In 1655 CE, the four European imperial powers were continuing their work as usual all around the world: plundering, enslaving, fighting (including amongst themselves), conducting political intrigue at home, etc. Oh just the smell of the super-profits available to the investors in colonial plunder was enough to drive a person wild! (A notably strange and tragic period in human history.)

Anyway, let’s at it. Here are today’s six stories:

- Spain establishes a new settler-city in Mindanao, Philippines

- Spanish Viceroy of Peru faces new Mapuche uprising

- The Netherlands’ Grand Pensionary (Grand Vizier) John de Witt makes an auspicious marriage

- His man in New Amsterdam, the anti-Semite Peter Stuyvesant, annexes “New Sweden”

- English naval-warfare genius Blake subdues Dey of Tunis

- Cromwell’s expedition captures Jamaica.

Spain establishes a new settler-city in Mindanao, Philippines

This is the city now called Surigao, at the northern end of Mindanao. WP tells us that before the Spanish conquest, “Fishing villages dotted along the coast facing the Hinatuan Passage while Mamanwa tribes inhabited the interior highlands. The confluence of three major bodies of water- Pacific Ocean, Surigao Strait and Mindanao Sea, kept the area inhabited continuously for many centuries.” Where the Spanish established their city was previously a site called Bilang-Bilang that, “served as a port of call for inter-island vessels. It was renamed Banahao which became an integral part of the old district of Caraga, a[settler-] town founded on June 29, 1655.”

At some point later, “Caraga” was renamed Surigao. WP also tells us that in addition to its strategic location, the area of Surigao, “has abundant mineral reserves including gold, iron, manganese, silica, cobalt, copper, chromite and among the world’s largest nickel deposits in Nonoc Island.” Nice for looting by the Spanish colonizers!

Spanish Viceroy of Peru faces new Mapuche uprising

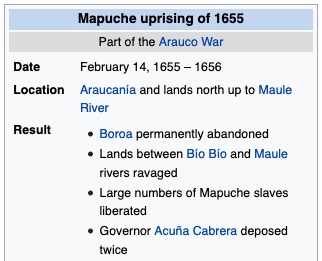

I am not going to apologize for my fascination with the Mapuche. Here they go again! Look at the results of this uprising, at right.

English-WP has a whole page on the Mapuche Uprising of 1655. It cites as one of the causes of the 1655 uprising the fact that the Spanish administrators and mine-owners in this part of southern Chile had not stuck by their previous agreement to stop enslaving the indigenous Mapuche in their ghastly, rapacious, and too-often lethal mines:

Albeit there was a general ban of slavery of indigenous people by Spanish Crown the 1598–1604 Mapuche uprising that ended with the Destruction of the Seven Cities made the Spanish in 1608 declare slavery legal for those Mapuches caught in war. Mapuches “rebels” were considered Christian apostates [whaaat?] and could, therefore, be enslaved according to the church teachings of the day. In reality, these legal changes only formalized Mapuche slavery that was already occurring at the time, with captured Mapuches being treated as property in the way that they were bought and sold among the Spanish. Legalisation made Spanish slave raiding increasingly common in the Arauco War.

The “Arauco War” was the broader Spanish-Mapuche conflict in the area known as the Araucania Region. Anyway, the war lasted into 1656 and resulted in some significant gains for the Mapuche side.

The Netherlands’ Grand Pensionary (Grand Vizier) John de Witt makes an auspicious marriage

I know pitiably little about the political system in Netherlands at the time that it had been experiencing its “Golden Age” of imperial conquests of stunning reach and success in all the oceans of the world. So finding out that Grand Pensionary (= Grand Vizier, more or less) Johan de Witt got married this year enabled me to learn a little more.

From the WP page on de Witt, I learned this:

Johan de Witt was a member of the old Dutch patrician family De Witt. His father was Jacob de Witt, an influential regent and burgher from the patrician class in the city of Dordrecht, which in the seventeenth century, was one of the most important cities of the dominating province of Holland. Johan and his older brother, Cornelis de Witt, grew up in an elite social environment in terms of education, his father having as good acquaintances important scholars and scientists… Johan and Cornelis attended the Latin school in Dordrecht, which imbued both brothers with the values of the Roman Republic.

He became a lawyer in The Hague. Then, this:

De Witt became the pensionary of Dordrecht. In 1652, in the city of Flushing, De Witt found himself faced with a mob of angry demonstrators of sailors and fishermen. An ugly situation was developing. However, Johan’s cool-headedness at the age of 27 calmed the situation. Elders saw greatness in him.

On 16 February 1655, De Witt married Wendela Bicker, the daughter of Jan Bicker, an influential patrician from Amsterdam, and Agneta de Graeff van Polsbroek. This marriage made De Witt member of the leading Amsterdam regent-oligarchy Bicker-De Graeff… De Witt became a relative to the strong republican-minded brothers Cornelis and Andries de Graeff, and to Andries Bicker. Because of this relationship, he was able to rely on the political and economic help of Amsterdam during his tenure as head of government…

In 1653, the States of Holland elected De Witt councilor pensionary… Since Holland was the Republic’s most powerful province, he was effectively the political leader of the United Provinces as a whole—especially during periods when no stadholder had been elected by the States of most Provinces.

And yes, that was the case at that time.

WP continues:

The raadpensionaris of Holland was often referred to as the Grand Pensionary by foreigners as he represented the preponderant province in the Union of the Dutch Republic. He was a servant who led the States of province by his experience, tenure, familiarity with the issues, and use of the staff at his disposal. He was in no manner equivalent to a modern Prime Minister.

That last sentence caused me some thought. I think it’s true that a modern “Prime Minister” nearly always serves as a minister to a head of state; but in Holland/Netherlands there was no head of state at that time. That’s why I think likening the GP position to that of a Grand Vizier in, say, the Ottoman Empire may be more appropriate: an official who comes up through the ranks of a strong “civil service” and is supported by it.

Anyway, more from WP:

Representing the province of Holland, De Witt tended to identify with the economic interests of the shipping and trading interests in the United Provinces. These interests were largely concentrated in the province of Holland, and to a lesser degree in the province of Zeeland. In the religious conflict between the Calvinists and the more moderate members of the Dutch Reformed Church that arose in 1618, Holland tended to belong to the Dutch Reformed faction in the United Provinces. Not surprisingly, De Witt also held views of toleration of religious beliefs.

De Witt was a pretty staunch anti-monarchist. This is interesting, a little lower down:

Together with his uncle, Cornelis de Graeff, De Witt brought about peace with England after the First Anglo-Dutch War with the Treaty of Westminster in May 1654. The peace treaty had a secret annex, the Act of Seclusion, forbidding the Dutch ever to appoint William II’s posthumous son, the infant William [of Orange], as stadholder. This annex had been attached on instigation of Cromwell, who felt that since William III was a grandson of the executed Charles I, it was not in the interests of his own republican regime to see William ever gain political power.

On 25 September 1660, the States of Holland under the prime movers of De Witt, De Graeff, his younger brother Andries de Graeff and Gillis Valckenier resolved to take charge of William’s education to ensure he would acquire the skills to serve in a future—though undetermined—state function. Influenced by the values of the Roman republic, De Witt did his utmost anyway to prevent any member of the House of Orange from gaining power, convincing many provinces to abolish the stadtholderate entirely. He bolstered his policy by publicly endorsing the theory of republicanism. He is supposed to have contributed personally to the “Interest of Holland“, a radical republican textbook published in 1662, by his supporter Pieter de la Court.

In the period following the Treaty of Westminster, the Republic grew in wealth and influence under De Witt’s leadership. De Witt created a strong navy, appointing one of his political allies, Lieutenant Admiral Jacob van Wassenaer Obdam, as supreme commander of the confederate fleet.

Spoiler alert: de Witt does not come to good end….

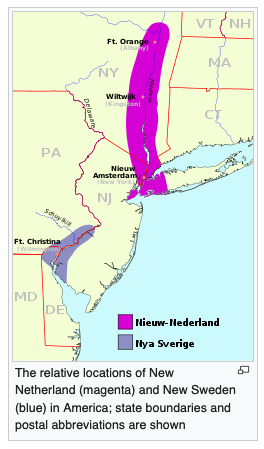

His man in New Amsterdam, the anti-Semite Peter Stuyvesant, annexes “New Sweden”

In summer 1655, the man who had been Governor of New Netherland since 1647, Peter Stuyvesant, “sailed down the Delaware River with a fleet of seven vessels and about 700 men and took possession of the colony of New Sweden, which was renamed ‘New Amstel’.”

Stuyvesant was not a nice man, to say the least. He was a member of the Dutch Reformed Church but not as tolerant of followers of other faiths as many DRC people. The WP page on him says he, “particularly supported Antisemitism, and loathed Jews not merely through religion, but also through race.”

He persecuted Jews, Lutherans, and Quakers, though the Dutch West India Corporation that he worked for and represented urged him to be more tolerant.

Specifically, he:

refused to allow the permanent settlement of Jewish refugees from Dutch Brazil in New Amsterdam (without passports), and join the handful of existing Jewish traders (with passports from Amsterdam). Stuyvesant attempted to have Jews “in a friendly way to depart” the colony. As he wrote to the Amsterdam Chamber of the Dutch West India Company in 1654, he hoped that “the deceitful race, — such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ, — be not allowed to further infect and trouble this new colony.” He referred to Jews as a “repugnant race” and “usurers”, and was concerned that “Jewish settlers should not be granted the same liberties enjoyed by Jews in Holland, lest members of other persecuted minority groups, such as Roman Catholics, be attracted to the colony.”

And regarding the Quakers:

In 1657, the Quakers, who were newly arrived in the colony, drew his attention. He ordered the public torture of Robert Hodgson, a 23-year-old Quaker convert who had become an influential preacher. Stuyvesant then made an ordinance, punishable by fine and imprisonment, against anyone found guilty of harboring Quakers. That action led to a protest from the citizens of Flushing, which came to be known as the Flushing Remonstrance, considered by some historians a precursor to the United States Constitution’s provision on freedom of religion in the Bill of Rights.

The banner image above is a 1664 painting of New Amsterdam.

English naval-warfare genius Blake subdues Dey of Tunis

Even though all the “big” action in global history had long ago shifted to the world’s oceans and their shores and inlets, there were still some very minor actions in that relatively small and nearly wholly enclosed body of water, the Mediterranean. Specifically the conflict between (some combination of) Christian powers and the Ottoman Empire ground on there, as did the intermittent naval contests between different Christian powers, primarily Spain and France.

In 1655, England’s Admiral Robert Blake– oops, not an admiral, per order of the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell– decided to enter the Med. Possibly a perplexing decision, given that the main task Cromwell had given the English Navy in December 1654 was to head to the Caribbean in what was dubbed “the Western Design”, against Spain. It’s not even the case that Blake went to the Med to counter Spain in its soft under-belly there. Instead, he headed to a small port of Ghar el-Melh (aka Porto Farina) that lies at the northern end of today’s Tunisia and that back then in 1655 was known as a nest of “Barbary” (actually, just Muslim) pirates.

Interestingly, the harbor there had been fortified in decades past by an Ottoman corsair (privateer) called Usta Murad, who had been born an Italian and like several other well-known “Barbary pirates” had converted to Islam. (It’s not known if he did so voluntarily. Anyway, he ran an impressive-looking pirating venture out of Ghar el-Melh for a couple of decades before he died in 1640…)

So here’s the English not-admiral Blake, heading to Ghar el-Melh in early 1655 with his fleet, “in order to pressure the dey Mustafa Laz to free Englishmen held as slaves and to provide compensation for English ships recently seized by local pirates.” Such a noble case. But this WP page on Ghar continues:

The dey offered to provide a new treaty going forward but refused emancipation or compensation for people and ships already taken. Any such action, he felt, should begin with the English, one of whose captains had recently sold a company of Tunisian troops as galley slaves to the Knights of Malta instead of transporting them to Smyrna (present-day Izmir) as arranged. When Blake maintained his blockade, the dey had his warships’ rigging removed, the town’s fortifications strengthened, and its garrison increased. On April 14, 1655, Blake finally attacked. Dividing his fleet to attack the warships and the 20-gun fort simultaneously, he had his men storm and burn the warships in turn before declaring victory and leaving the harbor. Because his sustained assault was able to silence the town’s defenses entirely, the engagement is celebrated as the first successful naval attack on shore-based fortifications.

I think prior to that, naval forces seeking to subdue shore-based fortifications would have had to do so with landing parties that would storm the fortification from land. Now, Blake was opening up new vistas of global conquest for England’s rapidly expanding navy…

Cromwell’s expedition captures Jamaica.

In December 1654, a significant fleet had left left London, in pursuit of Cromwell’s anti-Spanish “Western Design”. The idea was to capture first the Spanish stronghold on Hispaniola (location of today’s Haiti and DR), and then use that as a stepping-stone to attack Spain’s positions everywhere else around the Caribbean and thus seize the sources of much of Spain’s globally-pillaged wealth.

This page on WP tells us how it went:

The expedition left England in December 1654, comprising a fleet of 17 warships and 20 transports, carrying 325 cannons, 1,145 seamen, and 1,830 troops (later reinforced by contingents from other English West Indian colonies to 8,000 strong). Command was jointly held by Admiral William Penn, and Robert Venables, an experienced soldier recently returned from Ireland. The Spanish had been aware of these preparations since July, and ordered improvements to the defences of Hispaniola, correctly assumed to be the main target. The fleet arrived in Barbados at the end of January 1655, and after two months of refitting, sailed for Hispaniola; on 13 April, Penn landed 4,000 men under Venables near Santo Domingo [Hispaniola]. Suffering from dysentery, and harassed by black and mixed-race Spaniards on the march, the expedition failed with the loss of 1,000 men. The English troops evacuated on 25 April.

Even before this, Penn and Venables had barely been on speaking terms, and their relationship now completely broke down. Since they had been given wide discretion, Venables decided to salvage something from the expedition by attacking Jamaica, which was poorly defended. However, having failed to take the main objective of Hispaniola, Penn strongly opposed the attempt, to the extent Venables worried that once disembarked, his men would be abandoned by the fleet.

So, a change of plan. Off they set for Jamaica, led by two grumpy and strongly disagreeing commanders. Given those circumstances, it was notable that they achieved anything. In Jamaica, they were able to take the Spanish governor and his garrison by surprise:

There was an exchange of shots with the Spanish battery covering the inner anchorage, with resistance from a small number of settlers under Francisco de Proenza, a local estate owner, but they soon surrendered.

Penn disembarked the landing force, which quickly occupied Santiago de la Vega, some six miles away. Venables, despite being sick, came ashore on 25 May to dictate terms; the island was annexed by the Commonwealth, and the Spanish inhabitants had to evacuate within a fortnight, on pain of death. After doing what he could to delay the inevitable, [Spanish Governor] Ramírez signed on 27 May; shortly thereafter, he sailed for Campeche, Mexico, but died en route.

Not all the Spanish accepted this; after evacuating noncombatants from northern Jamaica to Cuba, Proenza established his headquarters at the inland town of Guatibacoa. He allied with the Jamaican Maroons based in the mountainous interior, under Juan de Bolas and Juan de Serras, inaugurating a guerrilla war against English occupation.

Penn left for England with half the fleet on 25 June, to ensure his version of why the expedition failed was heard first. He was soon followed by Venables, who arrived in England on 9 September, emaciated and sick; justifying their fears, Cromwell threw them both in the Tower of London. Although released soon after, they were removed from command; Penn was rehabilitated after the 1660 Restoration, but this ended Venables’ career.

The troops left in Jamaica suffered heavily from disease and malnutrition; within a year, only 2,500 remained from the original invasion force of 7,000. Spanish losses were also severe; one of the first victims was de Proenza, who lost his sight, and was succeeded by Cristóbal Arnaldo de Issasi, whose family had been among the original Spanish settlers.

When the English invaded, the Spanish freed their slaves, who fled into the interior, where they established free and independent communities as Maroons. Issasi was appointed Governor in place of Ramirez, and allied with the Maroons, under the leadership of de Bolas and de Serras, tried to frustrate English efforts to establish control over the interior. Spanish attempts to retake Jamaica ended with defeats at Ocho Rios in 1657, and Rio Nuevo in 1658. After this, English Governor Edward D’Oyley persuaded de Bolas to switch sides; without their support, Issasi finally accepted defeat, and fled to Cuba.

Despite continuing their diplomatic efforts to have it returned, Spain eventually ceded the Colony of Jamaica and the Cayman islands in the Treaty of Madrid (1670). Under British rule, the island became a hugely profitable possession, producing large quantities of sugar for export.

Oh yes, sugar.

By the way, the “Maroons” were enslaved Africans who had managed to escape from the plantations and found refuge with the remnants of the island’s indigenous people in its interior, which was wild and mountainous enough to offer them some refuge. This page on the Jamaican Maroons tells us that some of their communities continued to exist and to resist until today.

This is from the page’s summary:

The English, who invaded the island in 1655, expanded the importation of slaves to support their extensive development of sugar-cane plantations. Africans in Jamaica continually fought and revolted, with many who escaped becoming maroons. The revolts had the effect of disrupting the sugar economy in Jamaica and making it less profitable. The revolts simmered down after the British government signed treaties with the Leeward Maroons in 1739 and the Windward Maroons in 1740, which required them to support the institution of slavery. The importance of the Maroons to the colonial authorities declined after slavery was abolished in 1838.

And this tells us about their status today:

To this day, the Maroons in Jamaica are, to a small extent, autonomous and separate from Jamaican culture. Those of Accompong have preserved their land since 1739. The isolation used to their advantage by their ancestors has today resulted in their communities being amongst the most inaccessible on the island.

Today, the four official Maroon towns still in existence in Jamaica are Accompong Town, Moore Town, Charles Town and Scott’s Hall. They hold lands allotted to them in the 1739–1740 treaties with the British. These Maroons still maintain their traditional celebrations and practices, some of which have West African origin. For example, the council of a Maroon settlement is called an Asofo, from the Twi Akan word asafo (assembly, church, society).

Native Jamaicans and island tourists are allowed to attend many of these events. Others considered sacred are held in secret and shrouded in mystery.