1688 CE was a huge year in the history of “the big 4 (or 4.5)” of the Western imperialisms– being in order of empire-building Portugal, Spain, England, the Dutch UPs, with France being the 0.5 at the end.

These things happened:

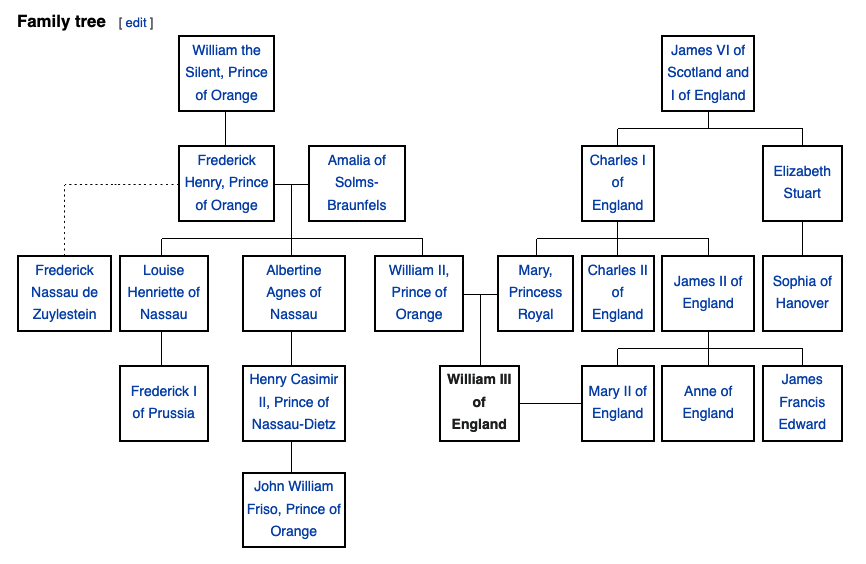

- The Stadtholder of Holland, William III of Orange, invaded England (ostensibly at the invitation of seven key members of the Anglican elite) and effectively ousted the very Catholic King James II who was both his father-in-law and his uncle, though the story put about was that James had “abandoned” his Crown. (He went to France.) Given that England and the UP’s had fought a number of naval wars over preceding decades, one big cause of which had been contestation for international trading routes and colonial power, what effect would the unification of these two noble houses on that competition?

- James had been the president of England’s “Royal Africa Corporation” and had wide control of English colonial ventures in the Caribbean and North America. What effect would his ousting have on all those ventures? (Answer: Not very much!)

- France also took the opportunity of William’s preoccupation with England to invade the Netherlands– but he invaded the Habsburg/Catholic portion of the Netherlands more than the UPs/Protestant portion, sparking a sprawling inter-imperial war that pitted France against virtually all the other imperial powers called the Nine Years’ War.

- France also took the opportunity to bombard Algiers, as the continuation of a multi-year attempt to cow its ruler into submission…

- But in Mergui/Myeik in today’s Myanmar, an anti-French uprising by officials of the Ayutthaya Kingdom captured a fortress the French had established there three years earlier and the colorful commander of the fortress, Chevalier de Beauregard, seemed to have ended up enslaved.

- Meanwhile, since in the pan-British context any tension between Protestants and Catholics was bound to have repercussions in Ireland, the ousting of James from England led to a mini-uprising by Protestant-settler “Apprentice Boys” in Derry, Ireland. The Boys shut all the gates of Derry, refusing to allow the (locally Catholic-dominated) army to enter. The Catholic army besieged Derry for 105 days until finally the Boys and their (William-ite) supporters were able to break the siege.

- Finally, in William Penn’s hoped-for “Holy Experiment” in Pennsylvania, the founder of a small colonial settlement of German-origined new converts to Quakerism and three of his companeros addressed a powerful remonstrance to the local Quaker Meeting on the issue of slavery.

I only have time to write very little here today. So I’ll start with the Germantown Friends’ remonstrance and then move to the business of the ouster of James.

The Remonstrance of the Germantown Friends

This is often considered the first emergence of clearly anti-slavery organizing by colonists in North America. (Of course, for a century or more already, Indigenes of the continent had very fiercely organized to resist the campaigns of the colonists to either enslave them in place or– as often happened– to capture them and transport them to the Caribbean to work as chattel labor there. Those Indigenes should rightly be considered the original “American” anti-slavery activists.)

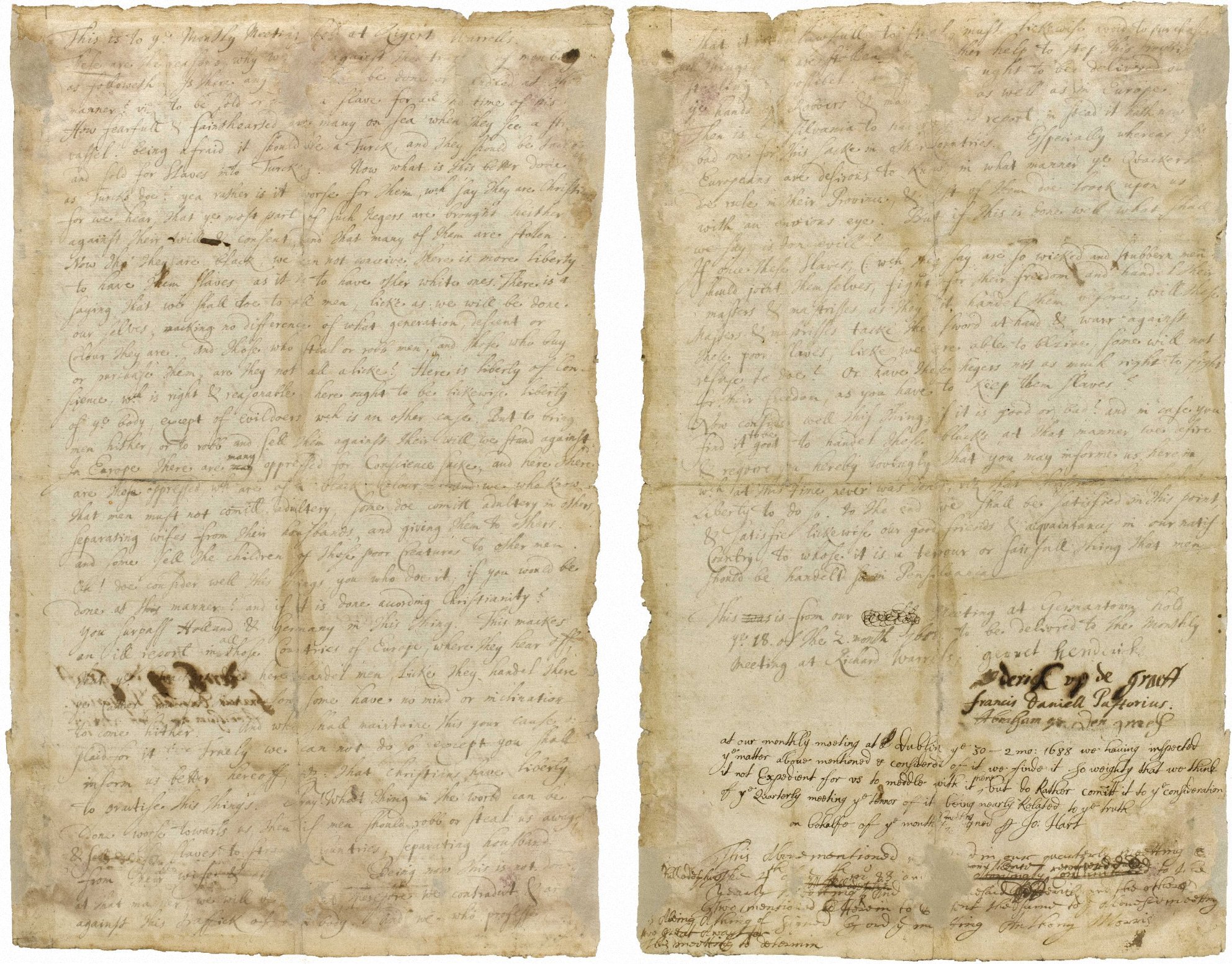

The original document of the 1688 remonstrance was found in 2005. You can see a facsimile of its two pages and a transcription of each, here. The Wikipedia page on the whole affair has some useful background.

My understanding of the matter is that, ever since the founder of Quakerism, George Fox, had gone to Barbados and to some English colonies on the N. American mainland in 1671, many or most Quakers had understood the guidance he gave on the issue of slavery as allowing them to engage in the institution, but in a “merciful” manner. And throughout the young, avowedly Quaker-led colony of Pennsylvania, many or most Quaker colonists exploited the labor of enslaved persons. Actually, the WP page on the Germantown remonstrance states (without, sadly, any attribution), that, “William Penn oversaw the economic progress of his colony and once proudly declared that during the course of a year Philadelphia had received ten slave ships.”

Francis Daniel Pastorius was the German/Dutch man who founded the settler-town known as “Germantown.” He and most of the other settlers there had not originally been Quakers, but most likely Mennonites: but they became Quakers at some point in their establishing of their settlement. Mennonites and Moravians and many other Anabaptists never participated in the institutions of slavery nearly as much as Quakers did; and they had suffered a lot for their beliefs back in Europe. So their remonstrance basically took the form of asking “Why should we inflict on enslaved Africans the same kinds of suffering that we have only just escaped from?”

Here are the opening sentences of their statement:

These are the reasons why we are against the traffik of men-body, as followeth: Is there any that would be done or handled at this manner? viz., to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? How fearful & fainthearted are many on sea when they see a strange vassel. being afraid it should be a Turck, and they should be tacken, and sold for slaves into Turckey. Now what is this better done, as Turcks doe? yea, rather is it worse for them wch say they are Christians, for we hear that ye most part of such negers are brought heither against their will & consent and that many of them are stollen. Now tho they are black, we can not conceive there is more liberty to have them slaves, as it is to have other white ones. There is a saying that we shall doe to all men licke as we will be done ourselves; macking no difference of what generation, descent or Colour they are. and those who steal or robb men, and those who buy or purchase them, are they not all alicke? Here is liberty of conscience wch. is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of ye body, except of evildoers, wch is an other case. But to bring men hither, or to robb and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe there are many oppressed for Conscience sacke; and here there are those oppressed wch are of a Black Colour…

Their whole text is very powerful. They addressed it to the local “Monthly Meeting” (full congregation) of the Quakers, of which they were a part.

WP gives us a version of what happened next:

The Meeting decided that although the issue was fundamental and just, it was too difficult and consequential for them to judge, and would need to be considered further. In the usual manner the Meeting sent the petition on to the Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting, where it was again considered and sent on to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (held in Burlington, NJ). Realizing that the abolition of slavery would have a wide and overreaching impact on the entire colony, none of the Meetings wanted to pass judgment on such a “weighty matter.” PYM minuted that they would send the petition to London Yearly Meeting, without mentioning whether they actually did so, and on this point no direct evidence has been discovered. The minutes of London Yearly Meeting do not mention the petition directly, apparently skirting the issue.

The practice of slavery continued and was tolerated in Quaker society in the years immediately following the 1688 petition.

That latter sentence is a great under-statement! Many Quaker individuals and communities in North America, in the Caribbean, and in the great English sea-ports of Bristol and Liverpool not only “tolerated” the institution of slavery but they very actively engaged in and profited from it, and not just in “the years immediately following the 1688 petition” but for many decades thereafter. (When I have time, I need to go back into that WP page and do some editing on it… )

Also, that is such a very Quaker story– namely, to see how the “bureaucracy” simply stalled and blocked those voices of conscience from being heard and acted upon.

Anyway, here’s a shout-out to these four men of conscience, who signed it:

England’s William-ite ‘Glorious Revolution’

So as we saw last year, since he had become King in 1685, James II had moved ever further toward dis-establishing the Anglican Church in England (and the rest of Britain), and toward favoring the many Catholics in his entourage. The proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back for those opposed to him came on June 10, 1688, when news broke that his Catholic second wife Mary of Modena had given birth to a son. Until that point, the king had had only two children, the daughters of his first wife, Mary and Anne, who had been raised (or had sort of become) Protestant; and they had been the heirs to the throne. But now, it looked as if the new infant, also James, would outrank them.

There had already been a group of seven Anglican nobles (including the Bishop of London) that had been in touch with William of Orange, who was married to James’s daughter Mary; and William had been making his own plans for an intervention. Now, that group sent a letter to William, which he received on June 30 (English/Julian-style dating.)

The “William III” page on WP tells us this happened:

William at first opposed the prospect of invasion, but most historians now agree that he began to assemble an expeditionary force in April 1688, as it became increasingly clear that France would remain occupied by campaigns in Germany and Italy, and thus unable to mount an attack while William’s troops would be occupied in Britain. Believing that the English people would not react well to a foreign invader, he demanded in a letter to Rear-Admiral Arthur Herbert that the most eminent English Protestants first invite him to invade. In June, Mary of Modena, after a string of miscarriages, gave birth to a son, James Francis Edward Stuart, who displaced William’s Protestant wife to become first in the line of succession and raised the prospect of an ongoing Catholic monarchy. Public anger also increased because of the trial of seven bishops who had publicly opposed James’s Declaration of Indulgence granting religious liberty to his subjects, a policy which appeared to threaten the establishment of the Anglican Church.

On 30 June 1688—the same day the bishops were acquitted—a group of political figures, known afterward as the “Immortal Seven”, sent William a formal invitation. William’s intentions to invade were public knowledge by September 1688. With a Dutch army, William landed at Brixham in southwest England on 5 November 1688. He came ashore from the ship Brill, proclaiming “the liberties of England and the Protestant religion I will maintain”. William’s fleet was vastly larger than the Spanish Armada 100 years earlier: approximately 250 carrier ships and 60 fishing boats carried 35,000 men, including 11,000 foot soldiers and 4,000 cavalry. James’s support began to dissolve almost immediately upon William’s arrival; Protestant officers defected from the English army (the most notable of whom was Lord Churchill of Eyemouth, James’s most able commander), and influential noblemen across the country declared their support for the invader.

James at first attempted to resist William, but saw that his efforts would prove futile. He sent representatives to negotiate with William, but secretly attempted to flee on 11/21 December, throwing the Great Seal into the Thames on his way. He was discovered and brought back to London by a group of fishermen. He was allowed to leave for France in a second escape attempt on 23 December. William permitted James to leave the country, not wanting to make him a martyr for the Roman Catholic cause; it was in his interests for James to be perceived as having left the country of his own accord, rather than having been forced or frightened into fleeing. William is the last person to successfully invade England by force of arms.

I’ll take this through the constitutional issues that ensued to the point where he and Mary are jointly crowned in April 1689:

William summoned a Convention Parliament in England, which met on 22 January 1689, to discuss the appropriate course of action following James’s flight. William felt insecure about his position; though his wife preceded him in the line of succession to the throne, he wished to reign as king in his own right, rather than as a mere consort… When the majority of Tory Lords proposed to acclaim her as sole ruler, William threatened to leave the country immediately. Furthermore, Mary, remaining loyal to her husband, refused.

The House of Commons, with a Whig majority, quickly resolved that the throne was vacant, and that it was safer if the ruler were Protestant. There were more Tories in the House of Lords, which would not initially agree, but after William refused to be a regent or to agree to remain king only in his wife’s lifetime, there were negotiations between the two houses and the Lords agreed by a narrow majority that the throne was vacant. On 13 February 1689, Parliament passed the Bill of Rights 1689, in which it deemed that James, by attempting to flee, had abdicated the government of the realm, thereby leaving the throne vacant.

The Crown was… [offered] to William and Mary as joint sovereigns. It was, however, provided that “the sole and full exercise of the regal power be only in and executed by the said Prince of Orange in the names of the said Prince and Princess during their joint lives”.

William and Mary were crowned together at Westminster Abbey on 11 April 1689 by the Bishop of London, Henry Compton. Normally, the coronation is performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury, but the Archbishop at the time, William Sancroft, refused to recognise James’s removal…

Two last things to add: (1) William and Mary never had children and there was quite some evidence that William may have been gay, fwiw. (2) The banner image above is a detail from a 1703 engraving of William and Mary.