Almost from the beginning of the US-supported regime-change project in Syria, US policymakers have incorporated several kinds of planning for what is called “transitional justice” into their pursuit of the project. Transitional justice (TJ) is a field that came into great vogue in the mid-1990s, after two key developments in the post-Soviet world: (1) the UN Security Council’s creation of a special International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and (2) the agreement of the African National Congress in South Africa to negotiate an end to the Apartheid system– but with the proviso that the most heinous of the rights violators of the Apartheid era all ‘fess up to all their actions in a specially created Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC); and if those confessions were deemed full and heartfelt, then the perpetrators could escape prosecution for their actions.

From the early 1990s, these two approaches to TJ were in tension with each other; and that tension has lain at the heart of the rapidly burgeoning field of TJ projects ever since.

For its part, the prosecutorial/criminal-justice approach claimed descent from, crucially, the two US-dominated international courts established immediately after WW-II, in Nuremberg, and Tokyo. (The above photo is of Herman Goering on the stand, in Nuremberg.) The creation of ICTY was followed, two years later, by the Security Council’s creation of a parallel special court for Rwanda; and meantime, a broad movement emerged to press for the establishment by treaty among nations of a permanent “International Criminal Court” (ICC) which could hold accountable perpetrators of the worst forms of atrocities– described as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide– in a criminal proceeding. In 1998, 120 governments adopted the “Rome Treaty” that established and set the rules for this court. In 2002, the requisite 60 countries had ratified the Rome Treaty and the ICC came into existence, headquartered in The Hague.

I have reflected at length in many earlier writings (including this 2006 book and these earlier articles: 1, 2) on some of the shortcomings of the ICC and the criminal-justice approach it adopts to dealing with the aftermath of atrocities. Suffice it here to note the following:

- The United States is not a member of the ICC; but all the presidents since 2002 have on occasion sought to use the investigative, international arrest, and prosecutorial powers of the ICC, or to threaten their use, against political figures around the world they are opposed to.

- The whole prosecutions movement since the creation of ICTY has claimed descent (and therefore a strong degree of legitimacy) from the whole Nuremberg/Tokyo Trials legacy. But all the “modern” international courts have omitted from their actual charge-sheets one of the key acts– perhaps the key act– prosecuted at Nuremberg and Tokyo: the crime of aggression, that is, the act of launching an aggressive war. The Rome Treaty listed the crime of aggression as potentially on the ICC’s docket, but its signatories have failed to reach agreement on how to define it and thus it has not in practice been chargeable.

- In March 2003, eight months after the ICC formally came into existence, the United States launched a massive, quite unjustified (and militarily successful) war of regime change in Iraq– a war that UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan later admitted lacked any legitimacy.

- One of the early acts of the “Coalition Provisional Authority” through which the US military ruled Iraq after the invasion was to establish a special tribunal to try former president Saddam Hussein and his top associates. After the CPA set up an Iraqi government (though still under its own control), this government adopted the trial plan, renaming the body the Supreme Iraqi Criminal Tribunal. Saddam was captured by US soldiers in late 2003 and sent for trial by the SICT; in November 2006, it sentenced him to death. He was held in a prison inside the US military’s “Camp Justice.” On December 30, 2006 he was taken to a scaffold earlier than the Americans had planned by a group that included SICT officials and members of Shiite militias. There, he was hanged to the jubilation of many of the witnesses, who also circulated cellphone videos of the event. Saddam’s very unseemly execution capped off a trial that had been marred throughout by grave irregularities.

This political background should be borne in mind when considering the legitimacy (or even, the utility) of any plans to use prosecutorial TJ mechanisms in connection with US-led regime-change projects in the present era– in Syria, Venezuela, or anywhere else.

In June 2019, Max Blumenthal and Ben Norton published a broad and detailed description in The Grayzone of the work of several organizations that have as their mission the collection of evidence of war crimes and other atrocities committed in Syria and to some extent also Iraq, and the compilation of this evidence into forms that can help (or even spur) the prosecution of alleged perpetrators by international courts.

Most of these organizations are funded by Western governments. Most were also, like the Syrian Network for Human Rights, founded at, or shortly after, the time that Secretary of State Hillary of Clinton and Pres. Barack Obama committed Washington to full support of the regime-change project in Syria. Other such organizations include:

- the “Commission for International Justice and Accountability”, an organization founded by an enterprising Canadian investigator called Bill Wiley, that has received funding from Canada, the EU, numerous European countries, and the United States. CIJA got a massive boost in visibility in the United States after the New Yorker published a serious of materials about it written by Ben Taub. In this one, Taub breathlessly described how, “At an undisclosed location in Western Europe, a group called the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) is gathering evidence of war crimes perpetrated by the Syrian government… “

- The Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC), which states explicitly on its website that it was founded in 2012 by the “Group of Friends of the Syrian People”– that is, the coalition of governments united in their project to overthrow the Syruian government. On its website, SJAC states that it was founded in The Hague and moved in 2016 to Washington DC, where it “is currently registered as a nonprofit corporation.” However, no organization of its name comes up in standard searches of nonprofits, while SJAC is currently listed as a project of the old cold-war organization, IREX.

During their early years in existence, these organizations had as their goal the collection, preservation, and organization of materials that could, after the opposition’s overthrow of the government, serve in a war-crimes court as evidence of the organization by Syrian government officials of broad patterns of gross abuse.

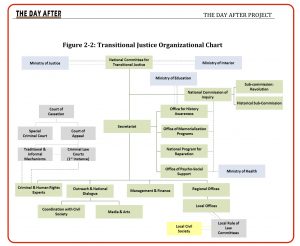

The work of these documentation organizations was also inspired by “The Day After Project”, a project the federally funded U.S. Institute of Peace launched in late 2011 to plan for what decisionmakers in Washington all confidently expected would be the imminent fall of the Assad government. The Day After Project’s final report (PDF) was launched in August 2012, ostensibly by the all-Syrian group of 45 individuals who co-authored it. It contained a lengthy section on “Transitional Justice”, complete with a complex organogram showing how all the proposed parts of this project should be managed.

That was still the heyday of the thinking in official Washington that “Assad will fall any day now!” Washington– like Paris, Ankara, Doha, and other anti-Assad capitals– was full of very busy, Ahmad Chalabi-style Syrian exiles (often being handsomely paid by their Qatari, Saudi, or Emirati backers) who had managed to persuade themselves and numerous “locals” in those Western countries that any day now they would be riding into Damascus to take over the whole Syrian government. Well, in March 2003, Ahmad Chalabi did at least manage to get back to Baghdad in the wake of the US invasion of the country– though once he arrived, it was patently clear he had never enjoyed anything like the degree of popular backing within Iraqi society that he had long claimed to have. Regarding Syria, the earnest bands of exiles who were making detailed plans for their own imminent return “home” never even made it. They were unable to persuade a US government and public that had already been badly duped once, back in 2003, that the claimed “sins” of the Syrian government were bad enough to warrant a full-scale U.S. invasion– especially one that this time around (unlike in 2003) threatened to trigger a serious global showdown with a now more confident and capable Russia.

Yes, under Obama and Clinton, Washington did give the anti-Assad fighters some serious shipments of arms, along with strong political backing; and they and the Israelis did from time to time launch one-off strikes against Syrian military bases. But Obama and Clinton never signed off on a full-throated military campaign against Assad; and the anti-Assad rebels proved quite incapable of actually persuading enough Syrians to come over to their side, to win. The sides settled into a very lengthy and draining stalemate, during which the government side slowly proved able– with the help from international allies on whom it was quite legitimately able to call– to retake parts of Syria that had earlier been taken over by the foreign-armed (and increasingly jihadi-controlled) rebels.

Today, nine years into the conflict in Syria, there is no hope at all of the opposition seizing Damascus. And within the anti-Assad camp itself, extremist jihadis affiliated with either ISIS or Al-Qaeda long ago took over control, snuffing out the hopes of the Washington establishment that “moderate rebels” of the kind now firmly ensconced in Western think-tanks can ever become a significant force inside Syria. All the plans that those “moderate rebels” had made for the imminent establishment of an anti-Assad “special war-crimes court” like the one that earlier tried Saddam Hussein, or for other mechanisms of post-victory “transitional justice”, have to them a quality that is either robotic or slightly other-worldly.

Last week I went to the launch at a Qatari-funded think-tank called the Arab Center of Washington of a book called Accountability in Syria: Achieving Transitional Justice in a Postconflict Society. I guess the Qatari funding has been running a bit low, because there were no free copies of the book being handed out, and only one sample copy that attendees could take a glance at. It costs $90. Rush right over to the link above to buy your copy!

Last week I went to the launch at a Qatari-funded think-tank called the Arab Center of Washington of a book called Accountability in Syria: Achieving Transitional Justice in a Postconflict Society. I guess the Qatari funding has been running a bit low, because there were no free copies of the book being handed out, and only one sample copy that attendees could take a glance at. It costs $90. Rush right over to the link above to buy your copy!

The three panelists were: the book’s editor, Radwan Ziadeh, a longtime regime-change advocate whose only listed professional achievement is his longtime gig as a “Senior Fellow” at the Arab Center; Mai el-Saadany, a US-trained Syrian-American lawyer who now works at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy; and Mohammed Alaa Ghanem, who until recently was Government Relations Director and Senior Political Adviser for the Syrian American Council, one of Washington DC’s principal regime-change organizations. Ghanem, who still has a (presumably nicely funded) affiliation with the UAE-funded Atlantic Council, is now doing a Master’s degree in international affairs at Columbia.

At one level, it was kind of a sad event. When Ziadeh started talking, he recounted that work on the book had started back in 2015– at a time when it may have been possible for regime-change advocates still to imagine that one day soon, just possibly, they could seize power in Damascus. (Hence, the reference in the book’s sub-title to a “Postconflict society.”) Poignantly, he spoke about how back then, “Aleppo”–actually, just that small portion of East Aleppo that the opposition still controlled– was becoming a center of evacuation, and how Ma’aret al-Numaan, in the opposition fighters’ Idlib redoubt, was a center of evacuation today.

In both instances, as the government regained control of terrain previously held by the jihadi extremists, the government allowed the opposition fighters and any civilians who chose to leave, to do so, and indeed, facilitated their departure. This is in notable contrast to the bloodthirsty actions the jihadi oppositionists have always taken toward the residents and defenders of areas that they’ve overtaken. But the video footage of desperate civilians fleeing in advance of the Syrian army’s arrival always looks pretty heart-wrenching.

(The videos widely circulated in the west notably do not depict the civilians who stay in the areas being brought back under Syrian government control– or, the earlier presence and activities of any of the jihadi fighters, some of whom who are Syrian and many of whom are not, who had controlled these areas so brutally over the preceding few years.)

When Mai el-Saadany spoke she stated confidently that, “The time for justice is now… We can’t afford to wait until the conflict ends.” She said that both the International Criminal Court and the UN’s doctrine of “Responsibility To Protect” (R2P) had proven useless in protecting Syria’s people; but that even without those tools there were three “accountability tools” the Syrian oppositionists could use: Documentation; a couple of different UN inquiry/documentation mechanisms; and prosecutions outside Syria, such as the one brought against two former Syrian officials by a court in Germany, last October.

When she talked about documentation, el-Saadany singled out for special praise the efforts of a group called Bellingcat–and of The New York Times.

For his part, Ghanem focused on the contribution he had made to the Accountability in Syria book, in which he looked at what he described as the “sectarian cleansing” that he saw the Syrian government as undertaking in formerly opposition-held areas over which it regained control. He accused “the Assad regime” of being dominated by Alawites and of engaging in “sectarian cleansing or demographic engineering” against “communities” in these areas, though he did not name these “communities.” He said he had been very proud to have gotten reference to this phenomenon included in the “Caesar Act”— a US sanctions measure against Syria that was signed into law in late December.

The most interesting part of this sad gathering came toward the end ( at 1h24m on the video.) A questioner had asked how the panelists thought that the kinds of “accountability”mechanisms they favored could be applied to other perpetrators of atrocities in Syria, “such as in the Turkish-controlled areas, or the SDF”, in addition to the government. At that point, Ziadeh almost completely lost it. The other two panelists, much better qualified and better prepared professionals than he, had both expressed their support for the idea that all accused perpetrators of significant atrocities, whatever their political alignment, should be subjected to the same accountability measures. (This is, after all, a key tenet to the whole field of transitional justice… Heck, in South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, even some of the excesses of the ANC came under the same kind of scrutiny as the gross tortures of the Apartheid regime.)

Ziadeh argued that only the “Assad regime” should be addressed by any accountability mechanisms. “The Syrian government– it became not a rogue state, but deep sectarian militias, that has no regard for the life of any Syrian” he said. “It’s impossible to think of having a political settlement with this kind of militia in control of Syria… What’s the end answer? No Syrians nor anyone else have any answer for that… There is nothing to talk about! There is nothing to leverage or negotiate about. I am very pessimistic. There is no soon, any hope of a political settlement of the conflict.”

The other two panelists hewed more closely to the standard TJ script. Both argued that, while there is no “false equivalence” between the violations committed by the “Assad regime” and those committed by other parties, still, all violators should be held accountable.

Ghanem had earlier argued that accountability-seeking mechanisms could be used as “leverage” for the Syrian opposition in a future negotiated settlement. The relationship between pressure for “accountability” and momentum toward negotiations is a complex–and, as I demonstrated in this recent article, “Syria: Peacemaking or prosecutions?”, often an inverse–one. (When I wrote that piece, in early November, the prospects for reaching a negotiated political transition in Syria seemed greater than they do today.)

One misapprehension into which all three of the panelists at the Arab Center event seemed to have fallen was to conflate the idea of “accountability” almost completely with the path of criminal prosecutions. But as anyone who has studied the TJ field knows, there are numerous other mechanisms that have been used to enact accountability other than Western-style courts of law. South Africa’s TRC was one such mechanism. It was widely (and correctly) lauded for helping enable South Africans to make the transition from a deepseated system of colonial expropriation and Apartheid to a much more inclusive system that enabled the “White” colonists to remain in the country on a basis of political equality with its indigenes– and to achieve this without triggering a massive new race war between those two sides (though the transition was accompanied by very lethal fighting between the two major Black African political forces.)

The main premise of the TRC was that as part of the transition to political equality, it was necessary to draw a line under the violence of the past and to offer a full amnesty from prosecutions for all the perpetrators of that violence provided they (a) had stopped committing it; and (b) provided a full description of the violent acts they had committed, such as could help bring a degree of legal and emotional “closure” to survivors of the violence and others bereaved by it or otherwise affected by it.

The exact terms of the TRC’s “deal” with former perpetrators were painstakingly negotiated among the parties to the transition– principally, the Apartheid era’s ruling National Party and the anti-Apartheid African National Congress (ANC). The Apartheid government possessed overwhelming military, military, and socioeconomic force throughout the whole of South Africa; and it would never have agreed to end Apartheid and transition to a one-person-one-vote system in South Africa if its leaders had not been offered an amnesty. If there had been no TRC, the whole of Southern Africa might still be riven with terrible conflicts, to this day. The “offer” of amnesty was backed up the existence in the country of a fairly well-functioning judicial system. But the main factor motivating perpetrators to come forward and participate in the often riveting public hearings that the TRC held all around the country was the desire most of them felt to allow their families, their communities, and their country to move forward.

In my 2006 book, Amnesty After Atrocity? Healing Nations after Genocide and War Crimes, I looked at the effectiveness of South Africa’s TRC and compared it with the very different post-conflict mechanisms that, in that same period of 1992-94, had been adopted by Mozambique and post-genocide Rwanda. Those two other cases effectively “bracketed” what the South Africans agreed to do. In Rwanda, the post-genocide government was heavily inclined towards prosecutorialism, supporting both the creation and work of a UN-established International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the use of a very broad campaign of national-level prosecutions of suspected genocidaires. In Mozambique, by contrast, an extremely lengthy and ugly civil war was brought to an end in 1992 when the two main parties to it, the ruling Frelimo movement and the opposition Renamo, were brought together in a negotiation conducted by a Vatican-sponsored peace group and agreed to end their combat on the basis of a blanket amnesty for previous perpetrators of violence from both sides. The United Nations then stepped in with a broad program for demilitarization, demobilization, and reintegration into their home societies of the former fighters from both sides (DDR).

In my 2006 book, Amnesty After Atrocity? Healing Nations after Genocide and War Crimes, I looked at the effectiveness of South Africa’s TRC and compared it with the very different post-conflict mechanisms that, in that same period of 1992-94, had been adopted by Mozambique and post-genocide Rwanda. Those two other cases effectively “bracketed” what the South Africans agreed to do. In Rwanda, the post-genocide government was heavily inclined towards prosecutorialism, supporting both the creation and work of a UN-established International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and the use of a very broad campaign of national-level prosecutions of suspected genocidaires. In Mozambique, by contrast, an extremely lengthy and ugly civil war was brought to an end in 1992 when the two main parties to it, the ruling Frelimo movement and the opposition Renamo, were brought together in a negotiation conducted by a Vatican-sponsored peace group and agreed to end their combat on the basis of a blanket amnesty for previous perpetrators of violence from both sides. The United Nations then stepped in with a broad program for demilitarization, demobilization, and reintegration into their home societies of the former fighters from both sides (DDR).

Intense inter-group conflict of any kind of course inflicts massive damage on a country’s economy, including its most basic infrastructure, so societies emerging from such conflicts have numerous, extremely pressing human and economic needs. In this context, the relative costs– and therefore, also opportunity costs– of the TJ mechanisms used are definitely a factor. I used public documentation to calculate the costs of these mechanisms as follows (p.209):

- Each case completed at the ICTR : $42,300,000

- Each amnesty application at the TRC: $4,290

- Each case in Rwanda’s planned “local-style” gacaca courts (projected): $581

- Mozambique: each former fighter demobilized/reintegrated: $1,075

- South Africa: each former fighter demobilized/reintegrated: $1,066.

In that concluding chapter of the book, I presented (pp.212-13) a critique of the degree of “accountability” that advocates of prosecutorialism judge that their favored approach provides, noting that the kind of personal “accountability” required of perpetrators by a court of law is very thin indeed compared with, for example, that required in TRC or other similar mechanisms.

I also presented (p.241) a list of nine “meta-tasks” that, based on my previous analysis in the book– and on my own experience of having lived and worked in an area wracked by civil conflict, during the first six years of Lebanon’s civil war– I concluded that societies recovering from grave inter-group conflict need to undertake. It runs as follows:

Top rank (all of equal urgency):

-

- Establish rigorous mechanisms to guard against any relapse back into conflict and violence.

- Actively promote reconciliation across all inter-group divisions.

- Build an equality-based domestic democratic order that allows for nonviolent resolution of internal differences and respects and enforces human rights.

- Restore the moral systems appropriate to an era of peace.

- Reintegrate former combatants from all the previously fighting parties into the new society.

- Start restoring and upgrading the community’s physical and institutional infrastructure.

- Start righting the distributional injustices of the past.

Second rank (of somewhat less urgency):

-

- Promote psychological healing for all those affected by the violence and the atrocities, restoring dignity to them. (If the top-rank tasks are all addressed, those moves will anyway do much to achieve this; but it will probably need continuing attention.)

- Establish such records of the facts as are needed to meet victims’ needs (death certificates; identification of the burial sites; etc) and to start to build a record for history.

In the real world, decisions on what to do with individuals accused of having committed grave infractions nearly always get made in the context of a negotiation over the nature and terms of a major societal transition to a new political order. “String ’em all up on the lamp-posts!” or “Line ’em all up and shoot them!” are versions of one notable, non-negotiated type of such decision– and a type that notably doesn’t augur well for the political tone of the new order. In Syria, the way that ISIS or the bunch of Al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadis who currently control Idlib treat accused government supporters who fall under their sway definitely falls into this category.

Negotiating an end to a conflict– or acting with restraint in the event no negotiation proves possible– nearly always augurs a better outcome. At the end of WW-II, in the Asian theater, the Japanese Emperor was able to negotiate surrender terms on fairly favorable terms that ensured his dynasty’s continuation in office (and his own exculpation from responsibility for any of Japan’s preceding war crimes)–but in return for allowing the Americans and their allies to set up an international criminal tribunal to try certain Japanese decisionmakers, and numerous other concessions. In Germany, there was no negotiated end to the fighting; and the Russian, French, and British leaders (whose peoples had suffered most gravely from the Nazis’ actions) were all baying for extreme retribution. But the US public was relatively distant from the battlefield. That allowed Secretary of War Henry Stimson and President Harry Truman– both of whom were also aware of the disastrous sequelae of the punitive approach the victorious Allies had imposed on post-WW-I Germany– to argue for, and implement, the much more restrained approach to post-war justice that the Nuremberg trials represented.

Recent developments in Syria make the prospect of a negotiated end to the country’s lengthy civil war seem more remote today than they did a few months ago. The country’s 22 million people have been held in the vice of this conflict, and victim to the wiles of numerous outside actors and interveners much more than to those of any domestic actors, for nine long years. (This was also, interestingly, the case in Mozambique. Much of the terrible violence that Renamo used in its campaign to control as many Mozambicans as possible as a way of pressuring and overthrowing the Frelimo government had been organized and underwritten by South Africa’s Apartheid. The intra-Mozambican negotiations that brought an end to the war only made progress after a weakened South Africa started to withdraw that support.)

Throughout the first six years of Syria’s civil war, the determination of the United States and several allied governments (Turkey, Qatar, the Saudis, the UAE) to accept nothing less than the complete overthrow of the Assad government stymied all attempts by the United Nations and others to attain a negotiated end to the war. After Pres. Trump assumed office, he was less devoted to total “regime change” than Pres. Obama had been… and since late 2018 or so, the UAE has pulled back from its focus on regime change. Turkey also, from the Astana Agreement of September 2018 on, was clearly exploring some kind of “regional super-powers mega-deal” with Russia and Iran, that could help ramp down, or even bring to a negotiated end, Syria’s civil war.

More recently, though, Trump has pulled back from his fondness for a pullback from Syria. And perhaps he has started to see US military involvement in Syria as helping to serve his broader campaign of “maximum pressure” against Iran? Turkey has also pulled back from its commitment to Astana and is currently squaring up for a possibly broader military clash with Syrian government forces?

So the prospect for a negotiated settlement to the Syrian civil war has receded some. But it has certainly not disappeared completely. If nine years of slogging fighting– accompanied by terrible, unspeakable atrocities being suffered by people from all “sides”–has not succeeded in bringing about a “decisive” victory for any side, then surely an end to this war that is negotiated in some way is the only reasonable path, and the only path that can draw a line under the suffering of the past nine years? A viable negotiating forum has already been established by the United Nations. Let us hope it can complete its work as soon as possible, and that as part of this process the negotiators can find a list of mutually acceptable ways to deal with the whole range of transitional justice issues. And these, as noted above, go considerably further than the kinds of war-crimes trials so beloved by the Western media.