In 1663 CE, just three years after Charles II was “restored” to the English throne, he, his advisors, and his parliament took several significant steps to consolidate the growth and reach of the country’s trans-oceanic empire. Specifically:

- Parliament passed a new Navigation Act that yet further tightened the restrictions on free trade that Cromwell’s Navigation Act had first imposed in 1651;

- the King granted a new monopoly over “trade” with Africa– that was, increasingly, the “trade” in enslaved persons– to a newly reconfigured Royal African Company; and

- he also issued a charter to eight of his key “noble” buddies, that granted them ownership and control over a landmass in North America called “Carolina.”

The year also saw a large-scale plundering raid on a Spanish fort on the mainland of today’s Mexico undertaken by an interesting, Jamaica-based character called Christopher Myngs who slipped with ease, back and forth, between the role of international pirate and that of high-ranking English naval officer. (Queen Elizabeth’s legacy of pirating lived on!)

So today, I’ll look at as many of those developments as I can.

The 1663 Navigation Act

The previous Navigation Acts passed by the English parliament had restricted merchants in England and its network of overseas colonies to shipping their merchandise only in English ships. English-WP tells us that this new, tighter Nav Act:

required all European goods, bound for America and other colonies… to be trans-shipped through England first. In England, the goods would be unloaded, inspected, approved, duties paid, and finally, reloaded for the destination. This trade had to be carried in English vessels (“bottoms”) or those of its colonies. Furthermore, imports of the ‘enumerated’ commodities (such as tobacco and cotton) had to be landed and taxes paid before continuing to other countries… This mandated change increased shipping times and costs, which in turn, increased the prices paid by the colonists. Due to these increases, some exemptions were allowed; these included salt intended for the New England and Newfoundland fisheries, wine from Madeira and the Azores, and provisions, servants and horses from Scotland and Ireland.

The most important new legislation embedded in this Act, as seen from the perspective of the interests behind the East India Company, was the repeal of legislation which prohibited export of coin and bullion from England overseas… This change had major implications for the East India Company, for England and for India. The majority of silver in England was exported to India, creating enormous profits for the individual participants, but depriving the Crown of England of necessary silver and taxation. Much of the silver exported was procured by English piracy directed against Spanish and Portuguese merchant ships bringing silver from their colonies in the Americas to Europe. It was later revealed that the Act passed Parliament due to enormous bribes paid by the East Indian Company to various influential members of Parliament.

Why am I not surprised?

‘Royal African Company’ gets new charter, new investors

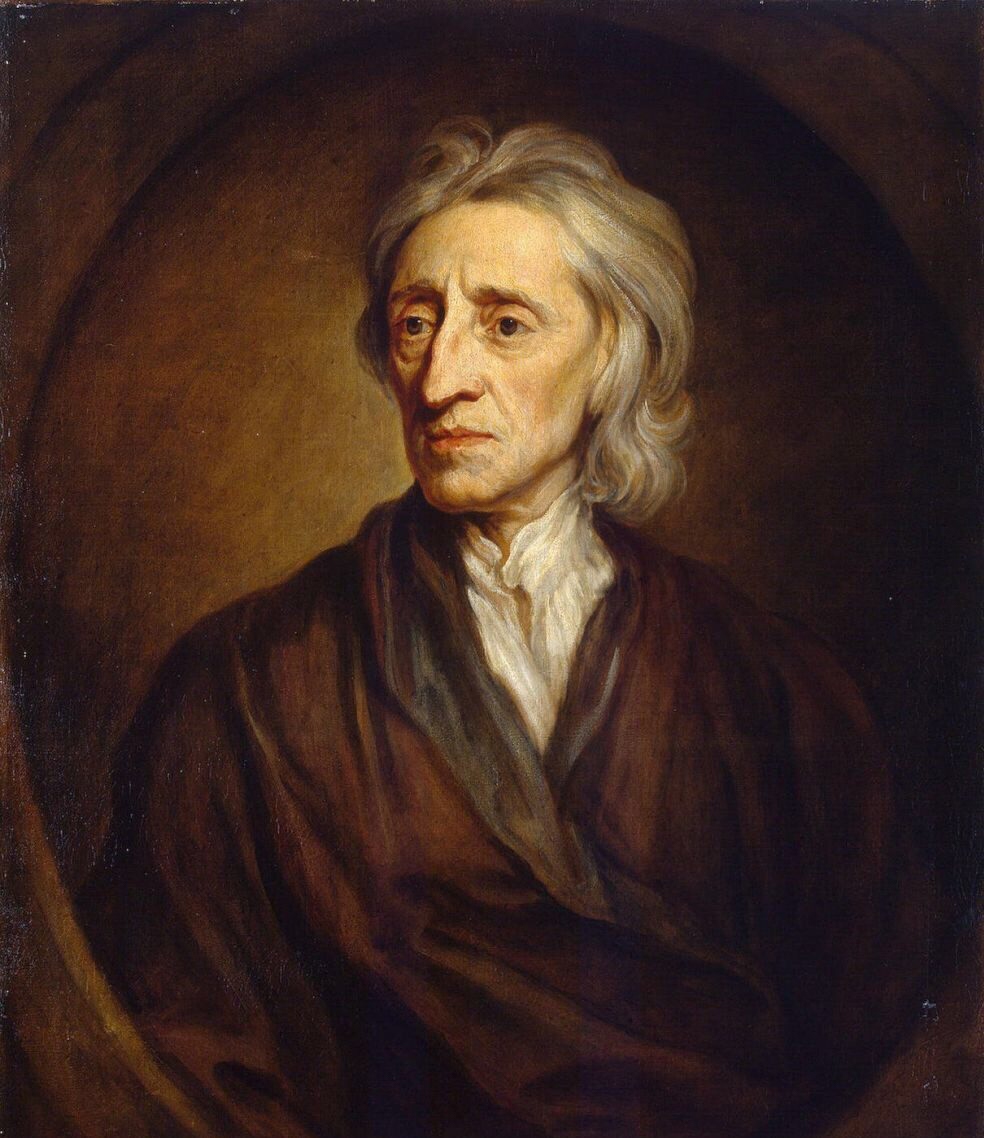

On September 27, 1663, the King issued a new, 1,000-year monopoly to the “Royal African Company of England” (RAC). The intention of it was apparently to incorporate new investors– among them, the new Queen Catherine (of Braganza), the Queen Mother, the diarist Samuel Pepys… and the “philosopher of toleration” John Locke.

English-WP tells us this:

In 1663 a new charter was obtained which also mentioned the trade in slaves… [I]t made a fresh start in the slave trade and there was only one factory of importance for it to take over from the East India Company, which had leased it as a calling-place on the sea-route round the Cape. This was Cormantin, a few miles east of the Dutch station of Caso Corso or Cape Coast Castle. The 1663 charter prohibits others to trade in “redwood, elephants’ teeth, negroes, slaves, hides, wax, guinea grains, or other commodities of those countries”. In 1663, as a prelude to the Dutch war, Captain Holmes’s expedition captured or destroyed all the Dutch settlements on the coast, and in 1664 Fort James was founded on an island about twenty miles up the Gambia river, as a new centre for English trade and power…

Forts served as staging and trading stations, and the Company was responsible for seizing any English ships that attempted to operate in violation of its monopoly (known as interlopers). In the “prize court”, the King received half of the proceeds and the Company half from the seizure of these interlopers.

A full or near-full text of the charter can be found in this page of British History Online, at Jan. 10th.

Hugh Thomas tells us (Slave Trade, p.199) that “Forty English ships set off for Guinea in the first year” of the new company’s operations. I’ll wait till next year to tell us what else they did.

King Charles also issues charter for “Carolina” in N. America

What a busy imperializing year 1663 was for England’s King Charles II. In March, he issued a separate charter—

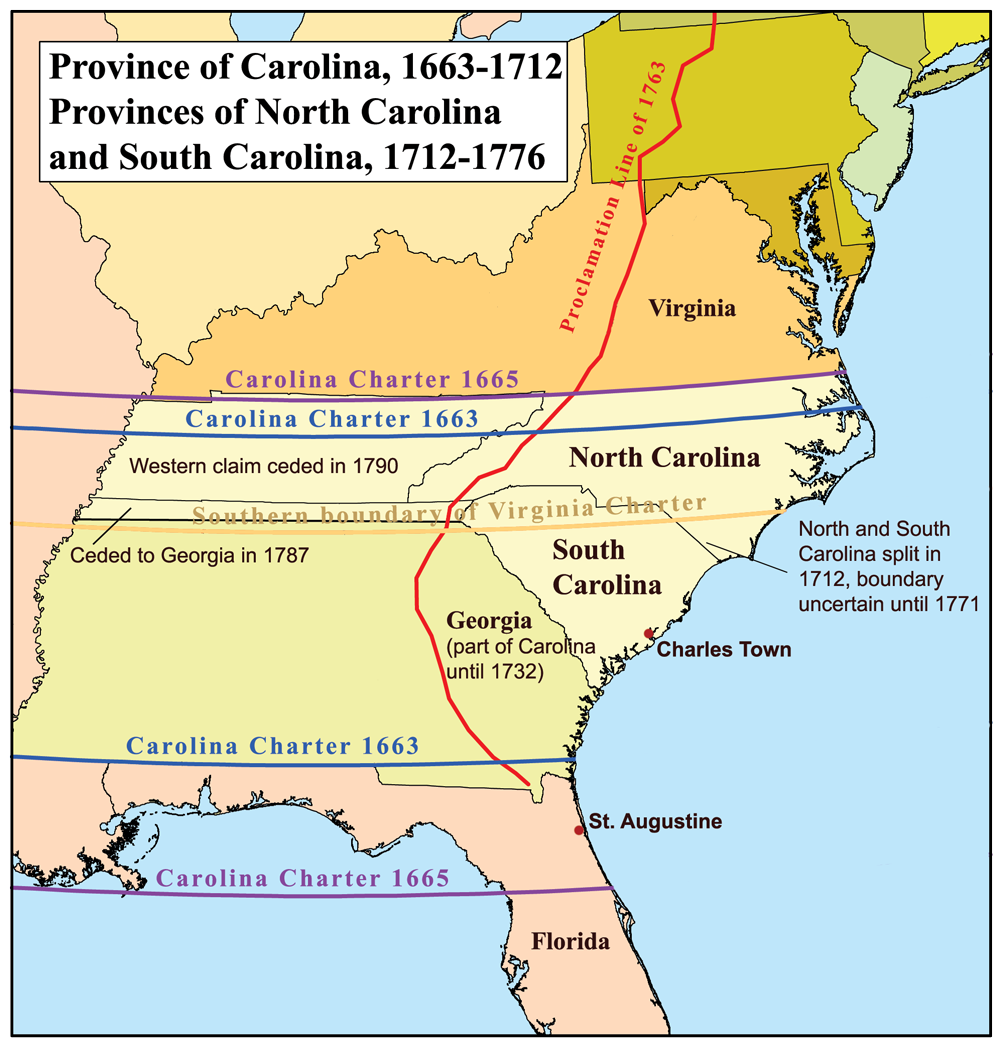

to a group of eight English noblemen, granting them the land of Carolina, as a reward for their faithful support of his efforts to regain the throne of England. The eight were called Lords Proprietors or simply Proprietors. The 1663 charter granted the Lords Proprietor title to all of the land from the southern border of the Virginia Colony at 36 degrees north to 31 degrees north (along the coast of present-day Georgia). The King intended for the newly created province to serve as an English bulwark to contest lands claimed by Spanish Florida and prevent their northward expansion.

The “Lords Proprietors” to whom this charter was given included many of the same people leading the RAC. One of them was Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, who in 1666 hired John Locke as his private secretary. The page on Wikipedia on the “Grand Model for the Province of Carolina” (the colony’s original Constitution) tells us that shortly after Locke signed on as Ashley Cooper’s private secretary,

he became secretary to the Lords Proprietors and began drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina and associated planning materials. The precise extent to which Locke shaped the substance of the Fundamental Constitutions is unknown, but he was undoubtedly guided at least on a general level by Ashley Cooper.

Locke’s position with the Lords Proprietors might be described as that of “chief planner” for Carolina. He drafted development standards for towns as well as an illustrative plan that he included in his instructions to the colonists…

Locke also wrote guiding principles for regional development that were remarkably similar to principles of modern planning, including aspects of sustainable development and smart growth…

Locke famously denounced slavery in the first sentence of his Two Treatises of Government, then proceeded to develop the new idea of natural equality. Since the Grand Model anticipated slavery, Locke has been labeled a hypocrite by some scholars for designing Carolina and then continuing to be associated with the venture after writing the famous indictment of slavery. While… Locke and Ashley Cooper anticipated that Carolina would have slaves, as did most other colonies, it is unlikely that they anticipated that it would become fundamentally dependent on slavery (i.e., a “slave society”) as later happened.

On the other hand, it must be admitted that Locke did have a certain financial interest in the institution of slavery. He invested in the notorious Royal African Company (chartered in 1660 under King Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland), which is said to have shipped tens of thousands of slaves from West Africa to the British colonies in North America.

That latter statement is such a dishonest fudge! Also, the first sentence of Two Treatises of Government (shown at right) is by no means a blanket denunciation of slavery…

Back to the “Grand Model” for Carolina:

The Grand Model allocated more land (60 percent) and representation to “the people” than to the nobility, suggesting that yeoman farmers were envisioned ultimately to become the backbone of the colony. Nevertheless, a slave-owning elite was also part of the formula from the beginning. Where Ashley Cooper saw slavery as playing a vital role was in the establishment of the principal estates. In December, 1671, he advised against bringing too many of “the poorer sort” to the colony until “men of estates” could first “stock the country with Negroes, cattle, and other necessarys.”

The transformation of Carolina from a colony with slaves to a slave colony, and later a slave society, began when slaveowners from Barbados became the dominant force in Carolina politics during the 1780s…

John Locke, it should also be recalled, had come from a family from south-west England that had long been involved in various imperial projects including slave-trading.

Prominent English privateer raids Spanish North America

In 1655, you will recall, Oliver Cromwell sent a naval force to the Caribbean to capture as many as possible of the Spanish-controlled islands under his “Western Design”, but it succeeded only in capturing Jamaica. That island thenceforth became a nest for English-led pirates, who used it as a base from which to raid Spanish ships in the Caribbean basin, many of which were carrying very valuable cargoes.

In 1663, a prominent English seafarer called Christopher Myngs decided to go after a bigger, much richer target. This was the Spanish fort at Campeche, on the western shore of the Yucatan. English-WP tells us what happened:

Pirate captains from across the Caribbean volunteered their services, and Myngs amassed the largest pirate fleet ever seen with 14 ships and 1400 pirates. The primarily English fleet was subsequently joined by four French ships and three Dutch privateer ships for a total of more than 20 vessels. Leading the fleet was Myngs’ flagship HMS Centurion and the smaller vice-flagship the Griffin. The fleet included already-well-known pirates… It is likely it included other younger sailors who would later captain pirate vessels of their own and replicate Myngs’ tactics. They left Port Royal in January, joined by other smaller vessels as they went but losing contact with the Griffin.

Early the following month, the fleet arrived in Campeche Bay. By night, Myngs landed approximately 1000 men a short distance from the city on 8 February. The following morning, Spanish lookouts saw the fleet’s smaller ships at first light and sought to raise the alarm, though unaware that Myngs’ much larger 40-gun flagship lay just out of sight. Regardless, the warning came too late and the pirates attacked at approximately 8:00 am. The pirates initially struggled against the city’s 150-strong militia who used high ground of flat-roofed stone houses to their advantage. Fighting was fierce and Myngs was injured… After a 2-hour-long battle, 50 Spanish defenders and 30 English, Dutch and French pirates were dead. The sole surviving Spanish official agreed to terms of surrender and the pirates sacked the city, taking an additional 14 vessels from the harbour when they left 2 weeks later. The pirates plundered a total of 150,000 Spanish pieces of eight.

The defeat of Campeche’s defences was so comprehensive and the subsequent outrage so strong that King Charles was forced to forbid further similar raids. That policy was enforced across the Caribbean for the remainder of the term of [Jamaica’s] Governor Thomas Modyford. When he died in 1679, similar raids were organised including the attack on Veracruz in 1683 and the raid on Cartagena later that same year. Both plans involved landing a large ground-based force to attack a fortified settlement which otherwise might have been able to defend itself against a seaborne raid.

Myngs returned to England the following year to recover from his injuries.

Reading more about Myngs was interesting. He initially went to Jamaica in 1655 as a naval officer with high recommendations from his commanding officers. But Campeche was not his only successful (and essentially piratical) raid against Spanish positions on the mainland. His page on WP tells us:

In February 1658, he returned to Jamaica as naval commander, acting as a commerce raider [whatever that was] during the Anglo-Spanish War. During this period Myngs acquired a reputation for unnecessary cruelty, sacking several Spanish colonial towns while in command of whole fleets of buccaneers. In 1658, after beating off a Spanish naval attack, he raided Spanish colonies around the coast of South-America; failing to capture a treasure fleet, he destroyed the colonial settlements in Tolú and Santa Maria in New Grenada instead; in 1659 he plundered Cumaná, Puerto Cabello and Coro where a large haul of silver in twenty chests was seized.

The Spanish government, upon hearing of Myngs’ actions, protested to no avail to the English government of Oliver Cromwell about his conduct. Because he had shared half of the bounty of his 1659 raid, about a quarter of a million pounds, with the buccaneers against the explicit orders of Edward D’Oyley, the English Commander of Jamaica, he was arrested for embezzlement and sent back to England in the Marston Moor in 1660.

The Restoration government retained him in his command however, and in August 1662 he was sent to Jamaica commanding the Centurion in order to resume his activities as commander of the Jamaica Station, despite the fact the war with Spain had ended. This was part of a covert English policy to undermine the Spanish dominion of the area…

So this was the same old policy of the English government as what we had seen a century earlier, under Elizabeth, namely the use by the government of piratical mercenaries to harass and plunder opponents. Continuous with what had happened under Elizabeth, under (the anti-monarchist) Cromwell, and now under Charles II. And though the king might have been (a tiny bit) embarrassed by what Myngs did at Campeche, two years later he was “made Vice-Admiral in Prince Rupert’s squadron” and served as “Vice-Admiral of the White” under the Lord High Admiral, who happened to be King Charles’s brother James, Duke of York, the President of the Royal Africa Company.

What a toxic mix of royalty, government/naval officials, and private business interests we had there in London in those days.

The banner image above is a corner of the old Spanish fort at Campeche.