Last year, 1566, one main big thing of world-historical importance happened. This year, 1567 CE, lots of things happened! I shall try to bring order out of a degree of global chaos:

- In China, the Jiajing Emperor dies

- Uproar & uprising in the Spanish Netherlands

- Conquistadores found key settlements in Americas

- Many adventures for Mary Queen of Scots

- Start of 2nd War of Religion in France

- Portuguese expel a French colony from Brazil

In China, the Jiajing Emperor dies

Last year saw the death of Suleiman the Magnificent. Now, in early January 1567, the death of his Ming-Chinese counterpart the 60-year-old Jiajing Emperor is announced. (Though it turns out that, as with Suleiman, the death was kept secret for a while presumably to allow the courtiers to plan for an orderly succession. Thus, it seems the Jiajing E had actually died in December 1566. Oh well. )

The Jiajing Emperor had been in office almost since the start of this project– since 1521.

The manner of his death was pretty hilarious. He has as we know been terrified of death for many years and had ordered numerous procedures undertaken by his court to avert this terrible possibility. One of these was to conscript hundreds of young girls into his court where their menstrual blood was forcibly collected “for his consumption.” There are no details in English-WP on how he consumed it– or, how it was collected. But it must have been an unpleasant procedure for the girls because in 1542 a group of them tried to strangle him. (Their plot was discovered and they were sentenced to death “by slow slicing.”)

I imagine that incident increased his fear of death?

So he then essayed numerous other procedures, including having his courtiers concoct all kinds of herbal and other elixirs– and English-WP speculates it may have been the mercury in some of these elixirs that ended up killing him!

Life in his court must have been a very strange form of existence, for everyone involved. (Had the elixir concocters been acting with intention, I wonder?)

WP gives us a contradictory picture of the Jiajing Emperor’s time in office:

[He] was known to be intelligent and efficient; whilst later he went on strike, and choose not to attend any state meetings, he did not neglect the paperwork and other governmental matters. The Jiajing Emperor was also known to be a cruel and self-aggrandizing emperor and he also chose to reside outside of the Forbidden City in Beijing so he could live in isolation… [He] also abandoned the practice of seeing his ministers altogether from 1539 onwards, and for a period of almost 25 years refused to give official audiences, choosing instead to relay his wishes through eunuchs and officials. Only Yan Song, a few handful of eunuchs and Daoist priests ever saw the emperor. This eventually led to corruption at all levels of the Ming government. However, the Jiajing Emperor was intelligent and managed to control the court.

As we know, throughout his reign the Ming Empire was assailed by Mongols, from the north, and by wokou pirates along much of its east coast. It also saw the horrific Shaanxi earthquake of 1556. The fact that despite all these upsets, and despite the increasing eccentricity of the Emperor himself, the Chinese state continued to function with some degree of continuity seems like a strong testament to the operational capabilities and organizational integrity of the Mandarin class of professional civil servants, which as we have seen continued to conduct fearsome entrance exams and to train and deploy bureaucrats throughout this massive empire regardless of what was happening in Beijing.

The Jiajing had 25 listed consorts, ranging from the four designated as “Empress” down through various different degrees of elevation to one with the title “Imperial Concubine Ning.” These consorts generated 13 recognized children of the Jiajing, of whom Zhu Zaihou, born 1537, and not the eldest prince, was designated the successor upon Jiajing’s death.

Zhu Zaihou was inaugurated as emperor in February 1567, under the imperial name the Longqing Emperor. One of his earliest acts in office, undertaken in 1567 itself, was to revoke the haijin maritime trade ban, and to reinstate foreign trade “with all countries except Japan.”

I imagine the many Portuguese adventurers who had been active in the seas around China for several decades by then, were delighted.

(The banner image above is part of an 85-foot long painting on a silk panel, depicting the Jiajing Emperor traveling with a massive convoy to visit the graves of some relatives. He is riding a black horse here. If you look at the whole thing on Wikimedia you can see elephants in the caravan, too.)

Uproar & uprising in the Spanish Netherlands

In March, a Spanish mercenary army surprised and killed a band of rebels in the Battle of Oosterweel near Antwerp in the Habsburg Netherlands. This launched the Dutch War of Independence, which continued to rage for a further 80 years, though along the way, in 1581, the Dutch were able to establish the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands.

Conquistadores found key settlements in Americas

In January 1567, the conquistador Juan Pardo founded Fort San Juan in the native village of Joara, in pretty far west into the interior of today’s North Carolina. Fort San Juan was the first European settlement in North Carolina and the interior of present-day United States, predating the earliest English settlement at Roanoke Island, North Carolina by 18 years. Pardo planned to use it as an outpost for further expeditions into the interior of what was known to the Spaniards as “la Florida.”, Fort San Juan was the foremost of six forts built and garrisoned by Pardo in modern-day North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee to extend Spain’s effective control deeper into the North American continent.

In 1568, native resisters from Joara and the region surrounding the fort razed this and the five other Spanish forts in this chain, killing all but one of the soldiers therein.

Considerably further south, July 1567 saw the founding by the conquistador Diego de Losada of the settler-city of Santiago de León de Caracas, now more generally known as Caracas (Venezuela.) Earlier Spanish settlements in the region, and even a plantation, had been routed by the natives. But Losada was reportedly able to secure the safety of his new colonial settlement by, “by splitting the natives into different groups to work with, then fighting and defeating each of them.” Surprise, surprise. (Not.)

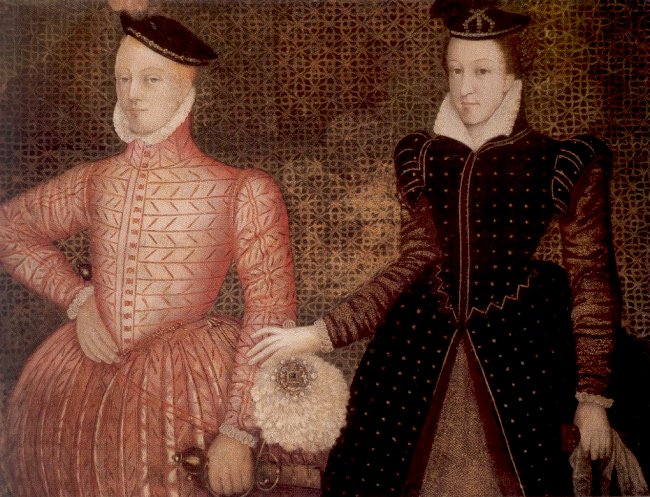

Many adventures for Mary Queen of Scots

Mary, born in 1542, had had a life filled with adventure and intrigue. She inherited the throne of Scotland at just a few days old but was forced to flee to France, where she was raised alongside and at the age of 16 married the Dauphin (Crown Prince) Francis. He inherited the French throne in 1559, and she briefly Queen of France, as his consort. But he died in 1560 and Mary’s mother-in-law Catherine de’ Medici did not want her to stick around as she (Catherine) looked after the French throne for her next son, then ten years old.

In 1561, she met and married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, like her a staunch Catholic. (He had come to France to “extend his condolences” to her after Francis’s death.) They were first cousins, both being grandchildren of England’s long-deceased Henry VIII.

… So in February 1567 we catch up with Mary in Edinburgh, where Darnley has just been murdered, presumably by some of the bands of Protestant lords who were roaming Scotland. (Though he had also fallen out seriously with Mary herself by then; and there was question whether James, the son she had had in Stirling in June 1566, was actually his.)

After the murder of Darnley, another cousin of Mary’s, England’s Queen Elizabeth, wrote her letter that’s a masterpiece of mean-girl spite:

I should ill fulfil the office of a faithful cousin or an affectionate friend if I did not … tell you what all the world is thinking. Men say that, instead of seizing the murderers, you are looking through your fingers while they escape; that you will not seek revenge on those who have done you so much pleasure, as though the deed would never have taken place had not the doers of it been assured of impunity. For myself, I beg you to believe that I would not harbour such a thought.

One of the people on whom suspicion fell in the matter of the murder was a courtier close to Mary, called the Earl of Bothwell. In late April, Mary made one last visit to Stirling to see her child and on her way back to Edinburgh she–

was abducted, willingly or not, by Lord Bothwell and his men and taken to Dunbar Castle, where he may have raped her. On 6 May, Mary and Bothwell returned to Edinburgh. On 15 May… they were married according to Protestant rites. Bothwell and his first wife, Jean Gordon, had divorced twelve days previously. Originally, Mary believed that many nobles supported her marriage, but relations quickly soured between the newly elevated Bothwell (created Duke of Orkney) and his former peers and the marriage proved to be deeply unpopular. Catholics considered the marriage unlawful, since they did not recognise Bothwell’s divorce or the validity of the Protestant service. Both Protestants and Catholics were shocked that Mary should marry the man accused of murdering her husband. The marriage was tempestuous…

Oh gosh, it just goes on and on… Long story short: in late July she was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favor of her one-year-old son, who became King James VI of Scotland.

Start of 2nd War of Religion in France

In late September, Louis, Prince of Condé and Gaspard de Coligny launched a failed attempt to capture King Charles IX and his mother at Meaux, sparking France’s Second War of Religion. The Huguenots captured several cities (including Orléans), and marched on Paris…

Portuguese expel a French colony from Brazil

Back in January 1567, Portuguese forces under the command of Estácio de Sá had finally driven French colonists out of an settlement they’d originally built at Uruçú-mirim in Rio de Janeiro, in 1555. De Sá was hit in the eye with an arrow and died shortly after.