A large part of the international-affairs commentatoriat in the United States is opining on the issue of a possible “Cold War 2.0” with China. Some are warning it may come unless we do X, Y, or Z. Some are saying it is already here. Some are cheering it on. Some are “judiciously” saying it may only be Cold War 1.5… And so on..

I think they’re all barking up the wrong tree– quite possibly in completely the wrong forest. (And/or, some of them may be just barking mad… But that’s another topic.)

A “Cold War” implies there are two major powers (or blocs of powers) that are strongly opposed to each other but feel constrained from engaging in an actual, military “hot” war against each other, resorting instead to broad “indirect” campaigns to contain and whittle away at each other’s power in non-military ways– or sometimes, in military ways but on distant, third-country battlegrounds. (This Wikipedia entry credits George Orwell with having introduced the term “cold war” to the English-language lexicon, in articles from October 1945 and March 1946 in which he accused Russia of waging a “cold war” on its neighbors. In February 1946, U.S. diplomat George Kennan sent the Long Telegram from Moscow in which he urged Washington to focus on “containing” Soviet power.)

You could say the historic Cold War (version 1.0) was set in motion when the two armies, the American and the Soviet, engaged in their last frantic race for Berlin in Spring 1945. And its momentum really got a boost that August when Pres. Truman, having refused an initial Japanese offer of surrender, ordered the dropping of the United States’ two prototype atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in what was widely understood to be a live “demonstration” to Stalin of the fearsome new power at Washington’s disposal. The dropping of those bombs inaugurated a completely new period in world affairs: one in which nuclear weapons and the terrible consequences of their use were a proven reality; in which the United States stood astride the globe, unmatched in either military or economic power… oh, and there was also, for the 45 years that followed, a simmering Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

In 1990-91, the Soviet system of government succumbed to its long-acting sclerosis, and collapsed completely. There was no longer any Cold War; and thank God, there had never been an actual Hot War between the two nuclear-armed “superpowers”– though numerous countries in the Global South had been devastated by the proxy wars the superpowers had displaced onto them.

But there was still, more evidently than ever before, American power. After 1991, the United States stood unmatched, hegemonically, on the world stage. That was nearly 30 years ago. According to several indicators of national strength, in recent years its performance (and rankings) started noticeably to lag. Then came the coronavirus, which as of now has certifiably killed 92,645 Americans, and mounting, for a death rate of 28.1 per 100,000 people. (In China, the comparable death rate is 0.33 deaths per 100,000.)

Umair Haque wrote recently:

There are still about 1000 deaths per day in America. At the pinnacle of the pandemic, there were about 1500. Reopening the economy now will probably push the death rate back up towards that number, or higher. 1500 deaths per day times 30 days is 45,000 in a month. Another 90,000 in two months. We’re already at 90,000, expecting 200,000 as the pandemic slows — but it’s not going to now. You can see how quickly the numbers become apocalyptic.

The only reference we really have for such numbers is if a nuclear bomb was dropped on America.

He is right. The total death tolls for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is estimated at 225,00. And those were not instantaneous. As John Hershey and others have documented, many of those deaths took place over the months that followed August 1945.

Haque’s warning that re-opening the U.S. economy will now likely push the death rate to increase once again has been echoed by numerous epidemiologists and other specialists. The economic losses in the United States have already been staggering. And the re-openings we’re now starting to see are as ill-planned, patchy, and poorly enforced as the (very partial) lockdown that preceded it. This almost guarantees that the country will continue to be mired in the linked evils of disease, economic distress, fear, and distrust for many months into the future. And another component of an effective response: social and political trust, which is a key aspect of effective leadership and effective action in any crisis as massive as this one. Here in the United States, the degree of active distrust at nearly every level is alarming.

And China?

Earlier this month, Politico’s David Wertime wrote:

As coronavirus has spread outward from its Wuhan origins, the Chinese government has worked hard to spin an initial embarrassment into a win for its international image, with mixed success. But to Chinese authorities, the audience at home is the one that really matters, and among that vast cohort, the verdict is unsparing: China has outperformed, while America has disastrously faltered. It’s a sentiment shared by even educated, internationalized Chinese observers — the very group once inclined to look to America as an exemplar.

More recently, venture capitalist and political scientist Eric Li, a resident of Shanghai, took to Foreign Policy to share his list of the five things he had learned about China’s society and government from what he saw during the crisis there (which he said looked as if it might have been ended):

- The Chinese people trust their political institutions.

- Chinese civil society is alive and well.

- In China, state capacity counts even more than the market.

- The party has played the central role.

- Chinese President Xi Jinping is a “good emperor.”

Both those articles are well worth reading– as is this earlier, detailed description of what the Chinese authorities did to identify, contain, and roll back the virus.

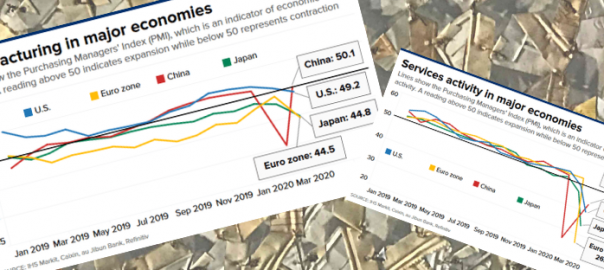

The bottom line is this. Americans in and out of government can strut, bluster, and threaten “retaliation” against China as much as they want. But China and a number of other countries, primarily in East Asia, have almost completely vanquished the virus. China was already able in April to show a significant bounce-back of manufacturing (as shown in the red “V” lines in the charts above) and has a credible-looking “New Deal”-type plan in the works to bolster continued recovery. And the Chinese political system seems to enjoy significant levels of trust from its citizens… Meantime, Americans can see no way out of the disease, economic distress, fear, and distrust that so deeply bedevil our country.

Who’s the credible superpower now?

This is why I don’t see the talk about a possible “Cold War 2.0” as meaningful or relevant. If there were to be any sort of “cold war” between the United States and China, then U.S. policymakers would still be able credibly to start planning how to manage this complex relationship with China. But in reality, the options for “managing” the core of this relationship are pitifully few, since the central task of whatever U.S. leadership emerges from this Covid nightmare will be to manage the precipitous collapse of the globe-circling empire the United States has sat atop of since 1945.

This is no easy task. Big accommodations have to be made. I know. I grew up in the United Kingdom when the central foreign-policy task of all of our governments, whether Tory or Labour, was to manage Great Britain’s imperial decline. (Though we did at least score a National Health Service out of the process: A wondrously good bargain, as Boris Johnson has recently been rushing to attest.)

So here in Washington in Spring of 2020, I say, Let ’em huff and puff with their new flatulations of childish Sinophobia. Let them threaten this or that version of a new “Cold War”. Let them compete in elections– if these are to be held– on versions of “Who can be tougher on China.” But the cold reality shows that, as Banquo said, “It is a tale, told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

(And in this situation, just about all of the military machine the United States’ vast phalanxes of military-industrial lobbyists have forced taxpayers to pay for signifies nothing, too. That is another part of the story that also deserves to be told.)