All the usual things were happening in the world of 1574 CE: Mughal Emperor Akbar consolidating his growing territories; Protestants and Catholics contending over broad areas of Europe; Portuguese and Spanish conquistadors doing their transnational thing, and so on. The main development of world-historical importance that year, however, was the Ottoman navy’s final conquest of Tunis, which marked the end of various efforts by Spanish and other Christian-European powers to effect a conquista of North Africa, thus leaving the whole of North Africa– with the exception of two tiny Spanish enclaves in Morocco– to be ruled by Muslim powers.

Then, at the end of 1574, Ottoman Sultan Selim II died and was succeeded by his son Murad III. This post will say a little about that and also about the amazing career of the Ottomans’ star architect and builder, Mimar Sinan, whose masterpiece, the Selimiye Mosque, was completed shortly after the death of the eponymous Selim.

The Conquest of Tunis

Tunis had basically been contested between the Spanish and the Ottomans for several decades. In October 1573– 18 months after his victory over the Ottomans at Lepanto– the Habsburg admiral John of Austria (re-)captured the city and presumably once again set about strengthening its fortifications.

The Ottomans were meanwhile rebuilding their navy– just as Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokullu had vowed would happen… And various Protestant forces battling the Spanish and Habsburgs in northern Europe had reached out to Istanbul to ask the Ottomans to open a second front…

For the Ottoman attack on Tunis, their admirals mustered a fleet of 250-300 warships, with about 75,000 men. (Interestingly, some of these numbers seem to have been derived from the journals of Miguel Cervantes, who– having been ransomed from his earlier capture during the Battle of Lepanto– was now back fighting on the Spanish side.)

Tunis is “protected” on the seaward side by an outer, well-fortified presidio called Goleta. The Ottomans were easily able to impose a maritime siege on Goleta; and John of Austria was unable to send enough ships to challenge them there. English-WP tells us that “The Spanish crown, being heavily involved in the Netherlands and short of funds was unable to help significantly.”

Anyway, the siege and eventual fall of Goleta and Tunis only lasted from July 12 through September 13. “The general of La Goleta, Don Pedro Portocarerro, was taken as a captive to Constantinople, but died on the way. The captured soldiers were employed as slaves on galleys.”

The Ottoman challenge to the Spanish/Habsburgs in Tunis did have the effect of reducing Spain’s pressure on the rebellious Dutch; and in 1582, they established a consulate in Antwerp. But we get ahead of ourselves.

The death of Selim II

Selim (“the Sot”) had never taken much interest in governing, leaving that to Grand Vizier Mehmed Sokollu. Unlike his father (who had died on a battlefield) neither Selim nor the son who succeed him, Murad III, ever made any attempt to lead his troops in battle. Indeed, in Murad’s case, he would never leave Istanbul at all and leave his palace there only very rarely. Clearly, in this case as in the case of several decades’ worth of happenings in the Ming Empire, the survival and wellbeing of the empire depended much more on the effectiveness of a well-developed professional civil-service class than it did on the leadership skills of the “Emperor” himself.

Murad was the eldest of Selim’s seven sons. He’d been born in 1524 and received some early favors and administrative training from his grandfather, Suleiman. One of Murad’s brothers had died in 1572. When Selim died in 1574, that left Murad with five younger brothers. His first act in office was to have them all strangled.

A note on Mimar Sinan

When Selim II died, the “Selimiye” mosque in Adrianople (now Edirne, in Eastern Turkey) was near completion. The renowned architect Mimar Sinan considered this to be his masterpiece– in a total lifetime oeuvre that included Istanbul’s great Suleimaniye Mosque and the following other items:

- 92 other large mosques (camii),

- 57 colleges,

- 52 smaller mosques (mescit),

- 48 bath-houses (hamam).

- 35 palaces (saray),

- 22 mausoleums (türbe),

- 20 caravanserai (kervansaray; han),

- 17 public kitchens (imaret),

- 8 bridges,

- 8 store houses or granaries

- 7 Koranic schools (medrese),

- 6 aqueducts,

- 3 hospitals (darüşşifa)

Sinan had been born around 1488-90, and after 1574 would go on working almost until he died in 1587 or 1588. English-WP tells us this about his life and legacy:

The son of a stonemason, he received a technical education and became a military engineer. He rose rapidly through the ranks to become first an officer and finally a Janissary commander, with the honorific title of ağa. He refined his architectural and engineering skills while on campaign with the Janissaries, becoming expert at constructing fortifications of all kinds, as well as military infrastructure projects, such as roads, bridges and aqueducts. At about the age of fifty, he was appointed as chief royal architect, applying the technical skills he had acquired in the army to the “creation of fine religious buildings” and civic structures of all kinds. He remained in this post for almost fifty years.

His masterpiece is the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne, although his most famous work is the Suleiman Mosque in Istanbul. He headed an extensive governmental department and trained many assistants who, in turn, distinguished themselves… He is considered the greatest architect of the classical period of Ottoman architecture and has been compared to Michelangelo, his contemporary in the West. Michelangelo and his plans for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome were well known in Istanbul, since Leonardo da Vinci and he had been invited, in 1502 and 1505 respectively, by the Sublime Porte to submit plans for a bridge spanning the Golden Horn. Mimar Sinan’s works are among the most influential buildings in history.

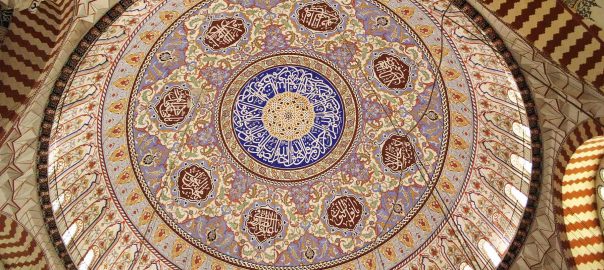

The photo at the head of today’s post shows part of the interior of the dome of the Selimiye Mosque. Here are a couple of other views of it:

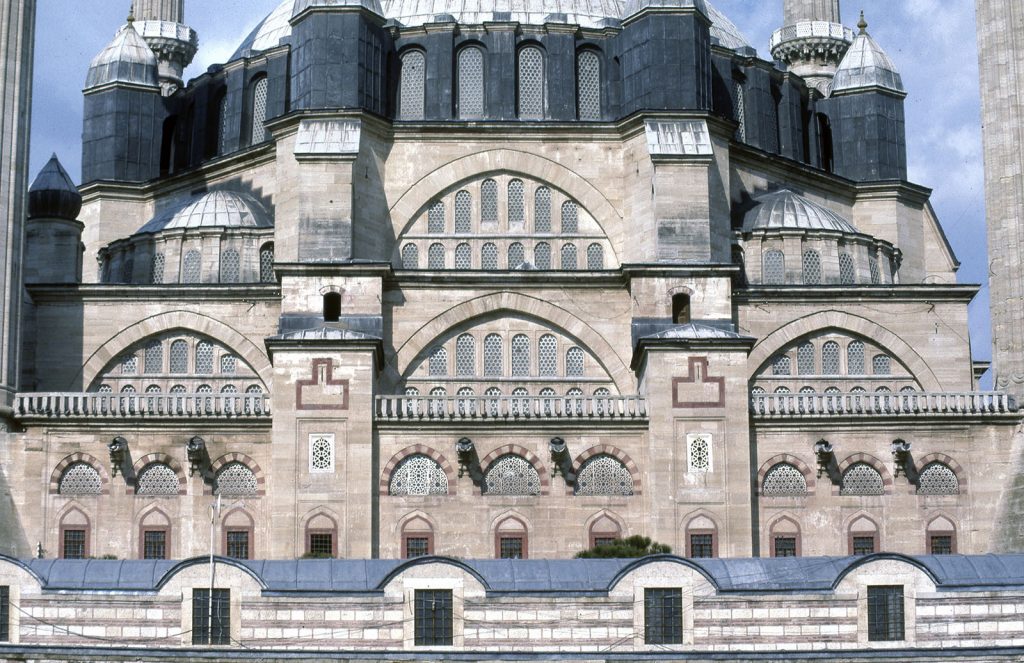

Selimiye Mosque, general view

Selimiye Mosque, South facade