In 1626 we can start to see many enduring aspects of the takeover by European colonial projects of many parts of the world.

- In the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, English and French settlers joined hands to plan and commit a genocide of the indigenous Kalinago people.

- In North America, a Dutch trader paid in trade-goods worth less than $1,200 in today’s dollars to “buy” the island of Manhattan.

- Deep in the interior of South America, Jesuits corralled Indigenous people into strategic hamlets intended for physical control, mind control, and exploitation.

- Off the coast of China, Spanish conquistadors built a big fort on the northern end of Formosa– today’s Taiwan.

- (Meanwhile, on mainland China itself Ming forces fought with the Later Jin– one of many remnants of the previous Mongol Empire– in a fateful battle.)

All this, in the above order, in today’s dispatch from 1626. Read, learn, and reflect.

In St. Kitts, English and French settlers commit anti-Kalinago genocide

In 1623, as we may recall, a group of English settlers established a settlement on St. Kitts, with the aim of turning much of the island into a series of plantations, worked by enslaved laborers, to grow export crops of tobacco and sugar. Led by a guy called Thomas Warner, they built their settlement on the west coast of the island, after winning the agreement of the local Carib (Kalinago) chief, Ouboutou Tegremante. Two years later, a group of French settlers arrived, and the two European groups agreed to divide the island between them.

But guess what, they soon encountered resistance, and Tegremante himself pretty rapidly came to regret his initial welcome. This WP page on T. Warner tells us what happened next:

In 1626, after a secret meeting with Kalinago heads from neighbouring Waitikubuli (Dominica) and Oualie, the natives decided to ambush the European settlements on the night of the next full moon. The plan was revealed to the Europeans by an Igneri woman named Barbe. She had recently been brought to St. Kitts as a slave-wife after the Kalinago raided an Arawak island. According to the French historian Jean Baptiste Du Tertre, she despised the Kalinago and had fallen in love with Warner.

The English and French joined forces and attacked the Carib at night. The colonists killed between 100 and 120 Caribs in their beds that night, with only the most beautiful Carib women spared to serve as slaves. The French and English set about fortifying the island against the expected invasion of Carib from other islands.

According to Du Tertre, in the ensuing battle, three to four thousand Caribs took up arms against the Europeans. He did not estimate the number of Caribs killed, but said the fallen Amerindians on the beach were piled high into a mound. The English and French suffered at least 100 casualties. Others report that at Bloody Point, which then was the site of the island’s main Kalinago settlement, over 2,000 Kalinago men were massacred. Many had come from Waitikubuli, planning to attack the Europeans the next day. The Europeans dumped the dead into the river, at the site of the Kalinago place of worship. For weeks, blood flowed down the river, for which it was named Bloody River. The Europeans deported the remaining Kalinago to Waitikubuli.

The early accounts were by Europeans and told from their point of view. Modern scientists and historians estimate that many of their claims were fraudulent or exaggerated in order to justify the killings.

And what happened next?

After the Kalinago Genocide of 1626… Warner imported many thousands of African slaves for labour. They were forced to develop and work on large sugar and tobacco plantations to raise commodity crops for export. As the years passed, Sir Thomas Warner amassed a wealth that would amount to over £100 million in today’s terms.

Dutch trader “buys” Manhattan for a few trinkets

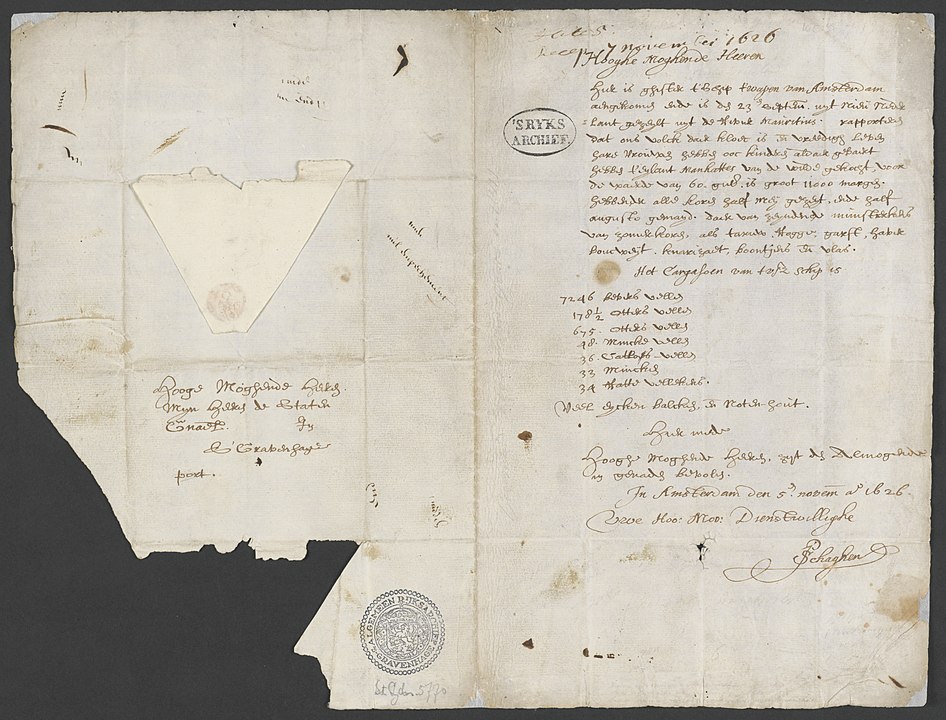

Peter Minuit was a Dutch trader who had married a rich women. He joined the Dutch West India Company (GWC) and in 1625 was sent with his family to search for tradable goods (or minerals!) other than the animal pelts that was the young colony’s main export till then. In 1626, he was named Director of the whole fairly extensive colony.

Minuit speedily thereafter “bought” the island of Manhattan from Seyseys, chief of the local Canarsee group of Lenni Lenape language speakers. The Canarsees were, this WP page says, “only too happy to accept valuable merchandise in exchange for an island that was mostly controlled by the Weckquaesgeeks.” (That is, not by the Canarsees themselves.) Minuit “paid” for the purchase with trade-goods worth 60 guilders.

The figure for the value of the trade-goods was included in a November 1626 letter that GWC board member Pieter Schagen sent to the Dutch States-General (parliament). 60 guilders translates into under $1,200 in today’s money.

The WP page on Minuit also includes this:

According to researchers at the National Library of the Netherlands, “The original inhabitants of the area were unfamiliar with the European notions and definitions of ownership rights. For the Indians, water, air and land could not be traded. Such exchanges would also be difficult in practical terms because many groups migrated between their summer and winter quarters. It can be concluded that both parties probably went home with totally different interpretations of the sales agreement.”

Fwiw, in 1631, the GWC suspended Minuit from his position, for unclear reasons.

A final footnote: Minuit returned to Europe in 1631 but a few years later re-emerged as head of a new Swedish project to establish a Swedish colony in North America. Sort of a colonizer-for-hire arrangement, I guess. Minuit and his group voyaged from Sweden to N. America in 1638 and constructed a fort called Fort Christina at an area on the Delaware River that the Dutch had earlier claimed as part of New Netherland. (It is now Wilmington, DE.) The colony of “New Sweden” never amounted to much and the Dutch (re-)captured the area in 1655.

Jesuits corral Indigenous people in S. American interior into strategic hamlets

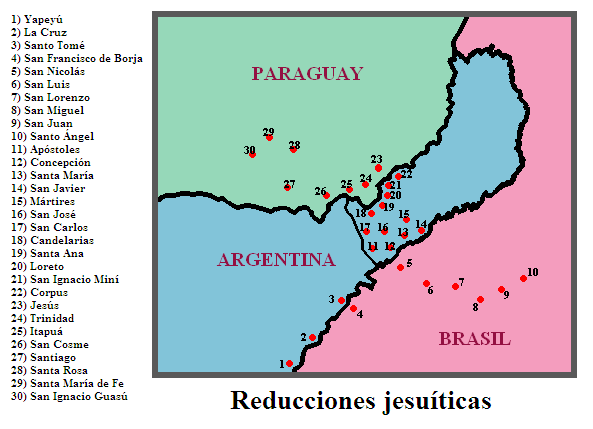

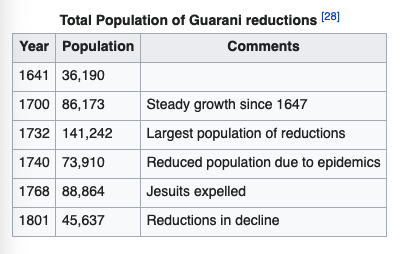

In 1626, the Jesuits who were an integral part of the Spanish conquista project in many parts of the Americas, established the Reducción de Santa María la Mayor in the deep interior of South America. It was one of 30 Jesuit “Reductions” in a Guaraní-populated area of the panhandle at the northwest of today’s Argentina that thrusts up into the space between Paraguay and Brazil.

The Reductions were a form of colonial practice, used in several other parts of South America as well, that the Jesuits pursued with particular enthusiasm. They are best understood as analogous to the strategic hamlets the United States established in South Vietnam during the war against the Vietcong guerrillas there. I’m not sure what the name was originally intended to denote– perhaps the goal of reducing the “Indian-ness” of the Indigenes? But you can think of these strategic hamlets as being intended drastically to “reduce” the access that the Indigenes captured inside them could have with their own native lands outside the Reduction, as well as the contact they could have with their family members and friends still outside them.

The Reductions were also, since they were established and tightly controlled by the Jesuits, a crucial colonial tool for mind control, aka cultural genocide. That is, they were intended to further the Spanish monarchs’ continuing campaign to convert all the peoples of South America to Catholic Christianity, by force if necessary.

This WP page on the Jesuit Reductions tells us this:

In their newly acquired South American dominions the Spanish and Portuguese Empires had adopted a strategy of gathering native populations into communities called “Indian reductions” (Spanish: reducciones de indios) and Portuguese: “redução” (plural “reduções”). The objectives of the reductions were to impart Christianity and European culture. Secular as well as religious authorities created “reductions”.

The page also tells us– somewhat bizarrely, in my view– that, “The Jesuit reductions have been lavishly praised as a ‘socialist utopia’ and a ‘Christian communistic republic’.” (The footnote there goes to a 1993 book published by the leftwing UK publisher Verso.) But I guess there was also a long period in which the “kibbutz” settlements that the Zionists established in Palestine were also described as “socialist utopias.” Sigh.

(The banner image at the top is a recent photo of the ruins of the Santa Maria Reduction.)

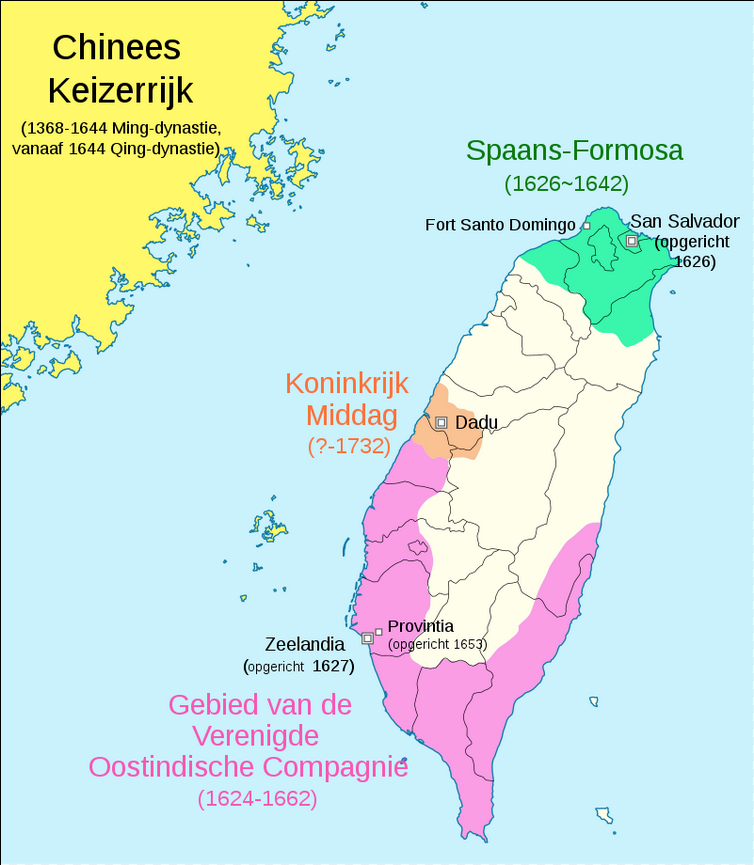

Spanish build a big fort on Formosa (Taiwan)

No, in 1626, the Spanish empire was by no means dead!

You may recall that two years ago, the Ming navy had expelled the Dutch VOC adventurers out of the Pescadores Islands and onto the southwestern end of Formosa, today’s Taiwan, where they set about building a large fort. Well, the Chinese were not the only power in the region that was concerned about the intrusion of the Dutch. So were the naval authorities in the Spanish-controlled Philippines (which bizarrely were still administered from the distant Viceroyalty of New Spain, that is, today’s Mexico.)

In 1626, the Governor-General of the Philippines sent an expeditionary force to Formosa to establish a Spanish position there. English-WP tells us this about their activities:

Landing at Cape Santiago in the north-east of Formosa but finding it unsuitable for defensive purposes, the Spanish continued westwards along the coast until they arrived at Keelung. A deep and well-protected harbour plus a small island in the mouth of the harbour made it the ideal spot to build the first settlement, which they named Santissima Trinidad. Forts were built, both on the island and in the harbour itself.

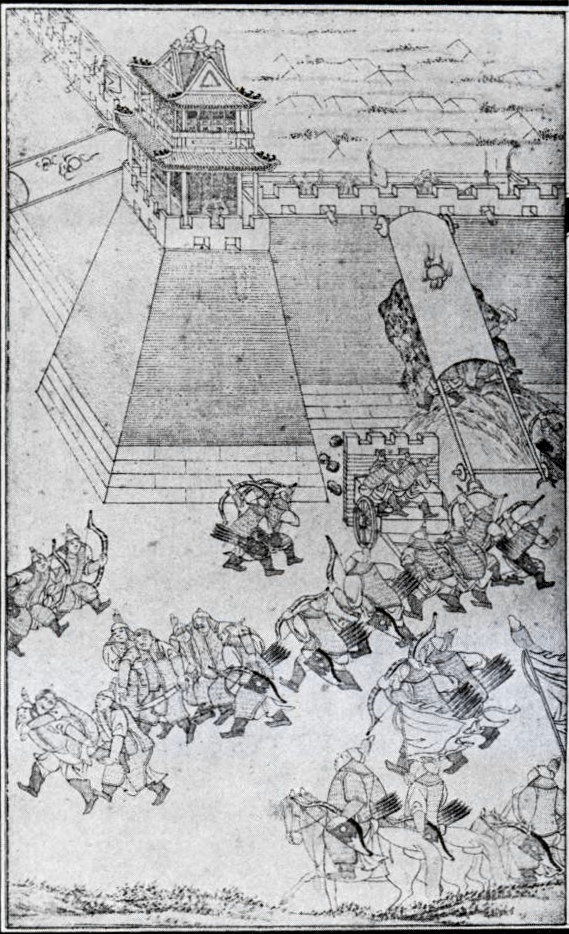

In China, Ming forces engage the Later Jin in a fateful battle

MIng-dynasty China had been battling the northern grouping known as the Later Jin for many decades. We’d met the Later Jin and their leader Nurhaci back in 1610, when he broke the Later Jin’s previous ties with the Ming, and they’d been fighting off and on ever since.

In late 1625, the Ming commander Yuan Chonghuan decided to take a strong stand against the Later Jin at the coastal city of Ningyuan, a little northeast of Beijing. He led a force of between 60,000 and 130,000 fighters that in February 1626 tried to take the big Chinese fort at Ningyuan. There was a large-scale battle there. Nurhaci’s forces were defeated and he himself was badly wounded, dying of his wounds eight months later.

He was succeeded by his eighth son, Hong Taiji. Remember that name.