So here we are, at 200 years after the fateful “contact” year of 1492 CE and all around the world there are developments that help illustrate the changes the coming of Western imperialism has made to the lives of hundreds of millions of people. So much to write about today!

I’ll keep the biggest story till last. Here’s the news budget for 1692:

- In Scotland, King William’s enforcers undertake a massacre against the pro-James Macdonalds, at Glencoe.

- In the Puritan-English colony of Massachusetts, religious hysteria leads to witch-trials at Salem.

- In Beijing, the Kangxi Emperor issues an Edict of Tolerance toward Christians.

- In North America, the Spanish Empire takes back the Pueblos lost to Indigenous resistance 12 years earlier.

- The capital of New Spain, Mexico City, sees a massive food riot.

- In English-controlled Jamaica, an earthquake and tsunami swallow the major city.

- English-controlled Barbados sees a large-scale rebellion of enslaved workers.

In Scotland, King William’s enforcers undertake a massacre against the pro-James Macdonalds, at Glencoe.

I’ve written before about the intense contestation in Ireland between supporters of King William III (basically, the Protestant settlers) and those of deposed King James II (mainly Catholic Indigenes.) That contest had been definitively won by the “Orangeist” supporters of William, and a final peace had been concluded at Limerick in October 1691.

In Scotland, too, there was some resistance to William, and support for James. Support for James was not wholly based on Catholicism, but also included some Scottish-nationalist sentiment since his family, the Stuarts, was a Scottish family.

Be that as it may, English-Wikipedia tells us that in 1692 this happened:

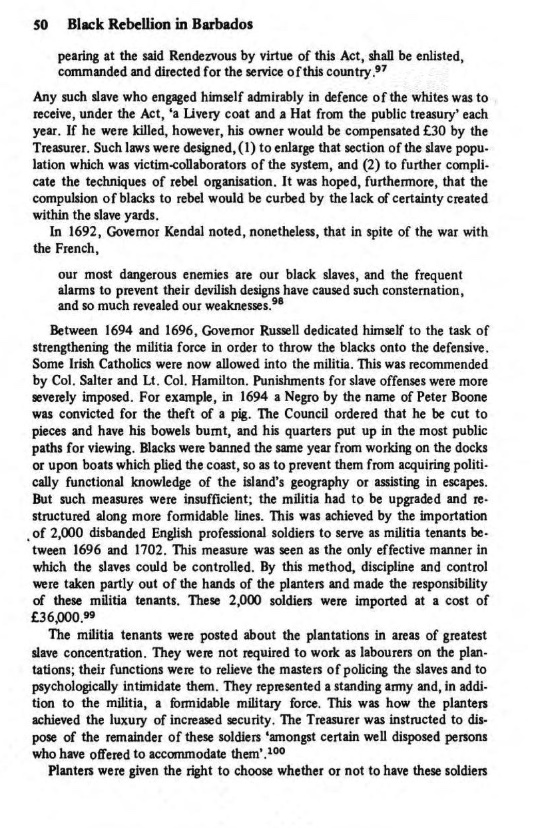

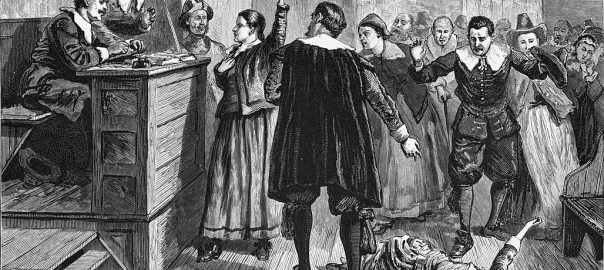

The Massacre of Glencoe (Scottish Gaelic: Murt Ghlinne Comhann) took place in Glen Coe in the Highlands of Scotland on 13 February 1692. An estimated 30 members and associates of Clan MacDonald of Glencoe were killed by Scottish government forces, allegedly for failing to pledge allegiance to the new monarchs, William II and III and Mary II.

Although the Jacobite rising of 1689 was no longer a serious threat by May 1690, unrest continued in the remote Highlands which consumed resources needed for the Nine Years War in Flanders. In late 1690, the Scottish government agreed to pay the Jacobite [= pro-James] clans a total of £12,000 for swearing loyalty. However, arguments between the chiefs over how to divide the money meant by December 1691 they still had not done so.

Under pressure from William, Secretary of State Lord Stair decided to make an example as a warning of the consequences for further delay. The Glencoe MacDonalds were not the only ones who failed to meet the deadline, while the Keppoch MacDonalds did not swear until early February. The reason for their selection is still debated but appears to have been a combination of internal clan politics, and a reputation for lawlessness that made them an easy target.

While there are examples of similar events in Scottish history, the massacre was unusual in the context of late 17th century society and its brutality shocked contemporaries. It became a significant element in the persistence of Jacobitism in the Highlands during the first half of the 18th century, and remains a powerful symbol for a variety of reasons.

(A quick personal disclaimer here. My father’s family was descended somehow from the Macdonalds and claimed the later Jacobite organizer Flora Macdonald as an ancestor.)

In the Puritan-English colony of Massachusetts, religious hysteria leads to witch-trials at Salem.

With-hunting and witch-trials were a big thing throughout much of Protestant Northern Europe in those decades, just as hunting for “fake” converts from Judaism or Islam were a big deal in the ultra-Catholic monarchies of Spain and Portugal. Clearly, religious hysteria was rife in the Christian world in that period… So it was probably not surprising that it arrived in North America, in the ultra-Puritan English colony of Massachusetts, as well.

English-WP tells us this about the witch-trials that opened at Salem that year:

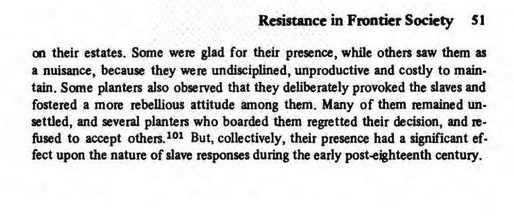

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than two hundred people were accused. Thirty were found guilty, nineteen of whom were executed by hanging (fourteen women and five men). One other man, Giles Corey, was pressed to death* for refusing to plead, and at least five people died in jail.

Arrests were made in numerous towns beyond Salem and Salem Village… The grand juries and trials for this capital crime were conducted by a Court of Oyer and Terminer** in 1692 and by a Superior Court of Judicature in 1693, both held in Salem Town, where the hangings also took place. It was the deadliest witch hunt in the history of colonial North America. Only fourteen other women and two men had been executed in Massachusetts and Connecticut during the 17th century.

The episode is one of Colonial America’s most notorious cases of mass hysteria. It has been used in political rhetoric and popular literature as a vivid cautionary tale about the dangers of isolationism, religious extremism, false accusations, and lapses in due process. It was not unique, but a Colonial American example of the much broader phenomenon of witch trials in the early modern period, which took place also in Europe. Many historians consider the lasting effects of the trials to have been highly influential in subsequent United States history. According to historian George Lincoln Burr, “the Salem witchcraft was the rock on which the theocracy shattered.”

*Pressing to death was a particularly painful and long-drawn-out means of killing.

** This is a fancy French name for a type of English law court.

The banner image above is a detail from a well-known engraving of one of the witch-trials.

In Beijing, the Kangxi Emperor issues an Edict of Tolerance toward Christians.

(This item is located here by chance, but it makes an interesting contrast with the previous one!)

In Beijing, the Kangxi Emperor had been on the throne since he was six years old, in 1661, and for the early years of his reign effective power was wielded by the Four Regents of the Kangxi Emperor, under the watchful eye of his grandmother, Grand Empress Dowager Zhaosheng. She had died in 1688.

English-WP tells us this about the emperor’s actions toward the Jesuits and other Christians who buzzed around his court– both in 1692 and in the following years:

In the early decades of the Kangxi Emperor’s reign, Jesuits played a large role in the imperial court. With their knowledge of astronomy, they ran the imperial observatory. Jean-François Gerbillon and Thomas Pereira served as translators for the negotiations of the Treaty of Nerchinsk [with Russia]. The Kangxi Emperor was grateful to the Jesuits for their contributions, the many languages they could interpret, and the innovations they offered his military in gun manufacturing and artillery, the latter of which enabled the Qing Empire to conquer the Kingdom of Tungning.

The Kangxi Emperor was also fond of the Jesuits’ respectful and unobtrusive manner; they spoke the Chinese language well, and wore the silk robes of the elite. In 1692, when Pereira requested tolerance for Christianity, the Kangxi Emperor was willing to oblige, and issued the Edict of Toleration, which recognized Catholicism, barred attacks on their churches, and legalized their missions and the practice of Christianity by the Chinese people.

However, controversy arose over whether Chinese Christians could still take part in traditional Confucian ceremonies and ancestor worship, with the Jesuits arguing for tolerance and the Dominicans taking a hard-line against foreign “idolatry”. The Dominican position won the support of Pope Clement XI, who in 1705 sent Charles-Thomas Maillard de Tournon as his representative to the Kangxi Emperor, to communicate the ban on Chinese rites. Through de Tournon, the Pope insisted on sending his own representative to Beijing to oversee Jesuit missionaries in China. Kangxi refused, wanting to keep missionary activities in China under his final oversight, managed by one of the Jesuits who had been living in Beijing for years.

On 19 March 1715, Pope Clement XI issued the papal bull Ex illa die, which officially condemned Chinese rites. In response, the Kangxi Emperor officially forbade Christian missions in China, as they were “causing trouble”.

As a footnote, I have to say I I am intrigued by this portrait of the Kangxi Emperor, painted by an un-named court artist in 1699. Such a contrast to all those highly stylized portraits of great big, silk-swathed lumps of emperors (including one of him) that had long been the norm!

Of course, we don’t know if he actually would spend much time sitting simply in his well-organized library engaging in book-learning. But it’s interesting that he wanted certain people to think he did so…

In North America, the Spanish Empire takes back the Pueblos lost to Indigenous resistance 12 years earlier.

As we know, back in 1680, the Tewa religious leader Popé or Po’pay had organized and led a very successful uprising against the Spanish-Catholic settlers in today’s New Mexico, ejecting them from twelve settlements in the region. Then, in 1688, a guy called Diego de Vargas was appointed Governor of New Mexico, though he did not arrive to assume his duties until February 1691. His task was to reconquer and pacify the New Mexico territory for Spain.

On this page, WP tells us this how he did this:

In July 1692, de Vargas and a small contingent of soldiers returned to Santa Fe. They surrounded the city and called on the Pueblo people to surrender, promising clemency if they would swear allegiance to the King of Spain and return to the Christian faith. After meeting with de Vargas, the Pueblo leaders agreed to surrender, and on 12 September 1692 de Vargas proclaimed a formal act of repossession. De Vargas’ repossession of New Mexico is often called a bloodless reconquest, since the territory was initially retaken without any use of force.

De Vargas had prayed to the Virgin Mary, under her title La Conquistadora [!]… for the peaceful re-entry. Believing that she heard his prayer, he celebrated a feast in her honor. Today, this feast continues to be celebrated annually in Santa Fe as the Fiestas de Santa Fe. Part of those annual fiestas is a novena of masses in thanksgiving. Those masses are also done with processions from the Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi to the Rosario Chapel… In the second decade of the 21st century, members of Native American tribes and pueblos protested the pageant, recalling the subsequent retaking of Santa Fe.

The focus of these protests was The Entrada—a reenactment of de Vargas’s re-entry into Santa Fe that has long been seen as inaccurate by historians and culturally offensive by Native Americans. The most recent round of protests against The Entrada started in 2015. That year, silent protestors raised placards citing historical facts at odds with the narrative present when the re-enactors reached Santa Fe’s historic Plaza to portray the retaking of the city. Protests in 2017 resulted in 8 arrests; though the charges were later dismissed. Following the protests and months of negotiation the Entrada was removed from The Santa Fe Fiesta celebration.

On June 18, 2020 the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico removed a Statue of Diego de Vargas that had been erected 150 years earlier. The statue was one of several removed as wider efforts to remove controversial statues across the United States.

The capital of New Spain, Mexico City, sees a massive food riot.

At this portion of English-WP, I learned this about this riot:

Considering the small proportion of the Spanish population in Mexico as opposed to the Indian and mixed-race casta populations and that the fact that there had been few challenges to Spanish rule since the early sixteenth-century conquest, likely meant the huge riot on June 8, 1692 was a shock to Spaniards. A mob of Indians and castas partially destroyed the viceregal palace and the building of the city council (cabildo or ayuntamiento). Painter Cristóbal de Villalpando’s 1696 painting of the Zócalo still shows the damage to the viceregal palace from the mob’s attempt to burn it down.

This is part of a longer WP page that’s a biography of a guy called Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, born in 1645, and described as “A polymath and writer [who] held many colonial government and academic positions.” In 1692, I believe he was the Official Geographer of New Spain, which as in the context of any settler-colonial state was a key role.

Anyway the WP section on the 1692 food riot continues thus:

Sigüenza wrote a lengthy “racy, vivid account of the riot…he also offered a fascinating profile of his own reactions to the dramatic events.” It is a major source for the Spanish version of events, published as “Letter of Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora to Admiral Pez Recounting the incidents of the Corn Riot in Mexico City, June 8, 1692.” In 1692, there was a severe drought in New Spain and a disease attacking wheat, called in Nahuatl “chiahuiztli”. The crown sought sources of corn outside the general sourcing area for the capital, but the price of corn rose significantly. This caused a severe shortage of food for the poor. Tensions rose significantly in the capital, and came to a flashpoint when neither the viceroy nor the archbishop, to whom the crowd of petitioners appealed as legitimate authorities, would meet directly with them. Following the failed attempt to get any official audience or promise of aid, the crowd began throwing stones and set fire to the major buildings around the capital’s principal square. Sigüenza saved most of the documents and some paintings in the archives, at the risk of his own life. This act preserved a considerable number of colonial Mexican documents that would otherwise have been lost. Scholars have noted the importance of the 1692 riot in Mexican history.

I found that many of the pieces of information on Sigüenza’s page provided interesting glimpses of the life in the nearly 180-year-old settler-city of Mexico City and its culture. The link there to the “Casta” system was one such window.

Also, Sigüenza himself was a second-generation settler: His parents had both been born in “Old” Spain and met in “New” Spain, where he was born. He was “the second oldest and first male of nine siblings… He studied mathematics and astronomy under the direction of his father, who had been a tutor for the royal family in Spain.”

As a young man he entered the Jesuit order but was kicked out of it “for repeatedly flouting Jesuit discipline and going out secretly at night.” He then, “studied at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico… and excelled at mathematics and developed a lifelong interest in the sciences.” Etc., etc.

In English-controlled Jamaica, an earthquake and tsunami swallow the major city.

In English-ruled Jamaica, an earthquake struck the island’s major city on June 7, 1692. English-WP gives these details:

Known as the “storehouse and treasury of the West Indies” and as “one of the wickedest places on Earth”, Port Royal was, at the time, the unofficial capital of Jamaica and one of the busiest and wealthiest ports in the Americas, as well as a common home port for many of the privateers and pirates operating on the Caribbean Sea.

The 1692 earthquake caused most of the city to sink below sea level. About 2,000 people died as a result of the earthquake and the following tsunami, and another 3,000 people died in the following days due to injuries and disease.

This WP account gives no breakdown on how many of the casualties of the quake were members of Jamaica’s very numerous enslaved workforce.

Here’s what it does say:

Two-thirds of the town, amounting to 33 acres (13 ha), sank into the sea immediately after the main shock. According to Robert Renny in his An History of Jamaica (1807): “All the wharves sunk at once, and in the space of two minutes, nine-tenths of the city were covered with water, which was raised to such a height, that it entered the uppermost rooms of the few houses which were left standing. The tops of the highest houses were visible in the water and surrounded by the masts of vessels, which had been sunk along with them.”

Before the earthquake the town consisted of 6,500 inhabitants living in about 2,000 buildings, many constructed of brick and with more than one storey, and all built on loose sand. During the shaking, the sand liquefied and the buildings, along with their occupants, appeared to flow into the sea. More than twenty ships moored in the harbour were capsized. One ship, the frigate Swann, was carried over the rooftops by the tsunami. During the main shock, the sand was said to have formed waves. Fissures repeatedly opened and closed, crushing many people. After the shaking stopped the sand again solidified, trapping many victims.

At Liguanea (present-day Kingston), all the houses were destroyed and water was ejected from 40-foot-deep (12 m) wells. Almost all the houses at St. Jago (Spanish Town) were also destroyed.

Numerous landslides occurred across the island…

A pocket watch, made in the Netherlands by the French maker Blondel in about 1686, was recovered during underwater archaeological investigations led by Edwin Link in 1959. The watch was stopped with its hands pointing to 11:43 AM; this matches well with contemporary accounts of the timing of the earthquake.

Even before the destruction was complete, some of the survivors began looting, breaking into homes and warehouses. The dead were also robbed and stripped, and, in some cases, had fingers cut off to remove the rings that they wore.

In the immediate aftermath of the earthquake, it was common to ascribe the destruction to divine retribution on the people of Port Royal for their sinful ways…

After the earthquake, the town was partially rebuilt. But the colonial government was relocated to Spanish Town, which had been the capital under Spanish rule.

English-controlled Barbados sees a large-scale rebellion of enslaved workers.

… Which brings us handily to Barbados, where the most important development of the year took place.

I am happy to be able to use here the words of the pre-eminent Barbadian historian Prof. Hilary Beckles himself, from his 1984 study Black Rebellion In Barbados: The Struggle Against Slavery, 1627-1838, which is freely available in fulltext from that link.

We join his narrative when he has been describing how fearful the planters on Barbados had become in the early 1690s, of the possibility of an uprising of the enslaved, originally-African workers on their (always hyper-profitable) sugar-cane plantations. Two factors had made the planters more fearful: the number of “White” indentured servants on the island, who had long formed the backbone of the militia used to suppress the enslaved, had dwindled; and the continuing war against the French– which was apparently being fought against French positions elsewhere in the Antilles, as well as in Europe– had greatly weakened the military strength on Barbados…

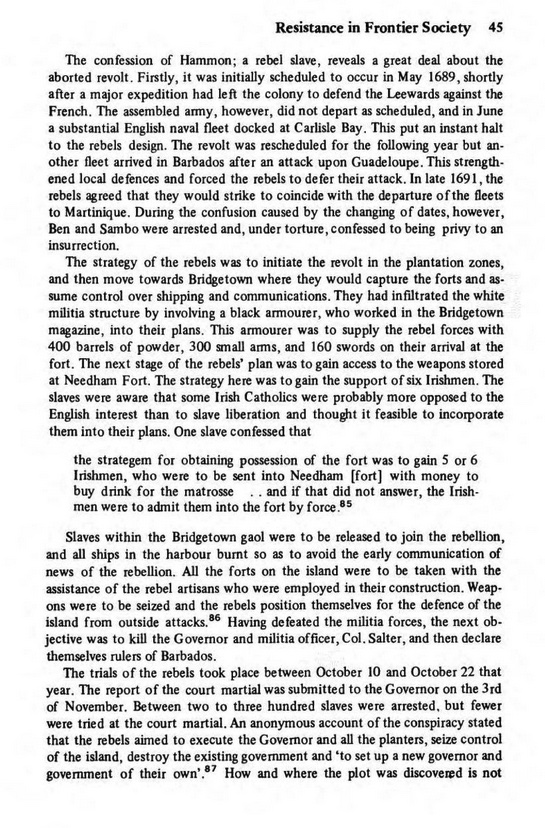

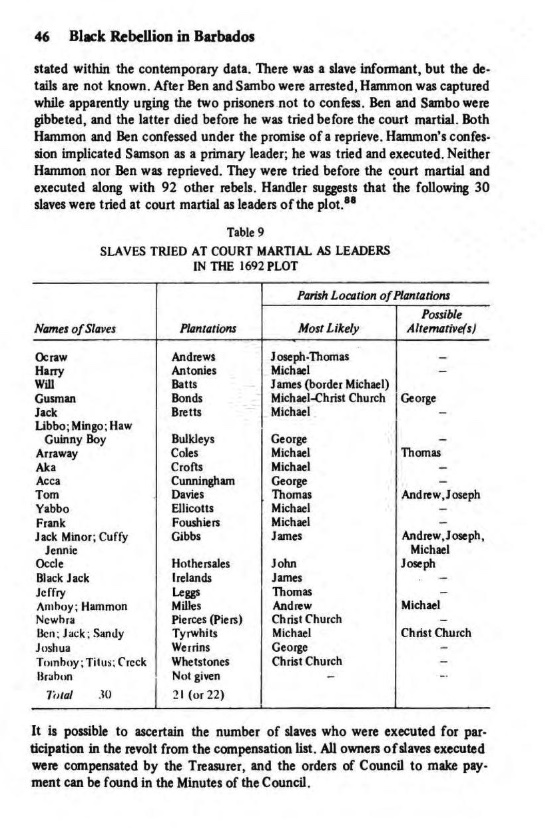

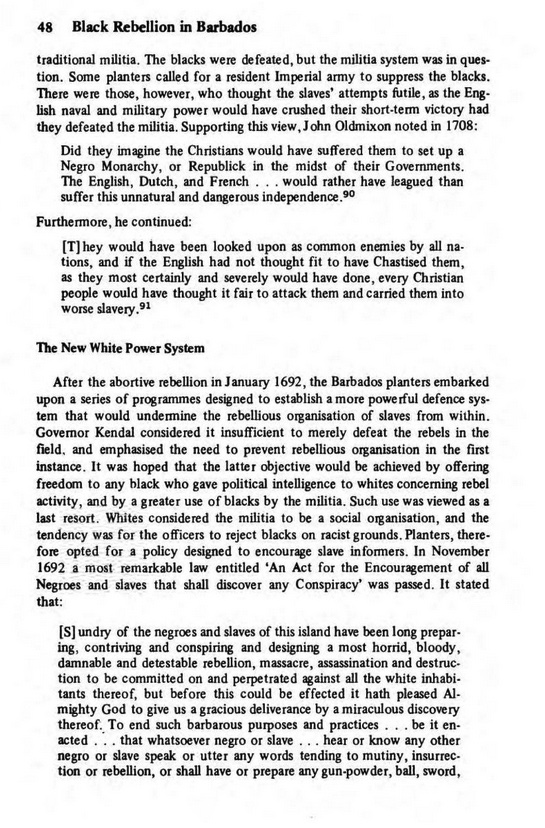

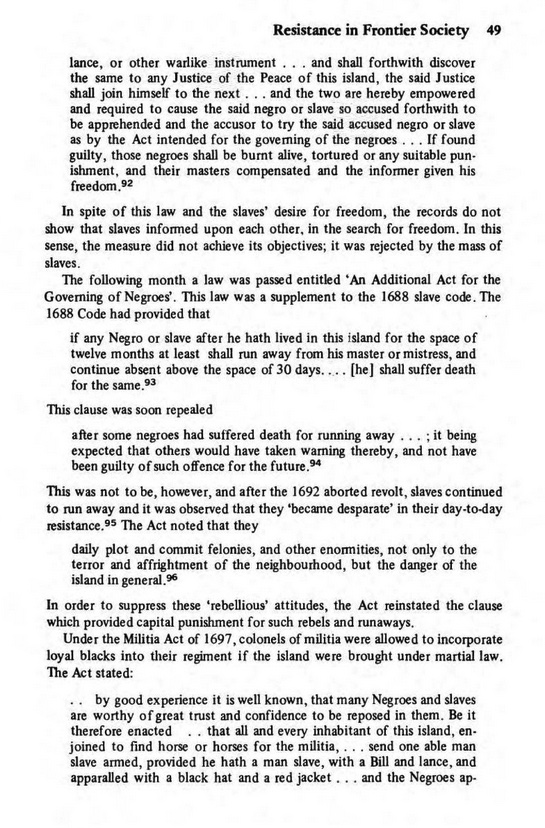

So here we were, on Barbados. The 7.5 pages from Beckles I use here take us through the uncovering of this plot, the horrific aftermath, and the legal measures enacted immediately afterward to clamp down even harder on the enslaved. (On this first page, you can skip down to “The rebels were aware”, if you want):