Well, I am so glad I made a strategic decision yesterday not to pay too much attention in my work on this project to the minutiae of developments within land-based empires. Because this year, 1618 CE, an event happened in Prague that launched the extremely complex series of Central European conflicts that became known ever after as the Thirty Years War.

Of course, no-one set out one day and said, “Oh, let’s start a war that will last thirty years, devastate most of Central Europe, and end up killing 20% of the area’s entire population.” (Just as no-one in late 2001 said, “Let’s start an invasion of Afghanistan that will last twenty or more years and result in the devastation of broad areas of the already deeply impoverished country and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of its people.”)

So per my “concentrate on the maritime powers” ukaz of yesterday, today I’ll give a super-brief description of what happened in Prague and what it led to and mention a couple of other big stories of 1618 before proceeding to the main story in today’s bulletin: the intense machinations happening in Netherlands in 1618-19.

1618’s non-Dutch news in brief

** In February, as we know from yesterday, the possibly unhinged Ottoman Sultan Mustafa I was persuaded by his mom to step aside in favor of his 14-year-old nephew Osman II.

** Later in 1618, the new Sultan (or more likely, his mother?) concluded the Treaty of Serav with the Persian Safavid empire. In 1612, the two empires had concluded an earlier peace agreement, the Treaty of Nasuh Pasha; but since then it had frayed a bit. This new treaty reaffirmed the basic terms of the earlier one but halved the “tribute” that Persia should pay to the Ottomans. WP tells us that, “In the following decades there were times when the Ottomans succeeded to storm Tabriz, and there were times when the Persians successfully captured Baghdad. But these victories were all temporary and the balance of power between the two states continued up to the 20th century.”

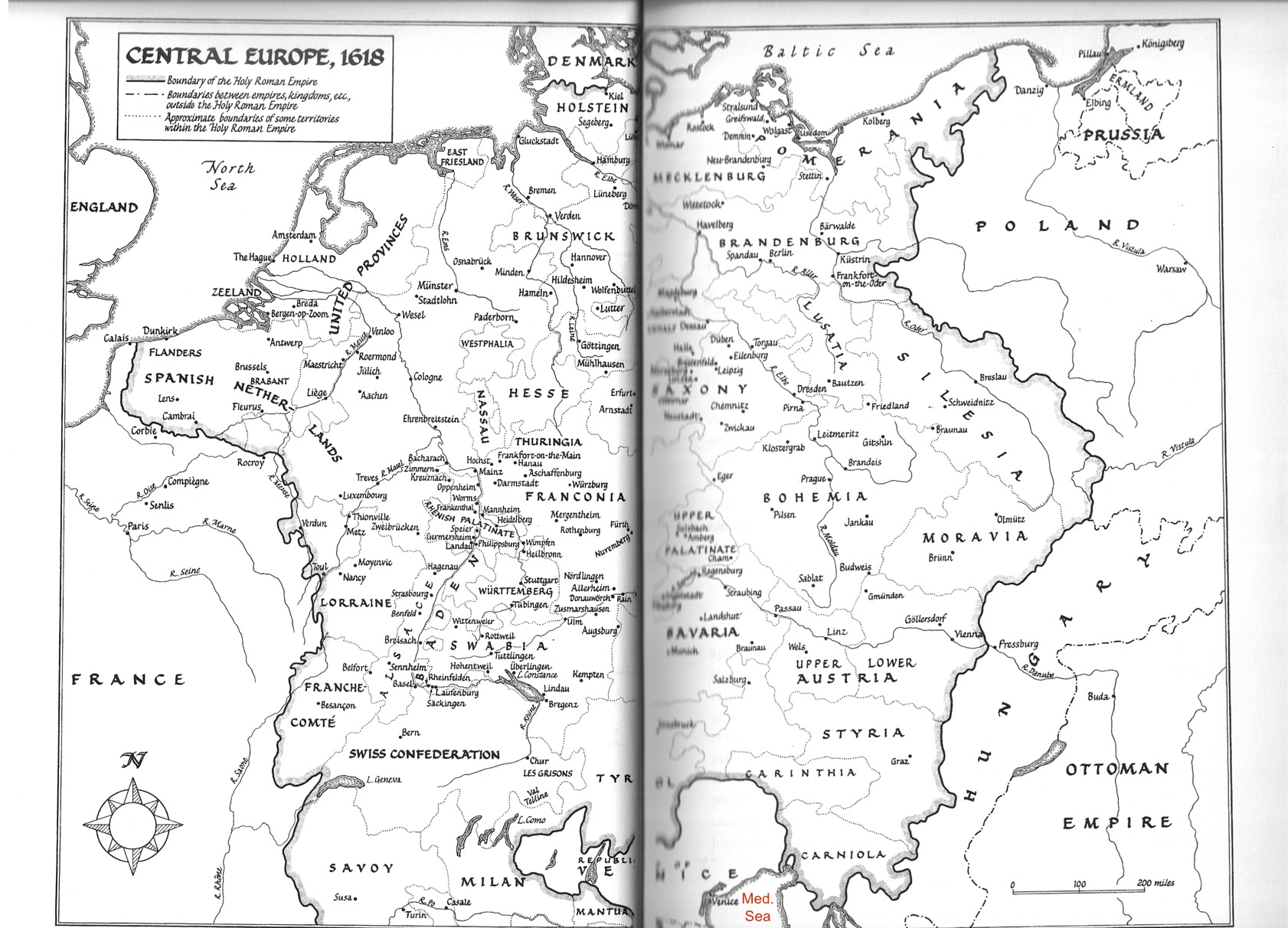

** In May, Protestant noblemen in Prague held a mock trial, and threw two direct representatives of Ferdinand II of Germany (Imperial Governors) and their scribe out of a window into a pile of manure. That escalated an existing low-key rebellion into the Bohemian Revolt of 1618–1621, which was an opening portion of the Thirty Years’ War, which would ravage Central Europe until 1648. The map here is from Peter Wilson’s 2009 book The Thirty Years War: Europe’s Tragedy, which I heartily recommend. (The banner image above is a 19th-century rendering of the defenestration.)

** Back in 1603, the English pirate-leader and adventurer Walter Raleigh had been found guilty of the “Main Plot” against James I and was imprisoned, apparently for life. In 1617, the king, short of money as so often, gave the 65-year-old Raleigh a pardon on condition that he voyage to present-day Venezuela and discover the long-sought “El Dorado”. During the voyage, someone in his expedition attacked a Spanish outpost, though King James had forbidden this since he was at peace with Spain. The Spanish demanded Raleigh be tried, which the English did; and at Spain’s insistence he was given a death sentence. Raleigh was beheaded in the Old Palace Yard at the Palace of Westminster on 29 October 1618.

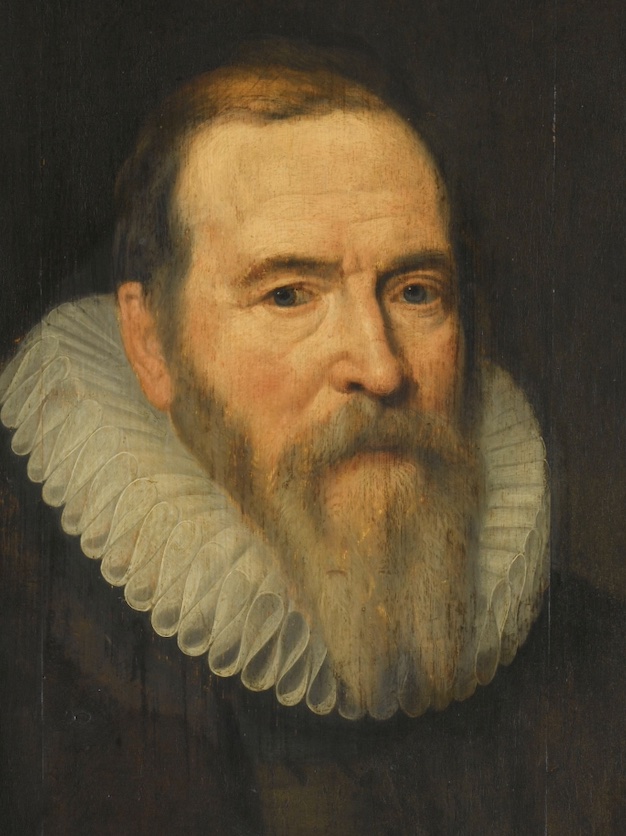

Political upheavals in Netherlands

Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt (hereafter JVO) was the grand old man of the hard-fought independence that the seven “United Provinces” of the Netherlands had wrested from the Catholic and Spanish-dominated “Holy Roman Empire” in 1579-81. Having previously studied law at at Leuven, Bourges, Heidelberg and Padua, he was one of the leading architects of the political arrangements that enabled the UP’s to work together. Since 1586 he had been the “Land’s Advocate of Holland for the States of Holland and West Friesland”.

English-WP tells us this:

This great office, given to a man of commanding ability and industry, offered unbounded influence in a multi-headed republic without any central executive authority. Though nominally the servant of the States of Holland, Van Oldenbarnevelt made himself the political personification of the province which bore more than half the entire charge of the union. As mouthpiece of the ridderschap (College of Nobles), with one vote in the States of Holland, he practically dominated that assembly. In a brief period, he became entrusted with such large and far-reaching authority in all details of administration, that he became the virtual Prime minister of the Dutch republic.

Given the precarious geopolitical positioning of the UP’s, the infant republic’s diplomacy was super-important to its survival; and in a Europe in which every late-feudal lord was expected to have loyalty to some “sovereign” monarch, after the UP’s seceded from the Holy Roman Empire JVO had strongly favored swearing loyalty to England’s Queen Elizabeth. She declined the offer, though she briefly designated her favorite, the Earl of Leicester, to be her representative to the UP’s.

Throughout that period of the late 16th century, when the Spanish land armies were continuing to beat the hell out of the UP’s, JVO was in a close alliance with the key Dutch military leader William the Silent and then William’s son Maurice of Nassau. From 1589 on, Maurice had held the office of Stadholderate of five of the seven provinces in addition to being the Captain-General and Admiral of the Union.

Oh and did I mention that JVO was also the chief architect of the very powerful Dutch East India Company, the VOC, which by 1618 had already demonstrated its massive abilities to (a) undertake hugely successful armed trading voyages to the East Indies, (b) subdue local rulers in key E. Indies locations and grab the products of their tropical islands, ( c) make mammoth profits for the Dutch investors, which formed an essential financial underpinning for the UP’s continuing war efforts at home, and (d) continue to attract investors due to its highly innovative legal-financial structure, which marked the birth of capitalism as we still know it today?

So what could possibly intervene in this relationship between JVO and Maurice of Nassau to bring an end to a partnership of such great value and impact for both of them? Yes, it was 1617-18, and the subject of their difference was theological.

Theirs was the difference between two Protestant groups known as the Arminians and the “strictly Calvinist” Gomarists. I do not pretend to understand the difference between the two groups, but it was deep enough that in 1617 or so JVO tried to lead the “States of Holland” (which was easily the dominant component within the UP’s) to secede from the Union.

The inter-religious quarrels also started to lead to unrest on the streets. JVO proposed that the States of Holland should, on their own authority, as a sovereign province, raise a local force of 4000 men (waardgelders) to keep the peace. And on 4 August 1617, he and his supporters in the States of Holland had also adopted a resolution, the Scherpe Resolutie, by which all magistrates, officials and soldiers in the pay of the province “were, on pain of dismissal, required to take an oath of obedience to the States of Holland and to be held accountable not to the ordinary tribunals but to the States of Holland.”

The States-General of the Republic (that is, of the whole UP’s) understandably saw those as secessionary moves and decided to take action. A commission was appointed, with Maurice at its head, to compel the disbanding of the waardgelders.

On 31 July 1618, Maurice, at the head of a body of troops, appeared at Utrecht, which had thrown in its lot with Holland. “At his order the local militias laid down their arms. His progress through the towns of Holland itself met with no military opposition. JVO’s ‘States party’ was crushed without any battles being fought.”

At the end of August, at the order of the States-General, JVO and his leading supporters– who included the already wildly famous international jurist Hugo Grotius– were all either arrested or removed from their government positions.

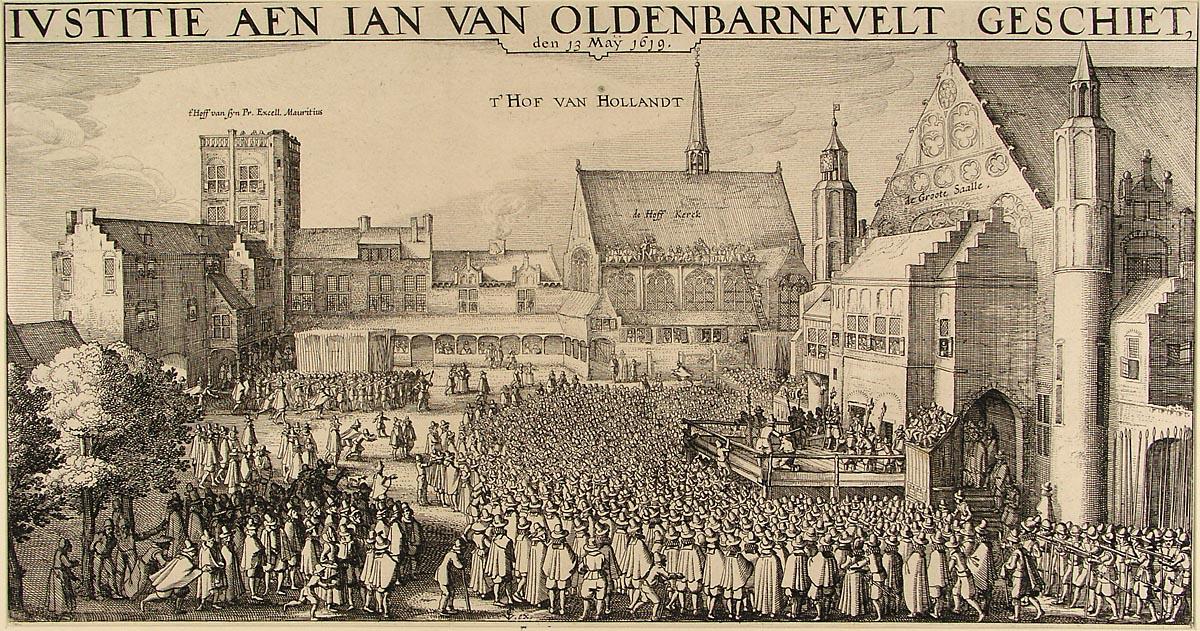

Both JVO and Grotius were among the arrested. JVO was hauled up before a specially-convened court. English-WP tells us that, “On Monday, 13 May 1619, the death sentence was read to Van Oldenbarnevelt; and, therefore, on the same morning, the old statesman, at the age of seventy-one, was beheaded in the Binnenhof, in The Hague.”

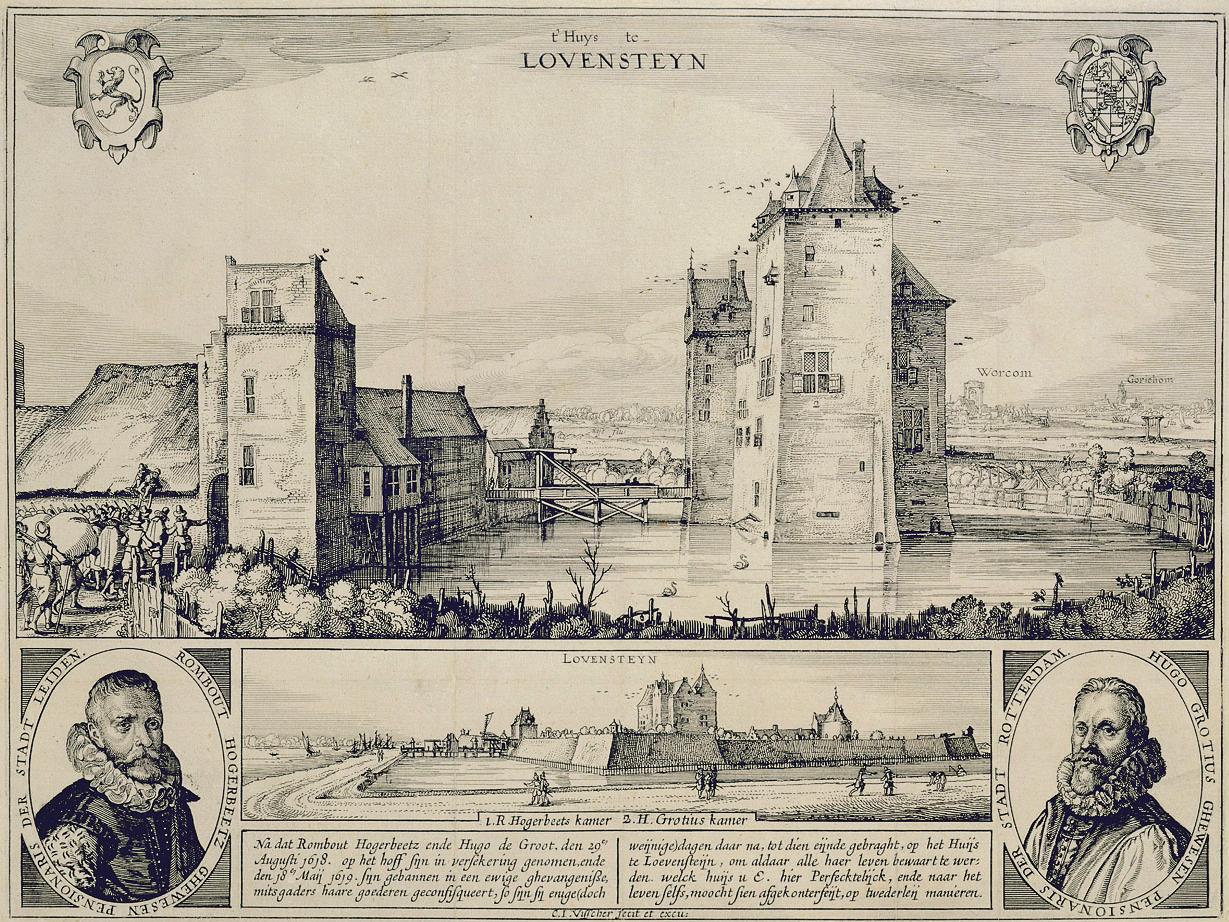

As for Grotius, he was sentenced to life imprisonment and transferred to Loevestein Castle. English-WP tells us that while there, he wrote an account of his view of church-state relations that read in part:

as to my views on the power of the Christian [civil] authorities in ecclesiastical matters… I may summarize my feelings thus: that the [civil] authorities should scrutinize God’s Word so thoroughly as to be certain to impose nothing which is against it; if they act in this way, they shall in good conscience have control of the public churches and public worship – but without persecuting those who err from the right way.

Even more famously, in 1621 Grotius was able to escape from Loevenstein Castle by being carried out in a book chest. He fled to Paris, where he continued his research and writing on philosophical and international-law topics.