Over the New Year’s break, North Korea’s military test-fired some short-range (350-400 kilometer) ballistic missiles, while the country’s news agency reported that it was testing a new 600 mm multiple rocket launcher system capable of carrying nuclear weapons.

On Saturday, the often erratic-seeming North Korean leader Kim Jong-un expressed his commitment, “to respond with nuke for nuke and an all-out confrontation for an all-out confrontation.” He said he had ordered more powerful weapons to “absolutely overwhelm the U.S. imperialist aggressive forces and their puppet army.”

But actually, just how erratic is Kim? His recent actions and comments came in the context of South Korea having undertaken unprecedentedly broad joint exercises with the U.S. military, in and around its terrain. And yesterday, the press secretary of South Korean President Yoon Yoon Suk-yeol said that, “In order to respond to the North Korean nuclear weapons, the two countries [South Korea and the United States] are discussing ways to share information on the operation of U.S.-owned nuclear assets, and joint planning and execution of them accordingly.”

(Senior U.S. defense officials tried to walk back or downplay that announcement.)

Pres. Yoon is a new, and potentially destabilizing, factor in the long-tangled geopolitics of the Korean Peninsula. He is a political and social conservative who came to power last May at the end of the five-year term of Pres. Moon Jae-in. Moon was much more of a reformer, domestically and in intra-Korean affairs. When he was in office he pioneered steps to reach out to the North and work toward peaceful reunification, which were widely supported by the South Korean public. In 2018, he held two meetings with Kim Jong-un, one of them in the northern capital, Pyongyang. (Much of his outreach to Kim was paralleled by Pres. Donald Trump’s similar efforts, though there is little or no evidence that their moves were coordinated.)

By contrast, Pres. Yoon is much more hawkishly anti-North (as well as more socially conservative.) One of his first acts as president was to move his office to the Ministry of National Defense, and one of his foreign trips was to NATO’s Madrid Summit in June.

I started out responding to the latest news from Seoul by idly wondering whether Yoon’s relationship with Washington could be characterized as similar to Israel’s. But pretty soon I thought a more productive comparison would be between Kim’s relationship with China* and Israel’s with the United States.

There are many evident differences between these two cases, I know. But at the level of nuclear-weapons geopolitics, the parallels are striking.

In both cases, the smaller party in the relationship—which has received massive amounts of help from the larger party over the course of many decades—initially developed its independent nuclear arsenal with the stated goal of “deterring” or fending off its local adversaries… But then, the smaller state discovered that its command of a nuclear triggering capability gave it not just considerable freedom of action to buck the preferences of its larger-state backer but also considerable power to compel it to accede to the smaller state’s actions. That is, effectively, the power to blackmail the larger state into compliance. (For more info on the Israel case, see here.)

Or maybe the chronology I implied there is not accurate. Maybe the smaller state’s discovery of the triggering-cum-blackmailing aspect of having a wholly-owned nuclear arsenal did not occur subsequent to the development of the nukes but was part of the plan all along? Who knows?

But that is a minor issue. The big issue is that these two small states, North Korea and Israel, are able to defy the wishes of every other country in the world, including their superpower backers, because they are able to use nuclear blackmail.

This immediately raises two related questions:

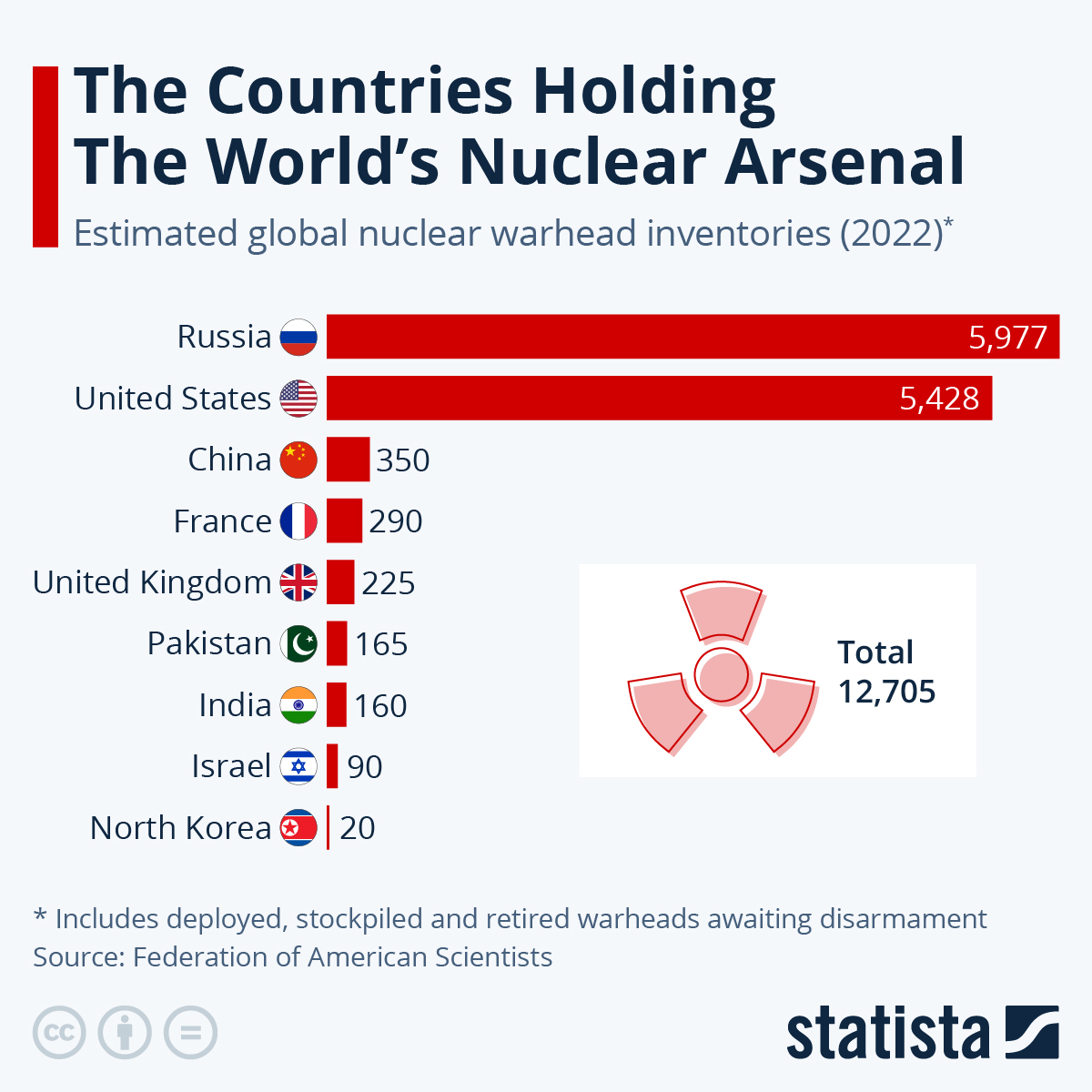

- If these states’ respective large-power backers did not also have (and face a threat from) very large, indeed, quite plausibly omnicidal, nuclear arsenals, then the “triggering” potential of the small states’ arsenals would be much less scary/threatening. The blackmailing effect of the small states’ arsenals is nearly wholly a function of the existence of the broader nuclear-terror regime at the global level.

- If one of the key effects of these smaller states’ possession of nuclear weapons has been to allow them to continue to defy world opinion and international law in a broad range of different ways, then what can we say about the effects of the possession of much larger and more deadly nuclear arsenals by the world’s much bigger powers?

All of which underlines the urgency of redoubling our efforts to dismantle all the world’s nuclear arsenals. The existence of these arsenals places all of humanity on a precarious hair-trigger for the quite possibly total extinction of our species. But it has also, in West Asia, in the Korean Peninsula, and elsewhere, kept frozen in place very damaging conflicts that continue until today to blight the lives of millions—though these conflicts should and could have been resolved through energetic and rights-respecting negotiations many decades ago.

- Footnote: I should note that for many years China was not the only substantial large-state backer of North Korea. Back in the day, the Soviet Union also was. Russia has a small direct border with North Korea and is anyway a significant factor in the complex nuclear-weapons balance in East Asia.