For legitimate international aid organizations, the intense needs of the three million or so residents of Syria’s war-torn Idlib province pose a sharp moral (as well as legal) dilemma, since the many very needy noncombatants there have effectively been held hostage for more than two years by the genocidal coalition of militias led by the Al-Qaeda-affiliated Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS.) Because of its control over the civilian population–including those who are “indigenous” to the region, those who came from elsewhere in Syria, and those who are family members of the many foreign fighters who have also flocked here over recent years–the HTS has been able to manipulate aid flows and use the aid goods to give it additional leverage over the local population.

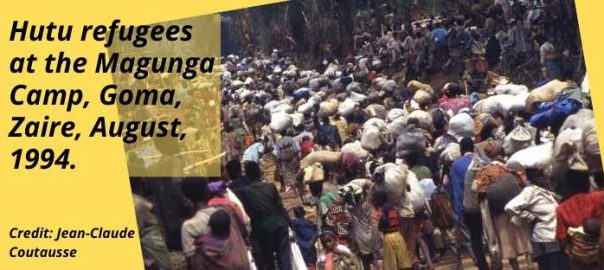

In a piece I published here earlier this month, I cited and provided links to some sources that have followed this heartwrenching issue very closely, including this 2017 piece by Aron Lund and this 2018 piece by the Long War Journal‘s Thomas Joscelyn. I also noted that this was not the first time international aid organizations had faced the dilemma of how to provide aid to needy civilians held captive by an actively genocidal organization, noting that big international aid orgs had faced exactly this same dilemma when responding to the massive inflow of Rwandan-Hutu refugees into eastern Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) in the summer of 1994. Those refugees had fled their home communities inside Rwanda at the urging of the genocidal “Interahamwe” militia network that had been largely responsible for the terrible, 100-day-long anti-Tutsi genocide of April-July 1994.

In this blog post, I will share some of an ongoing project I am working on, in which I consider the similarities and differences between the “Interahamwe aid trap” the legit aid orgs faced back in 1994 and the (very similar) “HTS aid trap” they face in Idlib today. I will also look at how that dilemma got resolved in 1996 or so, and the lessons we might take from that, today.

My key source for the following analysis of the similarities and differences between the two situations is the chapter “Hard Choices after Genocide: Human Rights and Political failures in Rwanda” that Ian Martin contributed to Jonathan Moore’s excellent 1998 volume, Hard Choices: Moral Dilemmas in Humanitarian Intervention.

- What is the population that needs aid and how did it get to its present location?

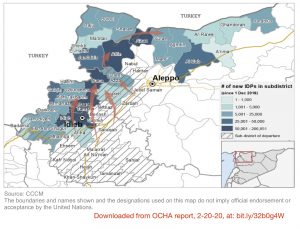

In Idlib and some slivers of adjoining Syrian provinces today, the population that needs aid is a large portion of the area’s currently 2.5 million to three million population, which has suffered greatly from civil strife since 2011-12. This population is held under the sway of HTS and its allies, comprising some takfiri fighters who are indigenous to the region, some from elsewhere in Syria, and some who are non-Syrians. Many of the fighters now in the region, and a portion of the civilian population, came to Idlib from other parts of Syria during the past three years, as a result of the Russian-negotiated agreements the Syrian government concluded with fighters in areas that came back under central government control, which allowed any fighters and noncombatants who did not want to live under central government control to be bussed to Idlib.

In Idlib and some slivers of adjoining Syrian provinces today, the population that needs aid is a large portion of the area’s currently 2.5 million to three million population, which has suffered greatly from civil strife since 2011-12. This population is held under the sway of HTS and its allies, comprising some takfiri fighters who are indigenous to the region, some from elsewhere in Syria, and some who are non-Syrians. Many of the fighters now in the region, and a portion of the civilian population, came to Idlib from other parts of Syria during the past three years, as a result of the Russian-negotiated agreements the Syrian government concluded with fighters in areas that came back under central government control, which allowed any fighters and noncombatants who did not want to live under central government control to be bussed to Idlib.

In eastern Congo/Zaire, in1994, the largest influx of Rwandan-Hutu fighters and civilians occurred within just five days in mid-July 1994 as the previously Hutu-controlled central government in Rwanda collapsed and fighters loyal to the Tutsi-dominated Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) seized control in the capital, Kigali. The previous central government in Kigali had been deeply implicated in the organization and execution of the brutal, 100-day-long anti-Tutsi genocide, acting in coordination with many local-government bodies and a shadowy militia called the Interahamwe. The 850,000 Hutus who fled to the northern part of the eastern-Zaire province of Kivu in July 1994 included many members of those governmental and Interahamwe networks. (In roughly that same period, some 500,000 Hutus crossed into Tanzania and 650,000 into southern Kivu and neighboring Burundi.)

Martin wrote (p.159-160),

The exodus can be characterized as a politically ordered evacuation… The [Hutu] administrative authorities sought to induce their populations to flee, warning them of massacres if they awaited the arrival of the [RPF], and there are reports of those refusing to leave being killed by the militia…

This is not to deny, however, that many, probably most, left of their own volition and in real fear of the RPF advance. Nor was that fear without any justification… Reprisal killings [by the RPF] occurred, in some cases amounting to massacres.”

Thus, in both cases, there were large-scale movements of population, conducted in the context of hostilities. In Idlib, there were a number of such successive evacuations, compared with just single big one in Rwanda-Kivu. The evacuations to Idlib were much smaller in scale than the massive Rwanda-Kivu flight, and they did not constitute a cross-border flight, such as would have prompted the intervention of the UN’s High Commission Refugees (UNHCR). The Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Idlib currently constitute somewhere under half of the area’s total population. In many parts of Kivu, the arriving Rwandan Hutus massively outnumbered the local population; but because the Rwandan Hutus had crossed an international border the civilians among them did qualify for UNHCR services.

In both cases, the cross-“front-line” hostilities continued even after the evacuations. In the Rwanda-Kivu case, the Interahamwe continued to launch cross-border raids against RPF and civilian-Tutsi targets inside Rwanda; and the RPF also on occasions fought the Interahamwe (though the thinly-stretched RPF was also working hard to exert and protect its control of all of Rwanda.)

- What was the situation of the refugee camps in Zaire?

In mid-1994 the UNHCR and various international aid organizations set out to provide the normal range of basic humanitarian services to the new waves of Rwandan refugees in Zaire and elsewhere. This included providing basic shelter, sanitation, and food aid for them. These tasks were complicated by a number of factors, including:

- A large-scale cholera outbreak in the refugee camps

- The control that the recently deposed Rwandan-Hutu administrative officials and Interahamwe were able to exert over the refugee population

- The remoteness of Kivu from most transportation/logistics hubs, and

- The interaction between the arrival of these refugees and existing social/political cleavages among Kivu’s native population(s).

On the second of those points, Martin wrote (pp.160-61):

The former leaders kept almost total control of the population in the camps. The U.N. secretary-general reported in November 1994 that about 230 Rwandese political leaders were in Zaire, exerting a hold on refugees through intimidation and the support of military personnel and militia members in the camps. The militia resorted openly to intimidation and force to stop refugees who were inclined to return to Rwanda…

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working in the Zaire camps were even franker. Former Rwandese authorities controlled almost all aspects of camp life, they reported, and used the distribution of relief items to reinforce their position. Refugees were being threatened, attacked, and killed for being “RPF spies” or for wanting to return to Rwanda: the militia carried out summary executions, public stoning, and other physical violence.

In Kivu, the existence of cholera lent huge, and quite understandable, urgency to the aid efforts. In Idlib, there has not been any large-scale cholera outbreak (so far.) However, if the fear of cholera erupting out of the refugee population into the general population in Zaire– and also affecting the aid workers themselves– lent a sense of broader threat to the actions of the aid orgs in 1994, today it is more the very present threat of a massive outflow of refugees from Idlib into– and through– Turkey that sharpens the dilemmas faced by the international aid orgs. Add to this the fact that many of those who might seek to escape Idlib in such an outflow would also be either some of the numerous foreign jihadis who have been active in Idlib, or members of their families.

But all the other factors listed above have been mirrored in some way in Idlib. Regarding the intimidation and control the genocidal fighting groups have been able to exert over the noncombatant population, there is a direct parallel. Regarding ease of access to the outside world by the civilian population that is effectively held hostage by the fighters, people in Idlib perhaps have a little more ability to contact the outside world than Rwandan refugees had in Kivu in 1994-96—but that contact all has to be conducted through Turkey, which has its own strong political agenda in Idlib and the rest of Syria. Aid groups also have to keep on good terms with Turkey if they want to be able to send aid goods into Idlib.

Regarding the interaction between the IDP population in Idlib and the local populace, much too little is known. But the distribution by various takfiri groups of gruesome snuff videos glorifying atrocities against members of various indigenous church communities indicates that the arrival of the IDPs may well have intensified hostilities among the different religious groups inside Idlib.

- How did the UN try to reduce the control the genocidaire networks in Zaire exerted over the civilian population?

The UN secretary-general’s first proposal for doing this was to find a way to “separate out the former political leaders, military and militia, as well as to maintain security in the camps.” (p.161.) This was a fine idea. But it went nowhere because it was estimated that a peacekeeping force of 10,000-12,000 would be needed, and the UN was unable even to raise a force of 3,000-5,000 envisaged for a less ambitious mandate. The Security Council then handed the challenge over to UNHCR, which contracted with the host government (Zaire) to pay for Zaire “to provide a contingent of elite troops, with international trainers.”

On this basis, Martin wrote,

A reasonable degree of security in the camps was achieved, but without the control of the former Rwandan authorities being broken. Moreover, the Zairian Security Contingent had neither the will nor the capacity to stop the flow of arms, military training, and cross-border incursions into Rwanda.

He noted that in these circumstances, MSF-France and the International Rescue Committee withdrew from the camps in late 1994. By August 1995, MSF-Belgium and MSF-Holland had also pulled out.

In Idlib, the genocidal takfiris of HTS have not always enjoyed the same monopoly of control over the civilian population that the Rwandan-Hutu genocidaires enjoyed over their captive populations in Kivu, 1994-96. For a while after the anti-Asad forces in Syria seized control of Idlib’s capital city in 2015, there was also a significant presence of non-Al-Qaeda oppositionists in their ranks, including the US- and French-back “Free Syrian Army (FSA)” and the Turkish-backed Ahrar al-Sham. But over the summer of 2017, HTS (formerly known as the Jabhat al-Nusra) consolidated its control over most of the area, including over the two key crossing points into Turkey and the internal financial system. (Some details of this can be found in this piece by Sam Heller.)

Western governments and the relief organizations associated with them (including US government-funded NGOs like Mercy Corps, the International Rescue Committee, and the Syrian American Medical Society) have faced numerous dilemmas in addressing the humanitarian situation in Idlib. HTS is still on the US government’s list of terrorist organizations, and the non-HTS organizations with which US aid organizations used to work have all now either dissolved or become subsumed under HTS’s governance umbrella.

The taxonomy of the aid organizations active in Idlib is significantly different than the ones active in Kivu. In Kivu, and in the other areas to which Rwandan Hutus fled after July 1994, they were generally (though with one notable exception) fleeing across an international border. Hence, the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) was the lead organization providing aid. In Idlib, the people fleeing or being evacuated have not crossed an international border. (Indeed, they’re being prevented by Turkey from crossing into Turkey.) Hence, they do not come under the purview of UNHCR.

Without the UNHCR to play the lead role coordinating international aid, a patchwork of other organizations has been doing so. These include:

- A patchwork of other UN agencies such as the World Food Program, UNICEF, etc.

- Turkish aid organizations, such as IHH.

- Aid organizations supported and funded by other Muslim governments or non-governmental networks (often GCC-based.)

- Big U.S.-based organizations like the International Rescue Committee and Mercy Corps, both of which have in recent years received a majority of their funding directly from U.S. government agencies. This means they may be more accurately described (in the British parlance) as QUANGO’s– quasi-governmental NGO’s– rather than as straight-up, supported-by-the-public NGO’s. In other words, they are fronts or delivery mechanisms for US government funding. You can read my September 2018 analysis of the IRC here.

- Other sizeable US or international organizations such as Medecins sans frontieres or Physicians for Human Rights.

- Specialized and highly politicized Syrian-diaspora-created NGOs like the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS), Violet, etc. These organizations all have a strongly partisan, anti-Assad ideology that completely obliterates the longstanding norm that there should be a politically neutral “humanitarian space” in which legitimate humanitarian-aid organizations can work together and across political front-lines.

- Specialized and highly politicized “aid” organizations created by the intelligence arms of the UK government and other Western governments. Prime among these is the Syrian Civil Defense/”White Helmets.” The project to create and support the White Helmets paralleled (and in many cases intersected with) the UK government’s project to create and support partisan “citizen journalist” networks as an integral part of its anti-Assad “information ops” project.

The credibility among Western publics of the kinds of aid organizations described in ## 4-7 above has meant they have been subjected to very little scrutiny of the circumstances in which they’ve been operating The attitude has generally been one of, “Oh, if the IRC says the Syrian military have been bombing hospitals and says nothing about the presence of armed jihadis on the ground in Idlib, then that must be true!” But this kind of glib acceptance of what the IRC or SAMS or the White Helmets might report ignores the fact that any representative of one of those organizations who is actually operating on the ground inside Idlib is completely aware of the fact that she or he is doing so under the thumb of the jihadis and at their sufferance.

When the UNHCR was facing the many challenges it faced in Kivu, 1994-96, it knew that (at least in theory) there was a national Zairian government and a national Zairian army with which it could coordinate to work to establish some sense of order in the camps, though that was always, as Martin acknowledged, pretty partial and problematic. But in Idlib, if the aid organizations wanted to “separate” the needy civilian IDPs from the genocidal forces who are controlling them, how could they even start?

4. How was the dilemma the aid organizations faced in Kivu eventually resolved?

It finally got resolved, in 1996-97, when the Rwandan army, now firmly under the control of the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), launched a large-scale– and very rights-abusing– military campaign deep into Zaire, forcing the Interahamwe to disband and bringing most of the Interahamwe’s former civilian hostages home to Rwanda.

As I had noted here, that RPF military campaign into Zaire also helped topple the country’s long-time dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko. And the intense internal woes inside the massive country of Zaire– now, the DRC– have certainly continued since then.

The situation of the Rwandan-Hutu refugees forcibly repatriated to their home communities by the Rwandan government in 1996-97– like that of the many Hutus who had never left Rwanda–was for many years a very difficult one. Immediately after the RPF’s military captured Kigali and brought an end to the genocide, it started locking up suspected participants in the genocide. The number of those incarcerated in filthy prisons, jails, and lockups rapidly exceeded 100,000, from a total national population of some seven million. In 1996, the Catholic priest and rights activist Andre Sibomana wrote this about a visit he had made to one of the prisons in 1995:

There were three layers of prisoners: at the bottom, lying on the ground, there were the dead, rotting on the muddy floor of the prison. Just above them, crouched down, there were the sick, the wounded, those whose strength had drained away… Finally, at the top, standing up, there were those who were still healthy. They were standing straight and moving from one foot to the other, half asleep… I remember a man who was standing on his shins: his feet had rotted away.”(pp.108-109.)

Of the returning Hutus, many found that their homes, lands, and livestock had been taken over by Tutsis who had returned with the RPF in 1994 from their lengthy long political exile in other countries, mainly Uganda. Many also found themselves under suspicion of having participated in the 1994 genocide. Gradually, generous international aid to post-genocide Rwanda allowed the government to improve both the situation inside its prisons and the way it handled accusations of involvement in the genocide.

In Idlib, the best prospect for separating the mass of noncombatant residents of the enclave from the well-armed Al-Qaeda affiliates who currently hold sway over them would be if the intermittent negotiations over the Idlib issue among the Syrian, Turkish, and Russian government could be brought to a successful conclusion. Realistically, in this part of Syria, this means successful negotiations between Turkey and Russia (which controls most of the airspace over Idlib, from its airbase at Hmeimim.) For both those parties, Idlib– and indeed, the whole of the Syrian issue– is only a small part of a much broader bilateral agenda. Thus for now, it does not seem imminent that negotiations will succeed– though there have been some indications that political pressure within Turkey may soon start to push President Erdogan to make more concessions to Syria’s President Assad, including over Idlib, than he has thus far been prepared to make.

Until the current, extremely anguished situation inside Idlib can be resolved, the enclave’s residents and those seeking to send aid to them will therefore continue to be caught in their own version of the deadly “Interahamwe aid trap.”