Yes, 1640 CE was a big year for inter-imperial change and there will be more to come. So today I will try to sort out the two big threads of 1641, which are: (1) The Portuguese-Spanish-Dutch thread, and (2) The English-Scottish-Irish thread.

Fall-out from Portugal’s secession from Spain

It was on December 1, 1640 that the Portuguese Cortes announced its secession from the Iberian Union and its acclamation of John IV as king of newly independent Portugal. The historian Stanley G. Payne wrote (Payne, 1973, pp.314-15):

Portuguese separation was a response to the crisis of the Spanish empire, the frustration of its leadership, the burden of its defense, and above all, the decline of its economy. The Spanish crown could no longer offer Portugal either the protection or the opportunities of a generation or two earlier. Rather, it would involve Portugal further in the suffering of its wars and their heavy cost. The Catalan revolt provided Portuguese leaders with a model which they were able to imitate more successfully. Unlike the Spanish trade in the Atlantic, that of the Portuguese was in a phase of moderate expansion and helped to provide Portugal with an economic base for independence. After 1640, the Spanish crown was in no position to build a new army for the subjugation of Portugal.

This gave Portugal the opportunity to reclaim its own foreign policy and the management of its own empire. Before the end of 1640, John IV had sent ambassadors to France, England, and the Dutch Republic; and on June 12, 1641, the ambassador in The Hague signed a ten-year truce with the Dutch States-General called the “Treaty of Offensive and Defensive Alliance.” The Dutch had paved the way for the Portuguese back in 1581, when they undertook their own secession from the Habsburg Empire that Spain led.

If the Portuguese hoped for some sympathy from the Dutch (which I doubt), they would have been sorely disappointed. The Dutch had for several decades now been eating very aggressively away at many of the trading/raiding centers that Portugal had long maintained in the East Indies, Ceylon, and other parts of the Indian Ocean littoral, as well as at Portugal’s positions in Brazil. Indeed, in January 1641 an armed fleet of the Dutch VOC captured the key Portuguese fortress in Malacca (in today’s Malaysia.) English-WP tells us that, “The Dutch ruled Malacca from 1641 to 1798 but they were not interested in developing it as a trading centre, placing greater importance on Batavia (Jakarta) and Java as their administrative centre.”

There is little evidence that Dutch behavior towards Portugal’s transoceanic colonial holdings changed much after the conclusion of the 1641 truce. (The banner image above is a 1750 view of Malacca from the Strait.)

Closer to home, however, 1641 did bring some evidence of an intriguing joint project. This WP page tells us what happened:

In 1641… the Portuguese government, with Dutch and French help, prepared to start the offensive against Spain at sea. Dom António Telles da Silva, who had fought the Dutch in India, was designated commander of a squadron of 16 [Portuguese] ships, which along with another 30 of the Dutch Republic… was entrusted with the mission to capture and hold the Spanish towns of Cádiz and Sanlúcar [not far from Cádiz on Spain’s southern coast.] The attempts failed thanks to the fortuitous encounter that they had with 5 [pro-Spanish Netherlanders] under Judocus Peeters.

Peeters managed to reach Cádiz and alerted the authorities there. The commanders of the attacking coalition realized they had lost the element of surprise and went to regroup in Lisbon. At that point, the Dutch fleet set out to to try to capture the Spanish Treasure Fleet that they hoped would be coming in some time soon, instead of proceeding with the original plan. It is not clear what the Portuguese and French fleets did.

The Spanish naval authorities in Cádiz immediately organized a naval expedition to go and confront the expected attackers. But instead, the Spanish fleet sighted the Dutch fleet at some point off Cape St. Vincent, which is at the extreme southwest tip of Portugal, and decided to attack it there and then. English-WP describes the outcome of this battle as a “Spanish victory”. But it also says the Spanish side lost 1,100 men killed while the Dutch side lost “100-200”. Each side lost two ships; and after the sea-battle each of the two fleets retreated and went back to its home base. So it seems more like a stand-off to me?

Anyway, the anti-Spanish coalition the Portuguese had hoped to build did not perform too well. WP tells us that some of the battle-damaged Dutch ships were “abandoned by their Portuguese and French allies [and] had to sail back to England to make repairs.”

Ireland joins the English/Scottish tumult; English parliament ups its challenge of King Charles

You recall how last year it was the Scottish Presbyterians whose pressure forced King Charles to make concessions to the English parliament (and to them!) This year, it was Ireland that joined the fray. This WP page on King Charles I describes the complex situation there quite well:

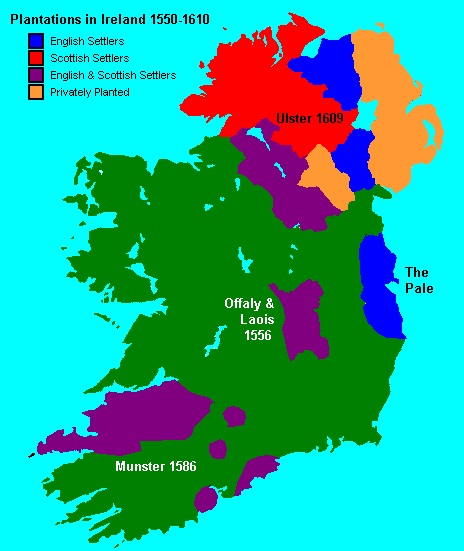

In Ireland, the population was split into three main socio-political groups: the Gaelic Irish, who were Catholic; the Old English, who were descended from medieval Normans and were also predominantly Catholic; and the New English, who were Protestant settlers from England and Scotland aligned with the English Parliament and the Covenanters. Strafford’s administration [he was the king’s buddy who was Governor of Ireland and was executed at the insistence of the English parliament in April 1641] had improved the Irish economy and boosted tax revenue, but had done so by heavy-handedly imposing order. He had trained up a large Catholic army in support of the king and had weakened the authority of the Irish Parliament, while continuing to confiscate land from Catholics for Protestant settlement at the same time as promoting a Laudian Anglicanism that was anathema to presbyterians. As a result, all three groups had become disaffected. Strafford’s impeachment provided a new departure for Irish politics whereby all sides joined together to present evidence against him. In a similar manner to the English Parliament, the Old English members of the Irish Parliament argued that while opposed to Strafford they remained loyal to Charles. They argued that the king had been led astray by malign counsellors…

Strafford’s fall from power weakened Charles’s influence in Ireland. The dissolution of the Irish army was unsuccessfully demanded three times by the English Commons during Strafford’s imprisonment, until Charles was eventually forced through lack of money to disband the army at the end of Strafford’s trial. Disputes concerning the transfer of land ownership from native Catholic to settler Protestant, particularly in relation to the plantation of Ulster, coupled with resentment at moves to ensure the Irish Parliament was subordinate to the Parliament of England, sowed the seeds of rebellion. When armed conflict arose between the Gaelic Irish and New English, in late October 1641, the Old English sided with the Gaelic Irish while simultaneously professing their loyalty to the king…

Meantime in London, veteran parliamentarian John Pym was trying to build on the victories he had won over the king earlier in the year by pulling together a document called the Grand Remonstrance, a unified list of parliament’s remaining grievances that would be presented to the king. Here’s how WP describes it:

[T]he Grand Remonstrance summarised all of Parliament’s opposition to Charles’s foreign, financial, legal and religious policies, setting forth 204 separate points of objection and calling for the expulsion of all bishops from Parliament, a purge of officials, with Parliament having a right of veto over Crown appointments, and an end to sale of land confiscated from Irish rebels. The document was careful not to make any direct accusation against the King himself, or any other named individual, instead blaming the state of affairs on a Roman Catholic conspiracy, made the easier by the King’s reconciliation with Spain and marriage to Henrietta Maria, a Roman Catholic. In tone it was strongly against the Church of Rome, taking the side of the Puritan party in the English church in opposition to William Laud, whom Charles had appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633 and who, by implication, was therefore placed at the heart of the implied plot.

On 22 November 1641, following a protracted debate, the Grand Remonstrance was passed by a relatively narrow margin: 159 votes to 148. Its passage divided Parliament and drove some prominent parliamentarians such as [Edward] Hyde and [Viscount] Falkland who had previously been critical of the King, into the Royalist camp. At the same time, it strengthened the resolve of those who opposed what they saw as a drift toward Rome and Absolutism: Cromwell commented to [a friend] that if the Grand Remonstrance had been defeated, ‘I would have sold all I had the next morning and never seen England more; and I know there are many other honest men of the same resolution’…

The Grand Remonstrance was delivered to King Charles I on 1 December 1641, but he long delayed giving any response to it. Parliament therefore proceeded to have the document published and publicly circulated, forcing the King’s hand. On 23 December 1641, he gave his reply, refusing to remove the bishops. Charles insisted that none of his ministers were guilty of any crime so as to merit their removal and deferred any decision on Irish land until the conclusion of the war there. The king stated that he could not reconcile Parliament’s view of the state of England with his own and that regarding religious affairs, in addition to affirming his opposition to Roman Catholicism, it was also necessary to protect the Church from ‘many schismatics and separatists’.

The response, drafted in consultation with Hyde, was an attempt at moderation calculated to win back the support of more moderate members of Parliament. In spite of this and concessions including the arrest of William Laud, subsequent events made reconciliation impossible.

I guess we’ll leave this account at the end of 1641. To be continued…