It’s 1586 CE. The Ottomans and Safavids are still fighting (deep inside terrain previously held by the Safavids.) Russia’s new-ish tsar, Feodor I, founds three new cities, pushing the area of Russian control further to the south and east. But the main action of the year is clearly the Battle Royal between the English and the Spanish, as pursued in both those two countries, in Netherlands, France, and stretching far across the Atlantic Ocean, where in 1586 Francis Drake plunders and burns the Spanish settlements in both Santo Domingo (today’s DR) and St. Augustine, Florida.

But ground zero of the Anglo-Spanish contest is in England, where Elizabeth’s wily spymaster Francis Walsingham executes a patient plot to set up Mary, Queen of Scots, and then… Let the story begin.

Walsingham’s fiendish sting against pro-Spanish plotters

English-WP tells us that Francis Walsingham, born 1532, “rose from relative obscurity to become one of the small coterie who directed the Elizabethan state, overseeing foreign, domestic and religious policy.” He had served as English ambassador to France in the early 1570s and witnessed the anti-Huguenot massacre launched there in 1572 by the Catholic authorities. In December 1573 he was appointed to the Privy Council and made “principal secretary” to Elizabeth. In that role, he “supported exploration, colonization, the use of England’s maritime strength and the plantation of Ireland… Overall, his foreign policy demonstrated a new understanding of the role of England as a maritime Protestant power with intercontinental trading ties.”

He also had a lively understanding of the threats that, in a time of war with Spain, could arise to the Elizabethan state from pro-Spanish sympathizers in England’s remaining Catholic community. One intense focus of these fears was Mary, (former) Queen of Scots, the very Catholic second cousin of Elizabeth’s who had been deposed from her Scottish throne in 1567 and had been living under Elizabeth’s close surveillance in England since around that same time.

In 1571, Walsingham and his ally William Cecil had already uncovered one plot by a Florentine banker called Roberto Ridolfi to enlist Mary in a pro-Catholic coup against Elizabeth. Mary had been implicated in another anti-Elizabeth plot in 1854. Now, in 1586, Walsingham set about entrapping Mary so this could never happen again.

(The banner image above is a detail from a 17th century engraving of Elizabeth flanked by William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, and Francis Walsingham.)

Of course there were plenty of people, Catholics English and non-English, who were eager to get Mary to be their figurehead in a Catholic restoration in England. In 1586, two who made a move in this direction were John Ballard, a Jesuit priest, and his young protegee, Anthony Babington, a member of the English Catholic gentry.

During 1585, Ballard traveled to England (from, presumably, France) a number of times to secure promises of aid from the northern Catholic gentry on behalf of Mary. Then in March 1586, he met with four key conspirators, one of whom, Gilbert Gifford, had already agreed to be a double agent for Walsingham. At some point, Gifford reported to the Spanish Ambassador (maybe in Paris? maybe in London?), Don Bernardino de Mendoza, that English Catholics were prepared to mount an insurrection against Elizabeth, “provided that they would be assured of foreign support.”

Back in England, Ballard persuaded Anthony Babington to lead and organize the English Catholics to rise up against Elizabeth, telling him about the plans that had been so far proposed. Babington was reported as initially hesitant, as he thought that no foreign invasion would succeed for as long as Elizabeth remained, to which Ballard answered,essentially, that he had plans to take care of that. “After a lengthy discussion with friends and soon-to-be fellow conspirators, Babington consented to join and to lead the conspiracy.”

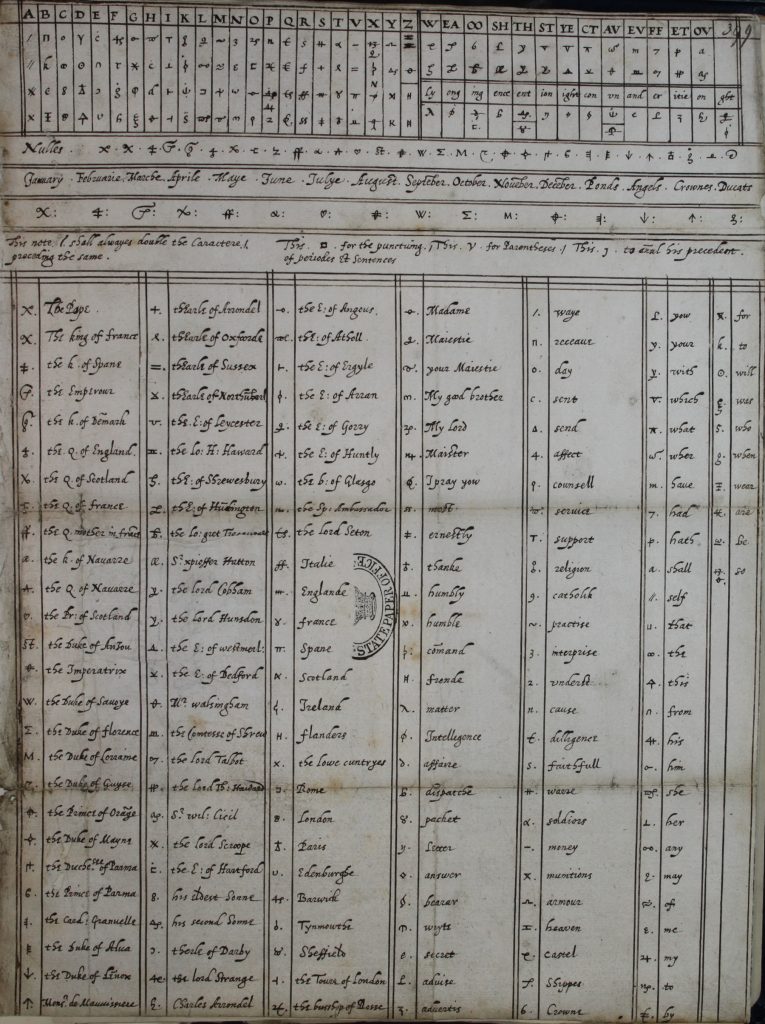

Meantime, Walsingham had made a smart plan to infiltrate Mary’s own communications. Mary was held in Chartley Hall, a country house under the close care of a trusted Elizabeth loyalist; and after the 1584 plot had been discovered, Walsingham had shut down her communications with outsiders, completely. Now, under his close care, one means of sending and receiving heavily encrypted communications was presented to her. It involved one or more sheets of paper being wadded inside the large cork bung of a beer barrel, with the help of the local brewer. Walsingham even managed to have installed in Chartley an expert cryptographer who could do all the encryption and decryption Mary needed for her own “secure” communications with the outside. The codes this guy used looked pretty sophisticated! The main person on the outside via whom she was communicating with Babington was… Gilbert Gifford.

On July 14, 1586, Mary got an encrypted message from Gifford telling her:

Myself with ten gentlemen and a hundred of our followers will undertake the delivery of your royal person from the hands of your enemies. For the dispatch of the usurper, from the obedience of whom we are by the excommunication of her made free, there be six noble gentlemen, all my private friends, who for the zeal they bear to the Catholic cause and your Majesty’s service will undertake that tragical execution.Mary was clear in her support for the murder of Elizabeth if that would have led to her liberty and Catholic domination of England. In addition, Queen Mary supported in that letter, and in another one to Ambassador Mendoza, a Spanish invasion of England.

Three days later, Mary responded, with a letter in which

Then for mine own part, I pray you to assure our principal friends that, albeit I had not in this cause any particular interest in this case… I shall be always ready and most willing to employ therein my life and all that I have, or may ever look for, in this world.

English-WP tells us that Mary was clear in her support for the murder of Elizabeth if that lead to her liberty and Catholic domination of England. In addition, she supported in that letter, and in another one to Ambassador Mendoza, a Spanish invasion of England.

Walsingham had what he needed. But he wanted more: he wanted the names of the conspirators. So he had the cryptographer make a copy of Mary’s letter to Gifford in which she allegedly “asked” for their names and for any other details about the anti-Elizabeth plot. But before Walsingham and the cryptographer got any response to this letter Mary used the beer-barrel channel to send Gifford a short letter saying simply: “Let the great plot commence. Signed Mary.”

John Ballard was arrested on August 14 and Babington shortly after. Within days, dozens of conspirators from outside Chartley Hall and Mary’s two secretaries from inside the Hall were all arrested. The seven principal conspirators– including both Ballard and Babington– were convicted of treason and conspiracy against the crown and were sentenced to death by hanging, drawing, and quartering. This was a barbaric means of execution which involved not just hanging (which can be done in a speedy manner in which the neck is broken during the fall) but also, prior to hanging having one’s entrails drawn out, and after hanging having the body be decapitated and cut into quarters.

In the case of the participants in what was called the Babington Plot, the outcry at what was done to first seven conspirators led to Elizabeth deciding that for the next seven, also convicted of treason, they should be allowed to hang until “quite dead” before disemboweling and quartering.

As for Mary, she was tried in October 1586 by a court consisting of 46 English lords, bishops, and earls, and convicted of treason and in February 1587 was executed by beheading. Her 20-year-old son remained as King James VI of Scotland and remained in alliance with Elizabeth.