The three development of geo-historical significance in 1651 CE were as follows:

- Conquistadors in Chile negotiate deal with Mapuche indigenes but a naval incident threatens that.

- Cromwell lures Charles II’s Scottish army into a deadly trap far south of the border.

- London’s Parliament gets serious about seapower and its link to imperial trade.

I will address each of those in order below. First, the year’s Small News.

Small News of 1651

1. T. Hobbes publishes ‘Leviathan’, ducks ensuing uproar

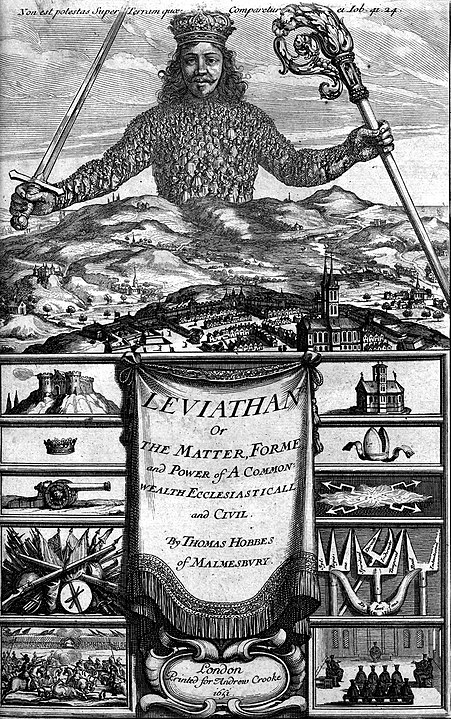

We last met the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes in 1647, when he was in Paris tutoring then-Prince Charles (II) in math. In mid-1651, he published the work for which he is best known, Leviathan, in which he argued that since “man” (no mention of women) was by nature selfish, individualistic, and violent, that meant that a strong central authority is required to curb those instincts. It had a famous title-page, as shown. WP tells us that:

The first effect of its publication was to sever his link with the exiled royalists, who might well have killed him. The secularist spirit of his book greatly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics. Hobbes appealed to the revolutionary English government for protection and fled back to London in winter 1651. After his submission to the Council of State, he was allowed to subside into private life in Fetter Lane.

2. Franco-Spanish war continues, including in Mediterranean

Spain, you might remember, had been battling its Catalan separatists for many years, and the Catalans had received good support from France. Spain at that time controlled Sicily, and in early 1651 tasked its Viceroy in Sicily, who confusingly was called John of Austria, to sail over to the Catalan capital, Barcelona, and sort things out. On the way over, near Ibiza, he spotted a beautiful French ship called the Lion Couronné, which he decided to capture. He did that in a sea-battle in which around a hundred were killed on each side.

3. Ottoman empire’s power “Queen Mother” gets strangled

We’ve met Kösem Sultan, the powerful valide sultan (“Queen Mother”) in Istanbul several times before. She’d been born, probably Greek, in 1589 and brought as a sex-slave to the Ottoman court where she achieved considerable power by becoming haseki sultan (favorite consort) of Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603–1617), and valide sultan as mother of Murad IV (r. 1623–1640) and Ibrahim (r. 1640–1648), and grandmother of Mehmed IV. Mehmed IV was enthroned in 1648 when he was six and was still on the throne in 1651… During all those transitions she had been a powerful behind-the-scenes figure and during Mehmed IV’s reign she was determined to continue to wield power as regent.

WP takes up the story:

It was Mehmed IV’s mother, Turhan, who proved to be Kösem’s nemesis. When she was about 12 years old, Turhan was sent to the Topkapı Palace as a gift from the khan of Crimea to Kösem Sultan. It was probably Kösem Sultan who gave Turhan to Ibrahim as a concubine. Turhan turned out to be too ambitious a woman to lose such a high position without a fight. In her struggle to become valide sultan, Turhan was supported by the chief black eunuch in her household and the grand vizier, while Kösem was supported by the Janissary Corps. Although Kösem’s position as valide was seen as the best for the government, the people resented the influence of the Janissaries on the government.

In this power struggle, Kösem planned to dethrone Mehmed and replace him with another young grandson. According to one historian, this switching had more to do with replacing an ambitious daughter-in-law with one who was more easily controlled. The plan was unsuccessful as it was reported to Turhan by Meleki Hatun, one of Kösem’s slaves, that Kösem was said to be plotting Mehmed’s removal and replacement by another grandson with a more pliant mother. Whether Turhan sanctioned it or not, Kösem Sultan was murdered three years after becoming regent for her young grandson. It is rumoured that Turhan ordered Kösem’s assassination. Furthermore, some have speculated that Kösem was strangled with a curtain by the chief black eunuch of the harem, Tall Suleiman. The Ottoman renegade Bobovi, relying on an informant in the harem, states that Kösem was strangled with her own hair.

Enough with the Real Housewives (or mothers-in-law) of the Topkapi Palace! Let’s get to some real news.

(The banner image above is part of an engraving of the strangling of Kösem Sultan.)

Conquistadors in Chile negotiate deal with Mapuche indigenes but a naval incident threatens that.

I have become intrigued by the story of the Mapuche, a confederation of Indigenous peoples who straddle the border of today’s Chile and Argentina and who were able to resist the Spanish conquistadores for more than two centuries. In January 1651, representatives of various Mapuche groups held a negotiations gathering (“Parliament”) at Boroa with a Spanish delegation headed by the Spanish Governor of Chile, Antonio Acuña Cabrera, who had reportedly traveled there incognito from a fortress in the north accompanied only by six men.

English-WP tells us this about the treaty that resulted:

The terms of the treaty were detrimental to the Mapuche, almost everything agreed then was in favour of the Spanish, including a prohibition for the Mapuche to wear weapons unless the Spanish ask them to do so. Mapuches were also to help the Spanish build forts and allow them free passage through their lands.

However, just a couple of months later an event occurred that put the treaty at risk. Do you remember Valdivia? It was the long-ago Spanish coastal outpost that was one of the “Seven Cities” in southern Chile that the Spanish had to withdraw from as a result of an earlier Mapuche uprising, and the spot where a few years ago the Dutch had tried–but failed– to establish their own Chile-coast beach-head. After rebuffing the Dutch attempt, the Spanish authorities decided to fortify Valdivia. But they still could not access it by land because of Mapuche control of all land trails. So they had to periodically resupply it by sea.

In March 1651, this happened:

The Spanish ship San José was sailing to Valdivia was pushed by storms on March 26 onto coasts inhabited by the Cuncos, a southern Mapuche tribe. There, the ship ran aground and while most of the crew managed to survive the wreck, nearby Cuncos killed them and took possession of the valuable cargo. Among the cargo was the payment to the garrison of Valdivia.

… Governor Acuña Cabrera was temporarily dissuaded to send a punitive expedition from Boroa by Jesuit fathers Diego de Rosales and Juan de Moscoso who argued that the murders were committed by a few Indians and warned the governor that renewing warfare would evaporate gains obtained at Boroa… {But] punitive expeditions were finally sent against the Cunco, one from Valdivia and one from Carelmapu.

Governor of Valdivia Diego González Montero advanced south with his forces but soon found that tribes he expected to join him as allies were indifferent and even misled him with false rumors. His troops ran out of supplies and had to return to Valdivia. While González Montero was away coastal Huilliches killed twelve Spanish and sending their heads to other Mapuche groups of southern Chile “as if they wanted to create a grand uprising” according to historian Diego Barros Arana… The expedition from Carelmapu led by Captain Ignacio Carrera Yturgoyen penetrated north to the vicinity of the ruins of Osorno where they were approached by Huilliches who handed over three “caciques”, allegedly responsible for the murders. The Spanish and local Huilliches exchanged words telling each other of the benefits of peace. Then, the Spanish of Carelmapu executed the three, hanged them in hooks as a warning, and returned south. Spanish soldiers in Concepción, the “military capital” of Chile, were dissatisfied with the results. Barros Arana consider some may have pushed for renewed war for personal benefit.

What a shocking thought!

Cromwell lures Charles II’s Scottish army into a deadly trap far south of the border.

In January 1651, the young Charles, still only 20, was crowned King of Scotland at Scone Abbey in Perth, Scotland. He then gathered his Scottish advisors around him to plan how to defeat Cromwell’s Parliamentarian ‘New Model Army’ (NMA) and thus regain the English throne that he also considered rightly his.

Cromwell was still in Scotland with the fighting units that had inflicted a defeat on Charles in Dunbar the year before. English-WP tells us what happened next:

The commander of the Scots, David Leslie, supported the plan of fighting in Scotland, where royal support was strongest. Charles, however, insisted on making war in England. He calculated that Cromwell’s campaign north of the River Forth would allow the main Scottish Royalist army which was south of the Forth to steal the march on the Roundhead New Model Army in a race to London. He hoped to rally not merely the old faithful Royalists, but also the overwhelming numerical strength of the English Presbyterians to his standard. He calculated that his alliance with the Scottish Presbyterian Covenanters and his signing of the Solemn League and Covenant would encourage English Presbyterians to support him…

Why on earth would David Leslie, then a seasoned military man some 50 years of age, have listened to the stripling Charles? Maybe that’s what being a “Royalist” means? …So at some point in the summer of 1651 they set out to the south. The WP page on the battle that was eventually joined at Worcester, far south of the border, tells us this:

The Royalist army was kept well in hand, no excesses were allowed, and in a week the Royalists covered 150 miles…

But the Royalists were mistaken in supposing that the enemy was unaware. Everything had been foreseen both by Cromwell and by the Council of State in Westminster. The latter had called out the greater part of the militia on 7 August. Lieutenant-General Charles Fleetwood began to draw together the midland contingents at Banbury. The London trained-bands turned out for field service no fewer than 14,000 strong. Every suspected Royalist was closely watched, and the magazines of arms in the country-houses of the gentry were for the most part removed into the strong places. On his part Cromwell had quietly made his preparations. Perth passed into his hands on 2 August and he brought back his army to Leith by 5 August. Thence he dispatched Lieutenant-General John Lambert with a cavalry corps to harass the invaders. Major-General Thomas Harrison was already at Newcastle picking the best of the county mounted-troops to add to his own regulars. On 9 August, Charles was at Kendal, Lambert hovering in his rear, and Harrison marching swiftly to bar his way at the Mersey. Thomas Fairfax emerged for a moment from his retirement to organize the Yorkshire levies, and the best of these as well as of the Lancashire, Cheshire and Staffordshire militias were directed upon Warrington, which Harrison reached on 15 August, a few hours in front of Charles’s advanced guard. Lambert too, slipping round the left flank of the enemy, joined Harrison, and the English fell back (16 August), slowly and without letting themselves be drawn into a fight, along the London road.

“The English” there meant the Parliament side, since Charles’s army was all Scottish; the many English Presbyterians and Royalists he had confidently expected would join him along the way never materialized. As a result, the further south into England it traveled, the more it was seen as an army of foreign invaders.

Cromwell had left his least efficient regiments in Scotland and led a large contingent southwards, to the east of the Pennines, expecting to meet Charles’s army somewhere near Coventry as they headed southeast to take London. But Charles did not do that. He decided instead to head for the upper reaches of the Severn Valley, judging that area to have a lot of Royalist sympathizers. He arrived at Worcester, a strategic location just north of the confluence of the Severn and Teme Rivers, on August 22. There, he “spent five days in resting the troops, preparing for further operations, and gathering and arming the few recruits who came in.”

That gave Cromwell and his fellow NMA generals time to plan their assault. Time had basically been on their side ever since Charles got any distance south of the border, and after Cromwell arrived near Worcester he took a couple of days more of it to construct pontoon bridges over both rivers that would supplement the existing bridges and give his units more flexibility for approach and maneuver.

Battle was joined on September 3. There was some fierce fighting, but the Parliamentary forces were superior in number (28,000 to 16,000), well trained, and fighting on terrain familiar to many of them. By the end of the day the Royalists were defeated. They had suffered 3,000 killed and 10,000 captured. The NMA suffered 700 killed.

After the Battle of Worcester, there was no threat of a Royalist Restoration in England (or Scotland, or Ireland) that was imminent or even on the horizon. Cromwell could set about consolidating his power– at home, and overseas.

Charles managed to escape in disguise; after traveling as a fugitive around southwestern England for some weeks he was finally able to escape to safety in France.

Of the 10,000 Royalists taken prisoner, WP tells us this:

The Earl of Derby was executed, while the other English prisoners were conscripted into the New Model Army and sent to Ireland. Around 8,000 Scottish prisoners were deported to New England, Bermuda, and the West Indies to work for landowners as indentured labourers, or else to work on fen drainage [in eastern England]. Around 1,200 “Scotch prisoners” were taken to London; many died from disease and starvation at Tothill Fields and other makeshift prison camps.

London’s Parliament gets serious about seapower and its link to imperial trade

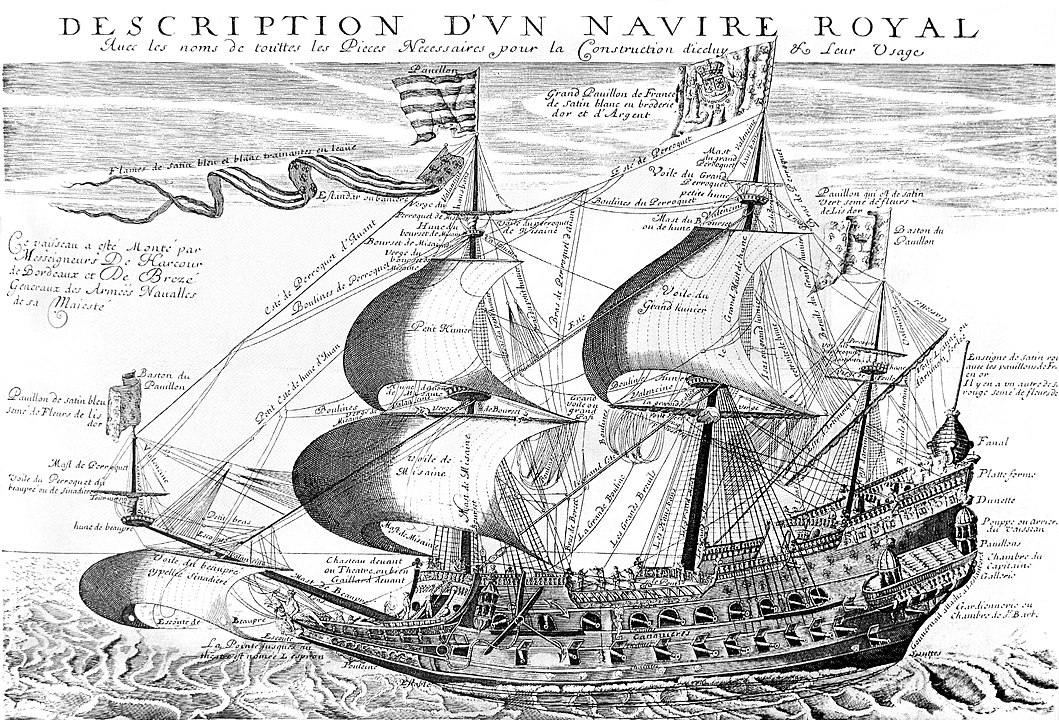

The British Isles– even, all of them together!– are, as an earlier Ottoman Sultan had remarked, just a tiny speck of land and until very recently totally reliant on shipping to transport people or goods to any other parts of Europe or the world. Oliver Cromwell, in 1651 still continuing his rise toward total power, was a land-fighting expert, but like any English military thinker he was keenly aware of the importance of seapower. In 1649, as we have seen, he appointed Robert Blake to head and to modernize the English navy. In 1651, he and the rest of the Parliament turned to the econo-strategic impact of merchant navigation to the English economy: they passed the first of a series of Navigation Acts that would define the nature of the English (later British) Empire for the next two centuries.

English-WP gives us this important background to Parliament’s passage of the 1651 Navigation Act:

Passage of the act was a reaction to the failure of the English diplomatic mission (led by Oliver St John and Walter Strickland) to The Hague seeking a political union of the Commonwealth with the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands, after the States of Holland had made some cautious overtures to Cromwell to counter the monarchical aspirations of stadtholderWilliam II of Orange. The stadtholder had suddenly died, however, and the States [of Holland] were now embarrassed by Cromwell taking the idea too seriously. The English proposed the joint conquest of all remaining Spanish and Portuguese possessions. England would take America and the Dutch would take Africa and Asia. But the Dutch had just ended their war with Spain and already taken over most Portuguese colonies in Asia, so they saw little advantage in this grandiose scheme and proposed a free trade agreement as an alternative to a full political union. This again was unacceptable to the British, who would be unable to compete on such a level playing field, and was seen by them as a deliberate affront.

As for the content of the Act, that same page on WP describes it thus:

It authorized the Commonwealth to regulate England’s international trade, as well as the trade with its colonies. It reinforced long-standing principles of national policy that English trade and fisheries should be carried in English vessels.

The Act banned foreign ships from transporting goods from Asia, Africa or America to England or its colonies; only ships with an English owner, master and a majority English crew would be accepted. It allowed European ships to import their own products, but banned foreign ships from transporting goods to England from a third country elsewhere in the European sphere. The Act also prohibited the import and export of salted fish in foreign ships, and penalized foreign ships carrying fish and wares between English posts. Breaking the terms of the act would result in the forfeiture of the ship and its cargo. These rules specifically targeted the Dutch, who controlled much of Europe’s international trade and even much of England’s coastal shipping. It excluded the Dutch from essentially all direct trade with England, as the Dutch economy was competitive with, not complementary to the English, and the two countries, therefore, exchanged few commodities. This Anglo-Dutch trade, however, constituted only a small fraction of total Dutch trade flows.

The full text of the Act spelled out in its first paragraph that most of its provisions would go into effect on December 1, 1651. It also spelled out that any infraction of its terms would be subject to:

the penalty of the forfeiture and loss of all the goods that shall be imported contrary to this act; as also of the ship (with all her tackle, guns and apparel) in which the said goods or commodities shall be so brought in and imported; the one moiety [half] to the use of the Commonwealth, and the other moiety to the use and behoof of any person or persons who shall seize the goods or commodities, and shall prosecute the same in any court of record within this Commonwealth.

This provision was like a starting gun for the many experienced privateers (state-licensed pirate ships) that lurked around England’s coasts. This other page on WP tells us this:

In 1651, 140 Dutch merchantmen were seized on the open seas. During January 1652 alone, another 30 Dutch ships were captured at sea and taken to English ports. Protests to England by the States General of the United Provinces were of no avail: the English Parliament showed no inclination toward curbing these seizures of Dutch shipping.

Stay tuned…