Lots of not-huge things happening in 1582 CE, but together they give a good glimpse into the world of that era:

- Ming dynasty’s Zhang Juzheng dies

- Matteo Ricci enters China

- Ivan sends Cossacks under Yermak to conquer Siberia

- Pope Gregory introduces new calendar

- Conquistadoring continues

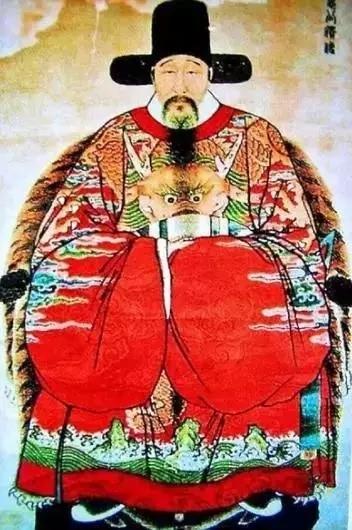

Ming dynasty’s Zhang Juzheng dies

Zhang Juzheng, born in 1525 CE, had been since 1572 the 46th Senior Grand Secretary of the Ming Dynasty, thus playing a sort of “prime ministerial” role with respect to the Wani Emperor that was analogous to the role Sokollu Mehmed Pasha had played in the Ottoman Empire– though Sokollu Mehmed’s time as Grand Vizier was considerably longer and allowed him to orchestrate two Sultanic successions in Istanbul.

There are certainly some indications that Zhang helped orchestrate the succession in Peking in 1572 of the Wanli Emperor, who succeeded his father the Longqing Emperor when he was only eight years old. (The Wanli was not the oldest son, and this WP page on the imperial succession states, “Before the Longqing Emperor died, he had instructed minister Zhang Juzheng to oversee affairs of state and become the dedicated advisor to the Wanli Emperor who was only 10.”) Eight or ten, who knows? Anyway, a pliable youngster.

Zhang was born in Hubei Province and “renowned for his intelligence at an early age.” He passed the highest imperial exams in 1547 and entered the bureaucracy– but at a time when it was riven with factionalism.

English-WP here:

He was one of few officials who had cordial relations with both Yan Song and Xu Jie, the leaders of the respective factions, but eventually assisted Xu in overthrowing Yan Song. Subsequently, under Xu’s patronage, Zhang became a Privy Secretary in 1567, outlasting Xu himself and sharing power with his political rival Gao Gong. In 1572, shortly after the accession of the Wanli Emperor, Gao was ejected from office by Zhang and his ally, the eunuch Feng Bao, on charges that he had questioned the ability of the child emperor to rule. This left Zhang as the sole Grand Secretary, in effect controlling the entire Ming bureaucracy during the first ten years of the Wanli era.

And then, the WP page on the Wanli Emperor’s period as ruler says this:

As Zhang Juzheng was appointed Minister of Ming dynasty in 1572, he launched a reform by the name of “abiding by ancestors’ rules”. He started from rectifying administration with a series of measures such as reducing redundant personnel and enhancing assessment of officials’ performance. This improved officials’ quality and efficiency of administration, and based on such facts he launched relevant reforms in the fields of land, finance, and military affairs. In essence, Zhang Juzheng’s reform was a rectification of social maladies without offending the established political and fiscal system of the Ming Dynasty. Although it did not eradicate political corruption and land annexation, it positively relieved social contradictions. More over, Zhang efficiently protected the dynasty from Japan, Jurchens and Mongols so he could save national defense expenditure. By the 1580s, Zhang stored an astronomical amount of silver, worth second only to 10 years of Ming’s total tax revenue. The first ten years of Wanli’s regime led to a renaissance, economically, culturally and militarily, an era known in China as Wanli’s renaissance (萬曆中興)). During the first ten years of the Wanli era, the Ming dynasty’s economy and military power prospered in a way not seen since the Yongle Emperor and the Rule of Ren and Xuan from 1402 to 1435.

But by the time the Wanli Emperor was 18 (or 20), he apparently felt he had chafed under Zhang’s rules for long enough. Zhang died (cause not given.) So then, this:

After Zhang’s death, the Wanli Emperor felt free to act independently, and reversed many of Zhang’s administrative improvements. In 1584, the Wanli Emperor issued an edict confiscating all of Zhang’s personal wealth and purging his family members. Especially after 1586 when he had conflicts with vassals about his heir, Wanli decided to not hold the council for 20 years. The Ming dynasty’s decline began in the interim.

As was very common (or the norm?) for high officials in Ming China, Zhang was also an intellectual. In 1573 he, “presented the Wanli Emperor with a commentary on the Four Books of the Confucian canon, entitled ‘Colloquial Commentary on the Four Books’ (四书直解, Sì Shū Zhíjie). It was published some time between 1573 and 1584. The book was not destroyed during the posthumous disgrace of Zhang, and even enjoyed a measure of renown among the Chinese literati almost a century later, during the early decades of the Qing dynasty, when several editions of it appeared between 1651 and 1683.”

Matteo Ricci enters China

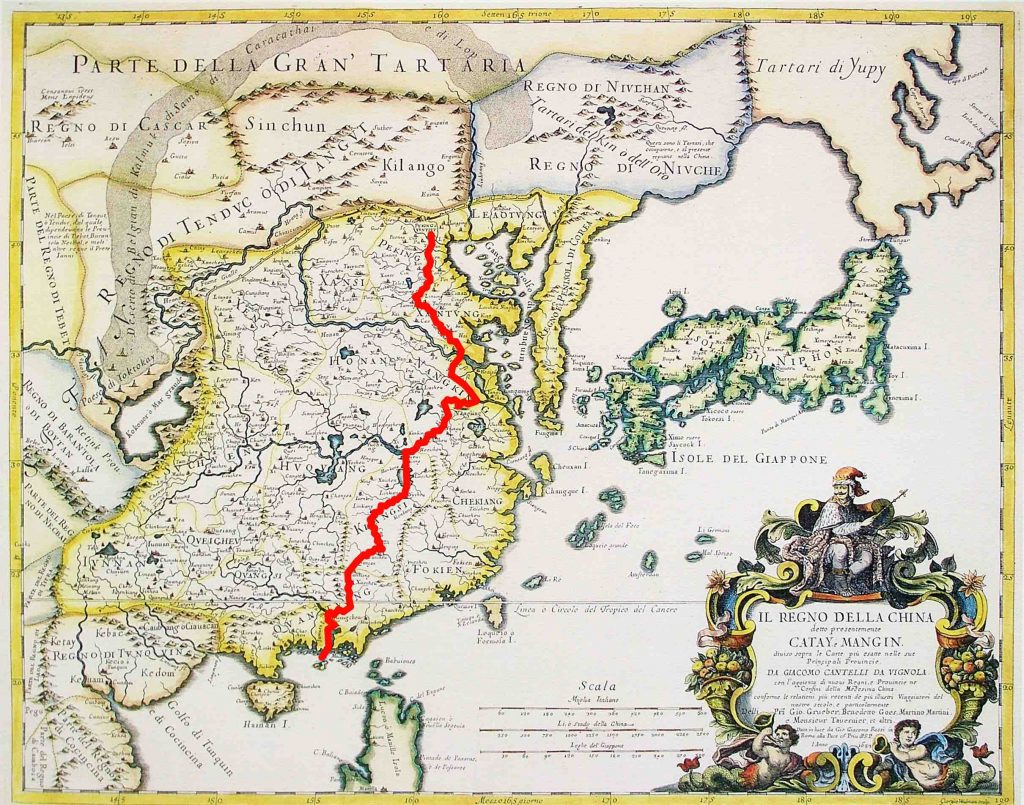

Matteo Ricci had been born in 1552 in today’s Italy and became a Jesuit in 1571. He applied to join a Jesuit missionary expedition to the Far East, and in 1578 he sailed from Lisbon to Goa in this role. In 1582 he was summoned to the Portuguese foothold in Macau in order to prepare to enter (the rest of) China. Once in Macau, he studied Chinese language and customs, along with Michele Ruggieri, a Jesuit who had started this project in 1579. Then,

With Ruggieri, he traveled to Guangdong’s major cities, Canton and Zhaoqing (then the residence of the Viceroy of Guangdong and Guangxi), seeking to establish a permanent Jesuit mission outside Macau.

In 1583, Ricci and Ruggieri settled in Zhaoqing, at the invitation of the governor of Zhaoqing, Wang Pan, who had heard of Ricci’s skill as a mathematician and cartographer. Ricci stayed in Zhaoqing from 1583 to 1589, when he was expelled by a new viceroy. It was in Zhaoqing, in 1584, that Ricci composed the first European-style world map in Chinese, called “Da Ying Quan Tu” (Chinese: 大瀛全圖; lit. ‘Complete Map of the Great World’). No prints of the 1584 map are known to exist, but, of the much improved and expanded Kunyu Wanguo Quantu of 1602, six recopied, rice-paper versions survive.

Matteo Ricci’s adventures and projects in China would, of course continue…

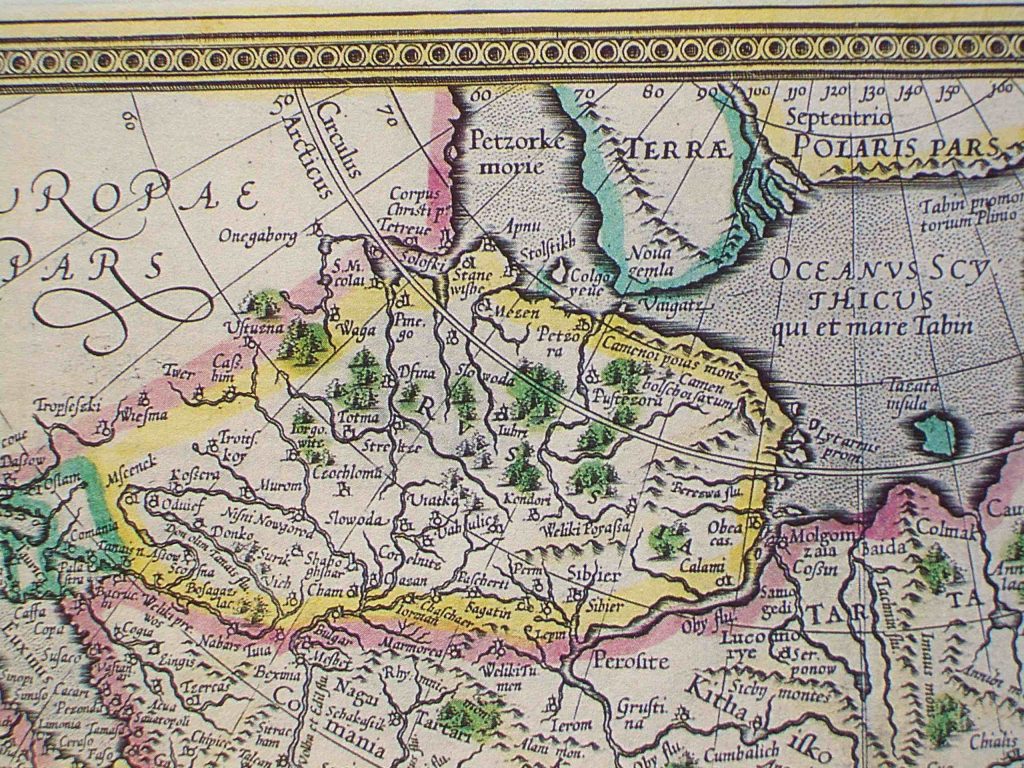

Ivan sends Cossacks under Yermak to conquer Siberia

Whoa! The English-WP page on this guy Yermak Timofeyevich is extremely lengthy. It has multiple, apparently well-sourced footnotes but also a lengthy preamble saying, essentially: “We don’t actually know much about this guy. The two main sources people use are highly contradictory and both were compiled many years after his death.”

Many parts of the page make a pretty gripping read. My main takeaways from it are as follows:

- In 1581 or so, a decision had been made– unclear if by Tsar Ivan or by members of the wealthy family the Stroganovs who had a growing merchant/colonial empire deep in the east of today’s Russia– to send this guy Yermak and his band of Cossacks on an expedition to conquer the Khanate of Sibir (Siberia), using the previously conquered Khanate of Khazan as a jumping-off point. Khazan had already become the Russian province of Perm.

- Sibir and its main town Qashliq were controlled by a Mongol-remnant (and also Tartar) khan called Kuchum.

- Yermak’s background had been as a river pirate and general reprobate.

- In the campaign against Sibir, he had an army of 840 men– about 540 of them his own followers and 300 supplied by the Stroganovs. “Nikita and Maksim Stroganov spent twenty thousand rubles of their riches to outfit the army with the best weapons available. This was especially to the advantage of the Russian detachment because their Tatar opponents did not have industrial weapons.

- “After two months, Yermak’s army had finally crossed the Urals. They followed the river Tura and found themselves at the outskirts of Kuchum Khan’s empire. Soon they reached the kingdom’s capital city of Qashliq. On October 23, 1582, Yermak’s army fought the Battle of Chuvash Cape, which initiated three days of fighting against Kuchum’s nephew, Mehmet-kul, and the Tatar army. Yermak’s infantry blocked the Tatar charge with mass musket fire, which wounded Mahmet-kul and prevented the Tatars from scoring a single Russian casualty. Yermak succeeded in capturing Qashliq and the battle came to mark the ‘conquest of Siberia’.”

- Yermak was a long way from Perm and Moscow and frequently sent back mendacious reports, leading to several fallings-out with his sponsors. He also led his men on several (presumably pretty brutal) raiding parties around the region.

- By late 1584, his band of Cossacks was in dire straits: “while Yermak had succeeded in regaining the loyalty of the [local] tribes, his men were now almost completely out of gunpowder. To make matters worse, while his reinforcements arrived, they did so utterly exhausted and depleted by scurvy… Thus, in addition to facing the problem of escalating hostilities, their food shortage was magnified by the arrival of more men. Eventually, it is reported the situation grew dire enough that Yermak’s men turned to cannibalism, eating the bodies of the deceased.”

- At some point around then, Yermak was apparently duped by Kuchum into entering a trap and was killed.

This WP page has a good list of the “legacies” of the expedition that Yermak started in 1582. First, this: “Yermak had set a precedent of Cossack involvement in Siberian expansion, and the exploration and conquests of these men were responsible for many of the additions to the Russian empire in the east.”

And also this:

The actions of Yermak also redefined the meaning of the word Cossack. While it is uncertain whether Yermak’s group was related in any way to the Yaik or Ural Cossacks, it is known that their company was previously outlawed by the Russian government. However, in sending his letter and his trusted lieutenant Ivan Kolzo to Ivan the Terrible, Yermak transformed the image of the Cossack overnight from a bandit to a soldier recognized by the Tsar of Moscow. Now, Yermak’s Cossacks had effectively been incorporated into the military system and were able to receive support from the tsar. This new arrangement also acted as a sort of pressure-relief valve for the Cossacks, who had a history of being troublesome on the Russian frontier. In sending as many of them as possible further east into unconquered lands, the burgeoning and extremely profitable lands on the borders of Russian territory were given respite. Yermak’s call for aid thus spawned a new type of Cossack which, by virtue of its link to the government, would enjoy significant favor from future Russian rulers.

Lots of parallels there to the way that in Western-European countries, “pirates” got transformed into “privateers”, and then into trusted pillars of those empires…

(The banner image at the head here is a representation of Yermak conquering Siberia.)

Pope Gregory introduces new calendar

In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced his scheme for righting a West-European calendaring system (the “Julian” Calendar) that over the centuries had fallen ten days out of sync. His modification reduced the average year from 365.2500 days to a considerably more accurate 365.2425 days (though the “true” length of a tropical year is actually 365.2422 days.)

Under the Julian system, there would be a leap year every fourth year. Under Gregory, and until today, the rule for leap years is:

Every year that is exactly divisible by four is a leap year, except for years that are exactly divisible by 100, but these centurial years are leap years if they are exactly divisible by 400. For example, the years 1700, 1800, and 1900 are not leap years, but the years 1600 and 2000 are.

Gregory’s reform was issued from the Vatican and applied in the small shards of land known as the Papal States. But Philip II of Spain adopted it the same year. In all those areas, in October 1582, the Julian Thursday, 4 October 1582, was followed by Gregorian Friday, 15 October 1582.

It took time for news of this change to reach the distant imperial territories of the (still-emerging) Iberian Union. Many Protestant states were actively resistant to implementing it, seeing it as yet another fiendish Papish plot. “Britain and the British Empire (including the eastern part of what is now the United States) adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Sweden followed in 1753.”

Conquistadoring continues

Lest we forget, here’s just a quick sampling of what was happening in the Spanish Empire this year:

- In April, Hernando de Lerma founded the city of Salta, next to the Arenales River, In today’s Argentina. In his previous endeavor, he had been “Described by historians as a man of violence [who] had problems with several people from the area, including fellow countrymen. Among those he persecuted were the spokesman of a Catholic bishop.” The problems didn’t end. “In 1584, de Lerma was arrested and sentenced to jail in Salta. He appealed, and returned to Spain to take his case to the supreme court, but his appeal was rejected and he was sent to a Spanish jail. While it is known he died in jail, the year in which he died is not known.”

- In Córdoba, Argentina, the conquistadors started building a cathedral, “Our Lady of the Assumption”, which is now the oldest church in continuous service in Argentina.

- On the eastern range of the Andes in the heart of today’s Colombia, the settlement of Sotaquirá was founded on December 20, 1582 by friar Arturo Cabeza de Vaca.

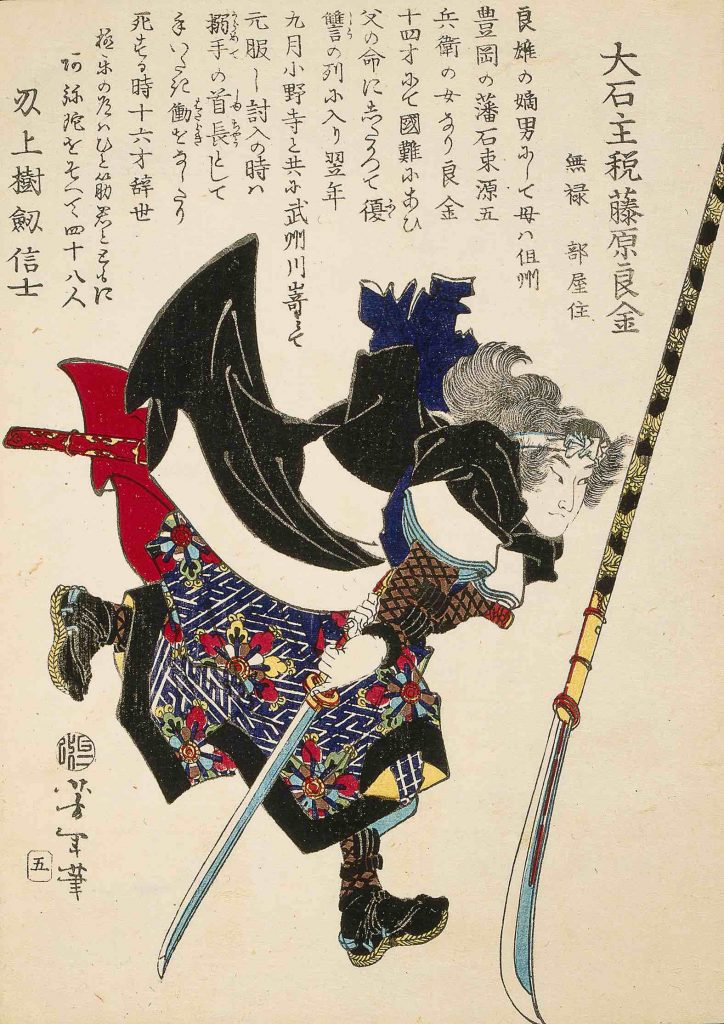

- Over in the Philippines, Spanish-colonial Captain Juan Pablo de Carrión fought a series of land-sea battles in the vicinity of the Cagayan River against wokou pirates who were probably Japanese (possibly led by Japanese pirates.) The battles pitted musketeers, pikemen, rodeleros and sailors against a large group of Japanese and Chinese pirates made up of rōnin [freelance samurai], soldiers, fishermen, and merchants. The pirates had a large junk, and 18 sampans which are flat bottomed, wooden fishing boats. The battles finally resulted in a Spanish victory.