I think the “big” story this year, 3 years after the defeat of the Spanish Armada and generally undaunted by the 1589 defeat of the English Counter-Armada, is to see how many different naval expeditions the various investors’ groups of London were launching, to numerous different parts of the Spanish-dominated world…

But before we look at the details of those, some quick historical “bullet-points” for 1591 CE (all details from English-WP):

- Throughout the Netherlands, the Protestant forces (often with direct backing from London) registered several significant victories. The Dutch Protestants captured Zutphen in May, Deventer in June, Knodsenburg in July, Hulst in September, and Nijmegen in October. In France, Henry IV tried with British help to capture Rouen from the Catholic League but was unable to.

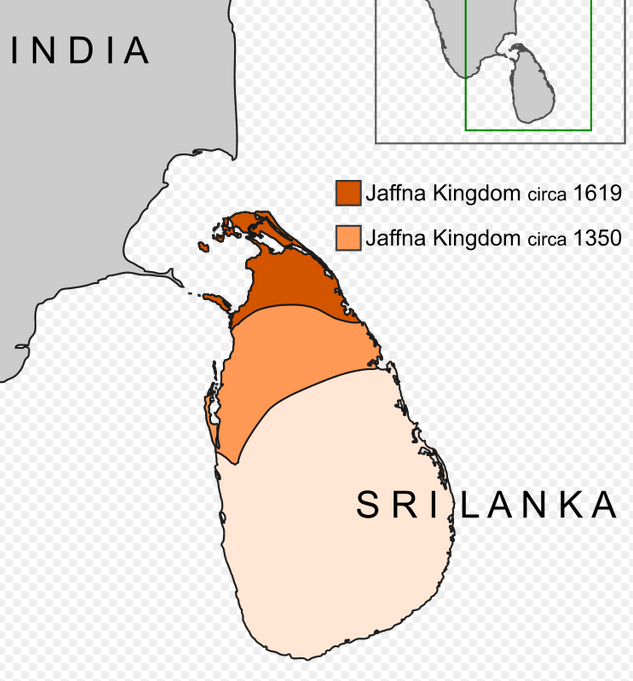

- In today’s Sri Lanka, October 1591 saw a Portuguese invasion of the Jaffna Kingdom in the north of the island. The invasion force, led by André Furtado, consisted of 1,400 Portuguese soldiers and 3,000 Lascarins (conscripted indigenes), who sailed from further south in Sri Lanka in 43 ships and more than 200 small vessels. The Portuguese captured King Puvirasa Pandaram. Furtado ordered him beheaded: “His head was then placed on a pike and kept on display for several days. The palace was sacked and the king’s entire family was taken captive.” More than 800 members of Puvirasa’s defense force were also beheaded. All the vessels in the port were burnt except two vessels for the use of the new, Portuguese-installed king.

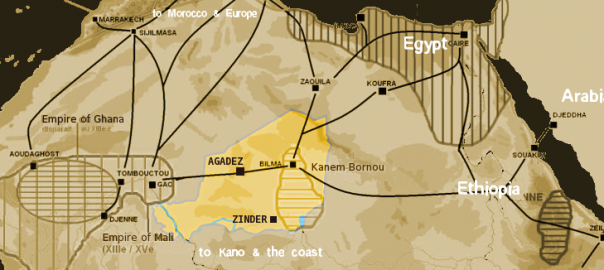

- In north-west Africa, in March, the Saadi ruler of Morocco sent a force under Judar Pasha to fight the Songhai Empire in Tondibi, in today’s Mali. Judar Pasha won that battle, sending the Songhai Empire into disarray. Judar then pushed on to the relatively very wealthy city of Timbuktu, which his fighters conquered in late May. Much of the wealth of Timbuktu– and some of its leading scholars such as Ahmad Baba– were hauled back to Marrakesh. (More info at this page on WP.) But the cross-Sahara trade routes were anyway starting to lose out to the naval trade routes being strengthened around West Africa by the Portuguese and other European “big ship” nations. (The banner image above shows the trans-Sahara trade routes as of around 1400 CE.)

- In Russia, Tsarevich Dimitri, at eight years old the very much younger brother of Tsar Feodor, was found dead in mysterious circumstances, at the palace in Uglich. The official explanation was that he had cut his own throat during an epileptic seizure, but many believed he was put out of the line of succession by Feodor’s powerful brother-in-law, Boris Godunov.

And now, the main action…

English adventurers spread their sails

I put the following together from lots of bits and pieces around English-WP; but together I think they add up to something noteworthy:

- In April, James Lancaster set out from Torbay, Devon with a fleet of three ships on a voyage around the Cape of Good Hope heading for the East Indies. They reached Penang on the Malay Peninsula in June 1592. “Lancaster remained on the island until September of the same year and pillaged every vessel he encountered.” However, the return voyage was disastrous: only 25 officers and men survived to rewach England in May 1954. (In 1594, he also led a successful privateering expedition against Portuguese ships and warehouses in Brazil.) In 1600, when a group of London merchants formed the East India Company, Lancaster was given command of its first fleet.

- Also in April 1591, a fleet of three smaller and one larger armed English merchant vessels was attacked by a Spanish squadron in the Mediterranean, near the Straits of Gibraltar. The English ships were returning from a trading voyage made on behalf of the “Levant Company.” Five Spanish galleys approached them. The larger English ship, the Centurion, held its ground while the smaller ones retreated. The Spanish ships, each holding about 200 soldiers, all attempted to board the Centurion, attaching themselves with grappling irons, two to a side with a fifth galley on the stern. “On both sides of the ship the Spanish were repelled; the ropes and grapples were cut successively and fire was maintained to cripple the Spanish ships. In the end, the Spaniards were constrained to unfasten their grapplings and shear off as they had suffered heavy casualties and many of their ships were severely damaged.” They did manage to sink one of the smaller English ships. But the rest made it through the Straits and returned to England.

- The Blockade of Western Cuba, also known as the Watts’ West Indies Expedition of 1591, was an English privateering naval operation that took place off the Spanish colonial island of Cuba in the Caribbean. The expedition along with the blockade took place between May and July 1591 led by Ralph Lane and Michael Geare with a large financial investment from John Watts and Sir Walter Raleigh. They intercepted and took a number of Spanish ships, some of which belonged to a Spanish treasure convoy led Admiral Antonio Navarro, and protected by the Spanish navy. The English took or burnt a total of ten Spanish ships including two galleons, one of which was a valuable prize. With this success and the loss of only one ship the blockade and expedition was terminated for the return to England. The English fleet arrived at Plymouth a few months later with the eight captured ships amid much rejoicing. It had been a huge success – eight prize ships were taken in all worth a total of £40,000 which produced a return on investment of at least 200 per cent regardless of the embezzlement that crew members had committed. “Half of the profits went to Queen Elizabeth and the Lord Admiral (the Earl of Nottingham), with the rest shared between Watts and Raleigh.”

- Another English privateering expedition around that time was not so successful. This was one to Cape St. Vincent, at the extreme south-western end of the Iberian peninsula, and was led by an experienced naval adventurer called the Earl of Cumberland. He took one royal ship and four of his own. As they sailed down the coast of Spain/Portugal, they captured a total of five Spanish and Portuguese merchant ships, with their cargoes. But the Spanish viceroy in Portugal got wind of their actions and sent a squadron of five Spanish galleons to pursue them in mid-July, as the English ships headed for the Berlengas Islands. Taking advantage of the calm, the Spanish galleys rowed up, engaged and took some of the English ships “after a bloody fight.” One of the English captains and 100 other English captives ended up spending some months as a galley slave in a Spanish galley.

- And yet another English naval expedition, one to attack the Spanish Treasure Fleet in the Azores, also met a bad end in 1591. This one was a very serious, large-scale expedition mounted by John Hawkins (whom we’d met earlier as a pioneer of the dreadful “Triangle Trade”, back in 1562 or so.) But now Hawkins was Treasurer of the English Royal Navy– he’d been responsible for the naval build-up that allowed the English to hold off the Spanish Armada. His concept now was to attack the Spanish Treasure Fleet in the Azores in order to bankrupt the Spanish war effort. In this expedition, a fleet of 22 English ships set off for the Azores. But once arrived there, in late August they were surprised and overpowered by a larger Spanish fighting fleet that was had gone to meet the Treasure Fleet. There was a fierce battle but at the end of it the combined Spanish fleet sailed home having suffered only minor casualties. This battle, English-WP says, “marked the resurgence of Spanish naval power.”