Okay, so meantime something else very relevant had been happening that I had completely failed to notice or record. In 1641, Johan Maurits, the Dutch Governor of Recife had sent an expedition across the Atlantic that had captured the Angolan capital of Luanda from the Portuguese. This page on WP gives us these details:

The Dutch were able to easily capture Luanda in August as the Portuguese forces were occupied inland in a campaign against the Kingdom of Kongo. The two countries fought to a stalemate over Angola, until in 1648 the governor of Rio de Janeiro and Angola, Salvador de Sá, reached Luanda and finding the city defended by 1200 Dutch troops, besieged them and regained it for Portugal exactly seven years after its loss…

He also sent a fleet which recaptured the archipelago of São Tomé e Príncipe from the Dutch, who left behind their artillery.

[The Portuguese recapture of Angola] was a decisive Dutch defeat since Dutch Brazil couldn’t survive without the slaves from Angola. The end of Dutch presence in South America (with the exception of the Guiana) meant not only the bankruptcy of the [GWC], but also the end of most of the West Dutch empire.

By the way, remember Queen Nzingha Mbande who reigned over two kingdoms in northern Angola? She had allied with the Dutch during their time there, but when the Portuguese ousted the Dutch she was able to escape into the Angolan interior.

… So, back to Dutch Brazil. In 1652, the Portuguese had sent an expeditionary force to oust the Dutch from their last toeholds there. After fierce fighting and a two-year siege, the Portuguese finally took Recife on 28 January 1654. WP tells us this about the aftermath:

In the aftermath of the Dutch occupation, Portuguese settled scores with Amerindians who had supported the Dutch. There were tensions between Portuguese who had fled the area under occupation and those who had lived under Dutch occupation. The returnees attempted to litigate so as to regain the properties they had abandoned, which in this sugar-producing area included sugar mills and other buildings, as well as cane fields. The litigation dragged on for years.

The conflict in Brazil’s northeast had severe economic consequences. Both sides had practiced a scorched earth policy that disrupted sugar production, and the war had diverted Portuguese funds from being invested in the colonial economy. After the war, Portuguese authorities were forced to spend their tax revenues on rebuilding Recife. The sugar industry in Pernambuco never fully recovered from the Dutch occupation, being surpassed by sugar production in Bahia.

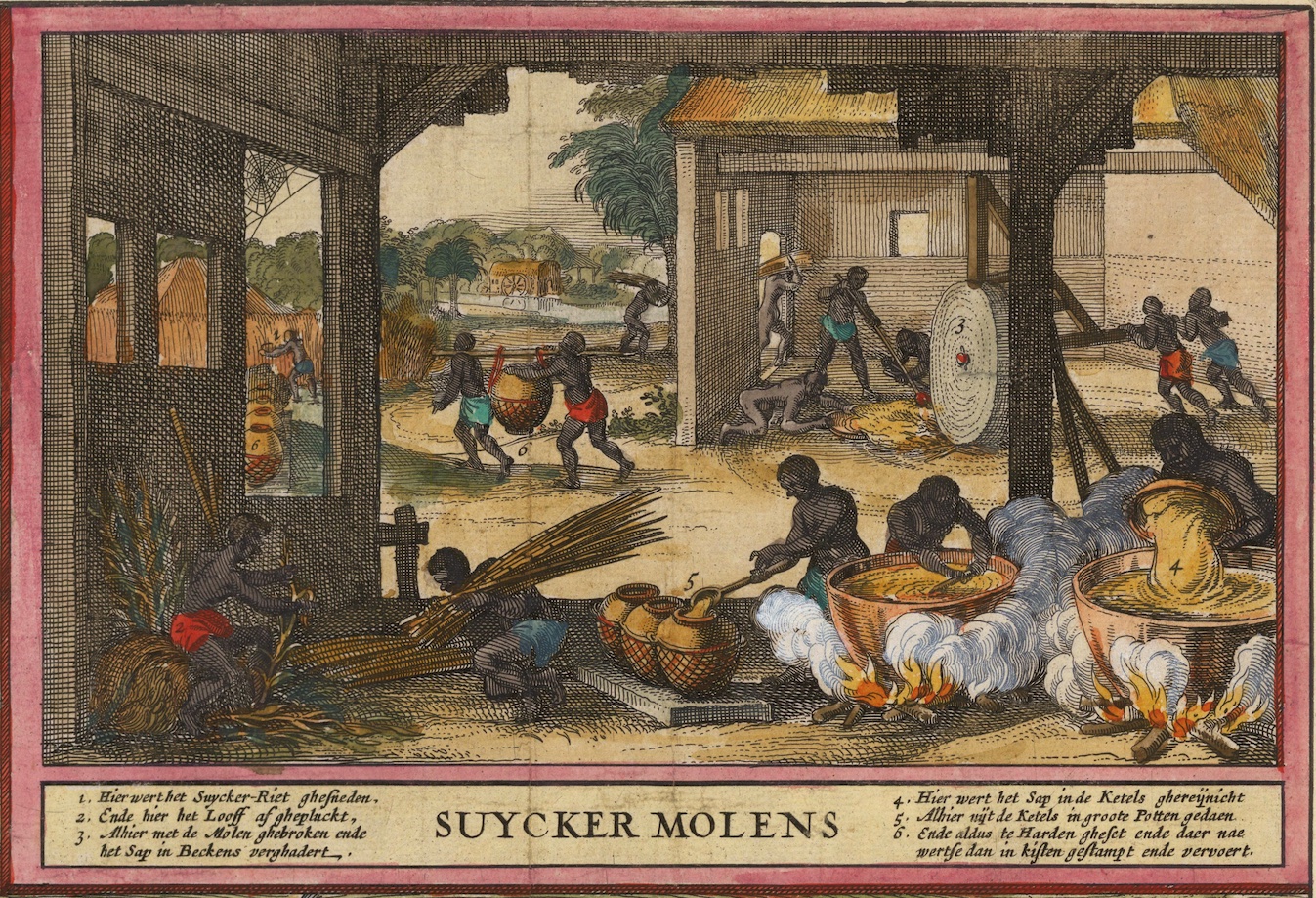

Meanwhile, the British, French, and Dutch Caribbean had become a major competitor to Brazilian sugar due to rising sugar prices in the 1630s and 1640s. After the WIC evacuated Pernambuco, the Dutch brought their expertise and capital to the Caribbean instead. In the 1630s, Brazil provided 80% of the sugar sold in London, while it only provided 10% by 1690. The Portuguese colony of Brazil did not recover economically until the discovery of gold in southern Brazil during the 18th century.

Cromwell pivots to the Caribbean

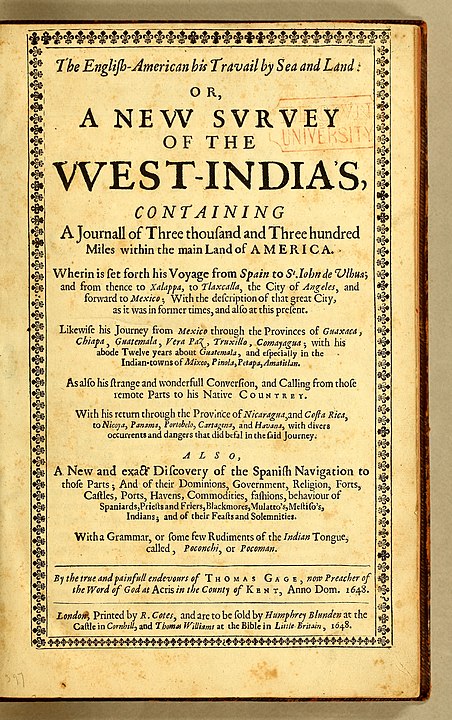

By 1654 it had become clear not only to the Dutch and Portuguese but also to Oliver Cromwell and members of England’s rapidly expanding class of merchant-adventurers and investors that sugar plantations were the latest, most profitable project for aspiring colonial powers– and that the Caribbean would likely be the best place to establish these. (See the cover of the 1648 pamphlet shown at right– one of many extolling the riches of the Americas to English readers in those years.)

A number of other factors drew Cromwell’s attention to the area. First, much of the terrain in the Caribbean, including its largest islands and the coasts of Venezuela and Central America, was controlled by the Spanish, part of an empire that now seemed to be weakening everywhere. Second, the Puritans and other uber-Protestants around Cromwell had a lot of antagonism to Catholic Spain. Oh, and in April 1654, he had concluded the Treaty of Westminster with the Dutch, bringing an end to that stalemated inter-imperial war and freeing up his military for other encounters.

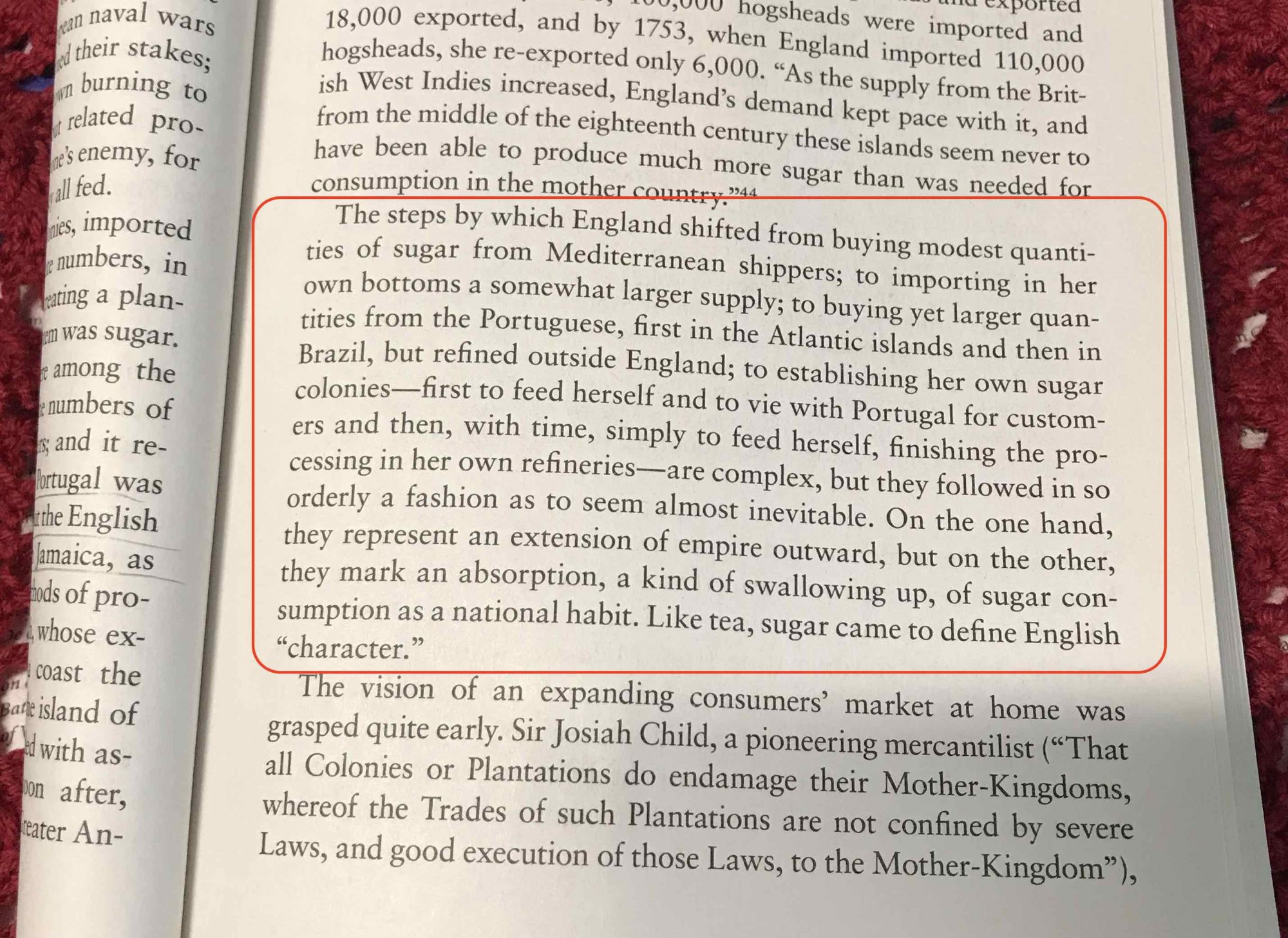

But really, in the mid-1600s, sugar was the big prize. Sidney Mintz summarized what was happening excellently, on page 39 of his excellent book Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History.

Thus, during 1654, Cromwell assigned some of his best military planners to devise a plan to oust Spain from the Caribbean. This was called the “Western Design”. WP tells us this about it:

A committee under Cromwell’s brother-in-law General John Disbrowe supervised logistics; with the end of the Dutch war, the New Model Army was being reduced and the expedition provided an opportunity to employ surplus troops. However, relatively few were willing to serve in an area notorious for sickness and disease; of the 2,500 troops who sailed from England, fewer than half were experienced, the rest untrained recruits. They were led by Robert Venables, a veteran of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms recently returned from four years of often brutal campaigning in Ireland; although well regarded by Cromwell, his complaints about the poor condition of these troops were ignored.

Venables shared command with Admiral William Penn, who had a fleet of eighteen warships and twenty transport vessels; he too was an experienced and competent officer, but joint command resulted in friction and mutual hostility between the two men…

The fleet left Portsmouth at the end of December 1654 and arrived in Barbados a month later. Between three and four thousand additional troops were raised from volunteers among the indentured servants and freemen in the colonies of Barbados, Montserrat, Nevis and St Kitts to make the numbers of the five original regiments up to 1,000 men each and to form a sixth regiment. The troop numbers looked impressive, but they were untrained and badly disciplined. Furthermore, supplies were running low and the joint commanders Penn and Venables were arguing with one another. Morale among the soldiers sank lower still when the civilian commissioners stipulated that they were not to plunder the Spanish colonies they were about to attack but rather to preserve them intact for subsequent English colonisation…

You’ll have to wait till next year to see how the expedition fared.

Cromwell’s problems with his new parliament in London

The “Instrument of Government” that Maj.-Gen. John Lambert had drawn up in 1653, to be England’s first written Constitution, had instituted several good reforms, including with the redistribution of many parliamentary seats from the “Rotten Boroughs” to some of the new urban areas developing in the country.

Cromwell had been sworn in as “Lord Protector”of England, Scotland, and Ireland in December 1653, in a ceremony in which, WP tells us,

he wore plain black clothing, rather than any monarchical regalia. However, … it soon became the norm for others to address him as “Your Highness”. As Protector, he had the power to call and dissolve parliaments but was obliged under the Instrument to seek the majority vote of a Council of State. Nevertheless, Cromwell’s power was buttressed by his continuing popularity among the army. As the Lord Protector he was paid £100,000 a year.

In September 1654 he summoned his first parliament. WP tells us how it went:

It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the House.

During the first nine months of the Protectorate, Cromwell with the aid of the Council of State, had drawn up a list of 84 bills to present to Parliament for ratification. But the members of Parliament had their own and their constituents’ interests to promote and in the end not enough of them would agree to work with Cromwell, or to sign a declaration of their acceptance of the Instrument of Government, to make the constitutional arrangements in the Instrument of Government work. Cromwell dissolved the Parliament as soon as it was allowed under the terms of the Instrument of Government, having failed to get any of the 84 bills passed.

Oops.