It’s just over a month since a family emergency called me away from the work I had been doing, posting a daily-per-year bulletin here to track the world-historical developments of each of the 500 years since 1520 CE. Such family-crisis interruptions can be very disorienting. But I’ve reached an age/stage in my life where I’ve weathered enough of them to understand that I have the resilience to be able to return to my work afterwards. Plus, when this latest crisis hit, I was already planning to take a pause in the project, just a few days later than when the crisis hit… And in the planning for the pause, I was already thinking I might explore approaches other than just continuing the year-per-day approach I had pursued since January 1.

That approach had several advantages. During a period in which I knew I’d be busy for more than half my work-time on projects for my publishing company, Just World Books, the year-per-day scheme was limited, clearly defined, and relatively time-economical to implement. It was also, from my perspective as a learner, extremely productive! I learned so much from pursuing it!

But it had many drawbacks. There are clear reasons why history has never actually been taught, learned, or even (except in some few circumstances) explored or presented in this way. Events of world-historical impact don’t unfold in tidy 12-month packages. They sort of rollick over the years/decades/centuries, kicking in on some occasions with explosive force then returning, often, to a quiet background somnolence. (There were the added complications for much of the period I was dealing with, 1520 -1695 CE, that at some point there, many European and other countries made the eleven-day shift from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar, whereas others, including England, still hadn’t made that shift as of 1695; and many countries still considered that the year– and therefore the enumerating of the years?– began in March. So which “year” did a particular event actually happen in, anyway? It often seemed hard to tell… )

I likened the process to trying to discern/describe the view from outside my window by looking through the heavy-ish Venetian blinds I have and just describing what I see by looking through one of the spaces defined by the slats, each time; then the next day shifting my gaze up to the next space. But of course, while engaged in the daily/yearly writing project, it was impossible not to “peep” to spaces higher or lower than than the one designated for that day.

Anyway, it has now been more than five weeks since I jumped off the daily/yearly hamster wheel and for now I am not planning to return to it. One of the factors that helps inform this choice is that I’m now confident that I can limit the burden of my work for Just World Books to a more manageable level. I currently have no plans for any new book releases any time in the foreseeable future, having released in the last half-year both one new title, Women Surviving Apartheid’s Prisons by Shanthini Naidoo, and one new edition of a now-classic JWB title: the 3rd edition of The Gaza Kitchen by Laila El-Haddad and Maggie Schmitt. My commitment to these and my 20-plus other authors is to keep their books in print, available, and appropriately marketed. And meantime, I can get back to digging deeper into my own intellectual production.

Also, over the past weeks, while I’ve been doing some pretty engrossing family things I have also had time to think about next steps for Project 500 Years. I have always wanted this project to focus on the whole concept of “the West” and its role in world affairs; and at a time when a defense of “Western values” is such a strong leitmotif of the foreign policy of the United States and other self-identified “Western” nations it seems particularly valuable to take a close look at exactly how it was that a small handful of countries perched on the Western (Atlantic) coast of Europe came to create globe-girdling empires in the first place, from the 15th century CE onwards, and then to maintain their “Western” domination of the world until today…

It was actually pretty late in this process that the leaders and ideologues of these empires came to tag their ideologies as “Western”. Maybe that was a function of the US-Soviet Cold War? Prior to that, tags like “Christian”, “civilized”, or “White” had been more common– along with, of course, more nation-specific tags like “English”, “British”, “French”, “Spanish”, etc… But the former group of tags were self-consciously communal, designed to highlight the common interests of the originally West-European group.

I can explore these ideological matters later on.

In the current/upcoming phase of the project, I want to take each of the historically significant West-European empires one at a time, chronologically by order of their founding, and delve into its ontogeny as well as the distinctive contribution each made to the development of “Western” world domination. So I’ll take them in this order:

- Portugal

- Spain

- England

- Netherlands

- France.

We can make a few initial observations about this group:

- They are all, as noted, perched on the Atlantic coast of the European landmass.

- By the end of the 16th century CE, they had all developed significant capabilities and experience in shipbuilding, maritime navigation, and naval warfighting– as well as in land-based warfighting.

- For Portugal and Spain, all those capabilities were developed during the lengthy campaigns they fought to expel the Muslims from Iberia.

- For all five countries, these capabilities were developed by fighting each other, and sometimes other Europe-based powers. These lengthy contests were pursued by land and sea, both within Europe and along its often rugged West-facing coasts. Later, they were also pursued in colonial/imperial spaces very far from Europe.

- Of the five, only Spain and France had any significant land-mass at home over which they ruled, which forced them to devote attention and resources to ensuring a favorable balance of power in Europe.

- The other three all had a land footprint in Europe that was extremely slight, and on the margins. That forced on them a heavy reliance on global trading networks to create and maintain their wealth and power– or even, indeed, to assure their very existence as “nation-states” distinct from and not subject to the control of much larger neighbors. (Spain took over Portugal through the years 1580-1640, but the Portuguese then regained their independence…. When the Protestant Netherlands declared its independence from Spain in 1588, its leaders briefly considered asking England to take them over. Both episodes were pretty intriguing and revelatory about the process of “nation-state” formation.)

- In general, in this “post-Latin” era in Europe, the process of nation-state formation for these five states was closely tied to, or dependent on, their building of large, globe-girdling empires. Regulation and management of the empires relied on the development of adequate administrative and financial-management capabilities in their capitals.

- Aggressive pursuit of perceived “Christian” interests around the world was a huge motivating factor for the Portuguese and the Spanish as they built their empires, though pursuit of profit was also always a factor, too. For the Portuguese, who early on encountered and felt the need to aggressively counter the large, robust trading networks that various Muslim were operating in the Indian Ocean, their pursuit of “Christianizing” goals was also married to strong Islam-crushing goals.

- For the English and French, Christian evangelization was a factor in their empire-building, but not with anything like the priority it had for the Iberians. For the Dutch it was barely a factor at all: their empire was nearly wholly about pursuing profit.

- During the period when these five powers were establishing their world empires, there were also still some significantly-sized land-based empires in the Eurasian landmass: those based in China, India, Persia, and Anatolia. But the maritime empires built by the Europeans were a new and aggressive breed, with features that from the early 18th century on enabled them to erode and then destroy the power of the land-based empires…

We’ll come to that period, later. For now, let us just recall that prior to 1433, China’s Ming empire maintained an extremely large naval capability. Between 1405 and 1433 it sent seven massive naval expeditions around the coast of the Indian Ocean, “from Borneo to Zanzibar.” At the center of each fleet were multi-decked, nine-masted treasure ships called “star rafts”, each 440 feet long. Each fleet carried enough food for a year; they navigated straight across the Indian Ocean from Malaysia to Sri Lanka, with the aid of compasses and closely calibrated astronomical/navigational charts…

The English historian Roger Crowley has written of these expeditions (Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire, pp. xx, xxiv) that,

Although they had ample capacity to quell pirates and depose monarchs and also carried goods to trade, they were primarily neither military nor economic ventures but carefully choreographed displays of soft power. The voyages of the star rafts were nonviolent techniques for projecting the magnificence of China to the coastal states of India and East Africa…

[After 1433] the star rafts never sailed again. The political current in China had changed: the emperors strengthened the Great Wall and shut themselves in. Oceangoing voyages were banned, all the records destroyed. In 1500 it became a capital offense to build a ship with more than two masts…

China’s Ming-dynasty emperors and officials had clearly decided that the terrestrial imperatives of their large land-based empire needed to take precedence over the wanderings of their fleets of star rafts. Crowley wrote that that left a power vacuum in the Indian Ocean– which the navigator Vasco da Gama, on an expedition sent out by the Portuguese king, started to fill from the moment he reached India in 1498.

Crowley is an excellent writer of history who mines an extensive array of sources to craft the kinds of narrative that address many of the same questions that I like to ask. I am 60% of the way through Conquerors, and maybe one of my first tasks as I address the “Portugal” phase of P500Yrs should be to write a good assessment of it here… Stay tuned.

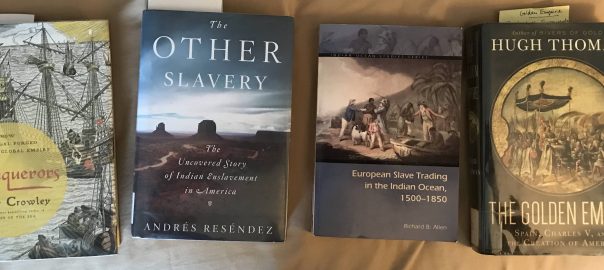

(The image above is of some of my current and planned reading… Thank God for great public libraries!)