1598 CE was a year of numerous developments in world affairs. Some empires saw setbacks, some saw steps forward– and two, the Spanish and the English, saw both happening in different parts of their operations.

Here were the main developments, in mainly chronological order:

Russia’s Tsar Feodor died

To no-one’s surprise he was replaced by his ambitious and wily brother-in-law Boris Godunov. His election as Tsar was proposed by none other than Patriarch Job, whose appointment as the first patriarch of an autocephalous Russian Orthodox Church he had earlier engineered. English-WP tells us of Boris: “During the first years of his reign, he was both popular and prosperous, and ruled well. He recognized the need for Russia to catch up with the intellectual progress of the West and did his best to bring about educational and social reforms.”

France’s King Henry IV does deal with Huguenots– and Spain’s Philip II acknowledges defeat in France

The Edict of Nantes that King Henry issued in April permitted nearly full rights in the country to the Protestant Calvinists known as Huguenots. The Edict “treated some Protestants for the first time as more than mere schismatics and heretics and opened a path for secularism and tolerance. In offering a general freedom of conscience to individuals, the edict offered many specific concessions to the Protestants, such as amnesty and the reinstatement of their civil rights, including the right to work in any field, even for the state, and to bring grievances directly to the king.” It marked an end to the Wars of religion that had plagued France for decades– and marked a particular setback for the local “Catholic League” and the League’s main backer, Spain’s King Philip II.

Things were not going well for the ageing Philip. He’d suffered the defeat (and massive financial setback) of the 3rd Armada against England the year before and clearly felt his long campaign to win Catholic domination of all of Europe was not now within reach. In May, he concluded the Treaty of Vervins with Henry of France, ending many decades of war (both declared and undeclared) between their two countries.

(The banner image above is a painting of the signing of the Treaty of Vervins, by Gillot Saint-Evre.)

Irish rebels inflict big defeat on English at Yellow Ford

In summer, the English “Lord Deputy of Ireland” sent an army of about 4,000 led by Henry Bagenal from the securely English-held area of “the Pale” to relieve a fort being besieged in Blackwater, to the West. As it marched from Armagh to the Blackwater, the column was routed by a Gaelic Irish army under Hugh O’Neill of Tyrone. During the fighting, Bagenal was killed by an Irish musketeer and scores of his men were killed and wounded when the English gunpowder wagon exploded. About 1,500 of the English army were killed and 300 deserted. After the battle, the Blackwater Fort surrendered to O’Neill.

Enhlish-WP concluded this: “The battle marked an escalation in the war, as the English Crown greatly bolstered its military forces in Ireland, and many Irish lords who had been neutral joined O’Neill’s alliance.”

Spain’s King Philip II dies

He was succeeded by his 20-year-old son King Philip III of Spain (Philip II of Portugal), often described as “the Pious.”

English-WP’s summary of the legacy of the departed Philip II was:

Under Philip II, Spain reached the peak of its power. However, in spite of the great and increasing quantities of gold and silver flowing into his coffers from the American mines, the riches of the Portuguese spice trade, and the enthusiastic support of the Habsburg dominions for the Counter-Reformation, he would never succeed in suppressing Protestantism or defeating the Dutch rebellion. Early in his reign, the Dutch might have laid down their weapons if he had desisted in trying to suppress Protestantism, but his devotion to Catholicism would not permit him to do so. He was a devout Catholic and exhibited the typical 16th century disdain for religious heterodoxy; he said, “Before suffering the slightest damage to religion in the service of God, I would lose all of my estates and a hundred lives, if I had them, because I do not wish nor do I desire to be the ruler of heretics.”

Dutch merchants send second expedition to Asia

The 1596 Dutch merchants’ expedition to the “Spice Islands” of South-East Asia had been judged successful enough that in 1598 the Compagnie van Verre, joining with another joint-stock company, was able to to raise nearly 800,000 guilders, “the most money that had ever been raised in the Netherlands for a private venture”, to undertake a follow-up.

This expedition consisted of eight armed merchant ships, which reach Banten (Bantam) in Java, in seven months. “The Bantamese received the Dutch eagerly, because they had recently fought with the Portuguese and destroyed three of their ships, so they hoped to gain protection from any vengeful Portuguese fleets by forging an alliance with [the Dutch commander]. Within one month he had filled all three ships full of spices.”

A subset of the fleet had, however, been blown of course in the Indian Ocean. They landed on the island the Portuguese had known as Do Cerne, which they promptly renamed “Mauritius” in honor of Dutch leader Maurice of Nassau.

Most of the ships would arrive safely back in Amsterdam in mid-1600, where they received a brass-band welcome. The expedition netted a 400% profit for its investors.

Big defeat for the Japanese in Korea

In mid-December 1598 (Gregorian), there was a large-scale sea battle in the Noryang Strait off the south coast of Korea. It pitted a Japanese force of 300-500 ships that was trying to join up with another Japanese fleet in the area )and to resupply Japanese invasion forces on Korea) against a joint Chinese-Korean (Joseon) naval force sent to intercept it. The Joseon navy, commanded by very smart admiral Yi Sun-sin, had 148 ships and their Ming Chinese allies, led by admiral Chen Lin, had 63 ships. Virtually all these ships in the allied fleet were sturdy fighting vessels, however, whereas many of the Japanese ships were light troop-transports.

The area of the Noryang Strait has numerous islands, so as with the previous year’s sea-battles between these protagonists a close knowledge of the often narrow waterways and tides was essential. The allied fleet waited for the expected Japanese fleet on the west end of Noryang Strait. The battle began around 02:00 am on 16 December. “It was, from the very beginning, a desperate affair with the Japanese determined to fight through the allied fleet and the allies equally determined to keep them from breaking through and advancing.”

Long story short, the Chinese-Korean fleet managed to win, inflicting heavy damages on the Japanese. During the battle, however, Korea’s Admiral Yi was struck in the heart by a stray bullet, which killed him. His last reported words were, “We are about to win the war – keep beating the war drums. Do not announce my death.” So his nephew climbed into his uncle’s armor and continued to beat the war drum on the flagship.

But Yi was right. They were winning– and not just that battle. The Japanese realized their invasion troops in Korea were now all extremely vulnerable and shipped them all back to Japan within days.

Mapuche inflict defeat on Spanish in Chile

The Battle of Curalaba was a meticulously planned ambush that the Mapuche of south-central Chile sprung at the very end of 1598 on Martín García Óñez de Loyola, the “Royal Governor of the Captaincy General of Chile.” Óñez was determined to quell the ever-rebellious Mapuche of the region and had traveled there at the head of a force of some 50 men to do so…

English-WP takes up the story: “The Mapuche people, aware of their presence, with their cavalry led by Pelantaru and his lieutenants, Anganamón and Guaiquimilla, with three hundred men, shadowed his movements and made a surprise night raid. Completely surprised, the governor and almost all of his soldiers and companions were killed.”

(Several years later, the Mapuche returned Óñez’s head to the next Governor of the “Captaincy”.)

Not surprisingly, the Spanish called the event the “Disaster of Curalaba.” But worse was to come for the invaders. The Battle of Curalaba energized many Mapuches throughout the region and over the following six years they destroyed seven other Spanish settlements in the region.

This page on English-WP offers these intriguing further details about the “Destruction of the Seven Cities”:

Contemporary chronicler Alonso González de Nájera writes that Mapuches killed more than 3,000 Spanish and took over 500 women as captives. Many children and Spanish clergy were also captured. Skilled artisans, renegade Spanish, and women were generally spared by the Mapuches. In the case of the women it was, in the words of González de Nájera, “to abuse them” (Spanish: aprovecharse de ellas).

While some Spanish women were recovered in Spanish raids, other were set free only in agreements following the Parliament of Quillín in 1641. Some Spanish women became accustomed to Mapuche life and stayed voluntarily among the Mapuche. The Spanish understood this phenomenon as a result either of women’s weak character or their genuine shame over having been abused. Women in captivity gave birth to a large number of mestizos, who were rejected by the Spanish but accepted among the Mapuches. These women’s children may have had a significant demographic impact in the Mapuche society, which was long ravaged by war and epidemics.

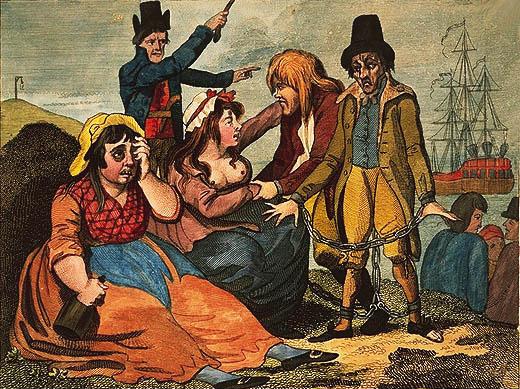

English Parliament adopts the “Vagabonds Act”

The people of England (as opposed to the swaggering lords, investors, and royalty who had made so much money from their piracy on the high seas) were having a hard time of it economically in the late 1590s. There had been a recurrence of plague and a few years of poor harvests. “In London alone there were an estimated 10,000 vagabonds; and 2,000 in Norwich.”

There was a lot of talk in parliament about the twin issues of how to deal with these (actually very needy) vagrants, and reform of the penal system more broadly. Earlier in the century, during the 38-year reign of Henry VIII, it was estimated that some 72,000 people in England had been executed…

Parliament’s solution was legislation that would offer to those given a death sentence the alternative that they might be transported overseas instead. This would become a key part of British settler colonialism over the centuries that followed.

Spanish in North America establish “New Mexico”

In 15987, the Spanish province province of “New Spain” (later, Mexico) established a sub-province called “Nuevo México”, further to the north. The first Spanish governor of this first “New Mexico” was the now-infamous conquistador Juan de Oñate, best known for the brutality he showed against the Indigenes during the 1599 Acoma Massacre.

Pre-Spanish peoples of the southwest-US area

Area of “Neuvo Mexico”